“Active Measures”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformación Del Significado Del Feminismo. Análisis Del Discurso

Transformación del Significado del Feminismo. Análisis del Discurso Presente en la Marcha del 8 de marzo del 2020 en la Ciudad de Quito Fátima C. Holguín Herrera Facultad de Comunicación Lingüística y Literatura Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Trabajo de Titulación previo a la Obtención del Título de Licenciado(a) en Comunicación con Mención en Periodismo para Radio Prensa y Televisión Bajo la dirección de Dr. Fernando Albán Quito, Ecuador, 2020 1 2 Resumen En el presente trabajo se usa el análisis del discurso, como herramienta de investigación para examinar el discurso presentado en la marcha del ocho de marzo del dos mil veinte. El mismo que tienen que ver un concepto de emancipación ¿qué conlleva este concepto de emancipación? Supone que hay un estado de opresión, subordinación del cual debemos liberarnos, es justamente de este concepto que hace uso, en este caso, el feminismo, aquí analizado; toma la noción de emancipación del sistema opresor que oprimiría a las mujeres, incluso a los hombres, por lo que hay que liberarse de este sistema denominado patriarcado el que estaría inherentemente anclado al neoliberalismo, capitalismo como se menciona. Palabras clave: feminismo, marxismo, ideología, patriarcado, genero, opresión, violencia. 3 Tabla de Contenido INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................... 6 METODOLOGÍA ..................................................................................................................... 8 EL PROBLEMA -

Signature Redacted Certified By: William Fjricchio Professor of Compa Ive Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature Redacted Accepted By

Manufacturing Dissent: Assessing the Methods and Impact of RT (Russia Today) by Matthew G. Graydon B.A. Film University of California, Berkeley, 2008 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2019 C2019 Matthew G. Graydon. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. S~ri' t A Signature red acted Department of Comparative 6/ledia Studies May 10, 2019 _____Signature redacted Certified by: William fJricchio Professor of Compa ive Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Professor of Comparative Media Studies _OF TECHNOLOGY Director of Graduate Studies JUN 1 12019 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES I I Manufacturing Dissent: Assessing the Methods and Impact of RT (Russia Today) by Matthew G. Graydon Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 10, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT The state-sponsored news network RT (formerly Russia Today) was launched in 2005 as a platform for improving Russia's global image. Fourteen years later, RT has become a self- described tool for information warfare and is under increasing scrutiny from the United States government for allegedly fomenting unrest and undermining democracy. It has also grown far beyond its television roots, achieving a broad diffusion across a variety of digital platforms. -

How America Lost Its Mind the Nation’S Current Post-Truth Moment Is the Ultimate Expression of Mind-Sets That Have Made America Exceptional Throughout Its History

1 How America Lost Its Mind The nation’s current post-truth moment is the ultimate expression of mind-sets that have made America exceptional throughout its history. KURT ANDERSEN SEPTEMBER 2017 ISSUE THE ATLANTIC “You are entitled to your own opinion, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” — Daniel Patrick Moynihan “We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” — Daniel J. Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (1961) 1) WHEN DID AMERICA become untethered from reality? I first noticed our national lurch toward fantasy in 2004, after President George W. Bush’s political mastermind, Karl Rove, came up with the remarkable phrase reality-based community. People in “the reality-based community,” he told a reporter, “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality … That’s not the way the world really works anymore.” A year later, The Colbert Report went on the air. In the first few minutes of the first episode, Stephen Colbert, playing his right-wing-populist commentator character, performed a feature called “The Word.” His first selection: truthiness. “Now, I’m sure some of the ‘word police,’ the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna say, ‘Hey, that’s not a word!’ Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. Or what did or didn’t happen. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Articles & Reports

1 Reading & Resource List on Information Literacy Articles & Reports Adegoke, Yemisi. "Like. Share. Kill.: Nigerian police say false information on Facebook is killing people." BBC News. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt- sh/nigeria_fake_news. See how Facebook posts are fueling ethnic violence. ALA Public Programs Office. “News: Fake News: A Library Resource Round-Up.” American Library Association. February 23, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/articles/fake-news-library-round. ALA Public Programs Office. “Post-Truth: Fake News and a New Era of Information Literacy.” American Library Association. Accessed March 2, 2017. http://www.programminglibrarian.org/learn/post-truth- fake-news-and-new-era-information-literacy. This has a 45-minute webinar by Dr. Nicole A. Cook, University of Illinois School of Information Sciences, which is intended for librarians but is an excellent introduction to fake news. Albright, Jonathan. “The Micro-Propaganda Machine.” Medium. November 4, 2018. https://medium.com/s/the-micro-propaganda-machine/. In a three-part series, Albright critically examines the role of Facebook in spreading lies and propaganda. Allen, Mike. “Machine learning can’g flag false news, new studies show.” Axios. October 15, 2019. ios.com/machine-learning-cant-flag-false-news-55aeb82e-bcbb-4d5c-bfda-1af84c77003b.html. Allsop, Jon. "After 10,000 'false or misleading claims,' are we any better at calling out Trump's lies?" Columbia Journalism Review. April 30, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/trump_fact- check_washington_post.php. Allsop, Jon. “Our polluted information ecosystem.” Columbia Journalism Review. December 11, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/cjr_disinformation_conference.php. Amazeen, Michelle A. -

Unified Conspiracy Theory - Rationalwiki

Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory Unified Conspiracy Theory From RationalWiki The Unified Conspiracy Theory is a conspiracy theory, popular with Some dare call it some paranoids, that all of reality is controlled by a single evil entity that has it in for them. It can be a political entity, like "The Illuminati", or a Conspiracy metaphysical entity, like Satan, but this entity is responsible for the creation and management of everything bad. The Church of the SubGenius has adopted this notion as fundamental dogma. Michael Barkun coined the term "superconspiracy" to refer the idea that the world is controlled by an interlocking hierarchy of conspiracies. Secrets revealed! Similarly, Michael Kelly, a neoconservative journalist, coined the term America Under Siege "fusion paranoia" in 1995 to refer to the blending of conspiracy theories CW Leonis of the left with those of the right into a unified conspiratorial Doug Rokke [1] worldview. Guillotine List of conspiracy theories This was played with in the Umberto Eco novel Foucault's Pendulum , in Majestic 12 which the characters make up a conspiracy theory like this...except it Pravda.ru turns out to be true. Shakespeare authorship Society of Jesus Tupac Shakur Contents v - t - e (http://rationalwiki.org /w/index.php?title=Template:Conspiracynav& action=edit) 1 See also 1.1 (In)Famous proponents 2 External links 3 Footnotes See also List of Conspiracy Theories Maltheism Crank magnetism (In)Famous proponents David Icke Alex Jones Lyndon LaRouche Jeff Rense 1 of 2 7/19/2012 8:24 PM Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory External links Flowchart guide to the grand conspiracy (http://farm4.static.flickr.com /3048/2983450505_34b4504302_o.png) Conspiracy Kitchen Sink (http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ConspiracyKitchenSink) , TV Tropes Footnotes 1. -

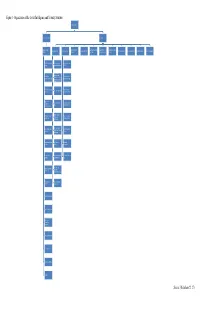

Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure Source

Figure 1- Organization of the Soviet Intelligence and Security Structure General Chairman First Deputy Chairman Chief, GRU Deputy Chairman Space Intelligence Operational/ Technical Administrative/ Directorate for Foreign First Deputy Chief Chief of Information Personnel Directorate Political Department Financial Department Eighth Department Archives Department (KGB) Directorate Directorate Technical Directorate Relations First Chief Directorate First Directorate: Seventh Directorate: (Foreign) Europe and Morocco NATO Second Directorate: North and South Second Chief Eighth Directorate: America, Australia, Directorate (Internal) Individual Countries New Zealand, United Kingdom Fifth Chief Directorate Ninth Directorate: Third Directorate: Asia (Dissidents) Military Technology Eighth Chief Fourth Directorate: Tenth Directorate: Directorate Africa Military Economics (Communications) Fifth Directorate: Chief Border Troops Eleventh Directorate: Operational Directorates Doctrine, Weapons Intelligence Sixth Directorate: Third (Armed Forces) Twelfth Directorate: Radio, Radio-Technical Directorate Unknown Intelligence Seventh (Surveillance) First Direction: Institute of Directorate Moscow Information Ninth (Guards) Second Direction: East Information Command Directorate and West Berlin Post Third: National Technical Operations Liberation Directorate Movements, Terrorism Administration Fourth: Operations Directorate from Cuba Personnel Directorate Special Investigations Collation of Operational Experience State Communications Physical Security Registry and Archives Finance Source: (Richelson 22, 27) Figure 2- Organization of the United States Intelligence Community President National Security Advisor National Security DNI State DOD DOJ DHS DOE Treasury Commerce Council Nuclear CIO INR USDI FBI Intelligence Foreign $$ Flow Attachés Weapons Plans DIA NSA NGA NRO Military Services NSB Coast Guard Collection MSIC NGIC (Army) MRSIC (Air Analysis AFMic Force) NCTC J-2's ONI (Navy) CIA Main DIA INSCOM (Army) NCDC MIA (Marine) MIT Source: (Martin-McCormick) . -

Hacks, Leaks and Disruptions | Russian Cyber Strategies

CHAILLOT PAPER Nº 148 — October 2018 Hacks, leaks and disruptions Russian cyber strategies EDITED BY Nicu Popescu and Stanislav Secrieru WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Siim Alatalu, Irina Borogan, Elena Chernenko, Sven Herpig, Oscar Jonsson, Xymena Kurowska, Jarno Limnell, Patryk Pawlak, Piret Pernik, Thomas Reinhold, Anatoly Reshetnikov, Andrei Soldatov and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer Chaillot Papers HACKS, LEAKS AND DISRUPTIONS RUSSIAN CYBER STRATEGIES Edited by Nicu Popescu and Stanislav Secrieru CHAILLOT PAPERS October 2018 148 Disclaimer The views expressed in this Chaillot Paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or of the European Union. European Union Institute for Security Studies Paris Director: Gustav Lindstrom © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2018. Reproduction is authorised, provided prior permission is sought from the Institute and the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Contents Executive summary 5 Introduction: Russia’s cyber prowess – where, how and what for? 9 Nicu Popescu and Stanislav Secrieru Russia’s cyber posture Russia’s approach to cyber: the best defence is a good offence 15 1 Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan Russia’s trolling complex at home and abroad 25 2 Xymena Kurowska and Anatoly Reshetnikov Spotting the bear: credible attribution and Russian 3 operations in cyberspace 33 Sven Herpig and Thomas Reinhold Russia’s cyber diplomacy 43 4 Elena Chernenko Case studies of Russian cyberattacks The early days of cyberattacks: 5 the cases of Estonia, -

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 998 17 November 2020

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 998 17 November 2020 Douglas Selvage. “Operation ‘Denver’: The East German Ministry of State Security and the KGB’s AIDS Disinformation Campaign, 1985-1986.” Journal of Cold War Studies 21:4 (Fall 2019): 71-123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00907. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR998 Review Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Review by Meredith L. Roman, SUNY Brockport ouglas Selvage’s in-depth exploration of the role that the Soviet Committee on State Security (KGB) and the East German Ministry for State Security (Stasi) and its Main Directorate for Intelligence (HVA) played in spreading Ddisinformation about the origins of the HIV virus that causes AIDS is particularly timely. The global COVID-19 pandemic has inspired conspiracy theories and disinformation efforts that are not based on scientific evidence but on racial prejudices in the case of the Trump White House, and, with regard to President Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin, a history inherited from its Soviet predecessor of identifying the CIA as an evil mastermind of infectious diseases. Selvage’s impressive research yields a detailed, multi-layered analysis of the ways in which different actors with varying objectives invested in the narrative that the U.S. government created the HIV virus as part of its bioweapons research program for its potential use in a future war or against despised groups domestically and internationally. “Operation ‘Denver’” is the first installment in a two-part essay project that draws partly on a monograph Selvage co-published in the German language in 2014 with historian Christopher Nehring.1 In this article, Selvage contends that the Stasi and HVA played an auxiliary role in the 1985-1986 efforts of the KGB to spread disinformation about AIDS, but assumed a more prominent role in the campaign by 1987 – the evidence of which he will outline in a future essay. -

The Public Eye, Spring 2008

The New Secular Fundamentalist Conspiracy!, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH PublicEye ASSOCIATES SPRING 2008 • Volume XXIII, No.1 $5.25 The North American Union Right-wing Populist Conspiracism Rebounds By Chip Berlet he same right-wing populist fears of Ta collectivist one-world government and new world order that fueled Cold War anticommunism, mobilized opposition to the Civil Rights Movement, and spawned the armed citizens militia movement in the 1990s, have resurfaced as an elaborate conspiracy theory about the alleged impending creation of a North American Union that would merge the United States, Canada, and Mexico.1 No such merger is seriously being con- templated by any of the three govern- ments. Yet a conspiracy theory about the North American Union (NAU) simmered in right-wing “Patriot Movement” alter- native media for several years before bub- bling up to reach larger audiences in the Ron Wurzer/Getty Images Wurzer/Getty Ron Dr. James Dobson, founder of the Christian Right group Focus on the Family, with the slogan of the moment. North American Union continues on page 11 IN THIS ISSUE Pushed to the Altar Commentary . 2 The Right-Wing Roots of Marriage Promotion The New Secular Fundamentalist Conspiracy! . 3 By Jean V. Hardisty especially welfare recipients, to marry. The fter the 2000 presidential campaign, I rationale was that marriage would cure their Reports in Review . 28 Afelt a shock of recognition when I read poverty. Wade Horn, appointed by Bush to that the George W. Bush Administration be in charge of welfare programs at the Now online planned to use its “faith-based” funding to Department of Health and Human Services www.publiceye.org . -

Conspiracy Theories.Pdf

Res earc her Published by CQ Press, a Division of SAGE CQ www.cqresearcher.com Conspiracy Theories Do they threaten democracy? resident Barack Obama is a foreign-born radical plotting to establish a dictatorship. His predecessor, George W. Bush, allowed the Sept. 11 attacks to P occur in order to justify sending U.S. troops to Iraq. The federal government has plans to imprison political dissenters in detention camps in the United States. Welcome to the world of conspiracy theories. Since colonial times, conspiracies both far- fetched and plausible have been used to explain trends and events ranging from slavery to why U.S. forces were surprised at Pearl Harbor. In today’s world, the communications revolution allows A demonstrator questions President Barack Obama’s U.S. citizenship — a popular conspiracists’ issue — at conspiracy theories to be spread more widely and quickly than the recent “9-12 March on Washington” sponsored by the Tea Party Patriots and other conservatives ever before. But facts that undermine conspiracy theories move opposed to tax hikes. less rapidly through the Web, some experts worry. As a result, I there may be growing acceptance of the notion that hidden forces N THIS REPORT S control events, leading to eroding confidence in democracy, with THE ISSUES ......................887 I repercussions that could lead Americans to large-scale withdrawal BACKGROUND ..................893 D from civic life, or even to violence. CHRONOLOGY ..................895 E CURRENT SITUATION ..........900 CQ Researcher • Oct. 23, 2009 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ........................901 Volume 19, Number 37 • Pages 885-908 OUTLOOK ........................902 RECIPIENT OF SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILVER GAVEL AWARD BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................906 THE NEXT STEP ................907 CONSPIRACY THEORIES CQ Re search er Oct. -

The European Union Approach to Disinformation and Misinformation the Case of the 2019 European Parliament Elections

University of Strasbourg European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation A.Y. 2018/2019 The European Union approach to disinformation and misinformation The case of the 2019 European Parliament elections Author: Shari Hinds Supervisor: Dr Florence Benoit- Rohmer Abstract In the last years, the phenomenon of so called “fake news” on social media has become more and more discussed, in particular after the 2016 US elections. The thesis examines how the European Union is approaching “fake news” on social media, taking the 2019 European Parliament elections as a case study. This research favours the words “disinformation” and “misinformation”, over “fake news”. It, firstly, explores the different way of spreading disinformation and misinformation and how this can affect our human rights. This thesis will, secondly, focus on the different approaches, remedies and solutions to false information, outlining their limits, in order to recommend to the European Union, the best policies to tackle the phenomenon. The research will, thirdly, focuses on how the European Institutions are currently approaching this issue on social media and the steps that have been taken to protect European citizens from disinformation and misinformation; at this purpose the relevant European policy documents will be analysed. This analysis is necessary to understand the ground of the EU elections. The thesis will conclude with the case study of 2019 European Parliament elections. It will find if there have been cases of disinformation on social media and if the actions taken by the European Union have been enough to protect the second largest elections in the world. Key words: fake news, disinformation, misinformation, co-regulation, Russian disinformation campaigns, European Union, 2019 European Parliament elections.