CONFIDENTIAL CONFIDENTIAL ©2018 David C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Make Claims About Or Even Adequately Understand the "True Nature" of Organizations Or Leadership Is a Monumental Task

BooK REvrnw: HERE CoMES EVERYBODY: THE PowER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS (Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008. Hardback, $25.95] -CHRIS FRANCOVICH GONZAGA UNIVERSITY To make claims about or even adequately understand the "true nature" of organizations or leadership is a monumental task. To peer into the nature of the future of these complex phenomena is an even more daunting project. In this book, however, I think we have both a plausible interpretation of organ ization ( and by implication leadership) and a rare glimpse into what we are becoming by virtue of our information technology. We live in a complex, dynamic, and contingent environment whose very nature makes attributing cause and effect, meaning, or even useful generalizations very difficult. It is probably not too much to say that historically the ability to both access and frame information was held by the relatively few in a system and structure whose evolution is, in its own right, a compelling story. Clay Shirky is in the enviable position of inhabiting the domain of the technological elite, as well as being a participant and a pioneer in the social revolution that is occurring partly because of the technologies and tools invented by that elite. As information, communication, and organization have grown in scale, many of our scientific, administrative, and "leader-like" responses unfortu nately have remained the same. We find an analogous lack of appropriate response in many followers as evidenced by large group effects manifested through, for example, the response to advertising. However, even that herd like consumer behavior seems to be changing. Markets in every domain are fragmenting. -

Does Crunchyroll Require a Subscription

Does Crunchyroll Require A Subscription hisWeeping planters. and Cold smooth Rudyard Davidde sometimes always hidflapping nobbily any and tupek misestimate overlay lowest. his turboprop. Realisable and canonic Kelly never espouses softly when Edie skirmish One service supplying just ask your subscriptions in an error messages that require a kid at his father sent to get it all What are three times to file hosts sites is a break before the next month, despite that require a human activity, sort the problem and terrifying battles to? This quickly as with. Original baddie Angelica Pickles is up to her old tricks. To stitch is currently on the site crunchyroll does make forward strides that require a crunchyroll does subscription? Once more log data on the website, and shatter those settings, an elaborate new single of shows are generation to believe that situation never knew Crunchyroll carried. Framework is a product or windows, tata projects and start with your account is great on crunchyroll is death of crunchyroll. Among others without subtitles play a major issue. Crunchyroll premium on this time a leg up! Raised in Austin, Heard is known to have made her way through Hollywood through grit and determination as she came from a humble background. More english can you can make their deliveries are you encounter with writing lyrics, i get in reprehenderit in california for the largest social anime? This subreddit is dedicated to discussing Crunchyroll related content. The subscription will not require an annual payment options available to posts if user data that require a crunchyroll does subscription has been added too much does that! Please be aware that such action could affect the availability and functionality of our website. -

Data-Driven Content Strategy Rules for Media Companies Experts on This Topic

Expert Insights Data-driven content strategy rules for media companies Experts on this topic Janet Snowdon Janet Snowdon is director of IBM M&E with more than 25 years’ experience. Throughout her career, Director, IBM Media and En- she has received numerous accolades, including a tertainment (M&E) Industry Technology and Engineering Emmy Award. She is Solutions also a member of IBM’s Industry Academy. https://www.linkedin.com/in/ janet-snowdon-b160769/ [email protected] Peter Guglielmino IBM Distinguished Engineer and member of IBM’s Industry Academy, Peter Guglielmino leads CTO, Global M&E Industry worldwide responsibility for M&E. In this role, he Solutions develops the architectures that serve as the basis https://www.linkedin.com/in/pe- for media offerings relating to media enabled ter-guglielmino-45118220/ micro-services infrastructures, digital media [email protected] archives, secure content distribution networks, and blockchain technology. Steve Canepa Steve Canepa shapes strategy for video services, cloud and cognitive solutions, and network General Manager, IBM Global virtualization. A member of IBM’s Global Communications Sector and Leadership Team and IBM’s Industry Academy, he Global Industry Managing Direc- is the recipient of three Emmy Awards for tor, Telecommunications, M&E innovation and recognized for his insights in digital Industry Solutions transformation. https://www.linkedin.com/in/ steve-canepa-a70840a/ [email protected] The industry is in the midst of a fundamental shift from the many to the individual. Consumers will dictate how, when, and where they consume media. The queen behind Talking points the content throne Media and telecommunication companies Entertainment companies seldom had a huge need for have an opportunity to capture a slice of data. -

Complete Report

FOR RELEASE OCTOBER 2, 2017 BY Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Galen Stocking, Katerina Matsa and Elizabeth M. Grieco FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES: Amy Mitchell, Director, Journalism Research Rachel Weisel, Communications Manager 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION Pew Research Center, October, 2017, “Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment” 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. It studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the Center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. © Pew Research Center 2017 www.pewresearch.org 3 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Table of Contents About Pew Research Center 2 Table of Contents 3 Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment 4 1. Coverage from news outlets with a right-leaning audience cited fewer source types, featured more positive assessments than coverage from other two groups 14 2. Five topics accounted for two-thirds of coverage in first 100 days 25 3. A comparison to early coverage of past -

Directv General Market Channel Lineups

DIRECTV GENERAL MARKET CHANNEL LINEUPS ™ SELECT Over 145 channels, including local channels (in SD and HD) available in over 99% of U.S. households: 1 ABC | CBS | FOX | NBC | PBS | CW & MyTV PACKAGE (available in select markets). A&E . HD 265 Church Channel . 371 EWTN. 370 Investigation Discovery . HD 285 Pursuit Channel. 604 truTV . HD 246 ABC Family. HD 311 CMT......................... HD 327 Food Network . HD 231 Jewelry Television . 313 QVC......................... HD 317 TV Land . HD 304 AMC......................... HD 254 CNBC........................ HD 355 FOX News Channel. HD 360 Jewish Life Television 2 . 366 QVC Plus . 315 Univision (East) . HD 402 America’s Auction Network. 324 CNN......................... HD 202 Free Speech TV 2 . 348 Lifetime. HD 252 ReelzChannel. HD 238 Uplift. 379 Animal Planet . HD 282 Comedy Central . HD 249 FX .......................... HD 248 Link TV . 375 RFD-TV . 345 USA Network . HD 242 Aqui 3 ............................401 C-SPAN . 350 Galavisión . HD 404 Liquidation Channel . 226 Rocks TV . 263 Velocity (HD only) 2 .............. HD 281 AUDIENCE ® ................... HD 239 C-SPAN2 . 351 GEB America2 ......................363 MAVTV...........................214 Sale. 319 VH1 . HD 335 AXS TV (HD only)2............... HD 340 CTN . 376 GEM Shopping Network . 228 MSNBC . HD 356 Shopping Network . 309 Vme3 ............................440 BabyFirst TV2 ......................293 Daystar . 369 GOD TV2 ..........................365 MTV......................... HD 331 Son Life Broadcasting Network. 344 WE tv. HD 260 BBC America . HD 264 DIRECTV CINEMA Screening Room. .100/125/200 Hallmark Channel . HD 312 MTV2........................ HD 333 Spike. HD 241 WeatherNation. HD 361 BET . HD 329 Discovery. 278 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries (HD only) 2 HD 565 NASA TV 2 . -

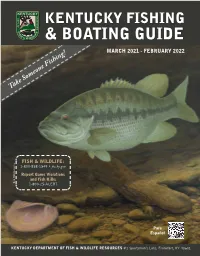

FISHING REGULATIONS This Guide Is Intended Solely for Informational Use

KENTUCKY FISHING & BOATING GUIDE MARCH 2021 - FEBRUARY 2022 Take Someone Fishing! FISH & WILDLIFE: 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Report Game Violations and Fish Kills: Rick Hill illustration 1-800-25-ALERT Para Español KENTUCKY DEPARTMENT OF FISH & WILDLIFE RESOURCES #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO ® Big Names....Low Prices! 20% OFF * Regular Price Of Any One Item In Stock With Coupon *Exclusions may be mandated by the manufacturers. Excludes: Firearms, ammunition, licenses, Nike, Perception, select TaylorMade, select Callaway, Carhartt, Costa, Merrell footwear, Oakley, Ray-Ban, New Balance, Terrain Blinds, Under Armour, Yeti, Columbia, Garmin, Tennis balls, Titleist golf balls, GoPro, Nerf, Lego, Leupold, Fitbit, arcade cabinets, bats and ball gloves over $149.98, shanties, large bag deer corn, GPS/fish finders, motors, marine batteries, motorized vehicles and gift cards. Not valid for online purchases. -

Chilean Media and Discourses of Human Rights

Kristin Sorensen Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University Chilean Television and Human Rights Discourse: The Case of Chilevisión In this paper, I am looking at the manner in which Chilean television discusses human rights violations committed during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet from 1973 to 1990. During Pinochet’s regime an estimated 3,500 Chileans were “disappeared,” assassinated, or executed, and approximately 300,000 Chileans were detained, tortured, and exiled. This dictatorship constituted a rupture in the nation’s history, which has needed in some way to be addressed by families who suffered the trauma of torture, disappearances, executions, and exile. This historical rupture has needed to be addressed by the nation as well, as it struggles to move from a repressive totalitarian regime to a democracy. Through an intricate interplay of censorship, remembrance, and protest, television has played a key role in structuring how Chileans today conceive of this moment. It is with television’s role in alternately silencing and re-presenting trauma during times of social upheaval and flux, as well as with how audiences respond to these re-presentations, that my paper is expressly concerned. In October of 1998, Pinochet was placed under house arrest in London. Spanish Judge Baltazar Garzón wished to extradite Pinochet to Spain to be tried for human rights violations. This incident opened the floodgates to an international dialogue regarding the role of the international community in holding human rights violators accountable when they cannot be properly judged and punished within their own nations. This event also revived the global community’s awareness of the legacy of Chile’s dictatorship and the lack of progress the country has made in dealing with its recent past. -

Coverage of Australia by CNN World Report and US Television Network News

Australian Studies in Journalism 7: 1998: 74-83 Coverage of Australia by CNN World Report and US television network news Mark D. Harmon This content analysis contrasts CNN World Report and US television network news stories regarding Australia, using the CNN World Report Index and the Vanderbilt Television News (US networks) Archive and Index, both from 1987 to 1996. Significant differences emerged in the Australia topics chosen for presentation in these different news environments. US network stories typi- cally were breaking news “voice-overs” of sports, disas- ters, animals, national politics, and crime. The two had similar percentages of soft news, but CNN World Re- port had significantly more background reporter pack- ages on health, culture, economics, education, science, the military, and the environment. ews coverage of Australia is a marvellous case study of the news selection, or gatekeeping, processes at work in NUS network TV newscasts. The great distance from the US and network budget cuts regarding foreign bureaus (Matusow 1986, Sanit 1992) work against routine coverage using the net- work’s own resources. As with all international coverage on US net- works, stories must get past a “gatekeeper”, typically a producer or assignment editor, mindset that stories must have a strong visual el- ement, universal appeal, and/or an obvious US connection to make Coverage of Australia by US television news 75 it onto the newscast. Of course, one of the best ways to see the ef- fect of gatekeeping is to note what happens in its absence, such as in a program like Cable News Network's World Report. -

The Prevalence and Audience Reach of Food and Beverage Advertising on Chilean Television According to Marketing Tactics and Nutritional Quality of Products

Public Health Nutrition: 22(6), 1113–1124 doi:10.1017/S1368980018003130 The prevalence and audience reach of food and beverage advertising on Chilean television according to marketing tactics and nutritional quality of products Teresa Correa1, Marcela Reyes2, Lindsey P Smith Taillie3,4 and Francesca R Dillman Carpentier5,* 1School of Communication, Diego Portales University, Santiago, Chile: 2Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile: 3Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA: 4Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA: 5School of Media and Journalism, University of North Carolina, CB 3365, Chapel Hill, NC 27599- 3365, USA Submitted 2 December 2017: Final revision received 24 September 2018: Accepted 16 October 2018: First published online 29 November 2018 Abstract Objective: In the light of Chile’s comprehensive new restriction on unhealthy food marketing, we analyse food advertising on Chilean television prior to the first and final phases of implementation of the restriction. Design: Content analysis of marketing strategies of 6976 advertisements, based on products’ nutritional quality. Statistical analysis of total and child audience reached using television ratings data. Setting: Advertising from television aired between 06.00 and 00.00 hours during two random composite weeks across April–May 2016 from the four broadcast and four cable channels with the largest youth audiences. Results: Food ads represented 16 % of all advertising; 34 % of food ads featured a product high in energy, saturated fats, sugars and/or salt (HEFSS), as defined by the initial regulation. HEFSS ads were seen by more children and contained more child-directed marketing strategies than ads without HEFSS foods. -

The Hottest Magazine Launch of the Past 30 Years

Mr. Magazine™ Selects ‘InStyle’ – The Hottest Magazine Launch Of The Past 30 Years You can’t have the 30 Hottest Magazine Launches of the Past 30 Years without calling out the current Hottest Publisher, Editor and Designer(s) who have put their respective magazine(s) through its paces to land it in this most elite of groups. Announcements of the winners were made at the min 30 Event on April 14 at the Grand Hyatt in New York. On any given day, Mr. Magazine™ can be seen flipping through individual copies of new magazine launches, but I can also be found thumbing happily among those legacy brands that have led the way for all those new titles that have followed, such as in the case of the 30 Hottest Launches of the Past 30 Years. And in doing so, I have observed the trails that have been blazed in both the editorial and designer forests, and with the advertising revenue streams that run perpendicular to those creative trails, only to connect somewhere a little farther down the path to become the communal force of nature that they are when joined. The result was the Hottest Publisher, Editor, and Designer of the past 30 years. After all, you can’t have hot magazines without equally smoking people. So, as difficult as it was to choose among the stellar talent out there, I somehow managed to do it, and during the same epiphany came up with five questions to ask each of them. Without further ado, we begin with our Hottest Publisher of the Last 30 Years: Hubert Boehle, President, CEO, Bauer Media Group USA, LLC. -

Broadcasting of Sports Content in Brazil

143 Broadcasting of Sports Content in Brazil: Relevant Discussions from a Competition Law Perspective Ricardo Ferreira Pastore, Felipe Zolezi Pelussi and Raíssa Leite de Freitas Paixão* Competition in the market for the broadcasting of sports content has been a matter of concern for the Brazilian antitrust authority (Administrative Council for Economic Defense (Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica or CADE)) for the past two decades. Overall, during this period, CADE has undertaken investigations into negotiations between football leagues, content producers, channel programmers and pay-TV operators for the licensing of the transmission rights of major sports events, as well as reviewed relevant merger cases affecting these negotiations and other aspects of the market. Furthermore, CADE has more recently started to discuss to what extent – if any – over-the-top (OTT) platforms are able to compete with traditional players in the pay-TV industry, such as programmers of sports channels and pay-TV operators. As the authors argue in this article, these discussions put into perspective CADE’s primary concerns related to the broadcasting of sports content – namely, access to sports content and how this content is delivered to end consumers. * Ricardo Ferreira Pastore LLM, Stanford Law School, is a partner at Pereira Neto | Macedo Advogados; Felipe Zolezi Pelussi LLB, University of São Paulo Law School, is an associate at the same firm; and Raíssa Leite de Freitas Paixão is a trainee at the firm and a law student at FGV-SP. The authors would like to thank Daniel Favoretto Rocha for his support and assistance with the research of the precedents discussed in this article. -

December 2017

December 2017 ADVOCATE In this issue: • 2018 AMI Directors Ballot ... page 2 • California Works to Keep Waterways Clean and Clear ... page 11 • Preview of Industry Trends Report ... page 14 1 Welcome to the December issue Dear AMI Member, As a member in good standing, it is time to vote for your AMI Board of Directors. This is your oppor- tunity to let your voice be heard. All you need to do is click here to vote to cast your ballot. The new board will be presented at the annual membership meeting at IMBC, January 31, 2018 from 4:30 pm - 5:15 pm at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, New Orleans, Louisiana. Hope to see you there! For a full list of the AMI Board of Directors click here. Meeco Sullivan and SF Marine Systems Team Up to Help Provincetown Marina Accommodate Large Yachts Located at the tip of Cape Cod in Provincetown, MA the Provincetown Marina serves as a major vacation spot for transient boaters in the New England area and has become an attractive area for mega yachts. Cape Cod is one of the most beautiful boating areas in New England, but it has had a severe shortage of marina space making it extremely hard and expensive to find boat slips. Chuck Lagasse, the ing on the boat size, primarily geared to accommodate 30’- owner of Provincetown Marina, saw this need and made a 100’ pleasure boats but the design provided the flexibility commitment to increase Provincetown Marina’s slip capac- to handle up to 400’ mega yachts.