Politics of Informal Retail in the Neoliberal Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE GOD THAT IS FAILING-I Bibekananda Ray

Frontier Vol. 43, No. 17, November 7-13, 2010 THE GOD THAT IS FAILING-I Bibekananda Ray In November 1949 came out a book in the USA that brought to the ken of the non-communist world the disillusion about communism of six renowned Western writers. Called 'The god that failed', it was an anthology of experiences of communist society of Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Si-lone, Richard Wright, Andre Gide, Louis Fischer and Stephen Spender who became ardent members of communist parties of their respective countries- Germany, Italy, USA, France and Britain, but quit out of frustration. It became an instant best-seller for its revelation of the workings of communist parties and governments of five countries. Alfred Hitchcock's 'Torn Curtain' (1966) was a celluloid revelation of the same in East Germany. This disillusion became a deja vous in works of many other writers and artists in countries where communism thrived. In Soviet Russia, two great writers–Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) shocked readers with the persecution and honors that their protagonists experienced in two novels—Dr Zhivago (1957) and Gulag Archipelago (1973), the second a trilogy, describing a forced labour camp for dissidents in Siberia, which fetched them Nobel Prizes in literature in 1958 and 1970. A German writer, Herta Muller, awarded Nobel Prize in 2009, revealed to the world through her poems, novels and essays the oppressive regime of President Nicolae Ceauses of Romania where she was born. Ayn Rand was equally frank about the effects of communism in Germany in "We the Living'. -

India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings

All India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings Q1: In whatever financial condition you are placed today, on the whole are you satisfied or dissatisfied with it? N (%) 1: Fully satisfied 4937 20.4 2: Somewhat satisfied 11253 46.4 3: Somewhat dissatisfied 3777 15.6 4: Fully dissatisfied 3615 14.9 7: Can't say 428 1.8 8: No response 225 .9 Total 24235 100.0 Q2: As compared to five years ago, how is the economic condition of your household today – would you say it has become much better, better, remained same, become worse or much worse? N (%) 1: Much better 2280 9.4 2: Better 7827 32.3 3: Remained Same 10339 42.7 4: Worse 2446 10.1 5: Much worse 978 4.0 7: Can't say 205 .8 8: No response 159 .7 Total 24235 100.0 Q3: Many people talk about class nowadays, and use terms such as lower class, middle class or upper class. In your opinion, compared to other households, the household you live in currently belongs to which class? N (%) 1: Lower class 5933 24.5 2: Middle class 13459 55.5 3: Upper Class 1147 4.7 6: Poor class 1741 7.2 CSDS, LOKNITI, DELHI Page 1 All India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings 7: Can't say 254 1.0 8: No response 1701 7.0 Total 24235 100.0 Q4: From where or which medium do you mostly get news on politics? N (%) 01: Television/TV news channel 11841 48.9 02: Newspapers 2365 9.8 03: Radio 247 1.0 04: Internet/Online news websites 361 1.5 05: Social media (in general) 400 1.7 06: Facebook 78 .3 07: Twitter 59 .2 08: Whatsapp 99 .4 09: Instagram 19 .1 10: Youtube 55 .2 11: Mobile phone 453 1.9 12: Friends/neighbours 695 2.9 13: -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 9th of July, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 09-07-2021 1 1 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 09-07-2021 2 4 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB-III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 16 On 09-07-2021 3 57 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 17 On 09-07-2021 4 66 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 09-07-2021 5 68 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB - V At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 30 On 09-07-2021 6 74 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB-VI At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 09-07-2021 7 80 HON'BLE JUSTICE BISWAJIT BASU DB-VII At 11:00 AM 5 On 09-07-2021 8 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 89 SB At 11:00 AM 8 On 09-07-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 94 SB II At 11:00 AM 9 On 09-07-2021 10 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 116 SB - III At 11:00 AM 13 On 09-07-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 124 SB - IV At 11:00 AM 7 On 09-07-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 150 SB - V At 11:00 AM 26 On 09-07-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

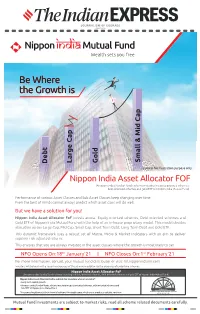

Be Where the Growth Is Be Where the Growth Is

Be Where the Growth is Small & Mid Cap Large Cap Gold Debt Visual is for illustration purpose only. Nippon India Asset Allocator FOF (An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund) Performance of various Asset Classes and Sub Asset Classes keep changing over time. Even the best of minds cannot always predict which asset class will do well. But we have a solution for you! Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF invests across Equity oriented schemes, Debt oriented schemes and Gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund with the help of an in-house proprietary model. This model decides allocation across Large Cap, Mid Cap, Small Cap, Short Term Debt, Long Term Debt and Gold ETF. This dynamic framework uses a robust set of Macro, Micro & Market Indicators with an aim to deliver superior risk adjusted returns. This ensures that you are always invested in the asset classes where the growth is most likely to be! NFO Opens On:18th January'21 | NFO Closes On:1st February'21 For more information, contact your mutual fund distributor or visit: mf.nipponindiaim.com Investors will be bearing the recurring expenses of the scheme in addition to the expenses of underlying schemes. Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF (An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund) Nippon India Asset Allocator FoF is suitable for investors who are seeking*: • Long term capital growth • An open ended fund of funds scheme investing in equity oriented schemes, debt oriented schemes and Gold ETF of Nippon India Mutual Fund Investors understand that their principal *Investors should consult their financial advisors if in doubt about whether the product is suitable for them. -

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 Head of the Department

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 CHAPTER II DEPARTMENT OF BENGALI Head of the Department : SIBABRATA CHATTOPADHYAY Teaching Staff : (as on 31.05.2013) Professor : Dr. Krishnarup Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Asish Kr. Dey, M.A., Ph.D Dr Amitava Das, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Sibabrata Chattopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arun Kumar Ghosh, M.A., Ph.D Dr Uday Chand Das, M.A., Ph.D Associate Professor : Dr Ramen Kr Sar, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arindam Chottopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr Anindita Bandyopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Alok Kumar Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Assistant Professor : Ms Srabani Basu, M.A. Field of Studies : A) Mediaval Bengali Lit. B) Fiction & Short Stories, C) Tagore Lit. D) Drama Student Enrolment: Course(s) Men Women Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total MA/MSc/MCom 1st Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 2nd Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 3rd Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 4th Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 M.Phil 01 01 01 01 02 02 01 03 Research Activities :(work in progress) Sl.No. Name of the Scholar(s) Topic of Research Supervisor(s) 1. Anjali Halder Binoy Majumdarer Kabitar Nirmanshaily Prof Amitava Das 2. Debajyoti Debnath Unishsho-sottor paraborti bangla akhayaner dhara : prekshit ecocriticism Prof Uday Chand Das 3. Prabir Kumar Baidya Bangla sahitye patrikar kromobikas (1851-1900) Dr.Anindita Bandyopadhyay 4. -

Farmerprotestsflare Upagain,Manyinjured Inharyanacrackdown

eye THE SUNDAY EXPRESS MAGAZINE In the Light of Ye sterday KOLKATA,LATECITY Once there wasaKabul that AUGUST29,2021 wasacityofdreamersand 18PAGES,`5.00 poets, kite flyersand (EX-KOLKATA`7,`12INNORTHEASTSTATES&ANDAMAN) children trudging to school DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM PAGES 13, 14, 15 ED summons BKU ISSUES CALL TO FARMERS TO GATHER to Abhishek, wife; Mamata Farmerprotestsflare says agencies upagain,manyinjured ‘let loose’ inHaryanacrackdown Lathicharge on protestagainsta Abhishek,Rujiraare facing a BJP meetchaired moneylaundering case by CM; Khattar says if violence, EXPRESSNEWSSERVICE NEWDELHI,KOLKATA, ‘police have to act’ AUGUST28 THE ENFORCEMENT Directorate EXPRESSNEWSSERVICE (ED) has summonedsenior Afghans queue up forone of Italy’s lastmilitaryaircraftout of Kabul, Friday. Italysaid it had evacuated 4,890 people in all. Reuters CHANDIGARH,AUGUST28 Trinamool Congress leader and Chief MinisterMamata THE AGITATION againstfarm Police break up the protestatBastara toll plaza, Karnal. Express Banerjee’s nephewAbhishek laws enacted lastyear returned Banerjee and his wifeRujirafor First outreach signal: UNSC drops to the spotlight Saturdaywhen questioning in connection with a Haryana Police crackeddownon case of moneylaundering asso- farmers in Karnal, leaving sev- If someone breaches ciated with alleged pilferageof eral injured in alathicharge at coal from Eastern Coalfield Taliban reference in line on terror the Bastara toll plaza on the na- cordon, make sure has a Limited mines. tional highway. Abhishek,anMPfrom The farmers were protesting Diamond Harbour,has been India chair,itmentionedTaliban on Aug16; onlytalksofAfghan groups Aug27 againstaBJP meeting on the broken head: IAS officer asked to appear before the forthcoming panchayatpolls — Investigating Officer on ity as the chair forthis month. -

Hawkers' Movement in Kolkata, 1975-2007

NOTES hawkers’ cause. More than 32 street-based Hawkers’ Movement hawker unions, with an affiliation to the mainstream political parties other than the in Kolkata, 1975-2007 ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), better known as CPI(M), constitute the body of the HSC. The CPI(M)’s labour wing, Centre Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), has a hawk- er branch called “Calcutta Street Hawkers’ In Kolkata, pavement hawking is n recent years, the issue of hawkers Union” that remains outside the HSC. The an everyday phenomenon and (street vendors) occupying public space present paper seeks to document the hawk- hawkers represent one of the Iof the pavements, which should “right- ers’ movement in Kolkata and also the evo- fully” belong to pedestrians alone, has lution of the mechanics of management of largest, more organised and more invited much controversy. The practice the pavement hawking on a political ter- militant sectors in the informal of hawking attracts critical scholarship rain in the city in the last three decades, economy. This note documents because it stands at the intersection of with special reference to the activities of the hawkers’ movement in the city several big questions concerning urban the HSC. The paper is based on the author’s governance, government co-option and archival and field research on this subject. and reflects on the everyday forms of resistance (Cross 1998), property nature of governance. and law (Chatterjee 2004), rights and the Operation Hawker, 1975 very notion of public space (Bandyopadhyay In 1975, the representatives of Calcutta 2007), mass political activism in the context M unicipal Corporation (henceforth corpora- of electoral democracy (Chatterjee 2004), tion), Calcutta Metropolitan Development survival strategies of the urban poor in the Authority (CMDA), and the public works context of neoliberal reforms (Bayat 2000), d epartment (PWD) jointly took a “decision” and so forth. -

Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay: Archiving from Below

Archiving from Below: The Case of the Mobilised Hawkers in Calcutta by Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay University of California, Berkeley and Jadavpur University Sociological Research Online 14(5)7 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/5/7.html> doi:10.5153/sro.2008 Received: 17 Mar 2009 Accepted: 4 Oct 2009 Published: 30 Nov 2009 Abstract In the last two decades or more, critical scholarship in the human sciences has been commenting on different aspects of the 'archive'. While much has been said on the archive of the state, especially in the historiography of colonial South Asia, very little is known about the archival functions of political parties, movements, grassroots community organisations, and trade unions that are involved in the governance of populations in the post-colonial state. The paper argues that archival claims lie at the heart of negotiations between the state and population groups. It looks at the archival function of the Hawker Sangram Committee (HSC) in Calcutta to substantiate the point. Following Operation Sunshine (1996), a move by the state to forcibly evict hawkers from some selected pavements of Calcutta, in order to reclaim such 'public' spaces, a mode of collective resistance developed under the banner of the HSC. The HSC has subsequently come to occupy a central position in the governance of the realm of pavement-hawking through the creation and maintenance of an archival database that articulates the entrepreneurial capacity of the 'poor hawker' and his ability to deliver goods and services at low-cost. The significance of the HSC's archive is that, it enables the organisation to form a moral and rational critique of the exclusionary discourses on the hawker, mostly propagated by a powerful combination of a few citizens' associations, the judiciary and the press. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Monday, 21st of December, 2020 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 21-12-2020 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE SANJIB BANERJEE 16 On 21-12-2020 2 2 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE DB At 12:15 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SANJIB BANERJEE 16 On 21-12-2020 3 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE MOUSHUMI BHATTACHARYA DB At 03:30 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 21-12-2020 4 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 12:45 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 21-12-2020 5 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 21-12-2020 6 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 21-12-2020 7 20 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 12:55 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 21-12-2020 8 21 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE JOYMALYA BAGCHI 28 On 21-12-2020 9 24 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VI At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 5 On 21-12-2020 10 38 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - VII At 10:45 AM 5 On 21-12-2020 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 40 SB At 03:00 PM 25 On 21-12-2020 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 44 SB - I At 10:45 AM 4 On 21-12-2020 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 54 SB - II At 10:45 AM 6 On 21-12-2020 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 65 SB At 03:30 PM 38 On 21-12-2020 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE ASHIS KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 69 SB - IV At 10:45 AM 30 On 21-12-2020 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 73 SB - V At 10:45 AM 13 On 21-12-2020 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 77 SB - VI At 10:45 AM SL NO. -

Interruptions) SHRI PRIYA RANJAN DASMUNSI (RAIGANJ): Sir, My Issue Is Regarding the Budget Itself

nt> 11.05 hrs. RULING BY SPEAKER RE : PROPRIETY OF (I) TERMING ''''VOTE-ON-ACCOUNT'''' AS INTERIM BUDGET IN THE ORDER PAPER OF THE DAY; AND OF CONVENING OF THE SESSION OF THE YEAR ON 29 JANUARY, 2004 WITHOUT THE PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Title: Regarding propriety of terming "Vote on Account" as the "Interim Budget" in the Order Paper of the day; and convening of the first session of the year on 29 January, 2004 without the Presidential Address. (The point of order disallowed). SHRI SOMNATH CHATTERJEE (BOLPUR): Sir, I have given notice on a very important issue. I would like your kind permission to raise it. MR. SPEAKER: Before you speak, let me remind the House that, in the Business Advisory Committee, it was decided that we would start today with the presentation of the Budget at 11 o'clock and after the Budget, we would be taking up the `Zero Hour' at 12 noon. I would request the hon. Members that their issues are no doubt important ones and, therefore, I would be definitely taking up their issues, the issues which Shri Dasmunsi and Shri Somnath Chatterjee want to raise, during the `Zero Hour'. Both the issues can be discussed by giving priority in the `Zero Hour'. ...(Interruptions) SHRI PRIYA RANJAN DASMUNSI (RAIGANJ): Sir, my issue is regarding the Budget itself. It cannot be taken up after the presentation of the Budget. It is on the very constitutional matter pertaining to the procedure of the House.....(Interruptions) It is not a `Zero Hour' issue. It is on the procedure of the House. -

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4.