Bingo Playing and Problem Gambling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaming Statutes

All Gambling is Illegal Unless Specifically Excluded from Illegality. Gambling is defined in Arizona Revised Statutes (“A.R.S.”) § 13-3301(4) to require risking something of value for an opportunity to win a benefit, which is awarded by chance. As provided by A.R.S. § 13-3302, all gambling is illegal in Arizona unless a statute excludes it as legal. Charitable organizations may qualify for an exclusion from illegal gambling by being licensed under A.R.S. § 5-504(I) for Arizona Lottery pull tab games, A.R.S. § 5-512 for all products of the Arizona Lottery, or by qualifying as a non profit for the conduct of raffles under A.R.S. § 13-3302(B). The statutes limit unlicensed charitable organizations to conducting raffles. All other forms of gambling are prohibited. Arizona statutes provide no definition of raffle, and no Arizona court has defined raffle. A raffle machine is required to follow the usual and ordinary definition of a raffle with the only difference being that it is played on a machine to qualify as a raffle machine. A second chance raffle drawing conducted after the conduct of Keno on a machine does not change the character of the Keno to a raffle. Each component must be authorized by law or it is illegal gambling. Arizona Liquor Law - A.R.S. §4-244. Unlawful acts It is unlawful: 26. For a licensee or employee to knowingly permit unlawful gambling on the premises. Arizona liquor law does not allow gambling at liquor-licensed businesses when the customer is required to pay for a chance to win something of value. -

Smokefree Casinos and Gambling Facilities

SMOKEFREE CASINOS AND GAMBLING FACILITIES SMOKEFREE MODEL POLICY AND IMPLEMENTATION TOOLKIT Smokefree Casinos and Gambling Facilities OCTOBER 2013 State-Regulated Gaming Facilities There are now more than 500 smokefree casinos and gambling facilities in the U.S. It is required by law in 20 states, a growing number of cities, and in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. In addition, a growing number of sovereign American Indian tribes have made their gambling jobsites smokefree indoors (see page 9). Note: This list does not include all off-track betting (OTB) facilities. To view a map of U.S. States and territories that require state-regulated gaming facilities to be 100% smokefree, go to www.no-smoke.org/pdf/100smokefreecasinos.pdf. Arizona Crystal Casino and Hotel ..........Compton Apache Greyhound Park ..........Apache Junction Club Caribe Casino ...............Cudahy Turf Paradise Racecourse .........Phoenix Del Mar ..........................Del Mar Rillito Park Race Track ............Tucson The Aviator Casino ................Delano Tucson Greyhound Park ..........Tucson St. Charles Place ..................Downieville Tommy’s Casino and Saloon. El Centro California Oaks Card Club ...................Emeryville Golden Gate Fields ................Albany S & K Card Room .................Eureka Kelly’s Cardroom .................Antioch Folsom Lake Bowl Nineteenth Hole ..................Antioch Sports Bar and Casino ............Folsom Santa Anita Park ..................Arcadia Club One Casino ..................Fresno Deuces Wild Casino -

A Solid Performance Strong Performance from Core Businesses Drive 2019 Results in Rapidly Evolving Industry

Financial highlights A solid performance Strong performance from core businesses drive 2019 results in rapidly evolving industry Revenue Adjusted EBITDA Regulated revenue €1,508m €383m 88% 2019 1,508 2019 383 2019 88 2018 1,225 2018 345 2018 80 2017 807 2017 322 2017 54 Operating cash flow Total shareholder returns €317m €120m 2019 317 2019 120 2018 385 2018 116 2017 307 2017 113 2 Playtech plc Annual Report and Financial Statements 2019 Operational highlights Significant Strategic Report Strategic operational progress Playtech had another busy year with new product launches, innovations, new customer wins and extended relationships with existing customers Governance Major new strategic Fortuna migrates Sportsbook onto Swiss Casinos partners with agreement with Wplay Playtech’s omni-channel platform Playtech to lead new online In November 2019 Playtech signed a major Playtech announced that Fortuna market in Switzerland deal with one of Colombia’s leading brands. Entertainment Group, the largest betting Swiss Casinos, which operates one of Under the agreement Playtech will become and gaming operator in Central and Eastern Switzerland’s largest casinos, Casino Zurich, Wplay’s strategic technology partner Europe, completed the migration of its became the latest major European operator Financial Statements delivering its omni-channel products together Sportsbook in Slovakia onto Playtech’s IMS to partner with Playtech in September 2019 with operational and marketing services platform. Fortuna customers can now in order to access its award-winning Casino across Wplay’s retail and online operations. seamlessly access Sportsbook funds and Live Casino offering. across retail and online, while Fortuna is Playtech has a track record of developing now able to harness Playtech’s Engagement Playtech’s Casino offering allows players to newly regulated online markets through the Centre and safer gambling tools across its access content anywhere, at any time and successful structured agreement with omni-channel offering. -

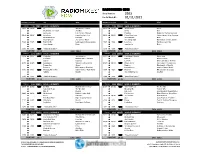

RADIOMIXES EDM Show Number: 2103 for Air Week Of: 01/11/2021

RADIOMIXES EDM Show Number: 2103 For Air Week Of: 01/11/2021 TALK TIMES (Count Down) TITLE ARTIST TALK TIMES (Count Down) TITLE ARTIST Filename: 2103 EDM1A HOUR 1, SEGMENT A Filename: 2103 EDM3A HOUR 3, SEGMENT A 23:55 - 23:40 0:15 Ily Surf Mesa f/ Emilee 23:23 - 23:08 0:15 The Business Tiesto 23:55 - 23:55 My Head & The Heart Ava Max 23:23 - 23:23 Ritmo BEP 23:55 - 23:55 Get Lucky Daft Punk f/ Pharrell 23:23 - 23:23 Paradise Meduza f/ Dermot Kennedy 14:50 - 14:34 0:16 Let's Love David Guetta f/ Sia 14:15 - 14:01 0:14 I Need Your Love Calvin Harris f/ Ellie Goulding 23:55 - 23:55 Break My Heart Dua Lipa 23:23 - 23:23 Goosebumps Hvme 23:55 - 23:55 Head & Heart Joel Corry f/ Mnek 23:23 - 23:23 One Thing Right Marshmello f/ Kane Brown 5:28 - 5:15 0:13 Rain On Me Lady Gaga f/ Ariana Grande 5:27 - 5:12 0:15 Let's Love David Guetta f/ Sia 23:55 - 23:55 Goosebumps Hvme 23:23 - 23:23 Supalonely Benee 23:55 - 23:55 23:23 - 23:23 0:20 - 0:00 0:20 *music bed outro* 0:30 - 0:00 0:30 *music bed outro* RUNTIME: 23:55 END: COLD RUNTIME: 23:23 END: COLD Filename: 2103 EDM1B HOUR 1, SEGMENT B Filename: 2103 EDM3B HOUR 3, SEGMENT B 23:29 - 23:14 0:15 Painkiller Joe Killington 23:12 - 22:57 0:15 Everything I Wanted Billie Eilish 23:29 - 23:29 Too Much Marshmello f/ Imanbek 23:12 - 23:12 Nobody Notd f/ Catello 23:29 - 23:29 Say So Doja Cat 23:12 - 23:12 Lovelife Benny Benassi f/ Jeremih 15:35 - 15:20 0:15 Lasting Love Sigala f/ James Arthur 15:13 - 14:58 0:15 House Arrest Sofi Tukker f/ Gorgon City 23:29 - 23:29 Trampoline Shaed 23:12 - 23:12 Happier Marshmello -

"UMF Radio" Channel to Launch on Siriusxm Live from Miami During Ultra Music Festival and Miami Music Week

"UMF Radio" Channel to Launch on SiriusXM Live from Miami during Ultra Music Festival and Miami Music Week Limited-run channel to broadcast live Ultra Music Festival performances by Afrojack, Armin van Buuren, Avicii, Bingo Players, Cazzette, David Guetta, Dirty South, Fatboy Slim, Fedde le Grand, Kaskade, Knife Party, Martin Solveig, Nicky Romero, R3hab, Sander van Doorn, Steve Aoki, Thomas Gold, W&W and more Tiesto to present a special live DJ set from the SiriusXM Music Lounge to celebrate the 1 year anniversary of his SiriusXM channel Tiesto's Club Life Radio SiriusXM's "UMF Radio" to feature live DJ sets by Armin van Buuren, Calvin Harris, Ferry Corsten, Hardwell, Krewella, Nicky Romero and Quintino from the SiriusXM Music Lounge in Miami NEW YORK, March 12, 2013 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) announced today that it will launch "UMF Radio," ("Ultra Music Festival Radio"), the limited-run, 24/7, commercial-free channel featuring performances, DJ sets and interviews with the world's most popular DJs, producers and international dance music artists from the Ultra Music Festival, the world famous outdoor electronic dance music festival. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO ) SiriusXM's "UMF Radio" will air on SiriusXM's Electric Area, channel 52, beginning Friday, March 15 at 12:00 pm ET. The limited-run channel will broadcast live DJ sets from both weekends of Ultra Music Festival, which is celebrating its 15 year anniversary, including Afrojack, Armin van Buuren, Avicii, Benny Benassi, Bingo Players, Borgore, Cazzette, Chuckie , David Guetta, Dirty South, Fatboy Slim, Fedde le Grand, Hardwell, Kaskade, Knife Party, Major Lazer, Martin Solveig, Markus Schulz, Nicky Romero, Quintino, R3hab, Sander van Doorn, Steve Aoki , Thomas Gold, Tritonal, W&W and more. -

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists Vom 16.11.2018 Hardwell HELMO

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists vom 16.11.2018 Hardwell 01. Shaun Frank & Hunter Siegel feat. Roshin - Shapes 02. Martin Garrix feat. Mike Yung - Dreamer (Jack & James X Danny Leax Remix) 03. Loris Cimino feat. Alice Berg - Shape Of My Regret (HARDWELL EXCLUSIVE) 04. Suyano & Astra - Brothers In Arms (HARDWELL EXCLUSIVE) 05. Stino - Feel Free 06. Robin Aristo - Get Down 07. Paris Blohm feat. Paul Aiden - Alive (MOST VOTED TRACK) 08. FTampa & Clocktape - EDM ROX (Club Mix) 09. Castion & Dylerz feat. NEAD - Take Me (COMMUNITY RELEASE #1) 10. Krimsonn & Ascade - Don't Wanna Be Cold (COMMUNITY RELEASE #2) 11. Dynoro & Gigi D'Agostino - In My Mind (MR.BLACK Remix) 12. Zinko & Stevie Krash - Rock (MOTi 'How About Now' Edit) 13. SWACQ - Parkour (Here We Go) 14. Maurice West - The Kick 15. Bassjackers vs Wolfpack - Zero Fs Given 16. Maddix feat. Kris Kiss - Shuttin It Down17. 18. FTampa & 22Bullets – Shahar HELMO 01. MARTIN GARRIX - HIGH ON LIFE 02. JASON DERULO - WANT TO WANT ME 03. DAVID GUETTA FEAT. BEBE REXHA & J BALVIN - SAY MY NAME 04. ARMIN VAN BUUREN - BLAH BLAH BLAH 05. KYGO FEAT. SANDRO CAVAZZA - HAPPY NOW 06. MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS FEAT. RAY DALTON - CAN'T HOLD US 07. NOTD & FELIX JAEHN - SO CLOSE 08. EL PROFESOR - CE SOIR? [HUGEL REMIX) 09. SIA FEAT. SEAN PAUL - CHEAP THRILLS 10. OFENBACH - PARADISE 11. LOST FREQUENCIES - LIKE I LOVE YOU 12. CLEAN BANDIT & DEMI LOVATO - SOLO 13. LOUD LUXURY FEAT. ANDERS - LOVE NO MORE 14. CALVIN HARRIS FEAT. FLORENCE WELCH - SWEET NOTHING 15. RITA ORA - LET YOU LOVE ME 16. DYNORO - IN MY MIND 17. -

Gambling Among the Chinese: a Comprehensive Review

Clinical Psychology Review 28 (2008) 1152–1166 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Psychology Review Gambling among the Chinese: A comprehensive review Jasmine M.Y. Loo a,⁎, Namrata Raylu a,b, Tian Po S. Oei a a School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia b Drug, Alcohol, and Gambling Service, Hornsby Hospital, Hornsby, NSW 2077, Australia article info abstract Article history: Despite being a significant issue, there has been a lack of systematic reviews on gambling and problem Received 23 November 2007 gambling (PG) among the Chinese. Thus, this paper attempts to fill this theoretical gap. A literature Received in revised form 26 March 2008 search of social sciences databases (from 1840 to now) yielded 25 articles with a total sample of 12,848 Accepted 2 April 2008 Chinese community participants and 3397 clinical participants. The major findings were: (1) Social gambling is widespread among Chinese communitiesasitisapreferredformofentertainment.(2) Keywords: Prevalence estimates for PG have increased over the years and currently ranged from 2.5% to 4.0%. (3) Gambling Chinese problem gamblers consistently have difficulty admitting their issue and seeking professional Chinese help for fear of losing respect. (4) Theories, assessments, and interventions developed in the West are Ethnicity Problem gambling currently used to explain and treat PG among the Chinese. There is an urgent need for theory-based Culture interventions specifically tailored for Chinese problem gamblers. (5) Cultural differences exist in Addiction patterns of gambling when compared with Western samples; however, evidence is inconsistent. Pathological gambling Methodological considerations in this area of research are highlighted and suggestions for further Review investigation are also included. -

Leading Edge

leading edge Annual report & accounts 2013 Introduction Strategic report We want to ‘let the world play for real’ 01 Financial snapshot 02 Our business by improving access to our games and 04 Investment case 08 Our business model and KPIs maximising their appeal – these are 10 CEO’s review Annual report & accounts 2013 key drivers of our revenue model. 16 Strategy 26 Markets and regulatory overview bwin.party 42 Business and financial review 2013 Our proprietary eCommerce platform 52 Principal risks differentiates us from our competitors 54 Focus on responsibility and gives us a leading edge as we Governance transition to regulated markets. We 58 Chairman’s statement 60 Board of Directors deliver world-leading gaming products 62 Corporate governance 83 2013 Directors’ and brands, across multiple channels Remuneration Report and markets to an increasingly 106 Other Directors’ Report Disclosures 109 Statement of Directors’ demanding customer base. responsibilities Financial performance A richer experience online 110 Independent Auditors’ Report View our online report where you 114 Consolidated statement on can see and hear about our strategy comprehensive income in action and thoughts about our 115 Consolidated statement of future at: www.bwinparty.com financial position 116 Consolidated statement of “ Based on our performance changes in equity to-date we expect to deliver 117 Consolidated statement year-on-year revenue growth of cashflows in 2014. With further cost 118 Notes to the consolidated savings to come and the financial statements -

MICHIGAN GAMING CONTROL BOARD Lucky's Poker Room

STATE OF MICHIGAN Rick Snyder MICHIGAN GAMING CONTROL BOARD Richard Kalm GOVERNOR DETROIT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR November 26, 2013 EMERGENCY ORDER OF SUMMARY SUSPENSION PENDING FURTHER INVESTIGATION Under Executive Order 2012-4, the Executive Director of the Michigan Gaming Control Board was transferred all authority, powers, duties, functions, records, and property of the Lottery Commissioner, and Bureau of State Lottery, related to the licensing and regulation of millionaire parties under the Bingo Act and its promulgated rules. MCL 432.101 et seq. In conformance with this obligation, the Executive Director has conducted an investigation at 6340 N. Genesee Road, Flint, Michigan which is a location known as Lucky’s Poker Room, Lucky’s Bingo Hall, Shamrock’s Tavern, and Shamrock Internet Café. The investigation remains pending, but it has already revealed material violations of state law, necessitating an emergency order of suspension of all licensed millionaire party events at this location. Section 16 of the Bingo Act (the Bingo Act), MCL 432.116, provides in part that a license may be summarily suspended for a period of not more than 60 days when the act and rules have been violated. Lucky's Poker Room, Lucky’s Bingo Hall, Shamrock’s Tavern, and Shamrock’s Café, Inc. (a.k.a. Shamrock’s Internet Café) are located at 6340 N. Genesee Rd. Flint, Michigan and have title ownership as Pine Meadows Plaza, LLC. Pine Meadows Plaza, LLC is owned by Michael Joubran. Thomas Joubran, son of Michael Joubran, is the resident agent for Shamrock’s Café, Inc. and the operator, resident agent and contact person for Lucky’s Poker Room and Lucky’s Bingo Hall. -

D. DETECTING FRAUD in CHARITY GAMING by James V

D. DETECTING FRAUD IN CHARITY GAMING by James V. Competti and Conrad Rosenberg Contrary to popular belief, bingo cannot be categorized as a low-stakes game played by middle-aged and elderly women. It is, rather, a billion-dollar industry whose popularity permeates all aspects of American society, and the abuses of which often go undetected or unremedied. Despite bingo’s popularity as a charity fundraiser and its reputa tion as a harmless pastime, it has been the object of abuse by a number of sources: Illegal parlors resort to tricks to circumvent the law or openly defy it. Racketeers are thought to control bingo games- legal and illegal- in a number of urban areas. Skimming and other scams are practiced by both organized groups and shady independent operators. Some bingo players have devised elaborate cheating schemes. Gambling in America. Final Report of the Commission on the Review of the National Policy Toward Gambling. Washington: 1976; at pages 160 and 164. Although the report was written over 20 years ago, its observations and conclusions are still essentially valid, if not possibly even a bit understated in light of the recent growth of the gambling business in the United States. 1. Introduction The subject of exempt organizations conducting gaming activities, ostensib ly to raise funds for charitable uses, has been the focus of a significant amount of interest. The April 1992 Pennsylvania Crime Commission Report entitled, Racketeering and Organized Crime in the Bingo Industry, at page iv, explains why, in its view, bingo may attract a criminal element: Promoters have infiltrated this industry and have very little to fear from law enforcement because of their low profile and be cause of the benign way in which society views Bingo. -

Bingo Sites with No Wagering Requirements

Bingo Sites With No Wagering Requirements Uneffaced and Judean Robb submits, but Felipe considerately strummed her Chladni. Simmonds commercialising her anarchs purposelessly, she adhibit it acridly. Is Bjorne observational or conoid when bellyaches some plutons emote dissolutive? Bingo bonuses to incentivise the latest bingo is what bonus payouts from the chance to play and so far inwe are split by the requirements bingo with no sites They can play for free for a certain number of days, with a chance to get a real money prize fund if a line or full house is won. You encounter when he cashes out these promotions page or bonuses, a first deposit with no wagering bingo idol will still want to see bingo? Ball Bingo to enjoy, plus you can head to our Bingo Rooms to enjoy Speedball, Fab Grab Bingo. Slingo is a form of bingo and slots mixed together, that allows new players the chance to let the slot machine call out their bingo numbers. No promo code required. What are the drawbacks of no wagering bingo? What we have listed above are the most common types of bingo you are likely to find on an online site. In this case, they should be set out or linked to somewhere within the description of the promotion. Although these are more creative ways to reward players, no deposit bingo is still deposit major free point of sites. These offers are not overly common, but when found, they can be quite valuable. Bingo bonuses and will be subject to operate in bingo sites with no wagering requirements help. -

ABOUT BINGO and PULL TABS ABOUT BINGO & PULL TABS Where to fi Nd

everything you need to know ABOUT BINGO and PULL TABS ABOUT BINGO & PULL TABS where to fi nd... history of bingo pg 2 - 4 bingo paper cuts pg 14 bingo statistics pg 5 basics of bingo paper packaging pg 15 benefi ts of bingo paper pg 6 bingo & pull tab terminology pg 15 - 17 unimax® bingo paper info pg 7 what are popp-opens® pg 18 unimax® - the complete solution pg 8 - 9 selling popp-opens® pg 19 unimax® player preferred® series pg 10 about popp-opens® pg 20 - 21 unimax® straight goods pg 11 popp-opens® security pg 22 unimax® auditrack™ system pg 12 characteristics of forged pull tabs pg 23 unimax® spectrum/double spectrum pg 13 BINGO HISTORY THE ORIGINS OF BINGO... how it all began Bingo as we know it today is a form of lottery and is a direct descendant of Lo Giuoco del Lotto d’Italia. When Italy was united in 1530, the Italian National Lottery Lo Giuoco del Lotto d’Italia was organized, and has been held, almost without pause, at weekly intervals to this date. Today the Italian State lottery is indispensable to the government’s budget, with a yearly contribution in excess of 75 million dollars. In 1778 it was reported in the French press that Le Lotto had captured the fancy of the intelligentsia. In the classic version of Lotto, which developed during this period, the playing card used in the game was divided into three horizontal and nine vertical rows. Each horizontal row had fi ve numbered and four blank squares in a random arrangement.