South Arts 2020 Southern Prize & State Fellows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Arts Administration Master's Reports Arts Administration Program 12-2015 An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art Grace Rennie University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts Part of the Arts Management Commons Recommended Citation Rennie, Grace, "An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art" (2015). Arts Administration Master's Reports. 185. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts/185 This Master's Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Master's Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Master's Report has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Administration Master's Reports by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Internship Report on the Ogden Museum of Southern Art An Internship Academic Report Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration by Grace Rennie B.F.A. School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2011 December 2015 Table of Contents -

Southeastern Reciprocal Membership Program

SOUTHEASTERN RECIPROCAL MEMBERSHIP PROGRAM Upon presentation of your membership card you will receive: Free admission at all times during museum hours. The same discount in the gift shop and café as those offered to members of that museum. The same discount on purchases made on the premises for concert and lecture tickets, as those offered to members of that museum. Reciprocal privileges do not include receiving mailings from any of the participating museums except for the museum with which the member is affiliated. Note: List subject to change without notice. Museums may temporarily suspend reciprocal program during special exhibitions. Some museums do not accept SERM from other local museums. Call before you go. ALABAMA Augusta Museum of History – Augusta Greensboro Birmingham Museum of Art -- Birmingham Bartow History Museum – Cartersville Greenville Museum of Art – Greenville Carnegie Visual Arts Center -- Decatur Columbus Museum – Columbus Hickory Museum of Art -- Hickory Huntsville Museum of Art – Huntsville Georgia Museum of Art – Athens Mint Museum, Randolph -- Charlotte Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn -- Marietta Museum of History – Marietta Mint Museum Uptown – Charlotte Auburn Morris Museum of Art – Augusta Waterworks Visual Art Center – Salisbury Mobile Museum of Art – Mobile Museum of Arts & Sciences – Macon Weatherspoon Art Museum – Greensboro Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts – Montgomery Museum of Design Atlanta – Atlanta Reynolda House Museum of American Art – Winston Wiregrass Museum of Art – Dothan -

John Alexander

John Alexander 1945 Born in Beaumont, Texas EDUCATION 1970 M.F.A. from Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas 1968 B.F.A. from Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 John Alexander: One World: Two Artists, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA John Alexander: Paintings, J. Johnson Gallery, Jacksonville, FL John Alexander: John Alexander and Walter Anderson, One World: Two Artists, The University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, MS 2010 John Alexander, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX 2009 John Alexander, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2008 John Alexander: Drawings. Hemphill Fine Art, Washington DC John Alexander: A Retrospective. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX John Alexander: New Paintings, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX John Alexander. Drawing Room, East Hampton, NY John Alexander: New Drawings, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX John Alexander: Recent Paintings, Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, CA 2007 John Alexander: New Works on Paper. Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, FL John Alexander: A Retrospective. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC 2006 John Alexander, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2005 John Alexander: The Sea! The Sea!, Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, FL John Alexander: Recent Observations, The Butler Institute of American Art. Youngstown, OH 2004 John Alexander, J. Johnson Gallery, Jacksonville Beach, FL John Alexander, Bentley, Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ 2003 Dishman Gallery of Art, Lamar University, Beaumont, TX JA: 35 Years of Works on Paper. Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, -

HETAG: the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group

HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group HETAG Newsletter No. 31, March 2019 Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art Friday-Sunday, March 29-30, 2019 The 2019 CASETA Symposium and Texas Art Fair at the TCEA Conference Center in Austin, TX. Registration, program and hotel info now available on the CASETA website. Thanks to all who helped make HETAG a Gold sponsor again this year, and to all Houston individual and organization symposium sponsors, including The Menil Collection and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. See you all in Austin in just two weeks! Symposium speakers for 2019: Katherine Brimberry Bradley Sumrall Co-founder and Director Curator of the Collection Flatbed Press and Gallery, Austin, TX Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, Topic: Early Texas Artists in the History LA of the Flatbed Press Topic: The Ogden Museum and Roger Ogden Collections Michael R. Grauer McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture/ Ron Tyler, Ph.D. Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art Former Director, Amon Carter Museum of National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, American Art, Fort Worth, TX Oklahoma City, OK The Art of Texas: 250 Years Porfirio Salinas: Serious Artist or Potboiler Painter Panel – So Much Art, Too Little Space: What can Susie Kalil Collectors Do with Their Artwork? Author/ Independent Curator, Houston, TX and Sue Canterbury Roger Winter The Pauline Gill Sullivan Associate Curator of Artist, New York, NY American Art, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX Fire and Ice: A conversation with artist Roger Winter Ted Lusher Early Texas Art Collector, Austin, TX Liz Kim, Ph.D. -

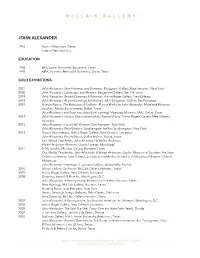

John Alexander

JOHN ALEXANDER 1945 Born in Beaumont, Texas Lives in New York City EDUCATION 1968 BFA, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas 1970 MFA, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 John Alexander: New Paintings and Drawings, Berggruen Gallery, East Hampton, New York 2020 John Alexander: Landscape and Memory, Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco 2018 John Alexander: Recent Drawings & Paintings, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans 2016 John Alexander: Recent Drawings & Paintings, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco 2015 Human/Nature. The Ridiculous & Sublime: Recent Works by John Alexander, Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas John Alexander and Francisco Goya (forthcoming), Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas, Texas 2014 John Alexander: Unique Observations of the Natural World, Arthur Rogers Gallery, New Orleans, Louisiana 2013 John Alexander, Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York John Alexander, Pace Editions, Southampton Art Fair Southampton, New York 2012 Recent Observations, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, Louisiana John Alexander, Pace Editions, Dallas Art Fair, Dallas, Texas One World, Two Artists, John Alexander & Walter Anderson, Walter Anderson Museum, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 2011 In My Garden, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas One World, Two Artists: John Alexander & Walter Anderson, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans University, New Orleans, Louisiana; travelled to University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, Mississippi John Alexander: Paintings, J. Johnson Gallery, Jacksonville, Florida 2010 Life on a Merry-Go-Round, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2009 Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, Louisiana 2008 Drawings, Hemphill Fine Art, Washington, D.C. John Alexander: A Retrospective, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas New Paintings, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas Drawing Room, East Hampton, New York Recent Paintings, Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California New Drawings, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2007 John Alexander, A Retrospective, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. -

2014 Exhibition of Contemporary Southern Art

2014 Exhibition of Contemporary Southern Art Huntsville Museum of Art 2014 Exhibition of Contemporary Southern Art August 17 — October 26, 2014 Major funding is generously provided by: The Kuehlthau Family Foundation With additional support from: The Alabama State Council on the Arts Altherr Howard Design The Women’s Guild of the Huntsville Museum of Art Copyright © 2014 Huntsville Museum of Art All rights reserved Catalogue Design, Illustration & Production: Betty Altherr Howard New Market, AL Photography: The Individual Artists Spike Mafford Seattle, WA Huntsville Museum of Art 300 Church Street Southwest Huntsville, AL 35801 USA 256.535.4350 www.hsvmuseum.org The Red Clay Survey is organized by Peter J. Baldaia, Director of Curatorial Affairs of the Huntsville Museum of Art, to highlight outstanding regional contemporary art. Contents Foreword & Acknowledgments 6 Museum Purchase Awards 7 Juror’s Comments 10 Juror’s Awards 11 The Exhibition 20 Exhibition Checklist 81 Foreword & Acknowledgments The Huntsville Museum of Art is very pleased endeavor. We additionally thank graphic to present the 2014 edition of The Red Clay designer Betty Altherr Howard for providing Survey exhibition of contemporary Southern a handsomely designed exhibition art. Since its inception in 1988, this recurring announcement and catalogue, and for competition has provided a forum for her meticulous management of all aspects current art in our region through a critical of their production. selection of work from eleven Southern states. This year’s Survey features 90 works Public and private support provides the by 72 artists, juried by distinguished artist foundation for this exhibition. We are and educator Susanna Coffey. -

America's Historical and Cultural Organizations

NEH Application Cover Sheet America's Historical and Cultural Organizations PROJECT DIRECTOR Barbara C Batson E-mail:[email protected] Exhibitions Coordinator Phone(W): 804-692-3518 800 East Broad Street Phone(H): Richmond, VA 23219-8000 Fax: UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Arts: History, Criticism, and Theory of the Arts INSTITUTION Library of Virginia Foundation Richmond, VA UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: To Be Sold: Virginia and the American Slave Trade Grant Period: From 4/2014 to 5/2016 Field of Project: History: U.S. History; History: African American History Description of Project: To Be Sold: Virginia and the American Slave Trade is an exploration of the visual and material culture of the American domestic slave trade captured through the paintings and illustrations created by British artist Eyre Crowe based on his 1853 visit to Richmond's slave market. Crowe's works captured the complexities and pathos of American slavery and the internal slave trade. To Be Sold uses Crowe's works as the basis to explore Virginia's role as a mass exporter of enslaved people through the Richmond market to the Lower South and the inner workings of the market itself--the most profitable economic activity in terms of gross receipts in Virginia and possibly the nation. To Be Sold is the first exhibition to explore and examine the development of the visual and material culture of the internal slave trade. The project is comprised of a traveling exhibition (January 2015-March 2016), a one- day, two-site webcast symposium, -

Ogden Museum of Southern Art

OGDEN MUSEUM OF SOUTHERN ART. INC. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF AND FOR THE YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2019 AND 2018 ERICKSEN KRENTEL CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS • CONSULTANTS S Oi Ac 3 - /s. cll OLcl ance witn Lrover IS i ERICKSEN KRENTEL LtKflUbi) PUbLiC ALLOUNIANiS • CaNbULfANTS INDEPENDENT AUDITORS^ REPORT To the Board of Tn^tees of Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Inc. Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Inc. (a nonprofit organization), which comprise the statement of financial position as of December 31, 2019 and 2018, and the related statements of activities, functional expenses, and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management's Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement whether due to fraud or error. Auditors' Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America and the standards applicable to financial audits contained in Government Auditing Standards, issued by the Comptroller General of the United States. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free from material misstatement. -

Manolis Projects Gallery HUNT SLONEM

HUNT SLONEM - Biography Hunt Slonem was born on July 18, 1951 in Kittery, Maine, and his father’s position as a Navy officer meant the family moved often during Hunt’s formative years, including extended stays in Hawaii, California and Connecticut. He would continue to seek out travel opportunities throughout his young-adult years, studying abroad in Nicaragua and Mexico; these eye-opening experiences imbued him with an appreciation for tropical landscapes that would influence his unique style. After graduating with a degree in painting and art history from Tulane University in New Orleans, Slonem spent several years in the early 1970s living in Manhattan. It wasn’t until Janet Fish offered him her studio for the summer of 1975 that Slonem was able to fully immerse himself in his work. His pieces began getting exhibited around New York, propelling his reputation and thrusting him into the city’s explosive contemporary arts scene. He received several prestigious grants, including from Montreal’s Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Cultural Counsel Foundation’s Artist Project, for which he painted an 80-foot mural of the World Trade Center in the late 1970s. He also received an introduction to the Marlborough Gallery, which would represent him for 18 years. As Slonem honed his aesthetic, his work began appearing in unique, contextual spaces. By 1995 he finished a massive six-by-86-foot mural of birds, which shoots across the walls of the Bryant Park Grill Restaurant in New York City. His charity work has resulted dozens of partnerships, including a wallpaper of his famous bunnies designed specifically with Lee Jofa for the Ronald McDonald House in Long Island. -

Larsen Cv Copy

N A T A L I E L A R S E N Exhibions Classrooms Without Borders Exhibi4on, Pi4sburgh, Pennsylvania and Karmiel, Israel, forthcoming 2018/2019 Pi7sburgh Society of Ar4sts Exhibi4on, Spinning Plate Gallery, Pi4sburgh, Pennsylvania, 2015 New AAP Members Exhibi4on, Cultural Trust Educa.on Gallery, Pi4sburgh, Pennsylvania, 2015 Faculty and Alumni Exhibi4on, Marshall University Visual Arts Center, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2014 Maine College of Art Painters 10 Years Later, June Fitzpatrick Gallery, Portland, Maine, 2014 Anonymous Drawings, Galerie Nord/Kunstverein Tiergarten, Berlin, Germany, 2013 24th Naonal Drawing and Print Compe44ve Exhibion, Gormley Gallery, Bal.more, Maryland, 2013 Sense of Place: Sesquicentennial Ar4st Invita4onal, Hun.ngton Museum of Art, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2013 Food: Friend or Foe?, Torpedo Factory’s Target Gallery, Arlington, Virginia, 2013 The Art of Teaching Art, Hun.ngton Museum of Art, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2013 Marshall University Faculty Exhibi4on, Gallery 842, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2012 Gallery Divided, Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences, Charleston, West Virginia, 2012 Cause and Effect, Birke Art Gallery, Marshall University, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2012 Drawing Connecons, Siena Art Ins.tute, Siena, Italy, 2011 Americas 2011: Paperworks, Northwest Art Center, Minot State University, Minot, North Dakota, 2011 Synergis4c, West Tampa Center for the Arts, Tampa, Florida, 2011 On Spirituality: Emerging Visions of the Spiritual, Gallery 842, Hun.ngton, West Virginia, 2011 Body Shots, Joan C. Edwards -

Glyphadelphia Press Release

HESSE FLATOW Glyphadelphia Organized by Carl D’Alvia April 29–May 29 Opening Reception: April 29, 5–8PM by appointment Inquiries: info@hesseflatow.com HESSE FLATOW is pleased to present “Glyphadelphia,” an intergenerational group exhibition organized by sculptor Carl D’Alvia of artists who use different variations of a glyph—ancient hieroglyphics, a question mark, shapes, icons and symbols—as a departure for their work. The exhibition features works by thirty-five artists spanning sculpture, painting, drawing, and collage. The works are loosely grouped into five categories, each representing different definitions of the glyph: the ancient glyph, the body, alphabet and code, geometric and minimalist, and abstracted landscape. Figures in Catherine Haggarty’s work recall Egyptian hieroglyphs of various birds, while Carolyn Salas, Drea Cofield and Amy Pleasant employ repetitive motifs of the human body in their works. Glendalys Medina and Mira Dayal explore the use of abstracted alphabetic characters; Chris Bogia, Matthew Fisher, and Kalina Winters distill compositions down to geometric "Utopian" shapes. Emily Kiacz and Beverly Fishman utilize shaped canvases, inevitably repurposing iconography seen throughout corporate marketing campaigns—and John Dilg’s post-apocalyptic landscape recalls Philip Guston’s glyph-inspired canvases. The glyph has been a subject and inspiration for many artists over the years including Martin Wong, Ray Yoshida, Alina Szapocznikow, Judith Bernstein, Philip Guston, Elizabeth Murray and Deborah Kass. Glyphadelphia—which features artists aged 25 to 76—explores artists’ ongoing interest in using history as a playground, and bridging the gap between ancient and contemporary art. This show presents a catalogue of the different modalities of symbolic communication in use by contemporary artists and how this iconic mode of communication is constantly being adapted in innovative and diverse ways. -

You Can Also View a Digital Version of the Auction Program!

WELCOME Welcome to Cabin Fever, 1708’s 31st Annual—and 1st virtual—Art 1708 GALLERY'S ANNUAL ART AUCTION Auction! We are so incredibly grateful that you are joining us on this most unusual platform in this most unusual time. Thank you for continuing to be a part of Cabin Fever—we feel your love over the internet! We are also full of gratitude for the entire Richmond arts community. Over these past months, you have demonstrated your mettle and heart, CABIN FEVER intrepidness and vision. We are inspired and awed by each of you! And of course, a big THANK YOU to the Cabin Fever artists and the organizers of the Hope Wall project, tonight’s many generous sponsors, 1708’s small but mighty staff, and our fellow Board of Directors. While we can’t come together in person, we can still celebrate contemporary art and artists. The Live and Silent Auctions feature terrific works by regionally and nationally regarded artists. They represent the best emerging talent and the celebrated champions of this city’s art scene. We hope you will log out tonight with an artwork (or two) from this amazing AUCTION COMMITTEE group. These past months we have demonstrated our commitment to being a MOLLY DODGE, PAIGE GOODPASTURE, CATALYST for artists in our community. Through projects like the Space SUSAN JAMIESON, HALEY MCLAREN, Grant program, our new Virtual Studio Tours, and InLight, we found VALERIE MOLNAR, JULIE WEISSEND, creative ways to provide support and outlets for so many emerging talents. AND CAROLINE WRIGHT By purchasing sponsorships, collecting great art, and raising your paddle tonight, YOU are a CATALYST for this transformative support of artists and for the provocative and engaged art that results.