Natural Resource Management Strategies on Leyte Island, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (As of 24 Mar)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (as of 24 Mar) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_REHAB_24032014_v1 BIRI PALAPAG LAVEZARES SAN JOSE ALLEN ROSARIO BOBON MONDRAGON LAOANG VICTORIA SAN CATARMAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL SAN CATUBIG ANTONIO PAMBUJAN GAMAY N O R T H E R N S A M A R LAPINIG SAN SAN ISIDRO VICENTE LOPE DE VEGA LAS NAVAS SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE SAN POLICARPIO CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO MASLOG ORAS SANTA GANDARA TAGAPUL-AN MARGARITA DOLORES SAN JOSE DE BUAN SAN JORGE CAN-AVID PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO TARANGNAN SANTO PARANAS NI-O (WRIGHT) TAFT CITY OF JIABONG CATBALOGAN SULAT MARIPIPI W E S T E R N S A M A R B I L I R A N SAN JULIAN KAWAYAN SAN SEBASTIAN ZUMARRAGA HINABANGAN CULABA ALMERIA CALBIGA E A S T E R N S A M A R NAVAL DARAM CITY OF BORONGAN CAIBIRAN PINABACDAO BILIRAN TALALORA VILLAREAL CALUBIAN CABUCGAYAN SANTA RITA BALANGKAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BABATNGON ISIDRO BASEY BARUGO LLORENTE LEYTE SAN HERNANI TABANGO MIGUEL CAPOOCAN ALANGALANG MARABUT BALANGIGA TACLOBAN GENERAL TUNGA VILLABA CITY MACARTHUR CARIGARA SALCEDO SANTA LAWAAN QUINAPONDAN MATAG-OB KANANGA JARO FE PALO TANAUAN PASTRANA ORMOC CITY GIPORLOS PALOMPON MERCEDES DAGAMI TABONTABON JULITA TOLOSA GUIUAN ISABEL MERIDA BURAUEN DULAG ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA L E Y T E MACARTHUR JAVIER (BUGHO) CITY OF BAYBAY ABUYOG MAHAPLAG INOPACAN SILAGO HINDANG SOGOD Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN BATO per Municipality SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary MATALOM SAN JUAN TOMAS (CABALIAN) OPPUS Municipality boundary MALITBOG S O U T H E R N L E Y T E Ongoing rehabilitation Ongoing MAASIN CITY activites LILOAN MACROHON PADRE BURGOS SAN 1-30 Planned FRANCISCO SAN 30-60 RICARDO LIMASAWA PINTUYAN 60-90 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters 0 325 K650 975 1,300 1,625 90-121 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES AS OF 24th Mar 2014 Early Food Sec. -

Pwds, Elderly Covered in SL Health Care

Comelec, PNP, DPWH to form “Oplan Baklas” A province-wide operation to remove election campaign materials not placed in designated common poster areas will be undertaken as soon as the “Oplan Baklas” will be formally fielded. The Commission on Elections (Comelec) serves as the lead agency March 16-31, 2016 of the activity, supported by the De- Media Center, 2nd Flr., Capitol Bldg. Vol. III, No. 18 partment of Public Works and High- ways-Southern Leyte District Engi- neering Office (DPWH-SLDEO) for PWDs, elderly covered in SL health care the 15-man manpower crew, and el- By Bong Pedalino OSCA seeks payout ements of the Philippine National Po- The provincial government of Southern Leyte takes care of hospital- of social pension to lice (PNP) for security. 860 senior citizens District Engr. Ma. Margarita Junia ization costs in case resident Senior Citizens and persons with disabilities (PWDs) would be admitted in any of the public hospitals managed by the confirmed during the Action Center By Erna Sy Gorne province. will be absorbed using the indigency Cable TV program last week that her The Office of the Senior Cit- office was one of those tapped by the This was made possible through fund set aside for this purpose from an ordinance passed by the Sang- the provincial coffers. izens Affairs (OSCA) in Maasin Comelec for the task. City seeks to complete the require- guniang Panlalawigan in its regular Another source of the indigency For now she is awaiting the call of ments for the hundreds of indigent session on October 12, 2015, and ap- fund that can be utilized was from the the Comelec for the operation to take senior citizens needed to payout proved for implementation by Gov. -

List of Establishments Where LHP, CLES and LEGS Were Conducted in CY 2017

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Regional Office No. VIII Tacloban City List of Establishments where LHP, CLES and LEGS were conducted in CY 2017 1. LHP NAME OF ESTABLISHMENT ADDRESS 1 TECHIRON Guiuan E. Samar 2 RED DAVE SECURITY AGENCY Brgy. San Roque, Biliran, Biliran 3 JRD GLASS SUPPLY Borongan City 4 EMCOR Borongan City 5 Jollibee Borongan City 6 J & C Lucky Mgt. & Devt., Inc. Borongan City 7 Zhanlin Marketing Borongan City 8 J Marketing Borongan City 9 Employees Union/Association (LGU-Julita) Julita, Leyte 10 Philippine Airline DZR Airport, San Jose, Tacloban City 11 Laoang Businesses Laoang, Northern Samar 12 Catarman Businesses Catarman, Northern Samar 13 Big 8 Finance Corporation Abgao Maasin city 14 Go Cash Lending Investor Abgao Maasin City 15 Assets Credit and Loan Tunga-Tunga Maasin City 16 J Marketing Maasin City 17 Nickel Collection and Lending Investor Kangleon St. Abgao Maasin City 18 Metro Global Tacloban City 19 Golden Lion Foods (Maasin)Corp.Jollibee Tunga-tunga Maasin City 20 J & F Department Store Maasin City 21 My Food Resources Inc. (Mang Inasal) Tagnipa, Maasin City 22 Coen Fashion and General Merchandise Abgao, Maasin City 23 Goodland Rice Mill Catarman, N. SAmar 24 Zopex Construction Catarman, N. SAmar 25 J&C Lucky 99 Store Catarman, N. SAmar 26 SH Dine In Catarman, N. SAmar 27 Jet Trading Catarman, N. SAmar 28 R8 Distribution Ormoc City 29 Arbee's Bakeshop Ormoc City 30 Phil. Oppo Mobile Ormoc City 31 Pmpc Ormoc City 32 IBMPC Ormoc City 33 Generika Drugstore Ormoc City 34 Mayong’s Bakeshop Ormoc City 35 Palawan Pawnshop Ormoc City 36 Ade-Da-Didi Ormoc City 37 Montery Ormoc City 38 Cecile Cont. -

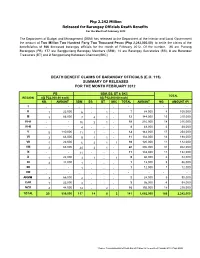

SUMMARY of RELEASES Php 2.242 Million Released for Barangay

Php 2.242 Million Released for Barangay Officials Death Benefits For the Month of February 2012 The Department of Budget and Management (DBM) has released to the Department of the Interior and Local Government the amount of Two Million Two Hundred Forty Two Thousand Pesos (Php 2,242,000.00) to settle the claims of the beneficiaries of 166 deceased barangay officials for the month of February 2012. Of the number, 25 are Punong Barangays (PB), 177 are Sangguniang Barangay Members (SBM), 14 are Barangay Secretaries (BS), 8 are Barangay Treasurers (BT) and 2 Sangguniang Kabataan Chairmen(SKC). DEATH BENEFIT CLAIMS OF BARANGAY OFFICIALS (E.O. 115) SUMMARY OF RELEASES FOR THE MONTH FEBRUARY 2012 PB SBM, BS, BT & SKC TOTAL REGION (@ P22,000.00 each) (@ P12,000.00 each) NO. AMOUNT SBM BS BT SKC TOTAL AMOUNT NO. AMOUNT (P) I - - - - - - - - - - II 1 22,000 6 - 1 - 7 84,000 8 106,000 III 3 66,000 7 4 1 - 12 144,000 15 210,000 IV-A - - 15 2 1 - 18 216,000 18 216,000 IV-B - - 4 - - - 4 48,000 4 48,000 V 5 110,000 11 1 - - 12 144,000 17 254,000 VI 3 66,000 9 1 1 - 11 132,000 14 198,000 VII 1 22,000 6 2 1 1 10 120,000 11 142,000 VIII 3 66,000 24 3 1 - 28 336,000 31 402,000 IX - - 11 - - - 11 132,000 11 132,000 X 1 22,000 3 1 - 1 5 60,000 6 82,000 XI 2 44,000 1 - - - 1 12,000 3 56,000 XII - - 1 - - - 1 12,000 1 12,000 XIII - - - - - - - - - - ARMM 3 66,000 2 - - - 2 24,000 5 90,000 CAR 1 22,000 3 - - - 3 36,000 4 58,000 NCR 2 44,000 14 - 2 - 16 192,000 18 236,000 TOTAL 25 550,000 117 14 8 2 141 1,692,000 166 2,242,000 *Source: Consolidated List of Death Benefit Claims for the month of February 2012 Php2.242M DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT (DILG) NATIONAL BARANGAY OPERATIONS OFFICE (NBOO) Consolidated List of Death Benefit Claims and Amount to be Paid to Barangay Oficials FEBRUARY 2012 NO. -

Total Total 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 21 0 1 0 24 94

PHILIPPINES: Summary of Completed Response Activities (as of 7 December 2013) Reg. Prov. Total IV-B Occidental Mindoro 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 Palawan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 VI Aklan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Antique 1 0 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 5 Capiz 9 4 3 80 14 0 0 0 21 131 Iloilo 5 1 9 29 0 0 0 0 0 44 Negros Occidental 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 VII Bohol 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cebu 4 0 33 44 0 1 0 0 24 106 VIII Eastern Samar 3 0 120 14 0 0 1 222 94 454 Leyte 4 71 220 69 14 0 11 115 150 654 Northern Samar 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Samar 5 0 0 5 0 0 1 0 40 51 Southern Leyte 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Total 34 76 385 247 28 1 13 337 331 1452 Affected Persons (in thousands) 0 - 250 250-500 500-750 750-1,000 > 1,000 The numbers above represent the number of activties in a sector (or in some cases, subsector) by province. The figures above are almost certainly incomplete. Nevertheless the sectoral and geographic coverage shown above can be considered indicative of the overall response. The Province names are colored based on the number of people affected as reported in the DSWD DROMIC database. -

Company Registration and Monitoring Department

Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance Securities and Exchange Commission SEC Building, EDSA, Greenhills, Mandaluyong City Company Registration and Monitoring Department LIST OF CORPORATIONS WITH APPROVED PETITIONS TO SET ASIDE THEIR ORDER OF REVOCATION SEC REG. HANDLING NAME OF CORPORATION DATE APPROVED NUMBER OFFICE/ DEPT. A199809227 1128 FOUNDATION, INC. 1/27/2006 CRMD A199801425 1128 HOLDING CORPORATION 2/17/2006 CRMD 3991 144. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL INC. 2/27/2009 CRMD 12664 18 KARAT, INC. 11/24/2005 CRMD A199906009 1949 REALTY CORPORATION 3/30/2011 CRMD 153981 1ST AM REALTY AND DEVLOPMENT CORPORATION 5/27/2014 CRMD 98097 20th Century Realty Devt. Corp. 3/11/2008 OGC A199608449 21st CENTURY ENTERTAINMENT, INC. 4/30/2004 CRMD 178184 22ND CENTURY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 7/5/2011 CRMD 141495 3-J DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 2/3/2014 CRMD A200205913 3-J PLASTICWORLD & DEVELOPMENT CORP. 3/13/2014 CRMD 143119 3-WAY CARGO TRANSPORT INC. 3/18/2005 CRMD 121057 4BS-LATERAL IRRIGATORS ASSN. INC. 11/26/2004 CRMD 6TH MILITARY DISTRICT WORLD WAR II VETERANS ENO9300191 8/16/2004 CRMD (PANAY) ASSOCIATION, INC. 106859 7-R REALTY INC. 12/12/2005 CRMD A199601742 8-A FOOD INDUSTRY CORP. 9/23/2005 CRMD 40082 A & A REALTY DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES, INC. 5/31/2005 CRMD 64877 A & S INVESTMENT CORPORATION 3/7/2014 CRMD A FOUNDATION FOR GROWTH, ORGANIZATIONAL 122511 9/30/2009 CRMD UPLIFTMENT OF PEOPLE, INC. (GROUP) GN95000117 A HOUSE OF PRAYER FOR ALL NATIONS, INC. CRMD AS095002507 A&M DAWN CORPORATION 1/19/2010 CRMD A. RANILE SONS REALTY DEVELOPMENT 10/19/2010 CRMD A.A. -

Region 8 Households Under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950

Philippines: Region 8 Households under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950 Lavezares Laoang Palapag Allen 2174 Rosario San Jose 5259 2271 1519 811 1330 San Roque Pambujan Mapanas Victoria Capul 1459 1407 960 1029 Bobon Catarman 909 San Antonio Mondragon Catubig 1946 5978 630 2533 1828 Gamay San Isidro Northern Samar 2112 2308 Lapinig Lope de Vega Las Navas Silvino Lobos 2555 Jipapad 602 San Vicente 844 778 595 992 Arteche 1374 San Policarpo Matuguinao 1135 Calbayog City 853 Oras 11265 2594 Maslog Calbayog Gandara Dolores ! 2804 470 Tagapul-An Santa Margarita San Jose de Buan 2822 729 1934 724 Pagsanghan San Jorge Can-Avid 673 1350 1367 Almagro Tarangnan 788 Santo Nino 2224 1162 Motiong Paranas Taft 1252 2022 Catbalogan City Jiabong 1150 4822 1250 Sulat Maripipi Samar 876 283 San Julian Hinabangan 807 Kawayan San Sebastian 975 822 Culaba 660 659 Zumarraga Almeria Daram 1624 Eastern Samar 486 Biliran 3934 Calbiga Borongan City Naval Caibiran 1639 2790 1821 1056 Villareal Pinabacdao Biliran Cabucgayan Talalora 2454 1433 Calubian 588 951 746 2269 Santa Rita Maydolong 3070 784 Basey Balangkayan Babatngon 3858 617 1923 Leyte Llorente San Miguel Hernani Tabango 3158 Barugo 1411 1542 595 2404 1905 Tacloban City! General Macarthur Capoocan Tunga 7531 Carigara 1056 2476 367 2966 Alangalang Marabut Lawaan Balangiga Villaba 3668 Santa Fe Quinapondan 1508 1271 800 895 2718 Kananga Jaro 997 Salcedo 2987 2548 Palo 1299 Pastrana Giporlos Matag-Ob 2723 1511 902 1180 Leyte Tanauan Mercedes Ormoc City Dagami 2777 326 Palompon 6942 2184 Tolosa 1984 931 Julita Burauen 1091 -

Biodiversity Baseline Assessment in the REDD-Plus Pilot and Key Biodiversity Area in Mt

Biodiversity baseline assessment in the REDD-Plus pilot and key biodiversity area in Mt. Nacolod, Southern Leyte Final technical report in collaboration with Imprint This publication is by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH through the Climate-relevant Modernization of the National Forest Policy and Piloting of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) Measures Project in the Philippines, funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) under its International Climate Initiative. The BMU supports this Initiative based on a decision of the German Parliament. For more information, see http://www.international-climate-initiative.com. As a federally owned enterprise, GIZ supports the German Government in achieving its objectives in the field of international cooperation for sustainable development. This study was undertaken by Fauna & Flora International commissioned by GIZ, with co-financing by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)- Global Environmental Facility (GEF)-DENR Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) New Conservation Areas in the Philippines Project (NewCAPP) and the Foundation for the Philippine Environment (FPE). Statements from named contributors do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. Data and information generated from the study are within the possession of the Philippine Government through the DENR as mandated by law. Published by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Registered offices Bonn and Eschborn, Germany T +49 228 44 60-0 (Bonn) T +49 61 96 79-0 (Eschborn) Responsible For. Ricardo L. Calderon Director Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Forest Management Bureau Forest Management Bureau Building Visayas Avenue, Quezon City 1101 Philippines T: 63 2 928 9313 / 927 4788 F: 63 2 920 0374 Dr. -

Adaptation of Community and Households to Climate – Related Disaster

Note: Note: Adaptation of Community and Households to Climate – Related Disaster The Case of Storm Surge and Flooding Experience in Ormoc and Cabalian Bay, Philippines Canesio Predo January, 2010 [Type the author name] [Type the company name] Economy and Environment Program for[Pick Southeast the date] Asia Climate Change Technical Reports WHAT IS EEPSEA? The Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia was established in May 1993 to support training and research in environmental and resource economics. Its goal is to strengthen local capacity in the economic analysis of environmental problems so that researchers can provide sound advice to policy-makers. The program uses a networking approach to provide financial support, meetings, resource persons, access to literature, publication avenues, and opportunities for comparative research across its nine member countries. These are Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, China, and Papua New Guinea. EEPSEA’s structure consists of a Sponsors Group, comprising all donors contributing at least USD 100,000 per year, an Advisory Committee of senior scholars and policy- makers, and a secretariat in Singapore. EEPSEA is a project administered by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) on behalf of the Sponsors Group. EEPSEA TECHNICAL REPORTS EEPSEA Technical Reports include studies that are either too academic and/or technical for wider circulation. It also includes research work that are based on short-term inquiries on specific topics (e.g. case studies) and those that are already published as part of EEPSEA special publications (e.g. books). Adaptation of Community and Households to Climate-Related Disaster The Case of Storm Surge and Flooding Experience in Ormoc and Cabalian Bay, Philippine and Canesio Predo ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors would like to thank the Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA) and the International Development Research Center (IDRC) for providing funding support to this project. -

PHI: Southern Leyte Landslide Disaster Assistance Project (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction)

Implementation Completion Memorandum Project Number: 40217 Grant Number: 9102-PHI November 2009 PHI: Southern Leyte Landslide Disaster Assistance Project (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) 1 JAPAN FUND FOR POVERTY REDUCTION (JFPR) IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION MEMORANDUM (ICM) I. BASIC INFORMATION 1. JFPR Number and Name of Grant: JFPR 9102-PHI: Southern Leyte Landslide Disaster Assistance Project 2. Country (DMC): 3. Approved JFPR Grant Amount: Philippines $3,000,000 4. Grant Type: 5-A. Undisbursed Amount 5-B. Utilized Amount X Project /X Capacity Building $245,165.08 $2,754,834.92 6. Contributions from other sources Source of Contribution: Committed Amount Actual Remark - Notes: Contributions1: DMC Government $ 173,910 $ 176,000 Other Donors (please name) --- --- Private Sector --- --- Community/Beneficiaries $ 11,250 $ 1,240 7-A. GOJ Approval Date: 7-B. ADB Approval Date: 7-C. Date the LOA was signed 15 November 2006 15 December 2006 (Grant Effectiveness Date): 15 December 2006 8-A. Original Grant Closing Date: 8-B. Actual Grant Closing Date: 8-C. Account Closing Date: 31 July 2009 31 July 2009 8 December 2009 9. Name and Number of Counterpart ADB (Loan) Project: N/A 10. The Grant Recipient(s): Hon. Gov. Damian G. Mercado Provincial Government of Southern Leyte Maasin City, Southern Leyte, Philippines Email: [email protected] Tel.: (053) 570-9018; Fax: (053) 570-9016 11. Executing and Implementing Agencies: Provincial Government of Southern Leyte was the Executing and Implementing Agency for the Project. Hon. Gov. Damian G. Mercado Provincial Government of Southern Leyte Maasin City, Southern Leyte, Philippines Email: [email protected] Tel.: (053) 570-9018; Fax: (053) 570-9016 Ms. -

EXPLANATORY NOTE the First District of Leyte Coniprises The

13THCONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC ) OF THE PHILIPPINES 1 Third Regular Session 1 Introduced by Senator Ralph G. Recto EXPLANATORY NOTE The First District of Leyte coniprises the Municipalities of Alangalang, Babatngon, Palo, San Miguel, Sta. Fe, Tanaua, Tolosa and the City ofTacloban, the capital ofthe province and the acknowledged Regional Center of Region 8. The request for two additional branches is to address the growing demand for the immediate resolution of cases which presently clog the docklets and slow down the dispensation of justice in the area. The Leyteiios deserve expenditous resolutions of their legal problems. The density of cases being distributed among the five (5) courts is contributory to the slow disposition of cases and to the administration of justice in general. Hence, this bill seeks to create two (2) additional Regional Trial Court branches in the Eighth Judicial Region in Eastern Visayas, particularly in the City of Tacloban, Province of Leyte, in addition to the five (5) branches thereof in the First District ofthe aforementioned province. It is hoped that this proposal will greatly reduce the burden of the existing courts. In view thereof, the immediate passage of this bill is 13THCONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC ) OF THE PHILIPPINES 1 Third Regular Session ) Introduced by Senator Ralph G. Recto AN ACT CREATING TWO ADDITIONAL REGIONAL TFUAL COURT BRANCHES IN THE PROVINCE OF LEYTE TO BE STATIONED IN THE CITY OF TACLOBAN, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE SECTION 14, PARAGRAPH (I) OF BATAS PAMBANSA BLG. 129, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE JUDICIARY REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1980, AS AMENDED, AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR Be enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled: SECTION 1. -

1 Nutrition Cluster Weekly Update – 19

NUTRITION CLUSTER WEEKLY UPDATE – 19. February 2014 Region VIII- East Visayas, Philippines, Co-Leads: National Nutrition Council/DoH Region VIII and UNICEF Partners ACF, ACTED, Arugaan, BRMFI (Bukidnon Resource Management Foundation Inc), ChildFund, HOM (Health Organisation of Mindanao), NNC/DoH (National Nutrition Council/Department of Health), IFRC, IMC, MDM, Mercy in Action, MSF, Plan International, Samaritan's Purse, Save the Children, UNICEF, WFP, WHO and World Vision International. Needs The Nutrition Cluster in Region VIII aims to target 71,000 boys and girls under five years of age and 66,000 pregnant and lactating women (PLW). Priority areas of intervention include: (i) protection and promotion of appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices for 90,500 pregnant women and children aged 0-23 months; (ii) prevention of vitamin and mineral deficiencies with provision of fortified high energy biscuits to 51,455 children aged 24-59 months and micronutrient powders to 71,000 children aged 6-59 months; (iii) prevention of acute malnutrition with blanket supplementary feeding for 25,700 children aged 6-23 months; (iv) treatment of 1,565 children aged 6-59 months with severe acute malnutrition; (v) management of moderate acute malnutrition for 4,700 children aged 6- 59 months and 2,500 PLW, and (vi) timely nutrition surveillance. The targets as defined in the Strategic Response Plan will be recalibrated when the results of the SMART methodology nutrition assessment results are available in late March. Response in Leyte Community Management of Acute Malnutrition In the past week, 5,277 children have been screened and reported, identifying 5 new cases of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) and 22 cases of Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM).Five new children were admitted to Outpatient Treatment Program (OTP for SAM treatment); 24 children were admitted to Targeted Supplementary Feeding Program (tSFP for MAM treatment) and there were no admissions to Inpatient Treatment Program (IPT).