Copway and Traill in a Conversation That Never Took Place Daniel Coleman Mcmaster University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State:Alabama ---Incomelimit S

STATE:ALABAMA ---------------------------INCOMELIMITS---------------------------- PROGRAM 1 PERSON 2 PERSON 3 PERSON 4 PERSON 5 PERSON 6 PERSON 7 PERSON 8 PERSON Anniston-Oxford, AL MSA FY 2013 MFI: 53100 30% OF MEDIAN 11200 12800 14400 15950 17250 18550 19800 21100 VERY LOW INCOME 18600 21250 23900 26550 28700 30800 32950 35050 LOW-INCOME 29750 34000 38250 42500 45900 49300 52700 56100 Auburn-Opelika, AL MSA FY 2013 MFI: 63000 30% OF MEDIAN 13250 15150 17050 18900 20450 21950 23450 24950 VERY LOW INCOME 22050 25200 28350 31500 34050 36550 39100 41600 LOW-INCOME 35300 40350 45400 50400 54450 58500 62500 66550 Birmingham-Hoover, AL MSA Birmingham-Hoover, AL HMFA FY 2013 MFI: 57100 30% OF MEDIAN 12550 14350 16150 17900 19350 20800 22200 23650 VERY LOW INCOME 20900 23900 26900 29850 32250 34650 37050 39450 LOW-INCOME 33450 38200 43000 47750 51600 55400 59250 63050 Chilton County, AL HMFA FY 2013 MFI: 52000 30% OF MEDIAN 10950 12500 14050 15600 16850 18100 19350 20600 VERY LOW INCOME 18200 20800 23400 26000 28100 30200 32250 34350 LOW-INCOME 29150 33300 37450 41600 44950 48300 51600 54950 Walker County, AL HMFA FY 2013 MFI: 41400 30% OF MEDIAN 9750 11150 12550 13900 15050 16150 17250 18350 VERY LOW INCOME 16250 18550 20850 23150 25050 26900 28750 30600 LOW-INCOME 25950 29650 33350 37050 40050 43000 45950 48950 Columbus, GA-AL MSA FY 2013 MFI: 48200 30% OF MEDIAN 10450 11950 13450 14900 16100 17300 18500 19700 VERY LOW INCOME 17400 19900 22400 24850 26850 28850 30850 32850 LOW-INCOME 27900 31850 35850 39800 43000 46200 49400 52550 Decatur, -

Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes

Zawadzka Temagami Area Rock Art 159 Beyond the Sacred: Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes Dagmara Zawadzka The rock art of the Temagami area in northeastern Ontario represents one of the largest concentrations of this form of visual expression on the Canadian Shield. Created by Algonquian-speaking peoples, it is an inextricable part of their cultural landscape. An analysis of the distribution of 40 pictograph sites in relation to traditional routes known as nastawgan has revealed that an overwhelming majority are located on these routes, as well as near narrows, portages, or route intersections. Their location seems to point to their role in the navigation of the landscape. It is argued that rock art acted as a wayfinding landmark; as a marker of places linked to travel rituals; and, ultimately, as a sign of human occupation in the landscape. The tangible and intangible resources within which rock art is steeped demonstrate the relationships that exist among people, places, and the cultural landscape, and they point to the importance of this form of visual expression. Introduction interaction in the landscape. It may have served as The boreal forests of the Canadian Shield are a boundary, resource, or pathway marker. interspersed with places where pictographs have Therefore, it may have conveyed information that been painted with red ochre. Pictographs, located transcends the religious dimension of rock art and most often on vertical cliffs along lakes and rivers, of the landscape. are attributed to Algonquian-speaking peoples and This paper discusses the rock art of the attest, along with petroglyphs, petroforms, and Temagami area in northeastern Ontario in relation lichen glyphs, to a tradition that is at least 2000 to the traditional pathways of the area known as years old (Aubert et al. -

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers Family Fonds 2Nd Acc. 1992-13 10 Cm

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers family fonds 2nd acc. 1992-13 10 cm. Finding aid Prepared by Linda Hoad August 1992 Box 1 Correspondence 1. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1835 Jan. 29 2. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] J.W.D. Moodie 1835 April 6 3. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1847 Nov. 25 4. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1832 June 14 5. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1834 Feb. 25 [incomplete] 6. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1835 May 17 [incomplete] 7. Goldschm[idt], D.L. Mrs. Mason 1885 Dec. 19 re: her daughter Sarah, his servant 8. McColl, Evan J.W.D. Moodie 1869 15 April 9. McLachlan, Alexander, Susanna Moodie 1861 Aug. 26 1818-1896 10. McLachlan, Alexander, J.W.D. Moodie 1866 9 Dec. 1818-1896 11. Moodie, Donald J.W.D. Moodie 1830 July 10 12. Moodie, J.W.D. Susanna Moodie 1839 5th July 12a. Moodie, Susanna Ethel Vickers 1882 4 March [removed from the back of watercolour of moths to which the letter refers] 13. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 Jan. 17 1789-1834 14. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 March 6 1789-1834 Manuscripts Moodie, J.W.D. Lectures by J.W. D. Moodie: "Water and its distribution over the surface of the Earth," n.d., 14 leaves "The Norsemen and their conquests and adventures," n.d., 11 leaves Box 2 Moodie, J.W.D. Music album. [ca 1840?] Some tunes copied, some original compositions. Several tunes dated: 1840, 1842. Box 3 Moodie, J.W.D. -

Canadian Crusoes by Catherine Parr Traill</H1>

Canadian Crusoes by Catherine Parr Traill Canadian Crusoes by Catherine Parr Traill Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Widger, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team CANADIAN CRUSOES. A Tale of THE RICE LAKE PLAINS. CATHARINE PARR TRAIL, AUTHORESS OF "THE BACKWOODS OF CANADA, ETC." EDITED BY AGNES STRICKLAND. page 1 / 293 ILLUSTRATED BY HARVEY. LONDON: ARTHUR HALL, VIRTUE, & CO. 25, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1852. DEDICATED TO THE CHILDREN OF THE SETTLERS ON THE RICE LAKE PLAINS, BY THEIR FAITHFUL FRIEND AND WELL-WISHER THE AUTHORESS. page 2 / 293 OAKLANDS, RICE LAKE, 15_th Oct_ 1850 PREFACE IT will be acknowledged that human sympathy irresistibly responds to any narrative, founded on truth, which graphically describes the struggles of isolated human beings to obtain the aliments of life. The distinctions of pride and rank sink into nought, when the mind is engaged in the contemplation of the inevitable consequences of the assaults of the gaunt enemies, cold and hunger. Accidental circumstances have usually given sufficient experience of their pangs, even to the most fortunate, to make them own a fellow-feeling with those whom the chances of shipwreck, war, wandering, or revolutions have cut off from home and hearth, and the requisite supplies; not only from the thousand artificial comforts which civilized society classes among the necessaries of life, but actually from a sufficiency of "daily bread." Where is the man, woman, or child who has not sympathized with the poor seaman before the mast, Alexander Selkirk, typified by the genius -

Rock Art Studies: a Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17 Keywords: Peterborough, Canada. North America. Cultural Adams, Amanda Shea resource management. Conservation and preservation. 2003 Reprinted from "Measurement in Physical Geography", Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Occasional Paper No. 3, Dept. of Geography, Trent Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, BCMaster/s Thesis :79 pgs, University, 1974. Weathering. University of British Columbia. Cited from: LMRAA, WELLM, BCSRA. Keywords: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. North America. Stylistic analysis. Marpole Culture. Vision. Alberta Recreation and Parks Abstract: "This study explores the stylistic variability and n.d. underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Writing-On-Stone Provincial ParkTourist Brochure, Alberta Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in Recreation and Parks. the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of Keywords: WRITING-ON-STONE PROVINCIAL PARK, ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical ALBERTA, CANADA. North America. "THE BATTLE and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock SCENE" PETROGLYPH SITE INSERT INCLUDED WITH art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise PAMPHLET. proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short Cited from: RCSL. period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the Allen, W.A. imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations 2007 (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 2, No. 5; November 2015 Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity Carla Comellini Associate Professor English Literature, Director of the Canadian Centre "Alfredo Rizzardi" University of Bologna Via Cartoleria 5, Bologna Notwithstanding the linguistic and cultural differences between the English and French areas, Canadian Literature can be defined as a whole. This shared umbrella, called Canada, creates an image of mutual correspondence that can be metaphorically expressed in culinary terms if one likes to use the definition ironically adopted by J.K. Keefer: “the roast beef of old England and the champagne of la douce Franc,” (“The East is Read”, p.141) This Canadian umbrella is also made up of other linguistic and cultural varieties: from those of the First Nation People to those imported by the immigrants. It is because of the mutual correspondence that Canadian literature is imbued with the constant metaphorical interplay between ‘nature’ and the ‘story teller’, between the individual story and the collective history, between the personal memory and the collective one. Among the immigrants, there are some Italian poets and writers who had immigrated to Canada becoming naturalized Canadians. Without mentioning all the immigrants/writers, it is worth remembering Michael Ondaatje, who was born in Sri Lanka. It is not so out of place that Ondaatje uses an Italian immigrant, David Caravaggio, as a character for both novels: In the Skin of a Lion (1988) and The English Patient (1992). David Caravaggio represents the image of the split personality of any immigrant as his name brilliantly explains: Ondaatje’s Italian Canadian character is no more Davide (the Italian Christian Name) because it had been anglicized in David. -

Susanna Moodie and the English Sketch

SUSANNA MOODIE AND THE ENGLISH SKETCH Carl Ballstadt S,USANNA MOODIE's Roughing It in the Bush has long been recognized as a significant and valuable account of pioneer life in Upper Canada in the mid-nineteenth century. From among a host of journals, diaries, and travelogues, it is surely safe to say, her book is the one most often quoted when the historian, literary or social, needs commentary on backwoods people, frontier living conditions, or the difficulty of adjustment experienced by such upper middle-class immigrants as Mrs. Moodie and her husband. The reasons for the pre-eminence of Roughing It in the Bush have also long been recognized. Mrs. Moodie's lively and humorous style, the vividness and dramatic quality of her characterization, the strength and good humour of her own personality as she encountered people and events have contributed to make her book a very readable one. For these reasons it enjoys a prominent position in any survey of our literary history, and, indeed, it has become a "touchstone" of our literary development. W. H. Magee, for example, uses Roughing It in the Bush as the prototype of local colour fiction against which to measure the degree of success of later Canadian local colourists.1 More recently, Carl F. Klinck ob- serves that Mrs. Moodie's book represents a significant advance in the develop- ment of our literature from "statistical accounts and running narratives" toward novels and romances of pioneer experience.2 Professor Klinck, in noting the fictive aspects of Mrs. Moodie's writing, sees it as part of an inevitable, indigenous de- velopment of Canadian writing, even though, in Mrs. -

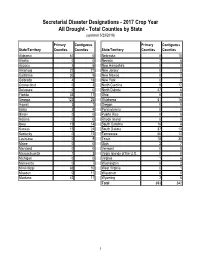

2017 Crop Year Secretarial Disaster Designations

Secretarial Disaster Designations - 2017 Crop Year All Drought - Total Counties by State (updated 5/23/2018) Primary Contiguous Primary Contiguous State/Territory Counties Counties State/Territory Counties Counties Alabama 67 0 Nebraska 0 10 Alaska 0 0 Nevada 2 6 Arizona 5 6 New Hampshire 0 0 Arkansas 22 21 New Jersey 0 0 California 35 9 New Mexico 0 2 Colorado 4 18 New York 0 0 Connecticut 0 3 North Carolina 9 12 Delaware 0 0 North Dakota 47 6 Florida 35 17 Ohio 0 0 Georgia 122 25 Oklahoma 51 16 Hawaii 3 1 Oregon 0 0 Idaho 3 4 Pennsylvania 0 0 Illinois 0 0 Puerto Rico 0 0 Indiana 0 0 Rhode Island 0 0 Iowa 19 14 South Carolina 16 6 Kansas 15 24 South Dakota 37 13 Kentucky 0 12 Tennessee 66 14 Louisiana 0 9 Texas 18 30 Maine 0 0 Utah 2 7 Maryland 0 0 Vermont 0 0 Massachusetts 1 3 Virgin Islands of the U.S. 0 0 Michigan 0 0 Virginia 1 6 Minnesota 0 7 Washington 0 2 Mississippi 69 10 West Virginia 0 1 Missouri 0 11 Wisconsin 0 0 Montana 42 11 Wyoming 2 6 Total 693 342 1 2017 All Drought - Primary and Contiguous Counties (updated 5/23/2018) State/Territory Primary County St/Co FIPS Code Alabama Autauga 01001 Alabama Baldwin 01003 Alabama Barbour 01005 Alabama Bibb 01007 Alabama Blount 01009 Alabama Bullock 01011 Alabama Butler 01013 Alabama Calhoun 01015 Alabama Chambers 01017 Alabama Cherokee 01019 Alabama Chilton 01021 Alabama Choctaw 01023 Alabama Clarke 01025 Alabama Clay 01027 Alabama Cleburne 01029 Alabama Coffee 01031 Alabama Colbert 01033 Alabama Conecuh 01035 Alabama Coosa 01037 Alabama Covington 01039 Alabama Crenshaw 01041 Alabama -

The Journals of Susanna Moodie1

History of Intellectual Culture www.ucalgary.ca/hic/ · ISSN 1492-7810 2001 Haunted: The Journals of Susanna Moodie1 Jennifer Aldred Abstract Using an interpretive, hermeneutical approach, this article explores the work of Susanna Moodie, Margaret Atwood, and Charles Pachter. The intertextual resonances that connect these works are examined, as well as the link between text, image, and visuality. Susanna Moodie was a nineteenth century British immigrant to the backwoods of Canada, and her autobiographical text provides a narrative context from which both Margaret Atwood and Charles Pachter respectively grapple with and negotiate the complex, polyglossic nature of Canadian culture, identity, and art. The interface between Atwood’s poetic explication of cultural, linguistic, and literary identity and Pachter’s illustrative visual representations reveals the powerful synergy that is born when text and image collide. We are all immigrants to this place even if we were born here: the country is too big for anyone to inhabit completely, and in the parts unknown to us we move in fear, exiles and invaders. This country is something that must be chosen—it is so easy to leave—and if we do choose it we are still choosing a violent duality. Atwood, The Journals of Susanna Moodie Despite my intentions of discussing Charles Pachter’s visual rendition of Margaret Atwood’s The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970), I found it impossible to extricate this marriage of interpretive artwork and poetry from its long lineage of intertexts. I was reminded, yet again, that as readers, viewers, and interpreters, we loop and spiral our way towards what we think is the coherent, textured “ending”—the “fi nal word” in an ancestry of narratives—only to fi nd that intertextuality has indeed unsettled discursive chronology, and middles and endings have blurred into polyglossic beginnings. -

Primary Sources

Archived Content This archived Web content remains online for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It will not be altered or updated. Web content that is archived on the Internet is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats of this content on the Contact Us page. Roughing It in the Backwoods Student Handout Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill are two of Canada’s most important 19th-century writers. Born in England, the two sisters became professional writers before they were married. In 1832, they emigrated with their Scottish husbands to Canada and settled in the backwoods of what is now Ontario, near present-day Lakefield. Their experiences as pioneers gave them much to write about, which they did in their books, articles, poems and letters to family members. This activity will give you the chance to view primary source materials online and learn about aspects of life as an early settler in the backwoods of Upper Canada. Introduction: Primary Sources A primary source is a first-hand account, by someone who participated in or witnessed an event. These sources could be: letters, books written by witnesses, diaries and journals, reports, government documents, photographs, art, maps, video footage, sound recordings, oral histories, clothing, tools, weapons, buildings and other clues in the surroundings. A secondary source is a representation of an event. It is someone's interpretation of information found in primary sources. These sources include books and textbooks, and are the best place to begin research. -

Number of Medicare FFS Emergency Transport Claims by State and County Or Equivalent Entity, 2017

Number of Medicare FFS Emergency Transport Claims by State, 2017 STATE/TERRITORY CLAIM COUNT ALABAMA 171,482 ALASKA 14,631 ARIZONA 140,516 ARKANSAS 122,909 CALIFORNIA 788,350 COLORADO 105,617 CONNECTICUT 152,831 DELAWARE 47,239 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA 25,593 FLORIDA 637,127 GEORGIA 289,687 GUAM 2,338 HAWAII 19,028 IDAHO 35,581 ILLINOIS 419,315 INDIANA 229,877 IOWA 104,965 KANSAS 92,760 KENTUCKY 184,636 LOUISIANA 163,083 MAINE 72,731 MARYLAND 194,231 MASSACHUSETTS 318,382 MICHIGAN 327,029 MINNESOTA 146,030 MISSISSIPPI 141,840 MISSOURI 222,075 MONTANA 26,943 NEBRASKA 49,449 NEVADA 75,571 NEW HAMPSHIRE 57,423 NEW JERSEY 315,471 NEW MEXICO 55,554 NEW YORK 493,291 NORTH CAROLINA 418,959 NORTH DAKOTA 21,502 NORTHERN MARIANAS 826 STATE/TERRITORY CLAIM COUNT OHIO 390,605 OKLAHOMA 150,046 OREGON 98,867 PENNSYLVANIA 391,482 PUERTO RICO 7,769 RHODE ISLAND 40,743 SOUTH CAROLINA 219,186 SOUTH DAKOTA 26,748 TENNESSEE 237,657 TEXAS 629,151 UTAH 32,309 VERMONT 29,689 VIRGIN ISLANDS 1,577 VIRGINIA 271,194 WASHINGTON 179,466 WEST VIRGINIA 93,968 WISCONSIN 158,239 WYOMING 17,357 Number of Medicare FFS Emergency Transport Claims by State and County or Equivalent Entity, 2017 STATE/TERRITORY COUNTY/EQUIVALENT CLAIM COUNT ALABAMA Autauga 1,326 ALABAMA Baldwin 7,050 ALABAMA Barbour 1,256 ALABAMA Bibb 429 ALABAMA Blount 1,372 ALABAMA Bullock 246 ALABAMA Butler 1,058 ALABAMA Calhoun 5,975 ALABAMA Chambers 1,811 ALABAMA Cherokee 885 ALABAMA Chilton 1,298 ALABAMA Choctaw 777 ALABAMA Clarke 980 ALABAMA Clay 491 ALABAMA Cleburne 628 ALABAMA Coffee 1,941 ALABAMA Colbert -

Recording the Reindeer Lake

CONTEXTUALIZING THE REINDEER LAKE ROCK ART A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Perry Blomquist © Copyright Perry Blomquist, April 2011. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5B1 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT The rock art that is found in the region of Reindeer Lake, Saskatchewan is part of a larger category of rock art known as the Shield Rock Art Tradition.