19-28. Profess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Optometry Cases in “Mayberry”

9/7/2020 Disclosures: Common Optometry CooperVision Cases in “Mayberry” Maculogix IntegraSciences Lessons I Learned From These Cases Frances Bynum, OD COPE 65581-GO 1 2 Case 1: Opie Taylor Case 1: Opie Taylor Hit in the eye with air soft gun Hit in the eye with air soft gun VA: OD: 20/20 SLE: subconjunctival heme in the temporal corner Cornea: clear A/C: clear, no cells Posterior Pole: clear MHx: unremarkable Would you dilate this patient? (Grandmother brought child in) 3 4 Case 1: Opie Taylor Case 1: Opie Taylor Hit in the eye with air soft gun Hit in the eye with air soft gun Commotio retinae Commotio retinae (caused by blunt trauma to the eye) (caused by blunt trauma to the eye) Treatment: Treatment: usually none Prognosis: Prognosis: good, but look for choroidal rupture or RPE break Might use OCT to look for small break 5 6 1 9/7/2020 Case 1: Opie Taylor Case 1: Opie Taylor Hit in the eye with air soft gun Hit in the eye with air soft gun 7 8 Case 2: Barney Fife Case 2: Barney Fife Sudden spot in vision Sudden spot in vision CC: Sudden Spot in his vision this morning VA: OD: 20/20 OS: 20/20 IOP: 12/12 icare @ 8:12am MHx: HTN (uncontrolled at times) Meds: HTN OHx: Toric MF contacts, mild crossing changes consistent with HTN history DFE: heme @ disc 9 10 Case 2: Barney Fife Case 2: Barney Fife Sudden spot in vision Sudden spot in vision BP: 135/85 LA seated @ 8:15am BP: 135/85 LA seated @ 8:15am Management: ??? Management: ??? Upon further questioning……. -

Chapter 1: Attachments

Chapter 1: Attachments ATTACHMENT 1-A: SOLID WASTE AUTHORITY TERM CHARTS 1A-1 APPOINTING AGENCY CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Environmental Protection Austin Caperton, Cabinet Secretary 601 57th St. SE Charleston, WV 25304 Phone: 304-926-0440 Website: www.dep.wv.gov Public Service Commission Michael Albert, Chairman For questions regarding appointments, contact: 201 Brooks Street Jerry Bird, Director of Government Relations Charleston, WV 25301 Phone: 304-340-0843 Website: www.psc.state.wv.us Laura Sweeney, Secretary Phone: 304-340-0306 Phone: 304-340-0301 Toll Free: 800-344-5113 Fax: 304-340-3758 WV Conservation Districts Website: www.wvca.us 1A-2 CONSERVATION DISTRICT CONTACT INFORMATION CAPITOL (CCD) NORTHERN PANDANDLE (NPCD) Kanawha Brooke, Hancock, Marshall, Ohio 418 Goff Mountain Rd. Suite 102 1 Ballpark Drive Cross Lanes, WV 25313 McMechen, WV 26040 Phone: 304-759-0736 Fax: 304-776-5326 Phone: 304-238-1231 Fax: 304-242-7039 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] EASTERN PANHANDLE (EPCD) POTOMAC VALLEY (PVCD) Berkeley, Jefferson, Morgan Grant, Hampshire, Hardy, Mineral, Pendleton 151 Aikens Center, Suite 2 500 East Main Street Martinsburg, WV 25404 Romney, WV 26757 Phone: 304-263-4376 Fax: 304-263-4986 Phone: 304-822-5174 Fax: 304-822-3728 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ELK (ECD) SOUTHERN (SCD) Braxton, Clay, Nicholas, Webster Fayette, McDowell, Mercer, Raleigh, Summers, Wyoming 740 Airport Road 463 Ragland Road Sutton, WV 26601 Beckley, WV 25801 Phone: 304-765-2535 Fax: 304-765-9635 Phone: 304-253-0261 Fax: 304-253-0238 -

Some Help with Home School - Watch Classic Television

Some Help with Home School - Watch Classic Television Disclaimer: I am a former k-12 teacher. I have never been involved in the homeschool movement which some people choose in place of sending their children to traditional schools. The term “Home School” as used here refers to the work that you will do with your children over the next few weeks during the quarantine. Again, these ideas are not vetted by the homeschool movement. However, I was a public school th th teacher for 13 years, teaching 7 and 11 grades. I am National Board-certified in English/Language Arts for Adolescents and Young Adults. I hold an earned Ph.D. in Education. The following advice is offered in a spirit of collaboration with directions from your children’s teachers. -Jeanine A. Irons, Ph.D. Guiding Thought: Use one resource in multiple ways to facilitate learning. It is possible to use relatively ordinary experiences to supplement your children’s education in multiple ways. Classic television shows can lead to rich learning experiences. “The Andy Griffith Show” is one example. This particular show can be viewed on cable tv, Tubi, Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, fuboTV, and Philo. The following information gives some ideas on how to use “The Andy Griffith Show” to facilitate geography, character analysis, handwriting, and/or diversity learning experiences for children of various ages. You can view multiple episodes, in any order*, and use different ideas each time. You can pick and choose from the ideas provided and/or use your own ideas, based on factors you deem significant, such as your children’s ages. -

Take Me Back to Mayberry

TAKE ME BACK TO MAYBERRY Lesson Topic: Fear “High Noon in Mayberry” Date: __________________________ Episode #80 – January 21, 1963 CAST: In Order Of Appearance ANDY TAYLOR Sheriff, Mayberry County BARNEY FIFE Deputy Sheriff, Mayberry County BILLY RAY BELFAST Letter Carrier OTIS CAMPBELL Town Drunk GOMER PYLE Service Station Attendant BEE TAYLOR Andy Taylor’s Aunt OPIE TAYLOR Andy Taylor’s Son LUKE COMSTOCK Ex-Convict Arrested By Andy Taylor Are you scared of the trouble that’s coming? TODAY’S SCRIPTURE: For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love and of a sound mind. II Timothy 1:7 (NKJV) For God did not give us a spirit of timidity – of cowardice, of craven and cringing and fawning fear – but [He has given us a spirit] of power and of love and of calm and well-balanced mind and discipline and self-control. II Timothy 1:7 (Amplified) CLASS ACTIVITY: Divide class into groups of 6-8 members. Give each group the “rating fears” worksheet, and ask them to complete the worksheet. Allow 10-15 minutes for small group discussion. Wrap up the small group session with a brief class discussion. TYPES OF FEAR: Worry harassing trouble; perplexity Anxiety condition of mental uneasiness arising from apprehensive concern Panic a sudden groundless fright Phobia extreme and irrational dislike, aversion, dread, or hatred Take Me Back to Mayberry Fear/Page 2 INTRODUCTION: Fear came into the world with the sin of Adam and Eve (Genesis 3:8-10), and mankind has been dealing with fear since then. -

Armartine Cain

BLOUNTSTOWN HEALTH A ND REHAB CENTER 850-674-4311 AUG 2019 The BHRC Times Blountstown Health and Rehab Center 16690 S.W. Chipola Rd, Blountstown, Fl. 850-674-4311 Jennifer Reyes, Administrator ext. 122 Yadira (Jay) Prowant, Director of Nursing ext. 102 “Our BHRC resident spOtlight” Arma rtine Cain Resident of the Month Armartine has lived most of her life here in Calhoun County. She married James (Joe) Cain who was a pastor. She was always very involved in Church groups & activities. They opened a meat business, made sausage & had a route selling all around the area. Her & her Mother liked to sew & she spent a lot of time helping to raise relatives’ children. Armar tine has always loved children, listening to gospel music & preachers preaching. “Congratulations” Please Lindsey Welcome Laramore LPN BHRC’s Newest Employees AUDREY WARD Recently passed her Florida Mr. Burrell Sumner has been honored with FRENSHELA Nursing State Boards! an Official Proclamation as an “Ambassador Lindsey began working at BHRC as a HOLMES For Peace”. He also received an Certified Nurse’s Assistant in 2016 & “Ambassador For Peace” Medal”. Both of is a vital asset. these are from The Minister Patriots of TATE She went to Tom P. Haney Technical Veterans Affairs, Republic of Korea, for his Center for Nursing. service performed in restoring & preserving BENNETT We are proud to have her on our freedom, democracy and helping reestablish Nursing Team!!! their Free Nation. BLOUNTSTOWN HEALTH A ND REHAB CENTER Social Services, Admission & Marketing Tammy Godwin ext. 103 Resident Choice Meal of the Month Asst, D.O.N. -

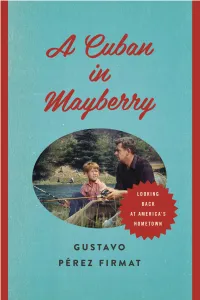

A Cuban in Mayberry THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK a Cuban in Mayberry Looking Back at America’S Hometown

A Cuban in Mayberry THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK A Cuban in Mayberry Looking Back at america’s Hometown Gustavo Pérez Firmat University of Texas Press Austin Copyright © 2014 by Gustavo Pérez Firmat All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2014 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713- 7819 http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp- form ♾ The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/niso Z39.48- 1992 (r1997) (Permanence of Paper). LiBrary of congress cataLoging- in- Publication Data Pérez Firmat, Gustavo, 1949– A Cuban in Mayberry : looking back at America's hometown / Gustavo Pérez Firmat. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isBn 978-0-292-73905-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Andy Griffith show (Television program) 2. City and town life on television. I. Title. Pn1992.77.a573P39 2014 791.45′72—dc23 2014007098 doi:10.7560/759251 For Jen and Chris Holloway Tell me a story of deep delight. roBert Penn warren Contents Acknowledgments ix introDuction. To the Fishing Hole 1 Part One: tHe PLace cHaPter one. A World unto Itself 21 cHaPter two. Against Change 35 cHaPter tHree. Stopping the Story 47 cHaPter four. Great Pages in History 56 cHaPter five. From R.F.D. to R.I.P. 67 interLuDe: The Road to Mayberry 79 Part Two: tHe People cHaPter one. Sheriff without a Gun (Andy) 89 cHaPter two. Imagination (Mr. McBeevee) 97 cHaPter tHree. -

Saint Elizabeth's Church

Saint Elizabeth’s Church []]--"20##2 0'12-*Q&-"#1*,"VX^V_ 11!&#"3*# #!2-07SZVWX[YV^Y\\#6SZVWX[YV]\_[ XrrxrqHhr) 555T1',2#*'8 #2&!&30!&T,#2 #V+'*S-$$'!#1',2#*'8 #2&!&30!&T,#2 #4T#,07T',,-Q0TQ"+','1202-0 #4T-1M"T-!&Q12-0*11-!'2# !" $ 0'1&2$$ XrrxqhHhh&)"hivyvthy) IHhUu qh 0T0#,#1!- 0Q12-0*11'12,2 Cy9hsPiyvthvhqCyvqh) 1T&0*#,#,"0"#Q--))##.#0 #!0#207 0T-<-#"#'0-1Q--0"',2-0-$ !'*'2'#10-3,"1%+2T #.2'1+ '2&-0+2'-,Q+'*72#!'1-32&','1207 VRSTWUVUWRS-0!!"-$$'!#12#*'8 #2&0'T!-+ -V'0#!2-001T0#,-12 %.-,1-0'$'!2#1 -V'0#!2-001T0'-,,'#02',1 31'!','1207 '00'%# 0T-&,04#01Q!0%,'12 0T-1#.&##$#+-1Q!0%,'12 '11&'!-*#-31Q!0%,'12 M 0312##13"'2-01 #!-,!'*'2'-, 0T7+-,"-0"#'0-0T,3#*-1 !"#$M!"%$ 0T-1#.&'40T4'"!*'4#'0 0'1&0%,'82'-,1 ,-',2',%-$2&#%'!) TW$##)*3 01T!07,,('+Q--0"',2-0 & ',,!#-3,!'*0T-&,#%-Q&'0+, 0'#,"1-$*2T+*'8 #2&01T--+'0.#,2#0Q0#1'"#,2 '2#-$&&0'12',*,'2'2'-,-$"3*21 .,'2#"/0-2�&--"-$2�-*7*.'0'2,"2�-*710','27V 0T #0,,"-/03+Q0#1'"#,2 ' 03.-"#!0I<-V#4'"--4\031,<-&:0#3,'#1T 0-*7-107*-"*'2701T0'#-220#**Q0#1'"#,2 -*70"#01 -!2'-,12-2�'#12&--" *,2-0'12-0T-<-#"#'0-1Q0#1'"#,2 ( ) * + ,- 0'#,"1-$ 2T*'8 #2&V0'1&320#!&,"11'12,!# ( . /!$0122030204 M !"#$ R Nip It! Nip It in the Bud! ~ Posted Thursday, June 3, 2021 RI Catholic Fans of the venerable TV program, the “Andy Griffith Show” will immediately recognize the names of the principal players: Sheriff Andy Taylor, Deputy Barney Fife, Opie Taylor, and Aunt Bee. -

January 2020 Issue 1 Page 1

January 2020 Issue 1 Page 1 TIM TALK “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Mayberry” In his book, All I Really Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, Robert Fulghum tells of the life lessons he learned. Even though the stories in his book span an entire lifetime; the basics of those lessons learned, he was taught, as he says: “in the sandpile at Sunday School.” From sharing everything and playing fair to eating warm cookies with cold milk and flushing Fulghum says “everything you need to know is in there somewhere. The Golden Rule and love and basic sanitation… …Think what a better world it would be if we all ─ the whole world ─ had cookies and milk about three o’clock every afternoon and then lay down with our blankies for a nap.” After almost nine years of watching episodes of the Andy Griffith Show every Sunday night for church I, like Fulghum, have learned many life lessons; not from kindergarten, but from characters like Barney Fife, Opie Taylor, Helen Crump, Gomer Pyle, Floyd Lawson, Aunt Bee, Otis Campbell and Andy Taylor. Some of those lessons learned come from the zaniest of mishaps in Mayberry, like the time Ernest T. Bass threw rocks through the windows of the court house, instead of hauling him off to jail, Andy instead invested himself into transforming Ernest into a well-mannered and respected citizen (it worked for a little bit, if I recall correctly). Or how about the time Opie became so critical of his Aunt Bee’s fishing abilities that Andy took it upon himself to teach his son to see the good in everyone. -

January 2016

January 2016 Richmond Senior Center News 1168 Main Street (Second Floor) Wyoming, RI 02898 E-mail: [email protected] Mailing address: Richmond Senior Center c/o Richmond Town Hall 5 Richmond Townhouse Road, Wyoming, RI 02898 Telephone—401-491-9404 Center Hours—Staffed Daily From the Chairman—Dennis McGinity M-F 8:30 am to Noon Note: The Center follows the Chariho School District for inclement Weather closings. Senior Center Committee Members Dennis McGinity—Chairman Tom Dufficy—Vice Chairman & Secretary Richard Millar—Financial Liaison What a great year 2015 has been. I want to thank all Jackie Lombardo—Bingo Chair Dottie Barber—Activities Chair members for your support. Thank to our volunteers Pasquale DeBernardo who make the Center run so well. Your commitment Newsletter Editor—Dennis McGinity is outstanding. Our members are the best. A special Thank you to Joe Reddish for his help with the Christ- Next monthly members meeting mas Party. I’m looking forward to 2016 so until then. Will be held at 11 AM on January 14, 2016 Have a Happy and Healthy New Year... Come and get involved The visiting nurse is here on the Third Thursday of each month at 9:30 AM Please let the Senior Center office know of any changes to your address, phone number or email address. We want to keep all records up to date. Keeping you informed is important to us. New Members—Welcome Jean Norton—Phoebe Smith Dennis Desjardin Janice Sevigny & Marie Hargreaves Mark the Date New Arts & Crafts Program Starting Friday Jan 8, 2016 At 10:30 am Mystery Lunch -

Prisoner of Love Free

FREE PRISONER OF LOVE PDF Jean Genet,Ahdaf Soueif,Barbara Bray | 430 pages | 31 Jan 2003 | The New York Review of Books, Inc | 9781590170281 | English | New York, United States Prisoner of Love (Video ) - IMDb Title: Prisoner of Love Video Flint, an escaped convict takes refuge in a country house owned by Sonia, a woman who is thinking of Prisoner of Love the property to a developer named Len Burns, who plans of building a prison. Cash Prisoner of Love, porn's prolific but untalented screenwriter, sabotages this little movie that dares the viewer to stick with his dumb story. Intentionally silly dialog is part of his usual mockery of porn having a story line, insulting the viewer. Set-up has Tom Byron as stock villain, callous real estate developer out to buy land to build an annex to an overcrowded prison Prisoner of Love miles away. Danielle Rogers stars as the housekeeper for the estate on that land, owned by a mysterious Mr. Blacksworth, who is much talked about but never shows up in the movie. He steals Tom's clothes and poses as Blacksworth, who is supposed to be visiting the property. Director Scotty Fox intercuts two sex scenes at this point in the farcical narrative: cook Rayne humping long-haired groundskeeper Buster Cheri in the kitchen, while Alicyn Sterling immediately services Spears Prisoner of Love a Prisoner of Love shed. This is Alicyn before her famous boob job, quite Prisoner of Love with natural small breasts and immensely puffy nipples. Continuity is thrown to the winds, as all four actresses in the cast suddenly "put on a show" for the fake visiting Blacksworth, a lesbian foursome outside on that blanket.