Press Steve Mcqueen Interview, October 1, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve Mcqueen”, the New Journal and Guide, February 03, 2014

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve McQueen”, The new journal and guide, February 03, 2014 Artist and filmmaker Steven Rodney McQueen was born in London on October 9, 1969. His critically-acclaimed directorial debut, Hunger, won the Camera d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. He followed that up with the incendiary offering Shame, a well- received, thought-provoking drama about addiction and secrecy in the modern world. In 1996, McQueen was the recipient of an ICA Futures Award. A couple of years later, he won a DAAD artist’s scholarship to Berlin. Besides exhibiting at the ICA and at the Kunsthalle in Zürich, he also won the coveted Turner Prize. He has exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Documenta, and at the 53rd Venice Biennale as a representative of Great Britain. His artwork can be found in museum collections around the world like the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. In 2003, he was appointed Official War Artist for the Iraq War by the Imperial War Museum and he subsequently produced the poignant and controversial project Queen and Country commemorating the deaths of British soldiers who perished in the conflict by presenting their portraits as a sheet of stamps. Steve and his wife, cultural critic Bianca Stigter, live and work in Amsterdam which is where they are raising their son, Dexter, and daughter, Alex. Here, he talks about his latest film, 12 Years a Slave, which has been nominated for 9 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. -

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

Hollywood and Film Critics

Hollywood and film critics: Is journalistic criticism about cinema now a part of the culture industry helping economy more than art? Argo: a case study of the movie and film reviews published in the printed media in United States student: Seyedjavad Rasooli Tutor: Jaume Soriano Coordinator: María Dolores Montero Sánchez DEPARTAMENTO DE MEDIOS, COMUNICACIÓN Y CULTURA Barcelona, September de 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................4 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................. 6 Frankfurt School and Critical theory ......................................................................................... 6 The concept of culture industry................................................................................................ 8 The Culture Industry and Film................................................................................................. 11 About Hollywood .................................................................................................................... 12 Hollywood and Ideology.......................................................................................................... 15 About Film Critic Genre.......................................................................................................... -

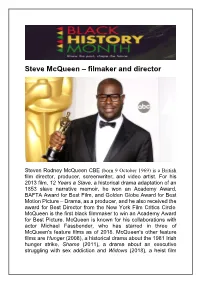

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

BFI Poll Reveals UK's Favourite Black Star Performance

BFI POLL REVEALS UK’S FAVOURITE BLACK STAR PERFORMANCE: SIDNEY POITIER AS “MISTER TIBBS” In the Heat of the Night Angela Bassett’s courageous portrayal of Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It voted as top performance by over 100 industry experts London: (embargoed until 16:30 BST) Thursday 20 October, 2016 – To mark this week’s official launch of its BLACK STAR season, the BFI announced today that Sidney Poitier’s critically-acclaimed and seminal performance as Detective Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison, 1967) has been voted the public’s Favourite Black Star Performance in a poll which included 100 performances spanning over 80 years in film and TV. Running alongside the public poll, a separate poll of over 100 industry experts voted for Angela Bassett’s Oscar®- nominated performance as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It (dir. Brian Gibson, 1993). UK Public Poll Pam Grier followed in second place with her terrific turn as the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown – an homage to the 1970’s era of Blaxploitation films in America; Michael K. Williams was number three with his unforgettable portrayal of the legendary Omar Little, the openly gay, notorious stick-up man with a strict moral code feared by drug dealers across the city of Baltimore, in the socially and politically charged hit television series The Wire. British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor followed in fourth with his visceral portrayal of Solomon Northup, his break-out performance in Steve McQueen’s ground-breaking, Oscar®-winning true story, 12 Years A Slave; and Morgan Freeman rounded out the top five with his acclaimed, quiet and layered performance in Frank Darabont’s Oscar®-nominated cult classic, The Shawshank Redemption. -

Widescreen Weekend 2008 Brochure (PDF)

A5 Booklet_08:Layout 1 28/1/08 15:56 Page 41 THIS IS CINERAMA Friday 7 March Dirs. Merian C. Cooper, Michael Todd, Fred Rickey USA 1952 120 mins (U) The first 3-strip film made. This is the original Cinerama feature The Widescreen Weekend continues to welcome all which launched the widescreen those fans of large format and widescreen films – era, and is about as fun a piece of CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and IMAX – Americana as you are ever likely and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of to see. More than a technological curio, it's a document of its era. the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. HAMLET (70mm) Sunday 9 March Widescreen Passes £70 / £45 Dir. Kenneth Branagh GB/USA 1996 242 mins (PG) Available from the box office 0870 70 10 200 Kenneth Branagh, Julie Christie, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, Judi Patrons should note that tickets for 2001: A Space Odyssey are priced Dench, Charlton Heston at £10 or £7.50 concessions Anyone who has seen this Hamlet in 70mm knows there is no better-looking version in colour. The greatest of Kenneth Branagh’s many achievements so 61 far, he boldly presents the full text of Hamlet with an amazing cast of actors. STAR! (70mm) Saturday 8 March Dir. Robert Wise USA 1968 174 mins (U) Julie Andrews, Daniel Massey, Richard Crenna, Jenny Agutter Robert Wise followed his box office hits West Side Story and The Sound of Music with Star! Julie 62 63 Andrews returned to the screen as Gertrude Lawrence and the film charts her rise from the music hall to Broadway stardom. -

THE HORIZON a Newsletter for Alumni, Families and Friends of Shelton School December 2015

THE HORIZON A Newsletter for Alumni, Families and Friends of Shelton School December 2015 Celebrating 40 years! 2014-2015 Annual Report of Gifts (See Page 27) THE HORIZON TABLE OF CONTENTS December 2015 Dedicated to June Ford Shelton 1 From the Executive Director 2 Shelton Celebrates Founders and Fortieth 4 Development Doings 6 Outreach/Training Offerings 7 Shelton Outreach is Everywhere 8 Shelton Speech / Language / Hearing Clinic 9 Shelton Evaluation Center It’s been 40 years since June Shelton and a 10 Accolades handful of parents put into action their vision for 11 Lower School News a school that would help students who needed a different environment in which to learn. They 12 Upper Elementary School News did it in faith that it was the right thing to do. We truly believe that Shelton is a place that 13 Middle School News transforms lives every day. We do it humbly, 14 Upper School News with the dedication of all involved — students, parents, faculty, staff, administrators, and all 16 Fine Arts Features others in the Speech Clinic, Evaluation Center, 18 From the Head of School and Outreach / Training Program. This Horizon is dedicated to June Ford Shelton and her pioneer 19 Spotlight on Sports work in the field of learning differences. With every good faith, we look forward to the next 20 Alumni Updates forty years of a mission that still is timely. We 21 Library News / Technology Update think she would be so pleased to see Shelton today, and she’d be the first one to encourage us 22 Parents’ Page to charge forward. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

12 Anni Schiavo – Scheda Verifiche

12 ANNI SCHIAVO – SCHEDA VERIFICHE 12 YEARS A SLAVE (Scheda a cura di Simonetta Della Croce) CREDITI Regia: Steve McQueen. Soggetto: dall’autobiografia 12 anni schiavo di Solomon Northup. Sceneggiatura: John Ridley. Fotografia: Sean Bobbitt. Musiche: Hans Zimmer. Montaggio: Joe Walker. Scenografia: Adam Stockhausen. Arredamento: Alice Baker. Costumi: Patricia Norris. Interpreti: Chiwetel Ejiofor (Solomon Northup/Platt), Michael Fassbender (Edwin Epps), Benedict Cumberbatch (William Ford), Paul Dano (Tibeats), Garret Dillahunt (Armsby), Paul Giamatti (Freeman), Scoot McNairy (Brown), Lupita Nyong'O (Patsey), Adepero Oduye (Eliza), Sarah Paulson (Sig.ra Epps), Brad Pitt (Bass), Alfre Woodard (Harriet Shaw), Chris Chalk (Clemens Ray), Taran Killam (Hamilton), Bill Camp (Radburn), Dwight Henry (Zio Abram), Bryan Batt (Giudice Turner), Quvenzhané Wallis (Margaret Northup), Cameron Zeigler (Alonzo Northup), Tony Bentley (Sig. Moon), Christopher Berry (James Burch), Mister Mackey Jr. (Randall). Origine: USA. Anno di edizione: 2014. Durata: 133’. Sinossi Nel 1841, Solomon Northup – un nero nato libero nel nord dello stato di New York – viene rapito e portato in una piantagione di cotone in Louisiana, dove è obbligato a lavorare in schiavitù per dodici anni, sperimentando sulla propria pelle la feroce crudeltà del perfido padrone Edwin Epps. Allo stesso tempo, però, gesti di inaspettata gentilezza gli permetteranno di trovare la forza di sopravvivere e di non perdere la propria dignità fino all'incontro con Bass, un abolizionista canadese, che lo aiuterà a tornare un uomo libero. 1 Unità 1 - (Minutaggio da 00:00 a 06:08) 1. Come inizia il film? 2. Com'è la struttura narrativa del film? 3. La sessualità è spesso evidenziata in “12 anni schiavo”.