Ilani Wilken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDIT Dress Code 20-21 Updated 21 Jan 2021

Online Stores: Dennis Uniforms (Uniform Store) BIS Houston Spirit Store (PE Uniforms and Spirit Wear) Bulldogs Online Store (Team Athletics Wear, Custom BISH Items, Custom Spirit Wear and cold weather PE.) BISH Dress Code Why do we have a dress code? At the British International School of Houston, we believe that our dress code helps us in creating a school identity, developing our school community, and promoting our school’s core values: Pride, Unity, and Respect. Pride: Wearing the Nord Anglia logo or the BISH Bulldog develops pride in being a member of our school community. When out of school on trips, it provides our students with an easily recognizable identity. Additionally, it invites students to take pride in their appearance. Unity: Provides a sense of community and unity among same-age peers. Respect: Reduces the possibility of social conflict associated with appearance and increases students’ respect for each other’s character and abilities. Learning: As learning is at the center of all we do at BISH, our dress code is similarly aligned. Anything that distracts oneself or others from learning is not permitted. Why do we have Spirit Day? Spirit Day takes place every Friday and is an extension of our regular dress code. On Spirit Days we celebrate different aspects of our community by wearing school Spirit wear. Spirit Day aims to bring together our students of all ages and unites the school through our “Bulldog Pride”. Where do I purchase my child’s school wear? Items with the British International School of Houston logo can be purchased from Dennis Uniform, located at: 2687 Wilcrest Drive #L07, Houston, TX 77042, phone (713) 789-0932 or online at: https://www.dennisuniform.com. -

Men's Formalwear: Innovation

Continuous Development GM Product Knowledge Men’s Formalwear: Innovation retail What is formal wear? Paul, an M&S technologist, explains why Innovation is so important A Customer asks you the in Men’s Formalwear… following… find Every man should own at least one suit, a shirt and a tie (or equivalent garment) in a suitable option accordance with his heritage. They should be pressed, clean, and ready to go at a in your formal moment’s notice. shirt range: A formal working wardrobe needs to work with the customers lifestyle. Ideally a suit and the ‘I need a shirt that I can put in accompanying garments should look and feel as good at the end of the day as they did at my overnight bag and pull out the beginning. This is why we are always reviewing our formalwear package to make it an and wear the next day’ easy to wear, hassle free and comfortable purchase. ‘My shirt has visible sweat stains Starting with Shirts at the end of the working day, Sharon, a Customer Assistant on men’s formalwear at what can you recommend?’ Milton Keynes, asks about Stain Release formal shirts, Paul explains…Using the example of a white shirt, it looks great, but will pick up a lot of grime in a normal working day. We apply a fabric Grab your finish on key areas like the collars and the cuffs, which resist spills SSPR, Which & releases stains. We then test to M&S standards by treating 12 different stains as per formal shirt is wash instructions. -

BISH Dress Code 2018/2019

BISH Dress Code 2018/2019 BISH Dress Code Why do we have a dress code? At the British International School of Houston, we believe that our dress code helps us in creating a school identity, developing our school community, and promoting our school’s core values: Pride, Unity, and Respect. Pride: Wearing the Nord Anglia logo or the BISH Bulldog develops pride in being a member of our school community. When out of school, on trips, it provides our students with an easily recognizable identity. Additionally, it invites students to take pride in their appearance. Unity: Provides a sense of community and unity among same-age peers. Respect: Reduces the possibility of social conflict associated with appearance and increases students’ respect for each other’s character and abilities. Why do we have Spirit Day? Spirit Day takes place every Friday and is an extension of our regular dress code. On Spirit Days we celebrate different aspects of our community by wearing school Spirit wear. Spirit Day aims to bring together our students of all ages and unites the school through our “Bulldog Pride”. Where do I purchase my child’s school wear? Items with the British International School of Houston logo can be purchased from Dennis Uniform, located at - 2687 Wilcrest Drive #L07, Houston, TX 77042, phone (713) 789-0932 or online at: https://www.dennisuniform.com. PE wear, school hats, and approved school outer wear (sweatshirts or quarter zips-ups), with the School’s logo on, can be purchased from the School’s Spirit Store. Early Years 0 to Early Years -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Post-16 Appearance and Dress Code This Policy Has Been Adapted from the GEMS Staff Appearance and Dress Code Policy

Post-16 Appearance and Dress Code This policy has been adapted from the GEMS staff appearance and dress code policy. As Post-16 students, the expectation is that you look and dress like young professionals. Male Students: Smart formal trousers or chinos (no jeans, cords, or combat style trousers.) Smart formal shirt and tie (the top button must be fastened on the shirt.) A smart formal jumper or jacket/blazer may be worn over shirt. T-shirts, polos, and hoodies are not permitted. Clean formal shoes (no trainers, sneakers, sandals, or flipflops.) Colours and patterns are permitted. Clean shaven or trimmed moustache and/or beard.) Male Students Active Wear: Must only be worn during active sessions. Shorts must not be too short. Muscle t-shirts and tank tops are not permitted. Sneakers or trainers must be worn – not other footwear is accepted. Female Students: Required to dress in a way that is respectful to the Muslim society in which we live. Smart skirt (skirt should neither be too tight or too short – knee length is expected.) Smart trousers (no jeans, cords, leggings or combat style trousers.) Trousers must not be tight fitting. Sleeveless blouses are not permitted (shoulders must be covered.) Low-cut blouses are not acceptable. Blouses must not be made of see through material. T-shirts and hoodies are not permitted. A smart formal jumper or jacket/blazer may be worn A smart, business like dress (must follow the skirt and blouse outlines above.) Clean formal shoes (no trainers, sneakers, sandals, or flipflops.) Smart open (heel OR toe) shoes are acceptable. -

Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instructions

National A-DH-265-000/AG-001 Defence CANADIAN ARMED FORCES DRESS INSTRUCTIONS (English) (Supersedes A-AD-265-000/AG-001 dated 2017-02-01) Issued on Authority of the Chief of the Defence Staff OPI: DHH 2017-12-15 A-DH 265-000/AG-001 FOREWORD 1. A-DH-265-000/AG-001, Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instructions, is issued on authority of the Chief of Defence Staff. 2. The short title for this publication shall be CAF Dress Instructions. 3. A-DH-265-000/AG-001 is effective upon receipt and supersedes all dress policy and rules previously issued as a manual, supplement, order, or instruction, except: a. QR&O Chapter 17 – Dress and Appearance; b. QR&O Chapter 18 – Honours; c. CFAO 17-1, Safety and protective equipment- Motorcycles, Motor scooters, Mopeds, Bicycles and Snowmobiles; and 4. Suggestions for revision shall be forwarded through the chain of command to the Chief of the Defence Staff, Attention: Director History and Heritage. See Chapter 1. i A-DH 265-000/AG-001 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................... i CHAPTER 1 COMMAND, CONTROL AND STAFF DUTIES ............................................................. 1-1 COMMAND ...................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 CONTROL ..................................................................................................................................................... -

CREW-UNIFORMS.Pdf

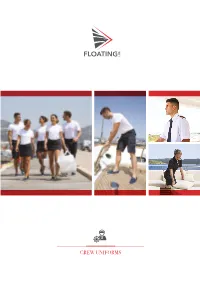

CREW UNIFORMS CREW UNIFORMS EVOLUTION WEAR - CASUAL WEAR FORMAL WEAR - JACKETS - WORK WEAR ACCESSORIES & SHOES - CUSTOM WEAR Floating Life Crew Uniforms are a choice of style. A drawing and design consultancy service, together with A style that takes centre stage right down to the tiniest our talented and professional collaborators, is available detail. Inspired by the great tradition of Italian fashion, upon request. Floating Life has defined a new standard for the yachting We can tailor-made outfits to suit any requirement be it world with the creation of an exclusive line of Crew colour, logo, fabric and other specific needs. Uniforms. A high-end, perfectly cut, Collection with a We pride ourselves of an honest and personalized service tailored look, made with fabrics of the utmost quality by meeting with customers and delivering up to the Yachts. that places emphasis on the comfort and wearability that It goes without saying that we provide after-sale service are essential for workwear, all whilst highlighting the and winter storage facilities. accuracy of its design. Our Collections are tailored to wide-ranging usages, be it Our garments are continuous and all “Made in Italy”, in Evolution, Casual, Formal, Jackets, Work or Custom. line with our idea of high-quality clothing and designed For added flare, style-up your Crew Uniform with a piece specifically for crews, tested by them and improved every from our Crew Accessories range: foulards, ties, epaulets, year to be the best and most practical Uniforms they can belts, caps and shoes. have. Our true versatility can also be seen in our evening range and its unique customer designs, suitable for themed and high glamour events. -

Fall 2020 Look Book Dear Friends

Fall 2020 Look Book Dear Friends, We are going through a unique period in history, not only for us as Canadians but for humanity. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted each one of us, changed how we live, how we behave and how we interact with each other. Yet, what has been encouraging through this time, is how so many Canadians have stepped up and volunteered to help those in need. It epitomizes what being a Canadian is all about. Here at KING & BAY, we too experienced the generosity of our fellow Canadians. Our clients stepped up by donating over 700 shirts to our SOYB Facemask Challenge. Meanwhile, our sta at KING & BAY along with a team of community sewers produced and donated over 15,000 facemasks to those in need. We are so grateful to our clients and colleagues for doing their part in supporting Canadians and being exemplary citizens. As we move into the Fall, and days more promising, we are pleased to share our new collection for Fall 2020. The aim of the collection is to inspire optimism in the future, to transport us beyond the confines of the pandemic to a time when life is less complicated. As you look through our collection please know that we have taken all the necessary precautions, following all government COVID-19 protocols, to create a safe space for you to visit us in our private lounge. Alternatively, if you feel more inclined to shop from the convenience of your home, we would like to introduce to you our Virtual Style portal which allows you to have a virtual consultation with one of our Master Clothiers. -

Power Dressing for Women Basic1.Pdf

First Impressions 90% of our impressions are formed within the first 20-30 seconds on meeting a stranger: • 60% of our impressions are based on how we look • 40% on how we sound and & what we say POWER DRESSING for WOMEN TRADITIONAL OR WESTERN? Whichever style you opt for, the keywords are comfort and style.. Work clothes for women • From sarees to salwar kameezes • From westerns to Indo- westerns. Salwar Kameez: • Comfort to carry • Carry it with élan • Short kurtas, styled with trouser-like pajamas, look chic and very Indian. Stoles and short scarves have replaced difficult-to-manage dupattas • Long Tunic like Kurtas are being teamed with pants as well. Body Silhouettes • Wear loose fitting clothes to complement your body shape • Dark colours help look slimmer • Cuts should be classy INDO-WESTERN • Flat-front trousers • ¾th length tops • Cotton-linen shirts in bright colours • Multiple-function jackets & suits • Long wrap-around skirts are among the many options here. Western Wear: • Vibrant Look • Jackets fitting to body contours • Detailed with crystal buttons • Slick necklines • Knee-length skirt • Corporate colours: grey, black, navy, brown and white • Comfortable shoes in soft leather and neutral colours Trouser length should be one and a half inches from the floor to the back of the heel. Buttons, belts and fly of the trouser should be neatly aligned. Opt for Cotton-Lycra and Linen-Lycra as trousers maintain their crease and fall Business casuals Sleeveless is unacceptable. It's either a formal collared shirt teamed with a pair of formal trousers or a skirt (never jeans). -

Clubclass 4.22 MB Download

Europe’s finest collection ...More than a Uniform of business wear for work Six versatile tailored collections perfect for just about any job. Each collection, in it's own way, offers specific functions that suits various wearers and help express their character and your business to project a professional modern image. Contents 8 ENVEE COLLECTION 76 ENDURANCE P.V COLLECTION “The Freedom Of Movement.” The Endurance P.V. Collection “Simply The most advanced ultra stretch tailoring Made To Perform At Work”. Extreme available for work. Engineered using an performance like Endurance but at a ultra tech stretch Poly/Visc/Lycra that more competitive price. The Endurance stretches in all directions for maximum P.V. Collection is the best performing comfort at work. Stylish, comfortable and collection of business tailored clothing performs. Enjoy wearing Envee to work you can buy at this price level. everyday. Worth paying a little more for the best tailoring for work today. 32 EVOLUTION COLLECTION 88 ENDURANCE COLLECTION The Evolution Collection is tailored from a The Endurance Collection is made from mid weight Poly/Wool/Lycra fabric. Used fine wool mixed with branded low pil in our collections for more than 10 years polyester to give the ultimate garment this is a truly tried and tested collection performace. At Clubclass when we of Corporate Clothing. use the word Performance we mean it. Too many Corporate Clothing providers Some of Europe’s largest companies wear believe merely adding the word the Evolution Collection. From the front performance to their label makes for of house desk at London’s best hotels a viable performance tailored clothing to a number of high profile transport solution. -

Uniform Collection 2018

UNIFORM COLLECTION 2018 www.floatinglife.com CREW UNIFORMS CASUAL - EVOLUTION - FORMAL TECHNICAL - WORK - CUSTOM ACCESSORIES & SHOES Floating Life Crew Uniforms are a choice of style. A style that A drawing and design consultancy service, together with our takes centre stage right down to the tiniest detail. Inspired by talented and professional collaborators, is available upon the great tradition of Italian fashion, Floating Life has defined request. We can tailor-made outfits to suit any requirement a new standard for the yachting world with the creation of an be it colour, logo, fabric and other specific needs. We pride exclusive line of Crew Uniforms. ourselves of an honest and personalized relationships by A high-end, perfectly cut, collection with a tailored look, made meeting with customers and delivering up to the Yachts. with fabrics of the utmost quality that places emphasis on It goes without saying that we provide after-sale service and the comfort and wearability that are essential for workwear, winter storage facilities. all whilst highlighting the accuracy of its design. Our collections are tailored to wide-ranging usages, be it Our garments are continuous and all “made in Italy”, in line Casual, Evolution, Formal, Technical, Work or Custom. with our idea of high-quality clothing and designed specifically For added flare, style-up your Crew Uniforms with a piece for crews, tested by them and improved every year to be the from our Crew Accessories range: foulards, ties, epaulets, best and most practical uniforms they can have. belts, caps and shoes. Our true versatility can also be seen in our evening range and its unique customer designs, suitable for themed and high glamour events. -

Men's Clothing Title Style Guide

Men’s Clothing Title Style Guide 1. Casual Wear a. Jeans b. Chinos/Casual pants c. T- Shirts d. Polos e. Casual Shirts f. Short 2. Formal Wear a. Suits, Blazers, Formal Jacket, Tuxedos, Suit Jacket, Tuxedo Jacket b. Safari Suit c. Formal Shirt d. Formal Trouser e. Waist coat 3. Outer wear & Sweater a. Jackets/ Track Jacket b. Sweatshirts/ Sweaters/ Hoodie c. Cardigan d. Trench Coats/ Coat e. Gilets 4. Ethnic Wear a. Kurta Pyjamas/ Kurtas b. Bottoms c. Dhotis, Mundus, Lungi d. Jacket & Gilets e. Stoles f. Head gear (Turbans & Safas) g. Cummerbund 5. Active Wear a. Tracksuit/ Base Layers b. Tights & Leggings c. Track pants / shorts 6. Swimwear 7. Men’s Innerwear a. Vest b. Underwear (Briefs, Boxers, Trunks) 8. Sleep & Lounge a. Lounge Bottoms (Lounge Pants, Track Pants, Shorts) b. T-shirts c. Polo 9. Socks & Hoisery 10. Fabrics 1. Casual Wear a. Jeans Parent ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [MODEL NAME] + [FIT NAME] + [“JEANS”] Example - Wrangler Men’s Skanders Slim Fit Jeans - Levis Men’s 501 Skinny Fit Jeans Child ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [MODEL NAME] + [FIT NAME] + [“JEANS”]+ [EAN_MODEL No._COLOR_SIZE] - Wrangler Men’s Skanders Slim Fit Jeans 8902733295314_Blue_34 - Levis Men’s 501 Skinny Fit Jeans 8902733295291_Black_32 b. Chinos/ Casual Pants Parent ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [OCCASSION] + [SUB_CAT] Example - Wrangler Men’s Formal Trouser - Levis Men’s Casual Trouser Child ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [OCCASSION] + [SUB_CAT]+ [COLOR}+ [EAN_MODEL No._COLOR_SIZE] - Wrangler Men’s Formal Jeans 8902733295314_Green_30 - Levis Men’s casual Jeans 8902733295291_Beige_32 c. T-shirts Parent ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [MATERIAL] + [SUB CAT] Example - Lee Men’s Cotton T-shirt Child ASIN [BRAND] + [GENDER] + [MATERIAL] + [SUB CAT] +[COLOR}+ [EAN_MODEL No._COLOR_SIZE] - Levis Men’s Cotton T-shirt 8907036833560_Red_S d.