Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Plants Society South Gippsland Newsletter April, 2017 We Are Proud to Acknowledge Aboriginal People As the Traditional Owners of These Lands and Waters

Australian Plants Society South Gippsland Newsletter April, 2017 We are proud to acknowledge Aboriginal people as the traditional owners of these lands and waters From the Great Southern Rail Trail. February 2017 Photo by Graeme Rowe Inside this Newsletter: Twenty-three people attended our Twilight Picnic and walk to the Black Spur Creek 2017 program and other events & news Wetlands. In Graeme’s photo from the most including : easterly rail trail trestle bridge can be seen the Results of the AGM Tarwin River West Branch in left foreground, Plans for September weekend away in the its meandering course through the goldfields area of Central Victoria. middle ground, a flood plain in the foreground Vale Graeme Desmond Tuff (Tuffy) and steep valley wall in A possible new initiative for rare plants the distance. See Graeme Rowe’s article on the geomorphology inside this newsletter . 2 AUSTRALIAN PLANTS SOCIETY SOUTH GIPPSLAND GROUP For club enquiries: President 5674 2864 or Secretary 5659 8187 Program for 2017 Wednesday April 12th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA “Revegetation – Heart Morass and Black Spur Creek Wetlands” Matt Bowler, Project Delivery Team Leader, West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority. Wednesday May 10th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA "Gardening for Wildlife using Australian natives" Amy Akers, Australian Plant Enthusiast, Horticulturalist. More information in this newsletter – email your seed orders for Amy to bring on the night. Wednesday June 14th : 7.30 pm Uniting Church, 16 Peart Street, LEONGATHA “Gardens, Gardeners and APS Vic” Chris Long, President, APS Victoria July and August activities to be confirmed. -

Annual Report Contents About Museums Australia Inc

Museums Australia (Victoria) Melbourne Museum Carlton Gardens, Carlton PO Box 385 Carlton South, Victoria 3053 (03) 8341 7344 Regional Freecall 1800 680 082 www.mavic.asn.au 08 annual report Contents About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) .................................................................................................. 2 Mission Enabling museums and their Training and Professional Development President’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 3 services, including phone and print-based people to develop their capacity to inspire advice, referrals, workshops and seminars. Treasurer’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 4 Membership and Networking Executive Director’s Report ...................................................................................................................... 5 and engage their communities. to proactively and reactively identify initiatives for the benefit of existing and Management ............................................................................................................................................. 7 potential members and links with the wider museum sector. The weekly Training & Professional Development and Member Events ................................................................... 9 Statement of Purpose MA (Vic) represents -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

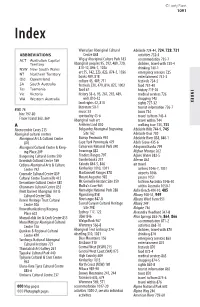

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Mount Gambier Cemetery Aus Sa Cd-Rom G

STATE TITLE AUTHOR COUNTRY COUNTY GMD LOCATION CALL NUMBER "A SORROWFUL SPOT" - MOUNT GAMBIER CEMETERY AUS SA CD-ROM GENO 2 COMPUTER R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA "A SORROWFUL SPOT" PIONEER PARK 1854 - 1913: A SOUTHEE, CHRIS AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.MTGA HISTORY OF MOUNT GAMBIER'S FIRST TOWN CEMETERY "AT THE MOUNT" A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF EARLY WYCHEPROOF & AUS VIC BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.WYCH.WYCH WYCHEPROOF DISTRICT HISTORICAL SOCIETY "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 4 R 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL 1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "BY THE HAND OF DEATH": INQUESTS HELD FOR KRANJC, ELAINE AND AUS VIC BOOK BAY 14 SHELF 2 614.1.AUS.VIC.GEE GEELONG & DISTRICT VOL.1 1837 - 1850 JENNINGS, PAM "HARMONY" INTO TASMANIAN 1829 & ORPHANAGE AUS TAS BOOK BAY 2 SHELF 2 R 362.732.AUS.TAS.HOB INFORMATION "LADY ABBERTON" 1849: DIARY OF GEORGE PARK PARK, GEORGE AUS ENG VIC BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 387.542.AUS.VIC "POPPA'S CRICKET TEAM OF COCKATOO VALLEY": A KURTZE, W. J. AUS VIC BOOK BAY 6 SHELF 2 R 929.29.KURT.KUR FACUTAL AND HUMOROUS TALE OF PIONEER LIFE ON THE LAND "RESUME" PASSENGER VESSEL "WANERA" AUS ALL BOOK BAY 3 SHELF 2 R 386.WAN "THE PATHS OF GLORY LEAD BUT TO THE GRAVE": TILBROOK, ERIC H. H. AUS SA BOOK BAY 7 SHELF 1 R 929.5.AUS.SA.CLA EARLY HISTORY OF THE CEMETERIES OF CLARE AND DISTRICT "WARROCK" CASTERTON 1843 NATIONAL TRUST OF AUS VIC BOOK BAY 16 SHELF 1 994.57.WARR VICTORIA "WHEN I WAS AT NED'S CORNER…": THE KIDMAN YEARS KING, CATHERINE ALL ALL BOOK BAY 10 SHELF 3 R 994.59.MILL.NED -

The Bill Provides That Any Available Evidence Must People Are Perfectly Valid

MAGISTRATES' COURT (AMENDMENT) BILL 1852 ASSEMBLY Wednesday, 18 May 1994 The bill provides that any available evidence must people are perfectly valid. However, many ordinary be disclosed early in the preparation of the case, people do not pay the fines simply because they with a view to reducing both the length and cost of cannot. They do not have the money and the cases. Some misgivings have been expressed by resources to pay them. Asset seizure on people with members of the police force who are concerned that low incomes would only increase their the proposal may create a situation in which disadvantageous position. additional costs are imposed on the police force in prosecuting trials. They are concerned that those As the honourable member for Melbourne said, it conducting a defence may seek to call for evidence would certainly hit people on lower incomes or witnesses at great cost to the police simply to disproportionately harder than people on higher establish what evidence is available, despite all incomes. The provision would not so much affect along having the intention to plea bargain or even people using the cover of corporate shelf companies plead guilty. On balance the opposition believes the to avoid paying fines as it would affect people on positive aspects of the provision outweigh the low incomes with legitimate hardship. difficulties that might arise. However, the concerns expressed by members of the police force must be The evidence provided by the Attorney-General taken on board and the practice must be monitored suggesting that many people are deliberately and closely. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 350 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. AUTHOR THANKS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Climate map data adapted from Peel MC, Anthony Ham Finlayson BL & McMahon TA (2007) ‘Updated Thanks to Maryanne Netto for sending me World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate to such wonderful places – your legacy will Classification’, Hydrology and Earth System endure. To co-authors Trent and Kate who Sciences, 11, 163344. brought such excellence to the book. To David Andrew for so many wise wildlife tips. And to Cover photograph: Loch Ard Gorge, Port every person whom I met along the road – Campbell National Park, David South/Alamy. -

Annual Report 2013-2014 Koorie Heritage Trust Inc 295 King Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 (03) 8622 2600

Annual Report 2013-2014 Koorie Heritage Trust Inc 295 King Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 (03) 8622 2600 www.koorieheritagetrust.com ABN 23 407 505 528 We acknowledge and pay our respects to the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung peoples of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we are located. Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are advised that this document may contain the names and/ or images of people who have passed away. Cover image: Sandra Aitken, Gunditjmara Healing Walk Eel Trap 2013 Plastic hay bale twine AH 3913 Photo: James Henry Design: Darren Sylvester Editor: Chris Keeler Text: Koorie Heritage Trust Staff Publication Co-ordination: Giacomina Pradolin 2 Contents 04 Wominjeka/Welcome: Vision and Purpose 06 Chairperson’s Report 08 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 10 Our Strategic Plan 2014-2016 11 Strategic Goals 2014-2016 12 Our Activities 14 Collections 16 Exhibitions & Public Programs 18 Koorie Family History Service 22 Cultural Education 24 Registered Training Organisation 25 Retail and Venue Hire 26 Partnerships, Advocacy and Research 28 Media and Publicity 30 Our Supporters 32 Our Donors 34 Our Governance 35 Our Staff 36 Treasurer’s Report 3 Wominjeka/Welcome: Vision and Purpose Our Vision To live in a society where Aboriginal culture and history are a fundamental part of Victorian life. Our Purpose To promote, support and celebrate the continuing journey of the Aboriginal people of south-eastern Australia. Our Motto Gnokan Danna Murra Kor-ki – Give me your hand my friend. Our Values Respect, Honesty, Reciprocity, Curiosity Our Centre Provides a unique environment rich in culture, heritage and history which welcomes and encourages Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people to come together in the spirit of learning and reconciliation. -

The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council

THE VICTORIAN 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INTRODUCTION Aboriginal peoples of Through these events, the Council’s integrity Victoria have fought and sound decision making were affirmed. for generations for The Parliamentary Inquiry produced a positive recognition of their report on the Council’s work. Amendments to unique relationship the Act passed in 2016 gave the Council more with and custodianship responsibilities. And the judicial decision upheld of their lands. This the Council’s decision, endorsed the Council’s month, we celebrate decision making processes, and ordered costs in the anniversaries of favour of the Council. two key milestones in The Council’s work has also been significantly the fight for Aboriginal rewarding. Aboriginal cultural heritage is now recognition and self determination. managed by Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs) Fifty years ago on 27 May, Australians voted in more than fifty per cent of the state. We have overwhelmingly to amend the Constitution to a dedicated unit working for the return and include Aboriginal peoples in the census and protection of our Ancestors’ remains. And we are to allow the Commonwealth to create laws for/ seeing greater recognition of Traditional Owners about Aboriginal peoples. and their roles with respect to cultural heritage management. Ten years ago on 28 May, the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 came into effect. These milestones could not have occurred without the commitment of so many people, The Act created the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage those before us and those who walk alongside Council, the first statutory body in Victoria whose us today. members must be Traditional Owners. -

To Download a Free Pdf Version of Finding Your Story

A Resource Manual to the records of The Stolen Generations in Victoria Published by: Public Record Office Victoria, Cover illustration includes the PO Box 2100, North Melbourne, Victoria, following images Australia, 3051 Koorie Heritage Trust Inc: © State of Victoria 2005 AH1707 This work is copyright. Apart from any use MacKillop Family Services: permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part 1879 St Josephs Babies Home may be reproduced by any process without prior Broadmeadows c1965 written permission from the publisher. Enquiries should be directed to the publisher. Private Collection Jim Berg JP: Images from Framlingham Research and content by: James Jenkinson Edited and indexed by: Kerry Biram Public Record Office Victoria: Designed and produced by: Deadly Design VPRS 6760/P0, Unit 1, Item 6, Aboriginal Graphic Design & Printing Estrays, Chief Protector of Aborigines Printed in Australia VPRS 1226/P0, Unit 4, Item X1857, National Library of Australia Supplementary Registered Inward Cataloguing-in-Publication Correspondence, Finding your story: a resource manual to the Chief Secretary records of the stolen generations in Victoria. VPRS 14562/P4, unit 6, 555 Lake Tyers Special School, Department of Education Includes index. ISBN 0 9751068 2 1. State Library of Victoria: H20918/2929, Aboriginal Woman Holding Child, 1. Aboriginal Australians - Victoria - Archives. Three Quarter Length, Full Face, c1890’s, 2.Children, Aboriginal Australian - Government Henry King photographer policy -Victoria - Archives. 3. Victoria - Archival resources. -

Where Are They Now Redesdale Mia Mia Primary School Students Jasper Cadusch

ISSUE NO. 108 September 2019 facebook.com/RedesdaleMiaMia facebook.com/RedesdaleMiaMia Where Are They Now Redesdale Mia Mia Primary School Students Jasper Cadusch Jasper aligning laser beams in his optics lab at The University of Melbourne. Story page 6. Veterinary Surgeon Mobile: Metcalfe: Malmsbury: Mia Mia Small animal veterinary work by appointment Dr Julie Kendall m: 0447 573 247 e: [email protected] 2 BRIDGE CONNECTION Edition 108 September 2019 Community Newspaper for the Redesdale and Mia Mia Region Editorial Hello Dear Readers, Bridge Connection Mission Statement Welcome to Spring, The Redesdale Fire Brigade would like to reward your efforts by once again announcing the " Best prepared The mission of Bridge Connection is to bring property award ". A $100 Bunnings voucher is on offer. people together by: more info on Page 4. The Bridge Connection Committee would like to send 1. Providing information about local issues, goals a fond farewell to Jamie Coombs we will miss your and events, and to celebrate local achievements, smiling face at the cafe but wish you well as you head home. Photos on page 14. 2. Encouraging economic growth in the area, On front page & continuing on page 6. A new segment 3. Fostering geographic identity, and toIf you find would out where like to our submit Primary a story School about student you or are your now children for the where are they now segment send to 4. Providing a platform for public debate, the below e-mail address Email [email protected] Bridge Connection is published -

Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development

Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development This annual report covers the Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development as an individual entity. Published by the Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, Melbourne Victoria. October 2008 Annual Report 2007–08 This report is also available on the internet at: www.diird.vic.gov.au © Copyright State of Victoria 2008 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development 121 Exhibition Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Postal Address PO Box 4509 Melbourne VIC 3001 Telephone: (03) 9651 9999 Facsimile: (03) 9651 9962 www.diird.vic.gov.au Designed and produced by: Publicity Works Printed by: Impact Digital The paper used in this report is accredited to both ISO 14001 and Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) standards ensuring environmentally sustainable and responsible processes through all stages of material sourcing and manufacture. EMAS standards include third party auditing, public reporting and continual improvement programmes. Contents e Secretary’s foreword nt2 coOur Ministers 4 Economic context 5 Role and structure of the Department 6 Organisational chart 10 Governance arrangements 12 Strategic objectives 13 Develop 14 Connect 32 Promote 44 Shape 52 Strengthen 60 Financials 65 Appendices 116 1 Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development Annual Report 07–08 Secretary’s foreword or This has been a signifi cant year for the Department of Ensuring that 90 per cent of young people in Victoria w Innovation, Industry and Regional Development. -

Victorian Program 18 April–19 May 2020 There Are No Shortcuts

proudly presents Victorian Program 18 April–19 May 2020 There are no shortcuts. Protecting and growing wea lth takes discipline and time. Trust is earned. Contents Aboriginal Cultural Heritage 10 Oral and Social History 76 Advocacy, Activism, and Conservation 14 Queer History 84 Welcome to the 2020 Cultural Expressions 18 Women’s History 88 Australian Heritage Festival Gaols, Hospitals, and Asylums 24 Acknowledgements 92 We extend an invitation to all Victorians and visitors The 2020 Australian Heritage Festival theme is Our Gardens, Landscapes, alike to join us in celebrating the best of our shared heritage for the future. It presents a multi-faceted and the Environment 26 Index 95 heritage during this year’s Australian Heritage Festival. opportunity to foster an understanding of our shared cultural heritage, and an understanding that our diverse The National Trust of Australia (Victoria) is the most heritage must be used, lived and celebrated in the Industrial, Farming, and significant grassroots, cultural heritage organisation in present to ensure its preservation into the future. the state of Victoria. Each year we coordinate a diverse Maritime Heritage 36 program of events for the Australian Heritage Festival. Our presentation of the Australian Heritage Festival aligns with the National Trust’s mission to inspire the Living Museums, Galleries, What our icons mean Events are held across the state, organised by a wide community to appreciate, conserve and celebrate its variety of community groups, local councils, individuals, diverse natural, cultural, social, and Indigenous heritage. Archives, and Collections 42 heritage agencies, and other kindred organisations. The While our organisation works hard to advocate and fight Accessible Festival begins annually on 18 April, the International for our shared heritage on a daily basis, the Festival is an Toilets Day for Monuments and Sites, and in 2020 will draw to opportunity to reflect on the places where we live, work, Local and Residential a close on 19 May.