Cross-Race Relationships As Sites of Transformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Police Chief No, Chief Politician Yes the Life of Leon Mercer Jordan, and the Shaping Memories of His Father and Grandfather

1 Police Chief No, Chief Politician Yes The Life of Leon Mercer Jordan, and the Shaping Memories of His Father and Grandfather By Robert M. Farnsworth 2 Dedicated to James C. Olson, whose professional dedication to history led him to complete his biography of Stuart Symington despite years of physical difficulty near the end of his life. His example challenged me in my elder years to tell the story of a remarkable man who made a significant difference in my life. 3 Preface How All This Began I moved from Detroit to Kansas City with my wife and four children in the summer of 1960 to assume my first tenure-track position as an Assistant Professor of American Literature at Kansas City University. The civil rights movement was gathering steam and I had made a couple of financial contributions to the Congress of Racial Equality while still in Detroit. CORE then asked if I were interested in becoming more socially active. I said yes, but I was moving to Kansas City. It took them months to catch up with me again in Kansas City and repeat their question. I again said yes. A few weeks later a field representative was sent to Kansas City to organize those who had showed interest. He called the first meeting in our home. Most who attended were white except for Leon and Orchid Jordan and Larry and Opal Blankinship. Most of us did not know each other, except the Jordans and the Blankinships were well acquainted. The rep insisted we organize and elect officers. -

Pdfblackmillennialmovement V Trump.Pdf

Case 3:20-cv-01464-YY Document 1 Filed 08/26/20 Page 1 of 61 Per A. Ramfjord, OSB No. 934024 [email protected] Jeremy D. Sacks, OSB No. 994262 [email protected] Crystal S. Chase, OSB No. 093104 [email protected] STOEL RIVES LLP 760 SW Ninth Ave, Suite 3000 Portland, OR 97205 Telephone: (503) 224-3380 Kelly K. Simon, OSB No. 154213 [email protected] ACLU FOUNDATION OF OREGON 506 SW 6th Ave, Suite 700 Portland, OR 97204 Telephone: (503) 227-3986 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Mark Pettibone, Fabiym Acuay (a.k.a. Mac Smiff), Andre Miller, Nichol Denison, Maureen Healy, Christopher David, Duston Obermeyer, James McNulty, Black Millennial Movement, and Rose City Justice, Inc. [Additional counsel for Plaintiffs listed on signature page] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF OREGON PORTLAND DIVISION MARK PETTIBONE, an individual; Case No.: 3:20-cv-1464 FABIYM ACUAY (a.k.a., MAC SMIFF), an individual; COMPLAINT ANDRE MILLER, an individual; NICHOL DENISON, an individual; (28 U.S.C. § 1332) MAUREEN HEALY, an individual; CHRISTOPHER DAVID, an individual; DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL DUSTON OBERMEYER, an individual; JAMES MCNULTY, an individual; BLACK MILLENNIAL MOVEMENT, an organization; and ROSE CITY JUSTICE, INC., an Oregon nonprofit corporation, Page 1 - COMPLAINT 107810438.1 0099880-01343 Case 3:20-cv-01464-YY Document 1 Filed 08/26/20 Page 2 of 61 Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity; CHAD F. WOLF, in his individual and official capacity; GABRIEL RUSSELL, in his individual and official capacity; JOHN DOES 1-200, in their individual capacities; UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY; and UNITED STATES MARSHALS SERVICE, Defendants. -

Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: a Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-15-2017 Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters Brandyn-Dior McKinley University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation McKinley, Brandyn-Dior, "Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1665. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1665 Negotiating Motherhood and Intersecting Inequalities: A Qualitative Study of African American Mothers and the Socialization of Adolescent Daughters Brandyn-Dior McKinley, PhD University of Connecticut, 2017 African American middle-class mothers have been understudied in gender and family studies research. To address this gap in the literature, this dissertation uses an intersectional framework to document the raced, classed, and gendered experiences of African American middle-class mothers raising adolescent daughters. Data collected from thirty-six interviews indicated that mothers try to reconcile cultural definitions of motherhood with their present-day social and economic realities. Due to persistent race and class segregation in the United States, mothers and their families spend a considerable amount of time in predominantly white settings. Because mothers do not assume their class status will shield their children from racial bias, mothers engaged in different types of care work to promote their daughters’ educational, emotional, and social development. This included monitoring their daughters’ school environments, helping their daughters develop resistance strategies to combat the effects of discrimination, and constructing culturally affirming support networks. -

A Discourse Analysis of Interruption, Moderator

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF INTERRUPTION, MODERATOR ROLE, AND ADDRESS TERMS IN ARAB AND AMERICAN PANEL NEWS INTERVIEWS BY YOUSEF IBRAHIM AL-ROJAIE Bachelor of Arts King Saud University Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1995 Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2001 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2003 A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF INTERRUPTION, MODERATOR ROLE, AND ADDRESS TERMS IN ARABIC AND AMERICAN PANEL NEWS INTERVIEWS ~ - . ~ ;:Graduate College 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The accomplishment of this dissertation could not have been possible without many people's support and help. I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to all the people who have played significant roles during my Ph.D. studies. First, I am deeply grateful to Dr. Carol Lynn Moder, my mentor and major advisor, not only for her guidance and support of this research, but also for introducing me to discourse analysis upon which much this study b\has been based. Her professional example is a constant source of inspiration. I am also extremely grateful to my wonderful dissertation committee, Dr. Gene Halleck, Dr. Ravi Sheorey, and Dr. Kouider Mokhtari, who all have provided assistance and friendship throughout researching and writing of this work. I would like to take this opportunity to thank my friends for their support, encouragement, and help. Special thanks go to Dr. AbdulAziz al-Ahmad for his enormous efforts with my scholarship. I am also appreciative to other relatives, my father and mother-in law, and my friends, Khalid Abalalkhail and Mansour al-Gefari for their modal support. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

A Linguistic and Conceptual Study of American Public Discourse

Beyond the Issues: A Linguistic and Conceptual Study of American Public Discourse by Pamela Sue Morgan B.A. (University of Tulsa) 1974 B.A. (University of Arizona) 1976 M.A. (University of California, Santa Barbara) 1981 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1993 Ph.D. (University of California, Santa Barbara) 1985 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor George Lakoff, Co-Chair Professor Eve Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor Robin Lakoff Professor David Collier Spring 1998 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Beyond the Issues: A Linguistic and Conceptual Study of American Public Discourse © 1998 by Pamela Sue Morgan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The dissertation of Pamela Sue Morgan is approved: Date 18 /f?8 Co-Chair Date ^ /h^. Date o =oJ2 ^ ^ ' ? £ s' Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 1998 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Beyond the Issues: A Linguistic and Conceptual Study of American Public Discourse by Pamela Sue Morgan Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor George Lakoff, Co-Chair Professor Eve Sweetser, Co-Chair Cultural cognitive models (CCMs) are learned and shared by members of cultural communities and serve as shortcuts to the presentation and understanding of communicative events, including public discourse. They are made up of "frames," here defined as prototypical representations of recurrent cultural experiences or historical references that contain culturally-agreed-upon sets of participants, event scenarios, and evaluations. -

“Pretty Little Liars” TV Series: a Case of Same-Sex Teenage Interactions

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 9, No. 2; 2019 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Sex- and Age-Based Approach to the Study of Interruption in “The Kings of Summer” Movie and “Pretty Little Liars” TV Series: A Case of Same-Sex Teenage Interactions Eman Riyadh Adeeb1 & Amthal Mohammed Abbas2 1 College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Diyala, Diyala, Iraq 2 College of Basic Education, University of Diyala, Diyala, Iraq Correespondence: Eman Riyadh Adeeb, College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Diyala, Diyala, Iraq. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 2, 2019 Accepted: January 30, 2019 Online Published: February 24, 2019 doi:10.5539/ijel.v9n2p229 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v9n2p229 Abstract The study is an attempt to investigate sex and age as crucial factors in the world of interruption. These two factors are investigated theoretically and then practically in two works, “The Kings of Summer” movie and “Pretty Little Liars” TV series. The two works are selected in terms of their compatibility with the core of the study; the characters are teenagers and of the same sex. The study adopts an adapted model to analyze interruption performed by teenagers with special focus on same-sex conversations. The two works’ videos were watched and listened to and then their scripts were precisely examined for more reliable results and judgments. The findings demonstrate that teenagers are characterized by their frequent and numerous interruption. Teenage male speakers are more pleased and relaxed to speak and practice interruption with peers (teenage male speakers). -

Turning Interruptions Into Engagement? a Daily Approach to the Study of Interruptions on the Employee Engagement of Knowledge Workers

TURNING INTERRUPTIONS INTO ENGAGEMENT? A DAILY APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF INTERRUPTIONS ON THE EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT OF KNOWLEDGE WORKERS Shelby Wise A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2019 Committee: Margaret Brooks, Advisor Dena Eber Graduate Faculty Representative Clare Barrett Eric Dubow © 2019 Shelby Wise All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret Brooks, Advisor Workplace interruptions are a job demand that are becoming a reality of work, primarily because of advances in technology and increased connectivity. This is particularly true for knowledge workers who are constantly connected, largely autonomous, and often flexible to work anywhere, anytime. This is concerning as research shows that interruptions negatively influence employee’s satisfaction, performance, and well-being (e.g. Bailey & Konstan, 2006; Eyrolle & Cellier, 2000; Trafton, Altmann, Brock, & Mintz, 2003). However, through the evolution of the Job-Demands Resource Model, it was found that job demands may not be all bad. Demands that are perceived as challenging rather than hindering, motivate employees thus influencing performance and well-being outcomes like employee engagement. The present study examined whether task-based interruptions that have inherently motivating qualities positively affect employee engagement. Additionally, I assessed whether the context (frequency, length, and unexpectedness) of task-based interruptions negatively influence engagement. Results of this study suggested that neither the frequency with which one is interrupted nor the length of time it takes to resolve a task-based interruption influenced engagement. However, the extent to which a task-based interruption was unexpected did negatively relate to engagement in that those that were more unexpected were more detrimental to this construct. -

Tracing Emmett Till's Legacy from Black Lives Matter Back to the Civil

Alicante Journal of English Studies, number 33, 2020, pages 00-00 Alicante Journal of English Studies / Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses ISSN: 0214-4808 | e-ISSN: 2171-861X Special Issue: English Literary Studies Today: From Theory to Activism No. 33, 2020, pages 43-62 https://doi.org/10.14198/raei.2020.33.03 Tracing Emmett Till’s Legacy from Black Lives Matter back to the Civil Rights Movement Martín FERNÁNDEZ FERNÁNDEZ Author: Abstract Martín Fernández Fernández Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain [email protected] This paper explores the legacy of the Emmett Till case as https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5153-5190 one of the core elements which binds together the Civil Date of reception: 30/05/2020 Rights Movement and the current Black Lives Matter in Date of acceptance: 16/10/2020 the US. Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017 Citation: has magnified the escalating racial tension of recent Fernández, Martín. “Tracing Emmet Till’s Legacy from Black Lives Matter back to the Civil Rights years and has, at the same time, fueled several forms Movement.” Alicante Journal of English Studies, no. 33 (2020): 43-62. of social activism across the United States. Acting as https://doi.org/10.14198/raei.2020.33.03 the catalyst for Black Lives Matter, the assassination of © 2020 Martín Fernández Fernández seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012 stirred the race question in the country as the Till lynching had Licence: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License similarly done fifty seven years before. -

HLS 201ES-168 ORIGINAL 2020 First Extraordinary Session HOUSE

HLS 201ES-168 ORIGINAL 2020 First Extraordinary Session HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 21 BY REPRESENTATIVE MARCELLE LEGISLATIVE AFFAIRS: Commends the Black Lives Matter movement 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION 2 To commend the Black Lives Matter movement for its dedication to nonviolent civil action 3 that focuses on systemic racism and gun violence meted out to black people and for 4 shedding light on the issue of racial inequality embedded within the fibers of the 5 United States. 6 WHEREAS, for over four hundred years black people have been fighting for 7 freedom, for their humanity to be recognized, and against slavery, Jim Crow, unjust policing, 8 mass incarceration, and unemployment; and 9 WHEREAS, it makes them the consistent moral compass in a country that was built 10 using various forms of force to require free labor and has thrived on harming the most 11 vulnerable of its population; and 12 WHEREAS, it is important to acknowledge virtuous officers across the United States 13 who hold their counterparts accountable and continuously show acts of sacrifice and 14 heroism; and 15 WHEREAS, the system of policing in the United States that targets black people 16 stems from the history of disparate treatment of black people, including through state laws 17 and other governmental policies that have perpetuated systemic racism; and 18 WHEREAS, repeated instances of police brutality, racial profiling, and excessive use 19 of force have directly caused civil unrest throughout the country and across the globe; and Page 1 of 4 HLS 201ES-168 -

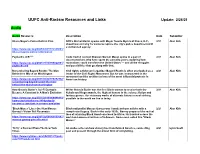

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

A Conversation Analysis of Interruption in High School Musical Movie Series

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lumbung Pustaka UNY (UNY Repository) A CONVERSATION ANALYSIS OF INTERRUPTION IN HIGH SCHOOL MUSICAL MOVIE SERIES A THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Attainment of a Sarjana Sastra Degree in English Language and Literature By Ana Shofia Amalia 10211141037 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE STUDY PROGRAM ENGLISH EDUCATION DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS YOGYAKARTA STATE UNIVERSITY 2016 MOTTOS “…And whoever fears Allah and keeps his duty to Him, He will make a way for him to get out (from every difficulty).” -Q.S. At-Talaq (65): 2- An arrow can only be shot by pulling it backward. So when life is dragging you back with difficulties, it means that it’s going to launch you into something great. So just focus, and keep aiming! -Anonymous- If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward. -Martin Luther King Jr.- Miracle is another name for hard work -Kang Tae Joon, To the Beautiful You- Success is not the key to happiness. But happiness is the key to success. If you love what you are doing, you will be successful. -Albert Schweitzer- v DEDICATIONS This thesis is specially dedicated to: My Beloved Parents and My Dearest Brother vi TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE...................................................................................................................... i APPROVAL SHEET ............................................................................................