Thesis (PDF, 797.1KB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brno Studies in English Volume 39, No. 2, 2013 ISSN 0524-6881 DOI: 10.5817/BSE2013-2-8

Brno Studies in English Volume 39, No. 2, 2013 ISSN 0524-6881 DOI: 10.5817/BSE2013-2-8 ANDRÉ LOISELLE CANADIAN HORROR, AMERICAN BODIES: CORPOREAL OBSESSION AND CULTURAL PROJECTION IN AMERICAN NIGHTMARE, AMERICAN PSYCHO, AND AMERICAN MARY Abstract Many Canadian horror films are set in the United States and claim to provide a graphic critique of typically American social problems. Using three made-in- -Canada films that explicitly situate themselves “south of the border,” – Ame- rican Nightmare“ (1983, Don McBrearty), “American Psycho” (2000, Mary Harron), and “American Mary” (2012, Jen Soska and Sylvia Soska) – this essay argues that these and other similar cinematic tales of terror have less to do with America than with Canada’s own national anxieties. These films project Ca- nadian fears onto the United States to avoid facing our national implication in horror, mayhem and chaos; and more often than not, the body is the preferred site of such projection. In this way, such films unwittingly expose Canada’s dark obsessions through cultural displacement. Ultimately, this article suggest that Canadians have a long way to go before they can stop blaming the American monster for everything bad that happens to them, and finally dare to embrace their own demons. Key words Canadian horror films; the body as site of terror; Imaginary Canadian; Cana- da-US relationship; Toronto and Vancouver masquerading as American cities Canadian comedian Martin Short was once asked by American late-night TV show host David Letterman what is the difference between the inhabitants of the two neighboring nations. In what is probably the most accurately pithy answer to this eternal question, Short wittily replied, “Americans watch TV, Canadians watch American TV” (Pevere 1998: 10). -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

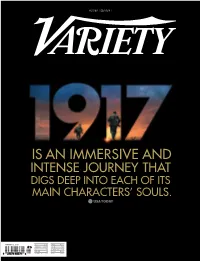

Is an Immersive and Intense Journey That Digs Deep Into Each of Its Main Characters’ Souls

ADVERTISEMENT IS AN IMMERSIVE AND INTENSE JOURNEY THAT DIGS DEEP INTO EACH OF ITS MAIN CHARACTERS’ SOULS. JANUARY 2, 2020 US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1280 CANADA $11.99 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG $95 EUROPE €9 RUSSIA 400 AUSTRALIA $14 INDIA 800 3 GOLDEN GLOBE® NOMINATIONS INCLUDING DRAMA BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARDS NOMINATIONS INCLUDING 8 BEST DIRECTOR BEST PICTURE SAM MENDES THE BEST OF THE LIKE NO FILM YOU A MASTERWORK OF PICTURE YEAR IS HAVE SEEN. THE FIRST ORDER. YOU COULDN’T LOOK AWAY IF YOU WANTED TO. GOLDEN GLOBES YEARS HER MOMENT FOLLOWING ACCLAIMED ROLES IN ‘BOMBSHELL’ AND ‘ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD,’ ACTOR-PRODUCER MARGOT ROBBIE STORMS THE NEW YEAR WITH A FLURRY OF CREATIVE ENDEAVORS BY KATE AURTHUR P.5 0 P.50 Hollywood on Her Terms Margot Robbie is charging ahead as both an actor and a producer, carving a path for other women along the way. By KATE AURTHUR P.58 Creative Champion AMC Networks programming chief Sarah Barnett competes with streamers by nurturing creators of new cultural hits. By DANIEL HOLLOWAY P.62 Variety Digital Innovators 2020 Twelve leading minds in tech and entertainment are honored for pushing content boundaries. By TODD SPANGLER and JANKO ROETTGERS HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE SCARLETT/THE WALL GROUP/MOROCCAN OIL; MANICURE: TOM BACHIK; DRESS: CHANEL BACHIK; OIL; MANICURE: TOM GROUP/MOROCCAN WALL SCARLETT/THE HANEL; HAIR: BRYCE VARIETY.COM JANUARY 2, 2020 JANUARY (COVER AND THIS PAGE) PHOTOGRAPHS BY ART STREIBER; WARDROBE: KATE YOUNG/THE WALL GROUP; MAKEUP: PATI DUBROFF/FORWARD ARTISTS/C -

Spartan Daily (October 5, 2011)

Happiness does not come with a price tag Opinion p. 5 See online: Wednesday SPARTAN DAILY LibraryLib evacuated October 5, 2011 Hornets swarm Spartans Sports p. 4 Volume 137, Issue 21 SpartanDaily.com Increasing SJ gang A Clean Slate activity prompts UPD campus alert Over the past 18 months, San Jose has Crimes increase south of seen a spike in gang activity. campus; police cite regular “There have always been spikes in gang activities,” Sgt. Manuel fluctuation in frequency Aguayo of the UPD said. “It’s a generational thing … it's cyclical.” by Chris Marian Staff Writer Homicides per 3.5 100,000 people per year On the night of Saturday, Sept. 24, in San Jose residents of the 500 block of South 3.0 All homicides 10th Street awoke to the sounds of gunfi re ringing out into the night, as 2.5 police said rival gangs clashed once 2.0 more for territory and respect in the neighborhoods southwest of the SJSU 1.5 campus. Gang-related Police arriving on the scene se- 1.0 cured one wounded suspect and cap- homicides 0.5 tured another — the rest fl ed south 20062007 2008 2009 2010 Dulce Alvarez, a San Jose Conservation Corps intern, The Conservation Corp has been working with the with a San Jose Police Department dumps recyclables into a bin on Wednesday, Sept. 28 City of San Jose to advance its zero-waste policy. SWAT team on their heels, according 80 Gang-related crimes per outside of Clark Hall. Alvarez has been working as a The corps has been in existence since 1987. -

MARCELO EDUARDO MARCHI META-TERROR: O Uso Da Metalinguagem Como Recurso Narrativo No Slasher Movie

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO CARLOS CENTRO DE EDUCAÇÃO E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ARTES E COMUNICAÇÃO MARCELO EDUARDO MARCHI META-TERROR: o uso da metalinguagem como recurso narrativo no slasher movie SÃO CARLOS - SP 2020 MARCELO EDUARDO MARCHI META-TERROR: o uso da metalinguagem como recurso narrativo no slasher movie Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Imagem e Som, da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, para obtenção do título de Mestre em Imagem e Som. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alessandro Constantino Gamo São Carlos-SP 2020 Dedicado aos arquitetos desse fascinante universo que é o gênero terror. Que sua inesgotável imaginação e ousadia estejam sempre grudadas em mim, como o sangue de porco na doce Carrie. AGRADECIMENTOS Nem mesmo as cento e tantas páginas desta dissertação seriam suficientes para expressar minha gratidão às mulheres que, todos os dias, fazem de mim o que eu sou. Elas permanecem zelando para que eu alcance os meus sonhos, e, mais importante ainda, para que eu nunca deixe de sonhar. Minha mãe, Dirce, minhas irmãs, Márcia e Marta, e minha sobrinha, Júlia, amo vocês com todas as minhas forças! Ao meu falecido pai, Benedito: sei que sua energia ainda está conosco. Agradeço também aos meus colegas de mestrado. Tão precioso quanto o conhecimento adquirido nessa jornada é o fato de tê-la compartilhado com vocês. Desejo-lhes um futuro sempre mais e mais brilhante. Aos amigos de tantos anos, obrigado por me incentivarem a abraçar mais essa etapa e por estarem presentes também nos momentos de esfriar a cabeça e jogar conversa fora: Jefferson Galetti e Vanessa Bretas, Dú Marques, Vitão Godoy, Led Bacciotti e Giovana Bueno, Nico Stolzel e Paulinha Gomes, Miller Guglielmo, e a galera da república Alcatraz em São Carlos. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Chapter 1 1. Jeffrey Mirel, “The Traditional High School: Historical Debates over Its Nature and Function,” Education Next 6 (2006): 14–21. 2. US Census Bureau, “Education Summary––High School Gradu- ates, and College Enrollment and Degrees: 1900 to 2001,” His- torical Statistics Table HS-21, http://www.census.gov/statab/ hist/HS-21.pdf. 3. Andrew Monument, dir., Nightmares in Red, White, and Blue: The Evolution of American Horror Film (Lux Digital Pictures, 2009). 4. Monument, Nightmares in Red. Chapter 2 1. David J. Skal, Screams of Reason: Mad Science and Modern Cul- ture (New York: Norton, 1998), 18–19. For a discussion of this more complex image of the mad scientist within the context of postwar film science fiction comedies, see also Sevan Terzian and Andrew Grunzke, “Scrambled Eggheads: Ambivalent Represen- tations of Scientists in Six Hollywood Film Comedies from 1961 to 1965,” Public Understanding of Science 16 (October 2007): 407–419. 2. Esther Schor, “Frankenstein and Film,” in The Cambridge Com- panion to Mary Shelley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 63; James A. W. Heffernan, “Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (Autumn 1997): 136. 3. Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe (New York: Basic Books, 1987). 4. Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism and American Life (New York: Knopf, 1963); Craig Howley, Aimee Howley, and Edwine D. Pendarvis, Out of Our Minds: Anti-Intellectualism and Talent 178 Notes Development in American Schooling (New York: Teachers Col- lege Press: 1995); Merle Curti, “Intellectuals and Other People,” American Historical Review 60 (1955): 259–282. -

Female Authorship in the Slumber Party Massacre Trilogy

FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY By LYNDSEY BROYLES Bachelor of Arts in English University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 2016 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2019 FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Thesis Approved: Jeff Menne Thesis Adviser Graig Uhlin Lynn Lewis ii Name: LYNDSEY BROYLES Date of Degree: MAY, 2019 Title of Study: FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Major Field: ENGLISH Abstract: The Slumber Party Massacre series is the only horror franchise exclusively written and directed by women. In a genre so closely associated with gender representation, especially misogynistic sexual violence against women, this franchise serves as a case study in an alternative female gaze applied to a notoriously problematic form of media. The series arose as a satire of the genre from an explicitly feminist lesbian source only to be mediated through the exploitation horror production model, which emphasized female nudity and violence. The resulting films both implicitly and explicitly address feminist themes such as lesbianism, trauma, sexuality, and abuse while adhering to misogynistic genre requirements. Each film offers a unique perspective on horror from a distinctly female viewpoint, alternately upholding and subverting the complex gender politics of women in horror films. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 -

2016 and Will Not Have Begun Principal Photography During This Calendar Year

The Black List was compiled from the suggestions of over 250 film executives, each of whom contributed the names of up to ten of her favorite scripts that were written in, or are somehow uniquely associated with, 2016 and will not have begun principal photography during this calendar year. This year, scripts had to receive at least six mentions to be included on the Black List. All reasonable effort has been made to confirm the information contained herein. The Black List apologizes for all misspellings, misattributions, incorrect representation identification, and questionable 2016 affiliations. It has been said many times, but it’s worth repeating: The Black List is not a “best of” list. It is, at best, a “most liked” list. “ The more we’re governed by idiots and have no control over our own destinies, the more we need to tell stories to each other about who we are, why we are, where we come from, and what might be possible. “ ALAN RICKMAN BLOND AMBITION Elyse Hollander In 1980s New York, Madonna struggles to get her first album released while navigating fame, romance, and a music industry that views women as disposal. AGENCY MANAGEMENT PRODUCERS WILLIAM MORRIS ENDEAVOR BELLEVUE PRODUCTIONS RATPAC ENTERTAINMENT, MICHAEL DELUCA PRODUCTIONS, AGENTS MANAGERS BELLEVUE PRODUCTIONS TANYA COHEN,48 SIMON FABER JOHN ZAOZIRNY LIFE ITSELF Dan Fogelman A multigenerational love story that weaves together a number of characters whose lives intersect over the course of decades from the streets of New York to the Spanish countryside and back. AGENCY MANAGEMENT PRODUCERS WILLIAM MORRIS ENDEAVOR MANAGEMENT 360 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, TEMPLE HILL AGENTS MANAGERS FINANCIERS DANNY GREENBERG35ERYN BROWN FILMNATION THE OLYMPIAN Tony Tost The true story of an underdog rower trying to make it into the 1984 Olympics, told through the story of his relationships with his coach, his father, his fiancée, and with competition itself. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Audiobooks Biography Nonfiction

Audiobooks 1st case / James Patterson and Chris Tebbetts.","AUD CD MYS PATTERSON" "White fragility : why it's so hard for white people to talk about racism / Robin DiAngelo.","AUD CD 305.8 DIA" "The guest list : a novel / Lucy Foley, author of The hunting party.","AUD CD FIC FOLEY" Biography "Beyond valor : a World War II story of extraordinary heroism, sacrificial love, and a race against time / Jon Erwin and William Doyle.","B ERWIN" "Chasing the light : writing, directing, and surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and the movie game / Oliver Stone.","B STONE" "Disloyal : a memoir : the true story of the former personal attorney to the President of the United States / Michael Cohen.","B COHEN" Horse crazy : the story of a woman and a world in love with an animal / Sarah Maslin Nir.","B NIR" "Melania and me : the rise and fall of my friendship with the First Lady / Stephanie Winston Wolkoff.","B TRUMP" "Off the record : my dream job at the White House, how I lost it, and what I learned / Madeline Westerhout.","B WESTERHOUT" "A knock at midnight : a story of hope, justice, and freedom / Brittany K. Barnett.","B BARNETT" "The meaning of Mariah Carey / Mariah Carey with Michaela Angela Davis.","B CAREY" "Solutions and other problems / Allie Brosh.","B BROSH" "Doc : the life of Roy Halladay / Todd Zolecki.","B HALLADAY" Nonfiction "Caste : the origins of our discontents / Isabel Wilkerson.","305.512 WIL" "Children of Ash and Elm : a history of the Vikings / Neil Price.","948.022 PRI" "Chiquis keto : the 21-day starter kit for taco, tortilla, and tequila lovers / Chiquis Rivera with Sarah Koudouzian.","641.597 RIV" "Clean : the new science of skin / James Hamblin.","613 HAM" "Do it afraid : embracing courage in the face of fear / Joyce Meyer.","248.8 MEY" "The end of gender : debunking the myths about sex and identity in our society / Dr. -

6 YEARS Written and Directed by Hannah Fidell

! 6 YEARS Written and Directed by Hannah Fidell ! Starring Taissa Farmiga and Ben Rosenfield 80 minutes, color, U.S.A. Sales Contact: ICM/ Jessica Lacy [email protected] / (310) 550-4316 SUBMARINE/ Josh Braun [email protected] / (212) 625-1410 Press Contact: BRIGADE / Gerilyn Shur [email protected] / 917-551-5838 SYNOPSIS A young couple in their early 20s, Dan and Melanie, have known each other since childhood. Now their 6-year romantic relationship is put to the test when Dan receives an attractive job offer from the record label with whom he interns, and he must choose between a move forward and a future with Mel. Growth and temptation happen – but will their relationship remain part of their future? Writer/director Hannah Fidell explores the struggles of young love as it begins to face the next steps into adulthood. Taissa Farmiga and Ben Rosenfield give warm, genuine performances as Mel and Dan, alongside Lindsay Burdge (star of Fidell’s A TEACHER) as a colleague of Dan’s who entices him in more ways than one. HANNAH FIDELL DISCUSSES 6 YEARS I wrote 6 Years focusing on the relationship of two young adults. Who hasn’t had a first love? And who hasn’t gone through a breakup with said first love? (for those of you who are married to that first person...please ignore…) More than anything though, I modeled Dan and Mel’s world on my group of friends in college. Although, the fighting and the physical violence, that was pure fiction. The script was in great hands with Taissa and Ben.