ACTION SPORTS in TRANSITION: OPTIMIZING PERFORMANCE By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Grand Prix Olympic Selection Rankings - Google Docs

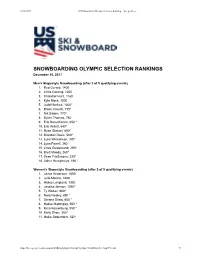

12/10/2017 2018 Grand Prix Olympic Selection Rankings - Google Docs SNOWBOARDING OLYMPIC SELECTION RANKINGS December 10, 2017 Men's Slopestyle Snowboarding (after 2 of 5 qualifying events) 1. Red Gerard, 1400 2. Chris Corning, 1200 3. Chandler Hunt, 1160 4. Kyle Mack, 1000 5. Judd Henkes, 1000* 6. Brock Crouch, 770* 7. Nik Baden, 770* 8. Dylan Thomas, 760 9. Eric Beauchemin, 650 * 10. Eric Willett, 640* 11. Ryan Stassel, 600* 12. Brandon Davis, 500* 13. Luke Winkelman, 370* 14. Lyon Farrell, 360 * 15. Chas Guldemond, 290* 16. Brett Moody, 260* 17. Sean FitzSimons, 220* 18. Asher Humphreys, 160 * Women's Slopestyle Snowboarding (after 2 of 5 qualifying events) 1. Jamie Anderson, 1800 2. Julia Marino, 1600 3. Hailey Langland, 1300 4. Jessika Jenson, 1050* 5. Ty Walker, 900* 6. Nora Healey, 850 * 7. Serena Shaw, 680 * 8. Hailee Mattingley, 550 * 9. Kirra Kotsenburg, 550 * 10. Karly Shorr, 360* 11. Haille Soderholm, 320* https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BDigbyEqAobXdxlqYGy0QkreYmIZSDjbiXx67fyq3CU/edit 3/4 12/10/2017 2018 Grand Prix Olympic Selection Rankings - Google Docs Men's Halfpipe Snowboarding (after 1 of 4 qualifying events) 1. Ben Ferguson, 1000 2. Shaun White, 800 3. Danny Davis, 600* 4. Gabe Ferguson, 500* 5. Chase Josey, 450* 6. Greg Bretz, 400* 7. Louie Vito, 360* 8. Jake Pates, 320* 9. Ryan Wachendorfer, 290* 10. Chase Blackwell, 260* 11. Toby Miller, 240* 12. Matt Ladley, 220* 13. Josh Bowman, 200* 14. Brett Esser, 180* Women's Halfpipe Snowboarding (after 1 of 4 qualifying events) 1. Chloe Kim, 1000 2. Maddie Mastro, 800 3. -

1 SNOWBOARDING SPORT COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES U.S. Ski & Snowboard Congress 2018 Center of Excellence, 1 Victory Lane, Park

SNOWBOARDING SPORT COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES U.S. Ski & Snowboard Congress 2018 Center of Excellence, 1 Victory Lane, Park City, UT May 3,2018 COMMITTEE MEMBERS Mike Mallon – USASA Rep - present Alex Deibold – Athlete Rep - present Tricia Byrnes – Athlete Rep - present Ross Powers– Eastern Rep – present Coggin Hill – PNSA Rep – phone Paul Krahulec – Rocky Rep – excused Andy Gilbert – Intermountain Rep - phone Jessica Zalusky – Central Rep - phone Jeremy Lepore – IJC Rep - phone Peter Foley – Coaches Rep - present Ben Wisner – Far West Rep – present Mike Mallon – USASA Rep - present OTHERS IN ATTENDANCE Jeremy Forster – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Jeff Juneau – Killington Mtn School Dave Reynolds – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Tori Koski – SSWSC Nick Poplawski– Park City Ski & Snowboard Ben Wisner – Mammoth Mike Ramirez - U.S. Ski & Snowboard Lane Clegg – Team Utah Nichole Mason – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Rob LaPier – Jackson Hole via phone Mike Jankowski – U.S. Ski & Snwoboard Jeff Archibald – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Lisa Kosglow – U.S. Ski & Snowboard BOD Kim Raymer – USASA BOD Lane Clegg – Team Utah Rick Shimpeno – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Cath Jett – CJ Timing Kelsey Sloan – U.S. Ski & Snowboard CB Betchel – Crested Butte Jake Levine – Team Utah Matt Vogel – Team Summit Gregg Janecky – Northstar / HCSC Sarah Welliver – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Aaron Atkins – Eric Webster – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Jason Cook – AVSC Ross Hindman – ISTC Jeff Juneau – KMS Nick Alexakos – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Jeff Archibald – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Michael Bell – Park City Ski & Snwoboard Tom Webb – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Sheryl Barnes – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Tom Kelly – U.S. Ski & Snowboard Ritchie Date – U.S. -

Shaun White Has Been Flying Higher Than Anyone Since He Was Seven Years Old

Shaun White has been flying higher than anyone since he was seven years old. But at 23, the world’s greatest snowboarder has no idea where he’s going to land next By Vanessa GriGoriadis photoGraphs By terry richardson 40 • Rolling Stone, March 18, 2010 SHAUN WHITE the presence of rock heroes, I decided that up there spinning, like, ‘Where am I?’ and under the mentorship of Tony Hawk, who I had to get the pants to match.” your life depends on finding the blue line considered him the most promising young So here he is, our leather-ensembled marking the pipe. It’s kind of like tennis: skater he had ever seen. “Shaun’s confi- two-time gold medalist über rock fan, You have to be quick and react quick.” dence is a family thing,” says his brother, 23, holding court with his team manager, On TV, White may play the eternal rad- Jesse. “Our mom moved to Hawaii on her bodyguard and two PR reps at a table in an ical little dude – a goofy guy whose radi- own when she was 18, and my dad marches upscale bistro in downtown Manhattan a calism is sweetly unthreatening – but in to the same drummer. He just has it on day after leaving Vancouver, with only a person, he’s not only intelligent and so- the inside.” brief stop in Chicago to school Oprah in phisticated but a stone-cold killer. Like White’s mom, a waitress, and father, a the rigors of the double McTwist 1260: his Tiger Woods, whom White has called a city employee, brought him up with a pro- showstopping trick, made up of two flips “great guy deep down who just made some gressive attitude in Del Mar, a beachfront and three and a half spins, that he stuck bad calls,” he’s as competitive about busi- town near San Diego – he was named after at the Olympics after he won the gold – a ness as he is about sports: Between his own a professional surfer, Shaun Tomson, and “righteous victory lap,” as he put it. -

Snowboarders Beef up Beijing Preparations

20 | Monday, August 30, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY SPORTS WINTER OLYMPICS By SUN XIAOCHEN [email protected] ar from the slopes, China’s I’ve gained more top snowboarders are tak- Snowboarders beef up muscle obviously on ing cues from inside the Octagon as they shape up my body and Fand toughen up for next year’s Bei- improved my core jing Winter Olympics. As part of an agreement between strength to potentially Ultimate Fighting Championship hang in the air longer, and the Chinese Olympic Commit- Beijing preparations tee, the Las Vegas-based mixed mar- which makes it tial arts organization opened its possible for me to do Performance Institute in Shanghai to Liu Jiayu and Cai Xuetong last UFC lends a hand with tailor-made training for Winter Olympians more difficult tricks.” month, with the two riders undergo- Liu Jiayu, ing tailor-made strength and condi- on her training at the UFC Per- tioning programs. formance Institute in Shanghai Already, the pair are encouraged by the results as they smash through their physical limits ahead of the all- little advantage she can find as she important Olympic season. prepares to battle it out with defend- “The training here is customized, ing Olympic champion Chloe Kim of data-driven and guided one-on-one. the United States. Everything is measurable here. It’s “To be competitive at the Olym- really about yourself and targets pics, you definitely need break- where you need to improve urgent- throughs each and every time,” said ly,” Liu, a halfpipe silver medalist at Liu, who was beaten to silver by Kim the 2018 Winter Olympics in South by an 8.5-point margin in the final at Korea, said in an online interview the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang. -

PIM 2C - Section 1: Precision Accuracy 2 Canadian Sport Parachuting Association

PARACHUTIST INFORMATION MANUAL Part Two C Advanced © Canadian Sport Skydiving Skills Parachuting Association 300 Forced Road May 2004 Russell, Ontario K4R 1A1 Draft PIM 2 C ADVANCED SKYDIVING SKILLS TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: PRECISION ACCURACY ……………………………… 1 SECTION 2: SPEED STYLE …………………………………………. 13 SECTION 3: INTRODUCTION TO SKYSURFING ……………… 25 SECTION 4: CAMERA FLYING …………………………………….. 34 SECTION 5: INTRODUCTION TO FREE FLYING SIT FLYING .. 42 SECTION 6: CANOPY REALITIVE WORK ………………………... 55 SECTION 7: DEMOSTRATION JUMPS AND THE EXHIBITION JUMP RATING …………………………………………. 73 SECTION 8: INTRODUCTION TO FREE FLYING HEAD DOWN ……………………………………………. 83 Canadian Sport Parachuting Association 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: PRECISION ACCURACY The Starting Point ………………………………………………………….. 2 Preparation …………………………………………………………………. 2 In-flight …………………………………………………………………….. 2 Canopy Control ……………………………………………………………. 3 a) The Set-Up Point …………………………………………………... 3 Set-up Point Selection…………………………………………… 3 Crosswind ………………………………………………………. 3 Into the Wind……………………………………………………. 4 Flying to the set-up Point ………………………………………. 5 b) Angle Control on the Glide Slope ………………………………. … 5 Adjustments to the Glide Slope ……………………………… 5 Advanced Techniques ……………………………………………………... 6 a) Rolling On ………………………………………………………….. 6 b) Foot Placement Techniques ……………………………………….. 7 Unusual Situations ………………………………………………………… 8 a) Thermals …………………………………………………………… 8 b) Cutaways …………………………………………………………… 8 Equipment …………………………………………………………………. 8 a) Harness and Containers ………………………………………… . -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background At the present time, extreme games are becoming popular around the world which most of the sports were invented in the US. The most practical and flexible is skateboarding. Skateboarding at first was invented by the surfers who wanted to surf without the needs of waiting for the waves at the beaches. Therefore they made ramps as a replication of an undergoing wave portraying as skaters do the drop in from up of the ramp. That kind of things are still available nowadays, but the most practical things that everyone can actually do in many places is the street skateboarding. It is also a way of life where the skaters go find some spots with a good environment such as smooth roads, stairs, rails, empty swimming pools, etc to skate in. There are many things that skaters can do in street skateboarding because basically street skating has no rules and regulation unlike basketball or soccer. Also it is easy to skate in many good places as long as the environment supports the needs of the skater’s skateboarding capability which that means skills in mastering skateboarding techniques are really matters in finding the spots that matches personal ability, strength and guts. At first many people would think that skateboarding is an easy sport activity because they can witness from TV or videos how easy the skaters do their tricks and 1 2 somehow the tricks tend to be the same thing over and over where in reality it doesn’t. Most of the tricks in skateboarding are very hard to learn and it really depends on the skaters themselves. -

WOMEN in the 2018 OLYMPIC and PARALYMPIC WINTER GAMES: an Analysis of Participation, Leadership, and Media Coverage

WOMEN IN THE 2018 OLYMPIC AND PARALYMPIC WINTER GAMES: An Analysis of Participation, Leadership, and Media Coverage November 2018 A Women’s Sports Foundation Report www.WomensSportsFoundation.org • 800.227.3988 Foreword and Acknowledgments This report is the sixth in the series that follows the progress of women in the Olympic and Paralympic movement. The first three reports were published by the Women’s Sports Foundation. The fourth report was published by SHARP, the Sport, Health and Activity Research and Policy Center for Women and Girls. SHARP is a research center at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Research on Women and Gender, co-founded by the Women’s Sports Foundation. The fifth report, published in 2017 by the Women’s Sports Foundation, provided the most accurate, comprehensive, and up-to-date examination of the participation trends among female Olympic and Paralympic athletes and the hiring trends of Olympic and Paralympic governing bodies with respect to the number of women who hold leadership positions in these organizations. The sixth report examines the same issues for the 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. It is intended to provide governing bodies, athletes, and policymakers at the national and international level with new and accurate information with an eye toward making the Olympic and Paralympic movement equitable for all. These reports can be found at: https://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/research/articles-and-reports/all/ The Women’s Sports Foundation is indebted to the study authors, Emily Houghton, Ph.D., Lindsay Pieper, Ph.D., and Maureen Smith, Ph.D., whose research excellence brought this project to fruition. -

LAAX OPEN 2019 Offers Freestyle at Its Finest: Olympic Champions Such As Anna Gasser, Sebastien Toutant and Iouri Podladtchikov Confirm Their Entry

Press Release LAAX OPEN 2019 offers freestyle at its finest: Olympic champions such as Anna Gasser, Sebastien Toutant and Iouri Podladtchikov confirm their entry (LAAX, Switzerland – 18 December 2018) – Winter season is under way: in the leading freestyle resort of LAAX and on the international snowboarding circuit. The LAAX OPEN will take place next month, from 14 to 19 January 2019. The FIS Snowboard World Cup and elite World Snowboarding event, featuring prize money of CHF 200,000, attracts professional snowboarders from all over the world to LAAX, in the canton of Graubünden (Grison). 2018 Olympic champions Anna Gasser (AUT) and Sebastien Toutant (CAN) have confirmed their participation, along with OPEN event champions Christy Prior (NZL) and Iouri Podladtchikov (SUI). Entries for the Slopestyle and Halfpipe competitions have been received from 19 different countries spanning five continents. Preparations are now in full swing with the organiser for an action- packed LAAX OPEN. The OPEN in LAAX has always been an absolute must for competitive snowboarders. They love the perfectly groomed freestyle facilities, the powder day, music, entertainment and spectators. LAAX is many people’s favourite resort, and riders from all over the world feel right at home here. Such as Seb Toutant, junior champion in the Burton European Open in LAAX in 2008, third place in the Slopestyle event at the LAAX OPEN 2016 and Olympic champion in 2018. “Why I like LAAX so much is cause of the mountain, there is like powder everywhere, there is like really good park, and probably this mountain has the most beautiful view in the background. -

March 2019 1 the Bulletin RUAPEHU SKI CLUB CONTENTS Volume 84, No

The Bulletin, March 2019 1 The Bulletin RUAPEHU SKI CLUB CONTENTS Volume 84, No. 1 March 2019 2 President’s column 3 Ruapehu news 5 Ski season bookings 6 House committee 7 Snow squads/Academy 8 Amazing ski run 8 New members 8 RSC obituaries 9 Dunny trouble 11 Julien Temm 14 Zoi wins world title 15 Zoi wins X Games 16 World ski champs 17 RSC calendar 19 Record numbers 19 Home made lava 21 Piera wins points 25 Adriaansen travels 28 Tussock traverse 30 World snow news Jennifer and EJ Moffat outside the RSC Lodge. 32 RSC info page Moffat photo. 2 The Bulletin, March 2019 PRESIDENT’S COLUMN will be consumed by maintenance, instead of the improvements we all seek. Welcome back from the holidays. Work parties also provide a vital role in Hoping everyone had a joyous festive on-boarding new members into mountain season and an enjoyable break. and Club life. At the same time, they give While we have been savouring the the rest of us an opportunity to meet other fabulous stretch of fine weather and members and socialise with them. the beach, RAL have been toiling away Your Committee deserves mention, as with the construction of the Whakapapa we move forward into a new year. Their Gondola. I’m sure we are all wish RAL dedication and efforts benefit all club best of luck for a pre-season completion. members, both present and future. Now that holiday times are over and the We have a relatively large Committee, kids are back at school we can think about with 21 members in all. -

Arena Skatepark Dan Musik Indie

1 ARENA SKATEPARK DI YCGYAKARTA BAB2 Arena skatepark dan Musik Indie Skat.park dan pembahasannya 1. Skateboard dan pennainannya Skateboard adalah sualu permainan, yang dapat membcrikan suasana yang senang bagi pelakunya. Terlebih jika tempat kita bermain adalah tempat yang selafu memberikan nuansa baru; dalam hal ini adalah tempat yang dirasakan dapot memberikan variasi-variasi baru dalam bermain, dengan alat alat yang cenderung baru pula. Yang terjadi di luar negri (kasus di Amerika Serikat dan negara-negara Eropa), banyak tempat-tempat pUblik/area-area properti orang, yang sudah tertata secara arsitektural dengan baik; cenderung menjadi sasaran para pemain skateboard untuk dijadikan spot bermain skateboard. Dengan kecenderunyan bermain dijalanan, tentunya juga bakalan mengganggu keberadaan aktivitas yang lainnya. Tempat-tempat yang dibagian HAD' PURo..ICNC 9B 512 1 B6/ TUBAS AKHIR 16 I_~ ARENA SKATEPARK 01 YCGYAKARTA gedungnya terdapat ledge, handrail, tangga, dan obstacle-obstacle adalah sasoran yang selalu dijadikan tempat untuk bermain. Baik untuk dilompatL meluncur, ataupun untuk membenturkannya. Dengan demiklan kegiatan kegiotan ini sering dianggap illegal dan melawan hukum, korena merugikan dan cenderung merusak properti publik. Namun keberagaman spot di jalanan, terus dan terus mendorong para pemain skateboard untuk bertahan dan mencari spot-spot baru untuk dimainkan, dengan tetap beresiko ditangkap aparat keamanan. Kecenderungan gaya permainan street skateboarding inilah yang sekarang sedang menjadi trend di dunia skateboarding. Bermain di tempat yang selalu memberikan varias; komposisi obstacle yang selalu baru dan nuansa suasana baru, cenderung membuat pola permainan yang mengalir dan tidak membosankan. Kemenerusan trik yang dimainkan secara berurutan, dengan pola permainan yang mengalir dan didukung oleh komposisi alat yang tepat. Skatepark yang ada selama inL cenderung secara peruangan memberikan batasan antara ruang indoor dan outdoor. -

19-23 January 2021 FIS Snowboard World Cup in Slopestyle and Halfpipe Confirmed

Press release LAAX, Switzerland, 2 October 2020 LAAX announces date for LAAX OPEN 2021: 19-23 January 2021 FIS Snowboard World Cup in Slopestyle and Halfpipe confirmed The LAAX OPEN, Europe’s long-standing and number one snowboarding event, is scheduled for 19-23 January 2021. International snowboard pro riders will take part in the Slopestyle and Halfpipe disciplines in the World Cup on Crap Sogn Gion, where they will demonstrate top-class freestyle skills and vie for points, prize money and prestige. This was confirmed this week during the digital FIS conference. The FIS has announced that the 2020/2021 tour will go ahead thanks to a compact concept, with the freestyle World Cup circuit taking place in the form of a safe bubble through close cooperation with the local organizers. The FIS Snowboard World Cup in LAAX takes place as part of the European package at the beginning of the new year. LAAX has been leading the way in freestyle for over three decades and has been voted the ‘World’s Best Freestyle Resort’ by the public and jury four years in a row at the World Ski Awards. The multiple-awarded resort continues to step forward as a freestyle trailblazer even in extraordinary times and is taking every step necessary to ensure a safe winter season and World Cup. During the summer, LAAX confirmed to its association partners that it would make no compromises when it comes to sport and would continue to organise the competitions for women and men in both Slopestyle and Halfpipe. There is a huge undertaking involved in getting everything set up perfectly, but this decision is a commitment for the riders and their sport. -

P17 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22, 2014 SPORTS Sochi still scrambling to sell Olympic tickets LONDON: What if they held an Olympics and popular events being hockey, biathlon, figure skat- before the games. Tickets have been sold on Sochi’s “We experienced demand at expected levels,” nobody came? The situation isn’t that bleak, of ing, freestyle and snowboard,” the organizing com- official website on a first-come, first-served basis. spokesman Michael Kontos said, without giving fig- course, for the Sochi Games. Yet, with less than three mittee said in a statement to the AP. “With 70 per- Box offices are now open in Moscow and Sochi. The ures. Flights to Sochi are expensive, and most inter- weeks to go until the opening ceremony, hundreds cent of tickets already sold and another ticketing cheapest tickets go for 500 rubles ($15), the most national travelers have to go through Moscow, with of thousands of tickets remain unsold, raising the office opening shortly, we are expecting strong last- expensive for 40,000 rubles ($1,200). More than half direct flights to Sochi only available from Germany prospect of empty seats and a lack of atmosphere at minute ticket sales and do not envisage having of all tickets cost less than 5,000 rubles ($150). The and Turkey. Western travelers must navigate the Russia’s first Winter Olympics. empty seats.” Sochi officials have refused to divulge average monthly salary in Russia is 30,000 rubles time-consuming visa process and requirement to There are signs that many foreign fans are staying how many tickets in total were put up for sale, say- ($890).