Respondent's Briefon Appeal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Northern Mall North Olmsted, (Cleveland) Ohio a Huge Mall, Just Outside a Resurging City, with Unique-To-Market Retailers: a Sure Recipe for Success

Great Northern Mall Great Northern Mall North Olmsted, (Cleveland) Ohio A huge mall, just outside a resurging city, with unique-to-market retailers: a sure recipe for success. But Great Northern Mall, located on Cleveland’s WESTLAKE, OH CLEVELAND, OH West Side, offers something more. Its diverse anchors, revitalized Dining Court and state-of-the- STRONGSVILLE, OH art cinema create a draw for the region’s families, OBERLIN, OH extending through two counties, who fulfill their AKRON, OH 10 MILES needs and wants on a daily basis. Great Northern has it all. Great Northern Mall North Olmsted, (Cleveland) Ohio • Enclosed single-level super-regional mall • Located 13 miles southwest of downtown Cleveland • Exceptionally large trade area • Near affluent areas of Westlake, Avon, Lakewood, Bay Village, and Rocky River Property Description major roads I-480 and Highway 252 center description Enclosed, one-level center total sf 1,200,000 anchors Macy’s, Dillard’s, JCPenney, Sears, and Dick’s Sporting Goods # of stores 120 key tenants Disney Store, H&M, Justice, Pandora, The Rail, # of parking 5,300 Forever 21, Victoria’s Secret, Pink, New York & Company, and a 10-screen Regal Cinemas THE CENTER THE MARKET STARWOOD Great Northern Mall “Whether you are looking for a new home, place of business or a fun day of shopping, entertainment and a great meal, you will find our community has a lot to offer.” — North Olmsted Mayor Kevin Kennedy THE CENTER THE MARKET STARWOOD Great Northern Mall • At Interstate 480 and State Route 252 • 5 minutes from Cleveland -

To View the 2017 Topps Series 1 Baseball Card

BASE A.J. Ramos Miami Marlins® A.J. Reed Houston Astros® Aaron Altherr Philadelphia Phillies® Aaron Hicks New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Rookie Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Aaron Sanchez Toronto Blue Jays® League Leaders Adam Conley Miami Marlins® Adam Duvall Cincinnati Reds® Adam Eaton Chicago White Sox® Adam Lind Seattle Mariners™ Adam Wainwright St. Louis Cardinals® Addison Russell Chicago Cubs® World Series Highlight Addison Russell Chicago Cubs® Adeiny Hechavarria Miami Marlins® Adonis Garcia Atlanta Braves™ Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® Adrian Gonzalez Los Angeles Dodgers® Albert Pujols Angels® League Leaders Alcides Escobar Kansas City Royals® Aledmys Diaz St. Louis Cardinals® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® Rookie Alex Colome Tampa Bay Rays™ Alex Reyes St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie Alex Wood Los Angeles Dodgers® Andre Ethier Los Angeles Dodgers® Andrew Benintendi Boston Red Sox® Rookie Andrew Cashner Miami Marlins® Angel Pagan San Francisco Giants® Angels Angels® Anibal Sanchez Detroit Tigers® Anthony DeSclafani Cincinnati Reds® Anthony Gose Detroit Tigers® Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® League Leaders Archie Bradley Arizona Diamondbacks® Arizona Diamondbacks Arizona Diamondbacks® Arodys Vizcaino Atlanta Braves™ Aroldis Chapman Chicago Cubs® World Series Highlight Asdrubal Cabrera New York Mets® Austin Jackson Chicago White Sox® B'More Boppers Baltimore Orioles® Combo Card Baltimore Orioles Baltimore Orioles® Ben Revere Washington Nationals® Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® Big Fish Miami Marlins® Combo Card Billy Butler New York Yankees® Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ Braden Shipley Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® Brandon Finnegan Cincinnati Reds® Brandon Guyer Cleveland Indians® Brandon Moss St. Louis Cardinals® Brett Lawrie Chicago White Sox® Brian Goodwin Washington Nationals® Rookie Brian McCann New York Yankees® Bryce Harper Washington Nationals® Byron Buxton Minnesota Twins® C.J. -

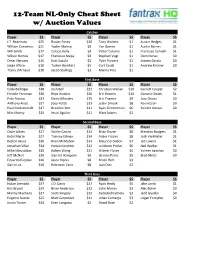

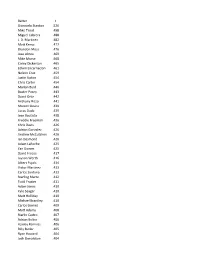

PDF Cheat Sheet

12-Team NL-Only Cheat Sheet w/ Auction Values Catcher Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ J.T. Realmuto $25 Buster Posey $10 Tony Wolters $1 Austin Hedges $1 Willson Contreras $21 Yadier Molina $9 Yan Gomes $1 Austin Barnes $1 Will Smith $17 Carson Kelly $9 Victor Caratini $1 Francisco Cervelli $1 Wilson Ramos $17 Francisco Mejia $9 Stephen Vogt $1 Dom Nunez $0 Omar Narvaez $16 Kurt Suzuki $5 Tyler Flowers $1 Aramis Garcia $0 Jorge Alfaro $10 Tucker Barnhart $5 Curt Casali $1 Andrew Knizner $0 Travis d'Arnaud $10 Jacob Stallings $1 Manny Pina $1 First Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Cody Bellinger $38 Josh Bell $22 Christian Walker $10 Garrett Cooper $2 Freddie Freeman $36 Rhys Hoskins $20 Eric Hosmer $10 Dominic Smith $1 Pete Alonso $32 Daniel Murphy $15 Eric Thames $9 Jose Osuna $0 Anthony Rizzo $27 Joey Votto $13 Justin Smoak $8 Kevin Cron $0 Paul Goldschmidt $27 Brandon Belt $11 Ryan Zimmerman $6 Yonder Alonso $0 Max Muncy $25 Jesus Aguilar $11 Matt Adams $2 Second Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Ozzie Albies $27 Starlin Castro $14 Brian Dozier $8 Brendan Rodgers $1 Ketel Marte $27 Tommy Edman $14 Adam Frazier $8 Josh VanMeter $1 Keston Hiura $26 Ryan McMahon $14 Mauricio Dubon $7 Jed Lowrie $1 Jonathan Villar $24 Howie Kendrick $12 Jurickson Profar $6 Neil Walker $1 Mike Moustakas $20 Kolten Wong $11 Wilmer Flores $5 Yolmer Sanchez $0 Jeff McNeil $19 Garrett Hampson $9 Hernan Perez $5 Brad Miller $0 Eduardo Escobar $16 Jason Kipnis $8 Brock Holt $3 Gavin Lux $16 Robinson Cano $8 Isan Diaz $2 Third Base Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Player $$ Nolan Arenado $37 J.D. -

2018 Topps Series 1 Checklist Finala

2018 TOPPS BASEBALL SERIES 1 BASE CARDS A.J. Pollock Arizona Diamondbacks® A.J. Ramos New York Mets® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® League Leaders Aaron Judge New York Yankees® League Leaders Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Aaron Sanchez Toronto Blue Jays® Aaron Slegers Minnesota Twins® Rookie Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adam Wainwright St. Louis Cardinals® Adeiny Hechavarria Tampa Bay Rays™ Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® Aledmys Diaz St. Louis Cardinals® Alex Avila Chicago Cubs® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® World Series Highlights Alex Colome Tampa Bay Rays™ Alex Verdugo Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie Alex Wood Los Angeles Dodgers® Amed Rosario New York Mets® Rookie American League™ American League™ Combo Cards Amir Garrett Cincinnati Reds® Andrelton Simmons Angels® Andrew Cashner Texas Rangers® Andrew McCutchen Pittsburgh Pirates® Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® Andrew Stevenson Washington Nationals® Rookie Anthony Banda Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® Antonio Senzatela Colorado Rockies™ Ariel Miranda Seattle Mariners™ Austin Hays Baltimore Orioles® Rookie Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® League Leaders Billy Hamilton Cincinnati Reds® Boston Red Sox® Boston Red Sox® Combo Cards Brad Hand San Diego Padres™ Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Drury Arizona Diamondbacks® Brandon Finnegan Cincinnati Reds® Brandon McCarthy Los Angeles Dodgers® Brandon Phillips Angels® Brandon Woodruff -

Daniel Murphy National League Mvp Candidate 2016 National League All-Star

DANIEL MURPHY NATIONAL LEAGUE MVP CANDIDATE 2016 NATIONAL LEAGUE ALL-STAR LEADING MAN Nationals second baseman Daniel Murphy leads, or ranks near the top of the National League in a majority of offensive categories, including: STATISTIC NUMBER NL RANK THE COMPETITION Slugging Percentage .596 1st Here is a look at how Daniel Murphy compares to the other National League Most OPS .987 1st Valuable Player candidates: Doubles 47 1st NAME AVG R HR RBI XBH BB SO OBP SLG OPS Batting Average .347 2nd D. Murphy .347 88 25 104 77 35 57 .391 .596 .987 Go-Ahead RBI 31 2nd N. Arenado .293 112 40 129 79 66 100 .361 .571 .932 Plate Appearances/Strikeout 10.19 2nd K. Bryant .295 120 39 101 77 74 151 .389 .564 .953 Strikeout Percentage 9.8% 2nd A. Rizzo .293 91 31 105 78 74 104 .388 .548 .936 Multi-hit games 56 3rd RBI 104 T3rd CONTROL + SHIFT Extra Base Hits 77 T4th Hits 184 4th According to Baseball Info Solutions (BIS), Daniel Murphy has been incredibly Total Bases 316 5th successful against defensive shifts, demonstrating his ability to adjust when faced with this potential opposition advantage. As of Sept. 22, Murphy is hitting .368 on FANGRAPHS SAYS... NUMBER NL RANK Grounders and Short Liners (GSL) when the defense shifts, just 13 points lower Weighted On-Base Average .409 T1st than when there is not a shift. He’s hitting .381 when not shifted on a GSL. ***Measures offensive value by weighting each aspect of hitting in proportion to their actual run value*** • This number reflects batting average on those balls put in play and doesn’t in- Weighted Runs Created+ 156 T1st clude strikeouts or the quality of those hits. -

MTA Report January 2006

myMetro.net: Archives January 2006 Home CEO Hotline Viewpoint News Releases Archives Metro.net (web) myMetro.net archives | Articles from January 2006 Resources Tuesday, January 31 Safety Metro’s Arthur Winston Signs Final Retirement Papers Pressroom (web) Major Emergency Rescue Exercise in Eastside Tunnel CEO Hotline Memorial Service Scheduled for Storekeeper Larry Magee Metro Projects Friday, January 27 Facts at a Glance Management, Labor Hope New Bargaining Process Will Smooth 2006 Negotiations Archives Metro Begins Last Street Decking for Eastside Tunnel Portal Events Calendar Thursday, January 26 Research Center/ December Shake-up Was Biggest Job for Stops and Zones Since 2003 Library Deputy’s Routine Traffic Stop Nets Drugs and $12,202 in Cash Metro Cafe (pdf) Wednesday, January 25 Metro Classifieds 3 New 2550 Light Rail Cars in Transit to California Retirement Division 18 Operator Lakeisha Francois is a Low Rider with a Cause Round-up Division 9 Celebrates ‘How You Doin’?’ Victory Metro Info Metro Co-sponsored Kingdom Day Parade Breakfast Strategic Plan (pdf) Tuesday, January 24 Org Chart (pdf) Governor, Mayor Call for Billions in Transportation Funding Policies Division 9 Tries Seat Adjustment Training to Avoid Back Injuries Training Friday, January 20 Help Desk 2nd Annual Metro Family Day Set for Disneyland, April 8 Limited Stop Service Begins on Metro Gold Line, Feb. 13 Intranet Policy 70s Pop Star Nabbed at Metro Rail Station; Faces Drug Charge Need e-Help? Thursday, January 19 Call the Help Desk at 2-4357 Former LAUSD Clerk Charged with Embezzling from Metro Increase in LA Transit Ridership Beats National Averages E-Mail Webmaster NoHo Theater Scene Featured in Metro’s Latest Neighborhood Poster Wednesday, January 18 New Electronic Payroll System Gives Employees Control Six Selected as Employees of the Quarter for 1st Quarter FY 2006 PriceWaterhouseCoopers Exec Speaks to NCMA Chapter Friday, January 13 CEO UpDate> Neither Wind nor Rain Could Stop Metro as 2006 Begins Expo Authority Board Approves $640 Mill. -

APBA Pro Baseball 2015 Carded Player List

APBA Pro Baseball 2015 Carded Player List ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CINCINNATI COLORADO LOS ANGELES Ender Inciarte Jace Peterson Dexter Fowler Billy Hamilton Charlie Blackmon Jimmy Rollins A. J. Pollock Cameron Maybin Jorge Soler Joey Votto Jose Reyes Howie Kendrick Paul Goldschmidt Freddie Freeman Kyle Schwarber Todd Frazier Carlos Gonzalez Justin Turner David Peralta Nick Markakis Kris Bryant Brandon Phillips Nolan Arenado Adrian Gonzalez Welington Castillo Adonis Garcia Anthony Rizzo Jay Bruce Ben Paulsen Yasmani Grandal Yasmany Tomas Nick Swisher Starlin Castro Brayan Pena Wilin Rosario Andre Ethier Jake Lamb A.J. Pierzynski Chris Coghlan Ivan DeJesus D.J. LeMahieu Yasiel Puig Chris Owings Christian Bethancourt Austin Jackson Eugenio Suarez Nick Hundley Scott Van Slyke Aaron Hill Andrelton Simmons Miguel Montero Tucker Barnhart Michael McKenry Alex Guerrero Nick Ahmed Michael Bourn David Ross Skip Schumaker Brandon Barnes Kike Hernandez Tuffy Gosewisch Pedro Ciriaco Addison Russell Zack Cozart Justin Morneau Carl Crawford Jarrod Saltalamacchia Daniel Castro Jonathan Herrera Kris Negron Kyle Parker Joc Pederson Jordan Pacheco Hector Olivera Javier Baez Jason Bourgeois Daniel Descalso A. J. Ellis Brandon Drury Eury Perez Chris Denorfia Brennnan Boesch Rafael Ynoa Chase Utley Phil Gosselin Todd Cunningham Matt Szczur Anthony DeSclafani Corey Dickerson Corey Seager Rubby De La Rosa Shelby Miller Jake Arrieta Michael Lorenzen Kyle Kendrick Clayton Kershaw Chase Anderson Julio Teheran Jon Lester Raisel Iglesias Jorge De La Rosa Zack Greinke Jeremy Hellickson Williams Perez Dan Haren Keyvius Sampson Chris Rusin Alex Wood Robbie Ray Matt Wisler Kyle Hendricks John Lamb Chad Bettis Brett Anderson Patrick Corbin Mike Foltynewicz Jason Hammel Burke Badenhop Eddie Butler Mike Bolsinger Archie Bradley Eric Stults Tsuyoshi Wada J. -

Dixie Youth Baseball AAA World Series Records 1998

Dixie Youth Baseball AAA World Series Records 1998 - 2019 Individual Batting - Game (2014) Forrest Gunnison, Fairhope, AL Strikeouts - 14 Hits - 5 Runs Scored - 15 (1998) Cullen Tatum, Hattiesburg, MS (2003) Colin Bray, Pascagoula, MS (2013) Jarrett Elmore, Hartsville, SC Consecutive Strikeouts - 10 (2009) Parker Chavers, AUM Gold, Montgomery, AL RBI’s - 23 (1998) Cullen Tatum, Hattiesburg, MS Doubles - 3 (2007) Tyler Romanik, Dentsville, SC No Hit, No Run Games - 1 (2001) Andrew Jordan, Taylorsville, MS Stolen Bases - 5 (2002) Casey Barefoot, Hartsville, SC (4 innings) (2003) Justin Thomas, Montgomery, AL (1998) Meko Brown, Moss Point, MS (2002) Evan Holder, Ben Simon and Austin White, (2003) Colin Bray, Pascagoula, MS Sacrifices - 4 Montgomery AUM, AL (2004) Tony Fulco, Bossier City, LA (2001) Curtis Fabrizi, Bartow, FL (2010) Wade Beasley & Jaden Hill, Ashdown, AR (2010) Gabriel Dorsey, Bushnell, FL Hit By Pitch - 4 (2010) Cornellius Patterson, Matthew Tadlock & (2014) Ty Suggs, Florence, SC (2009) Dylan Johnson, Troup County, GA Diego Arredondo, Bushnell, FL (2016) Bryce Payne, Nacogdoches, TX Base On Balls - 10 (2017) Raymond Groetsch,Brandon Higgins, Micahel (2016) Cermodrick Bland, Nacogdoches, TX (1999) Drew Youngs, Amherst, VA Rizzuto, Spring Hill, FL Triples - 2 Consecutive Hits - 10 Perfect Game - 1 (2010) Nathan Eastburn, Bushnell, FL (2001) Creighton Quinn, Hilton Head, SC (2000) Casey Barefoot, Hartsville, SC (4 innings) (2016) Lodan Andrei, Bushnell, FL Individual Batting Average - Series Individual Pitching - Series Home Runs - 3 Three Game Series - .700 Wins - 4 (2010) Zavier Moore, Shreveport, LA (2019) Ryder Blackwood, Summerton, TN 7-10 (2017) Web Barnes, Hartsville, SC (2011) Nick Wells, W. Seminole, FL Four Game Series - .750 Strikeouts - 25 (2015) John Malone, Fairhope, AL (2016) Gabe Dapuyen, Dunn, NC 6-8 (2005) Taytom Barnes, Troy, AL Grand Slam Home Runs - 1 Five Game Series - .769 Team Pitching - Game (2001) Cameron Crawford, N. -

Exhibit 1 MILLS ACT AGREEMENT 2042 North Victoria Drive Santa Ana, CA 92706

MILLS ACT AGREEMENT 2042 North Victoria Drive Santa Ana, CA 92706 RECORDING REQUESTED BY AND WHEN RECORDED MAIL TO: City of Santa Ana 20 Civic Center Plaza (M-30) Santa Ana, CA 92702 Attn: Clerk of the Council FREE RECORDING PURSUANT TO GOVERNMENT CODE § 27383 _________________________________________________________________________ HISTORIC PROPERTY PRESERVATION AGREEMENT This Historic Property Preservation Agreement (“Agreement”) is made and entered into by and between the City of Santa Ana, a charter city and municipal corporation duly organized and existing under the Constitution and laws of the of the State of California (hereinafter referred to as “City”), and Andres Matzkin and Lynda Matzkin, husband and wife as Community Property with Right of Survivorship, (hereinafter collectively referred to as “Owner”), owner of real property located at 2042 North Victoria Drive, Santa Ana, California, in the County of Orange and listed on the Santa Ana Register of Historical Properties. RECITALS A. The City Council of the City of Santa Ana is authorized by California Government Code Section 50280 et seq. (known as the “Mills Act”) to enter into contracts with owners of qualified historical properties to provide for appropriate use, maintenance, rehabilitation and restoration such that these historic properties retain their historic character and integrity. B. The Owner possesses fee title in and to that certain qualified real property together with associated structures and improvements thereon, located at 2042 North Victoria Drive, Santa Ana, CA, 92706 and more particularly described in Exhibit “A,” attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference, and hereinafter referred to as the “Historic Property”. C. The Historic Property is officially designated on the Santa Ana Register of Historical Properties pursuant to the requirements of Chapter 30 of the Santa Ana Municipal Code. -

Batter I Giancarlo Stanton .526 Mike Trout .498 Miguel Cabrera .488 J

Batter I Giancarlo Stanton .526 Mike Trout .498 Miguel Cabrera .488 J. D. Martinez .482 Matt Kemp .477 Brandon Moss .476 Jose Abreu .469 Mike Morse .468 Corey Dickerson .465 Edwin Encarnacion .461 Nelson Cruz .459 Justin Upton .454 Chris Carter .454 Marlon Byrd .446 Buster Posey .443 David Ortiz .442 Anthony Rizzo .441 Marcell Ozuna .439 Lucas Duda .439 Jose Bautista .438 Freddie Freeman .436 Khris Davis .426 Adrian Gonzalez .426 Andrew McCutchen .426 Ian Desmond .426 Adam LaRoche .425 Yan Gomes .425 David Freese .417 Jayson Werth .416 Albert Pujols .414 Victor Martinez .413 Carlos Santana .413 Starling Marte .412 Todd Frazier .411 Adam Jones .410 Kyle Seager .410 Matt Holliday .410 Michael Brantley .410 Carlos Gomez .409 Matt Adams .408 Starlin Castro .407 Adrian Beltre .406 Hanley Ramirez .406 Billy Butler .405 Ryan Howard .404 Josh Donaldson .404 Kole Calhoun .400 Russell Martin .400 Anthony Rendon .400 Chase Headley .399 Mark Teixeira .399 Yoenis Cespedes .398 Yasiel Puig .397 Christian Yelich .394 Dexter Fowler .394 Nolan Arenado .393 Joe Mauer .392 Torii Hunter .390 Garrett Jones .389 David Wright .389 Nick Castellanos .388 Jhonny Peralta .388 Justin Morneau .387 Lonnie Chisenhall .386 Seth Smith .386 Jon Jay .385 Luis Valbuena .385 Chris Johnson .385 Evan Longoria .384 Robinson Cano .383 Pablo Sandoval .382 Yadier Molina .382 Jacoby Ellsbury .380 Ryan Braun .379 Daniel Murphy .379 Salvador Perez .378 Alex Gordon .377 Aramis Ramirez .376 Jay Bruce .376 Trevor Plouffe .375 Alex Rios .374 Howie Kendrick .374 Jason Castro .373 Martin Prado .372 Curtis Granderson .372 Jonathan Lucroy .371 Josh Harrison .371 Hunter Pence .371 James Loney .371 Brian Dozier .371 Brett Gardner .371 Asdrubal Cabrera .369 Dioner Navarro .368 Travis d'Arnaud .368 Eric Hosmer .367 Dayan Viciedo .367 Wilin Rosario .367 Neil Walker .366 Melky Cabrera .366 Nick Markakis .365 Scooter Gennett .365 Eduardo Escobar .364 Brandon Phillips .364 Carlos Beltran .364 Miguel Montero .363 Matt Carpenter .361 Denard Span .361 B. -

Padding the Stats: a Study of MLB Player Performance in Meaningless Game- Situations

Padding the Stats: A Study of MLB Player Performance in Meaningless Game- Situations Evan Hsia1, Jaewon Lee2 and Anton T. Dahbura3 Department of Computer Science Johns Hopkins University Abstract This paper presents the concept of Meaningless Game-Situations (MGS) in Major League Baseball (MLB), defined as situations in which a team has a 95% chance or greater of winning the game given the score at that particular inning in the game. We determine the run differentials for each inning that yield a 95% chance or greater of winning the game based on 2013-2016 MLB statistics and look at individual batter performances under MGS. We argue that including a split for MGS in major baseball statistical references should be considered. I. Introduction Hope springs eternal, especially in the game of baseball. But should it? Perhaps the absence of a game clock in baseball, unlike other major sports, creates the illusion that anything is possible, and in particular that one’s team can overcome even the largest of deficits, even late in the game. And, indeed, significant comebacks from behind are possible, but are so unlikely that in some cases they’re considered to be historic. For instance, in the game between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Philadelphia Phillies on June 8, 1989 the Pirates scored 10 runs in the top of the first inning. The Pirates’ radio broadcaster, Jim Rooker, proclaimed that if the Phillies were to come back from the 10-run deficit he would “walk home”. As fate would have it, the Phillies ended up winning the game 15-11, prompting Mr. -

GC 1002 Del Valle Family Papers

GC 1002 Del Valle Family Papers Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1789 – 1929, undated, bulk is 1830 – 1900 Extent: Boxes: 13 legal, 2 ov, 1 mc drawer Language: English and Spanish Abstract: Papers relating to Antonio Seferino del Valle, his son Ygnacio, grandson Reginaldo F., and other family members. Activities include their cattle ranching and wine businesses, particularly in Rancho San Francisco and Rancho Camulos, located in today’s Ventura County, California. Other papers include the political activities of Ygnacio and Reginaldo F. Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Preferred Citation: Del Valle Family Papers, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Related Holdings: P-14 Del Valle [Photograph] Collection, 1870s – 1900 GC 1001 Antonio F. Coronel (1817 – 1894) Papers P-157 Antonio Franco Coronel (1817 – 1894) Collection, ca. 1850 – 1900 Seaver Center for Western History Research GC 1002 The History Department’s Material Culture Collection Scope and Content: Correspondence, business papers, legal papers, personal and family papers, memoranda, military documents, and material relating to Antonio Seferino del Valle (1788-1841), who came to California in the Spanish army in 1819; of his son Ygnacio, (1808-80), born in Jalisco, Mexico, who engaged in the cattle and wine businesses and held at various local and state offices in California; of his grandson, Reginaldo Francisco (1854-1938), who was also active in state politics; Ysabel Varela del Valle (Reginaldo’s mother); and other family members.