City Center 55Th Theater (Formerly Mecca Temple)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19Th Annual Valentines Day Winter Ca

W PRESSRELEASES 2/7/69 - 4/8/69 #778 Miss Harlem Beauty Contest Applications Available #779 19th Annual Valentines Day Winter Carnival In Queens (Postponed Until Friday, February 21, 1969) #780 Police Public Stable Complex, 86th St., Transverse, Central Park #781 Monday, March 10th, Opening Date For Sale of Season Golf Lockers and Tennis Permits #782 Parks Cited For Excellence of Design #783 New York City's Trees Badly Damaged During Storm #784 Lifeguard Positions Still Available #785 Favored Knick To Be Picked #786 Heckschers Cutbacks In State Aid to the City #787 Young Chess Players to Compete #788 r Birth of Lion and Lamb #789 Jones Gives Citations at Half Time (Basketball) #790 Nanas dismantled on March 27, 1969 #791 Birth of Aoudad in Central Park Zoo #792 Circus Animals to Stroll in Park #793 Richmond Parkway Statement #794 City Golf Courses, Lawn Bowling and Croquet Cacilities Open #795 Eggs-Egg Rolling - Several Parks #796 Fifth Annual Golden Age Art Exhibition #797 Student Sculpture Exhibit In Central Park #798 Charley the Mule Born March 27 in Central Park Zoo #799 Rain date for Easter Egg Rolling contest April 12, original date above #800 Sculpture - Central Park - April 10 2 TOTAL ESTIMATED ^DHSTRUCTION COST: $5.1 Million DESCRIPTION: Most of the facilities will be underground. Ground-level rooftops will be planted as garden slopes. The stables will be covered by a tree orchard. There will be panes of glass in long shelters above ground so visitors can watch the training and stabling of horses in the underground facilities. Corrals, mounting areas and exercise yards, for both public and private use, will be below grade but roofless and open for public observation. -

Murdoch's Global Plan For

CNYB 05-07-07 A 1 5/4/2007 7:00 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES Portrait of NYC’s boom time Wall Street upstart —Greg David cashes in on boom on the red hot economy in options trading Page 13 PAGE 2 ® New Yorkers are stepping to the beat of Dancing With the Stars VOL. XXIII, NO. 19 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM MAY 7-13, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 3 Times Sq. details its growth, worries Murdoch’s about the future PAGE 3 global plan Under pressure, law firms offer corporate clients for WSJ contingency fees PAGE 9 421-a property tax Times, CNBC and fight heads to others could lose Albany; unpacking out to combined mayor’s 2030 plan Fox, Dow Jones THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 BY MATTHEW FLAMM BUSINESS LIVES last week, Rupert Murdoch, in a ap images familiar role as insurrectionist, up- RUPERT MURDOCH might bring in a JOINING THE PARTY set the already turbulent media compatible editor for The Wall Street Journal. landscape with his $5 billion offer for Dow Jones & Co. But associ- NEIL RUBLER of Vantage Properties ates and observers of the News media platform—including the has acquired several Corp. chairman say that last week planned Fox Business cable chan- thousand affordable was nothing compared with what’s nel—and take market share away housing units in the in store if he acquires the property. from rivals like CNBC, Reuters past 16 months. Campaign staffers They foresee a reinvigorated and the Financial Times. trade normal lives for a Dow Jones brand that will combine Furthermore, The Wall Street with News Corp.’s global assets to Journal would vie with The New chance at the White NEW POWER BROKERS House PAGE 39 create the foremost financial news York Times to shape the national and information provider. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

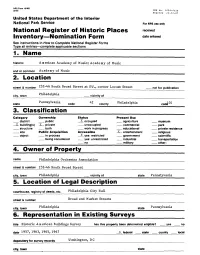

Academy of Music; Academy of Music_____ and Or Common Academy of Music______2

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_________________ 1. Name___________________ historic______American Academy of Music; Academy of Music_____ and or common Academy of Music_______________________ 2. Location_________________ street & number 232-46 South Broad Street at SW., corner Locust Street not for publication Philadelphia city, town vicinity of P ennsylvania 42 county Philadelphia state code CO 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum _ K- building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition, Accessible X entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted __ industrial transportation .... no military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name Philadelphia Orchestra Association street & number 232-46 South Broad Street city, town Philadelphia vicinity of state Pennslyvania 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Philadelphia City Hall street & number Broad and Market Streets city, town Philadelphia state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic American Buildings Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1957, 1963, 1965, 1967 JL federal state county local depository for survey records W ashing ton, D C city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered ^ original site good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Interior Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance This free standing brick Renaissance Revival Style building exhibits a free use of classical forms. -

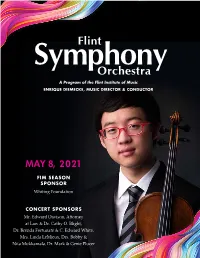

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

Masonic Temple Marks Centennial of Norman Hall Decoration Food \,·Ill Be Scru·D F10m I :00 P.M .To 6:00 P.M

l 100th Birthday! Eastern Pennsylvania JIA Bro. Wesley W. Cheese Masomc Picrnc man (center) of Melita Lodge No. 295, Phila SATURDAY, J l':"E 15, 1991 delphia, on May 16, 1990, his lOOth birthday, with Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom Past Masters Bro. Robert Allentown, Pennsylvania A. Detweiler (left), the 10:00 a.m . to 10:00 p.m. AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL GRAND LODGE OF FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS OF PENNSYLVANIA Senior P.M. of Melita, and Bro. George S. Peck, . \thm~~ion to Dorm•, ,md \\'i ld \\'ater VOLUME XXXVIII MAY 1991 NUMBER2 P.M. (right). Kingdom. im ludmg ,dl 1ide~. pal king a nd :) hours of fO<xl and sod.t: S20.00 ~cnio1 Cititt'Jh "61 \ear~ \atlllg·· .md children 2 \t'ats to 6 n.n~: IR.JO Chilthcn unde1 ~ \l'<ll~: Flee Masonic Temple Marks Centennial of Norman Hall Decoration Food \,·ill be scru·d f10m I :00 p.m .to 6:00 p.m. 1891-1991 . Location: Routt' 22~ ,md :W9. Room lm 1.000. Fil'>t tomt'. fir-,t Jt· ~('ncd. Bro. Wesley W. Cheeseman of Melita for many years. A life member, he Fndmcd i-, m~ <hn k fm Lodge No. 295, Philadelphia, on May 16, regularly makes a cono·ibution to the £01 tit kt·h. :\I.tke <ht •t k p.l\ .thlt· 1990, celebrated his IOOth birthday. Bro. Lodge each December. On his birthday, to: ":\I.t.,oni< Pit nu ... Cheeseman, 79 years a Mason, followed a plaque was presented to him by the in the footsteps of his father, John W. -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

June 2020 No

Grand Lodge Office: 478-742-1475 Please send changes of address to the Grand Secretary MASONIC MESSENGER at 811 Mulberry Street, Macon, GA 31201 Vol. 116 June 2020 No. 1 on your lodge secretary’s monthly report. The editor does NOT keep the list of addresses. Table of Contents Grand Lodge Officers Grand Lodge Notices and Events From the Desk of the Grand Secretary....................................3 Grand Master Johnie M. Garmon (114) Freemasonry Around Georgia.................................................4 Deputy Grand Master Jan M. Giddens (33) Grand York Rite News...........................................................5 Grand Orient of Georgia News..............................................6 Senior Grand Warden Donald C. Combs (46) Articles Junior Grand Warden Michael A. Kessler (216) “History of Dallas Lodge No. 182”......................................7-9 “Operative, Speculative, and Oline”..................................10-11 Grand Treasurer Larry W. Nichols (59) “Crypta Podcast Interview”..............................................12-14 “The 50 Year Mason: A Cut Above”.................................15-17 Grand Secretary Van S. McGee (26, 70) “The Freemasons & the Catholic P...”...............................18-20 “Pakistan’s Freemasons”........................................................21 Review of Georgia Grand Masters and their Tokens.............22 Grand Chaplain James R. Harris (205, 758) “Relevancy to the Community”............................................23 From the Archives “Consolidation (1931)..............................24 -

Edith Cowan College Registered Agents List - January 2019

Edith Cowan College Registered Agents List - January 2019 Agent Name Main Email Phone Address City State/Province Post Code Country Study Care - Tirana [email protected] Abdyl Frasheri Street Tirana 1000 Albania Bridge Blue Pty Ltd - Albania [email protected] 377 45 255 988 K2-No.6 Rruga Naim Frashëri Tiranë 1001 Albania Follow Me 4 English [email protected] 213 554 122 834 Cite 20 Aout 1955, N.59, Oued El Romane El Achour Algiers 16000 Algeria MasterWise Algeria [email protected] 213 021 27 4999 116 Boulevard Des Martyrs el Madania Algiers 16075 Algeria Latino Australia Education - Buenos Aires [email protected] 54 11 4811 8633 Riobamba 972 4-C / Capital Federal Buenos Aires 1618 Argentina CW International Education [email protected] 54 11 4801 0867 J.F. Segui 3967 Piso 6 A (1425) Buenos Aires C1057AAG Argentina Mundo Joven Travel Shop - Buenos Aires [email protected] 54 11 43143000 Marcelo T. de Alvear 818. Ciudad de Buenos Aires. (C1058AAL) Buenos Aires Argentina TEDUCAustralia - Buenos Aires [email protected] 25 de Mayo 252 2-B Vicente Lopez Provincia de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Argentina Latino Australia Education - Mendoza [email protected] 54 261 439 0478 R. Obligado 37 - Oficina S3 Godoy Cruz Mendoza Argentina Bada Education Centre - Canberra [email protected] 61 2 6262 6969 Room 1, 175 City walk, Canberra city Canberra ACT 2601 Australia KOKOS International - Canberra [email protected] 61 2 6247 1658 Suite 1, 134 Bunda Street Canberra -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•... -

The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): an Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2003 The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Terrance Gerard Galvin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, European History Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Galvin, Terrance Gerard, "The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment" (2003). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 996. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Abstract In examining select works of English architects Joseph Michael Gandy and Sir John Soane, this dissertation is intended to bring to light several important parallels between architectural theory and freemasonry during the late Enlightenment. Both architects developed architectural theories regarding the universal origins of architecture in an attempt to establish order as well as transcend the emerging historicism of the early nineteenth century. There are strong parallels between Soane's use of architectural narrative and his discussion of architectural 'model' in relation to Gandy's understanding of 'trans-historical' architecture. The primary textual sources discussed in this thesis include Soane's Lectures on Architecture, delivered at the Royal Academy from 1809 to 1836, and Gandy's unpublished treatise entitled the Art, Philosophy, and Science of Architecture, circa 1826.