Plant Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunol Wildflower Guide

Sunol Wildflowers A photographic guide to showy wildflowers of Sunol Regional Wilderness Sorted by Flower Color Photographs by Wilde Legard Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District Revision: February 23, 2007 More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. The selection of showy wildflowers displayed in this guide is by no means complete. The intent is to expand the quality and quantity of photos over time. The revision date is shown on the cover and on the header of each photo page. A comprehensive plant list for this area (including the many species not found in this publication) can be downloaded at the East Bay Regional Park District’s wild plant download page at: http://www.ebparks.org. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format to accommodate these planned updates. You have permission to freely download and distribute, and print this pdf for individual use. You are not allowed to sell the electronic or printed versions. In this version of the guide, only showy wildflowers are included. These wildflowers are sorted first by flower color, then by plant family (similar flower types), and finally by scientific name within each family. Under each photograph are four lines of information, based on the current standard wild plant reference for California: The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993. Common Name These non-standard names are based on Jepson and other local references. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

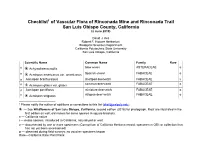

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

Decades of Native Bee Biodiversity Surveys at Pinnacles National Park Highlight the Importance of Monitoring Natural Areas Over Time

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All PIRU Publications Pollinating Insects Research Unit 1-17-2019 Decades of Native Bee Biodiversity Surveys at Pinnacles National Park Highlight the Importance of Monitoring Natural Areas Over Time Joan M. Meiners University of Florida Terry L. Griswold Utah State University Olivia Messinger Carril Independent Researcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/piru_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meiners JM, Griswold TL, Carril OM (2019) Decades of native bee biodiversity surveys at Pinnacles National Park highlight the importance of monitoring natural areas over time. PLoS ONE 14(1): e0207566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0207566 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pollinating Insects Research Unit at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All PIRU Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESEARCH ARTICLE Decades of native bee biodiversity surveys at Pinnacles National Park highlight the importance of monitoring natural areas over time 1 2 3 Joan M. MeinersID *, Terry L. Griswold , Olivia Messinger Carril 1 School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, United States of a1111111111 America, 2 USDA-ARS Pollinating Insects Research Unit (PIRU), Utah State University, Logan, Utah, United States of America, 3 Independent Researcher, Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Thousands of species of bees are in global decline, yet research addressing the ecology OPEN ACCESS and status of these wild pollinators lags far behind work being done to address similar impacts on the managed honey bee. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 25 / Thursday, February 6, 1997 / Rules and Regulations

5542 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 25 / Thursday, February 6, 1997 / Rules and Regulations effective competitive opportunities test deemed granted as of the 28th day recreational activities, mining, road in § 63.18(h)(6)(i) of this chapter has without any formal staff action being construction and maintenance, a flood been satisfied on the route covered by taken: provided control project, and other human the alternative settlement arrangement; (1) The petition is not formally impacts. Potential threats include or opposed within the meaning of herbicide application to control (ii) The effective competitive § 1.1202(e) of this chapter; and herbaceous and weedy taxa. This rule opportunities test in § 63.18(h)(6)(i) of (2) The International Bureau has not implements the Federal protection and this chapter is satisfied on the route notified the filing carrier that grant of recovery provisions afforded by the Act covered by the alternative settlement the petition may not serve the public for these species. arrangement; or interest and that implementation of the EFFECTIVE DATE: March 10, 1997. (iii) The alternative settlement proposed alternative settlement ADDRESSES: The complete file for this arrangement is otherwise in the public arrangement must await formal staff interest. rule is available for public inspection, action on the petition. If objections or by appointment, during normal business (2) A certification as to whether the comments are filed, the petitioning alternative settlement arrangement hours at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife carrier may file a response pursuant to Service, Sacramento Field Office, 3310 affects more than 25 percent of the § 1.45 of this chapter. -

Table of Contents Page

BIOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY FOR WOODVILLE PUBLIC UTILITY DISTRICT’S WATER WELL REPLACEMENT PROJECT ( NEAR WOODVILLE, TULARE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA ) Prepared for Woodville Public Utility District P.O. Box 4567 16716 Avenue 168 Woodville, CA 93258 (559) 686-9649 September 2019 Prepared by HALSTEAD & ASSOCIATES Environmental / Biological Consultants 296 Burgan Avenue, Clovis, CA 93611 Office (559) 298-2334; Mobile (559) 970-2875 Fax (559) 322-0769; [email protected] Table of Contents Page 1. Summary ..............................................................................................................................1 2. Background ..........................................................................................................................2 3. Project Location ...................................................................................................................2 4. Project Description...............................................................................................................2 5. Project Site Description .......................................................................................................2 6. Regulatory Overview ...........................................................................................................3 7. Survey Methods ...................................................................................................................7 8. Wildlife Resources in the Project Area ................................................................................8 -

Vascular Flora of the Liebre Mountains, Western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 15 1999 Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Steve (1999) "Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol18/iss2/15 Aliso, 18(2), pp. 93-139 © 1999, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 VASCULAR FLORA OF THE LIEBRE MOUNTAINS, WESTERN TRANSVERSE RANGES, CALIFORNIA STEVE BOYD Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 N. College Avenue Claremont, Calif. 91711 ABSTRACT The Liebre Mountains form a discrete unit of the Transverse Ranges of southern California. Geo graphically, the range is transitional to the San Gabriel Mountains, Inner Coast Ranges, Tehachapi Mountains, and Mojave Desert. A total of 1010 vascular plant taxa was recorded from the range, representing 104 families and 400 genera. The ratio of native vs. nonnative elements of the flora is 4:1, similar to that documented in other areas of cismontane southern California. The range is note worthy for the diversity of Quercus and oak-dominated vegetation. A total of 32 sensitive plant taxa (rare, threatened or endangered) was recorded from the range. Key words: Liebre Mountains, Transverse Ranges, southern California, flora, sensitive plants. INTRODUCTION belt and Peirson's (1935) handbook of trees and shrubs. Published documentation of the San Bernar The Transverse Ranges are one of southern Califor dino Mountains is little better, limited to Parish's nia's most prominent physiographic features. -

Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/300 ON THE COVER Common salsify (Tragopogon dubius) was one of the most widespread exotic plant species found in the monument during this inventory. Photograph by: Safiya Jetha Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/300 Julie E. Korb Biology Department Fort Lewis College 1000 Rim Drive Durango, CO 81301 March 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural re- source topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientif- ically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Views, statements, findings, conclusions, recommendations, and data in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views and policies of the National Park Service, U.S. -

A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.14 In Memory of Rebecca Ciresa Wenk, Botaness ON THE COVER Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park Photography by: Brent Paull A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.14 Ann Huber University of California Berkeley 41043 Grouse Drive Three Rivers, CA 93271 Adrian Das U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center, Sequoia-Kings Canyon Field Station 47050 Generals Highway #4 Three Rivers, CA 93271 Rebecca Wenk University of California Berkeley 137 Mulford Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-3114 Sylvia Haultain Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks 47050 Generals Highway Three Rivers, CA 93271 June 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. -

Phylogenies and Secondary Chemistry in Arnica (Asteraceae)

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 392 Phylogenies and Secondary Chemistry in Arnica (Asteraceae) CATARINA EKENÄS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 UPPSALA ISBN 978-91-554-7092-0 2008 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-8459 !"# $ % !& '((" !()(( * * * + , - . , / , '((", + 0 1# 2, # , 34', 56 , , 70 46"84!855&86(4'8(, - 1# 2 . * 9 10-2 . * . # 9 , * * 1 ! " #! !$ 2 1 2 .8 # * * :# 77 1%&'(2 . !6 '3, + . .8 ) / , ; < * . * ** # , * * * , 09 * . # * * 33 * != , 0- # 9 * * 1, , * 2 . * , 0 * * * * * . * , $ * 0- * % # , # 8 * * * * * * $8> # . * * !' , * * . ** , ? . 0- , +,- # # 7-0 -0 :+' 9 +# $8> ./0) . ) 1 ) 2 * 3) ) .456(7 ) , @ / '((" 700 !=5!8='!& 70 46"84!855&86(4'8( ) ))) 8"&54 1 );; ,/,; A B ) ))) 8"&542 List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I Ekenäs, C., B. G. Baldwin, and K. Andreasen. 2007. A molecular phylogenetic