Toxin-Antitoxin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

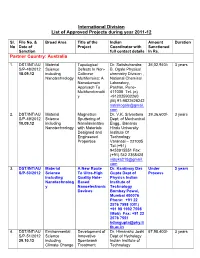

International Division List of Approved Projects During Year 2011-12

International Division List of Approved Projects during year 2011-12 Sl. File No. & Broad Area Title of the Indian Amount Duration No Date of Project Coordinator with Sanctioned Sanction full contact details In Rs. Partner Country: Australia 1. DST/INT/A U Material Topological Dr. Satishchandra 36,02,940/- 3 years S/P-48/2012 Science Defects In Non- B. Ogale Physical 18.09.12 including Collinear chemistry Division , Nanotechnology Multiferroics: A National Chemical Nanodomain Laboratory, Approach To Pashan, Pune- Multifunctionalit 411008 Tel. (o) y +912025902260 (M) 91-9822628242 satishogale@gmail. com 2. DST/INT/AU Material Magnetron Dr. V.K. Srivastava 39,36,600/- 3 years S/P-49/2012 Science Sputtering of Dept. of Mechanical 10.09.12 including Nanolaminates Engg., Banaras Nanotechnology with Materials Hindu University Designed and Institute Of Engineered Technology Properties Varanasi – 221005 Tel.(+91) 9453915551 Fax: (+91) 542 2368428 vijayks210@gmail. com 3. DST/INT/AU Material A New Route Dr. Kantimay Das Under 3 years S/P-50/2012 Science To Ultra-High Gupta Dept of Process including Quality Hole- Physics Indian Nanotechnolog Based Institute of y Nanoelectronic Technology Devices Bombay Powai, Mumbai 400076 Phone: +91 22 2576 7598 (Off.) +91 98 1992 7598 (Mob) Fax: +91 22 2576 7551 [email protected] tb.ac.in 4. DST/INT/AU Environmental Development of Dr. Himanshu Joshi 67,98,400/- 3 years S/P-51/2012 Science Innovative Dept of Hydrology 29.10.12 including Spentwash Indian Institute of Climate Change Treatment Technology Research Systems and Roorkee– 247667, Resource Uttarakhand Recovery himanshujoshi58@ Options for gmail.com; Distillery himanshu_joshi58 Application @yahoo.co.in; [email protected] n 5. -

Strategies for Cryo-Electron Tomography of the Mycobacterial Cell Envelope and Its Pore Proteins and Functional Studies of Porin Mspa from Mycobacterium Smegmatis

Technische Universität München Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie Abteilung für Molekulare Strukturbiologie Strategies for cryo-electron tomography of the mycobacterial cell envelope and its pore proteins and functional studies of porin MspA from Mycobacterium smegmatis Christian Werner Hoffmann Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Chemie der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ. – Prof. Dr. J. Buchner Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Hon. – Prof. Dr. W. Baumeister 2. Univ. – Prof. Dr. S. Weinkauf 3. Univ. – Prof. Dr. W. Liebl Die Dissertation wurde am 28.04.2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Chemie am 14.07.2010 angenommen. TABLE OF CONTENTS A Table of contents A Table of contents .................................................................................................................... I B Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ V C Zusammenfassung............................................................................................................ VIII D Summary ................................................................................................................................ X 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The genus Mycobacterium ............................................................................................. -

2016 03 28 B M.Pdf

file:///C:/Users/Neeraj/Desktop/html/2016_03_28_b_m.htm N O T E ----------------------- ALL ORDINARY MOTION CASES HAVING ADJOURNMENT DATES FROM 23.03.2016 TO 27.03.2016 HAS BEEN SHIFTED TO 28.03.2016 AND FOR THE SAME KINDLY SEE ORDINARY MOTION LIST OF 28.03.2016. ALL CONCERNED TO PLEASE NOTE. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ NOTICE ----------------------- It is for the information of all the Advocates/Litigants that as per the decision of Hon'ble Committee, persons belonging to Schedule Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Backward Class (other than Creamy layer), land less labourer, persons holding yellow card, should file a proof along with the affidavit stating therein that he/she belongs to marginalized section of Society. The cases relating to "Crime Against Children, differently abled persons, senior citizens and marginalized sections of Society" will be given priority. The Members of the Bar are requested to provide the information regarding the cases relating to the aforesaid categories which have already been filed by them so that data in the computer can be updated for monitoring of these cases. Sd/- Joint Registrar (Judicial-II) 21.03.2016 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NOTICE ---------------------- Learned members of the Bar are requested to give the list of cases which have to be transferred to the Educational Tribunal, Punjab, in terms of the Jurisdiction conferred under section 7-a(12) of the Punjab affiliated colleges (security of service of employees) Act, 1974, as amended upto late and the Punjab Privately Managed Recognised Schools Employees (security) Act, 1979, in the Registry so that these cases should be listed for hearing. sd/ Registrar Judicial 1 URGENT D.B. -

Expression and Regulation of the Porin Gene Mspa of Mycobacterium Smegmatis

Expression and regulation of the porin gene mspA of Mycobacterium smegmatis Den Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades vorgelegt von Dietmar Hillmann aus Nürnberg Als Dissertation genehmigt von den Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultäten der Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 15.12.2006 Vorsitzender der Promotionskommission: Prof. Dr. E. Bänsch Erstberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. M. Niederweis Zweitberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. A. Burkovski Index Index 1 Zusammenfassung / Summary 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 The genus Mycobacterium 2 2.1.1 Taxonomy 2 2.1.2 The architecture of the mycobacterial cell wall 3 2.2 Porins: Structure and function in gram-negative bacteria 5 2.3 Mycobacterial porins 7 2.4 Porin regulation 10 2.5 Expression of mspA of M. smegmatis 12 2.6 Scope of the thesis 13 3 Results 14 3.1 Screening system to monitor mycobacterial promoter activity 14 3.2 Transcriptional mechanisms affecting mspA expression 18 3.2.1 Identification of the mspA promoter 18 3.2.2 A very long upstream DNA element is required for full activity of pmspA 22 3.2.3 Influence of translation initiation signals of pmspA on lacZ expression 24 3.2.4 Influence of a distal DNA element on pmspA activation 25 3.2.5 Alignment of the 5’ regions of mspA, mspB, mspC and mspD 27 3.3 Post-transcriptional mechanisms affecting mspA expression 28 3.3.1 Detection of an antisense RNA to the mspA transcript 28 3.3.2 Secondary structure of the 5’ UTR of mspA 31 3.4 pH dependent mspA expression -

Romanian Journal of Military Medicine

Founded 1897 • New Series Romanian Journal of Vol. CXXII • No. 3/2019 • December Military Medicine REVISTA DE MEDICINĂ MILITARĂ • About malpraxis, with love • Current therapeutic strategies for erectile function recovery after radical prostatectomy – literature review and meta-analysis • Toxoplasma Gondii infection and the signs of fetal affection during pregnancy as seen on ultrasound • High values of procalcitonin in non-septic patients with thermal and airway burns • Management of war-related vascular injuries. A civilian surgeon experience in the treatment of war casualties at a secondary care hospital • 3D echo in everyday life: Could it reset our threshold for interventions? • Aptamer as a proper alternative instead of monoclonal antibody in diagnosis and neutralization of menacing biological agents • Alteration of levels of thyroid hormones in acute ischemic stroke and its correlation with severity and functional outcome • Characteristics and complications of supernumerary permanent teeth in a sample of patients examined in a university pedodontics clinic • Development of quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay for detection and viral load determination of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) virus • Prioritisation In delivering health services – a military health system example • Why cancer/terminal ill diagnosis unsuccessful in India: a qualitative analysis • Simulation and dynamic analysis of military marching using lower limbs anthropometric data • Drug allergies interpretation based on patient’s history alone may have therapeutic -

Structure of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Ompatb Protein: a Model of an Oligomeric Channel in the Mycobacterial Cell Wall

proteins STRUCTURE O FUNCTION O BIOINFORMATICS Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis OmpATb protein: A model of an oligomeric channel in the mycobacterial cell wall Yinshan Yang,1,2 Daniel Auguin,1,2,3 Ste´phane Delbecq,4 Emilie Dumas,1,2 Ge´rard Molle,1,2 Virginie Molle,5 Christian Roumestand,1,2* and Nathalie Saint1,2 1 Centre de Biochimie Structurale, CNRS UMR 5048, Universite´ Montpellier 1 et 2, F34090 Montpellier, France 2 INSERM U554 F34090 Montpellier, France 3 INRA, USC2030 ‘Arbres et Re´ponses aux Contraintes Hydrique et Environnementales’ (ARCHE), F-45067 Orle´ans Cedex 02, France 4 Dynamique des Interactions Membranaires Normales et Pathologiques, CNRS UMR 5235, Universite´ Montpellier 2, F34095 Montpellier Cedex 5, France 5 Institut de Biologie et de Chimie des Prote´ines, Universite´ de Lyon, CNRS UMR 5086, F69367 Lyon, France ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The pore-forming outer membrane protein The etiological agent of tuberculosis (TB), Mycobacterium OmpATb from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a viru- tuberculosis, causing nearly 2 million deaths per year, is presently lence factor required for acid resistance in host one of the most important infectious agents implicated in mortal- phagosomes. In this study, we determined the 3D ity worldwide. TB has emerged as a major public health threat structure of OmpATb by NMR in solution. We because of a significant increase in multiple-drug-resistant TB and found that OmpATb is composed of two independ- synergism between human immunodeficiency virus and M. tuber- ent domains separated by a proline-rich hinge culosis infection.1,2 One of the principle problems in TB therapy region. -

2017 05 31 O M.Pdf

file:///C:/Users/Niraj/Desktop/html/2017_05_31_o_m.htm N O T I C E ---------------------------- Advocates are requested to supply list of the cases which are covered by judgement of five Judges of this Hon'ble High Court in CWP No. 314 of 2001 titled as Suraj Bhan and others Vs State of Haryana and another decided on 22.07.2016 to the Registrar, (Judicial). ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- N O T E ------------------------- It is informed to the Advocates/Parties that 29.05.2017 (Monday) has been declared as holiday in this Hon’ble High Court on account of Martyrdom Day of Sri Guru Arjan Dev Ji instead of 16.06.2017 (Friday) and the Saturday falling on 16.12.2017 will be observed as Court Working day in lieu of holiday declared on 29.05.2017 in this Hon’ble High Court. Cases which are pending for 29.05.2017 will be taken up on 30.05.2017. Similarly, 23.11.2017 (Thursday) has been declared as holiday in this Hon’ble High Court on account of Martyrdom Day of Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Ji instead of 24.11.2017 (Friday) and 24.11.2017 already declared holiday will now be observed as working day in this Hon’ble High Court. Cases which are pending for 23.11.2017 will be taken up on 24.11.2017. B.O. of Hon’ble the Chief Justice sd/- Jt. Registrar (J-II) 18.05.2017 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- N O T I C E -------------------------------- It is for the kind notice of the Advocates/parties that Review Applications should be filed complete in all respects and in case of delay, the same will be listed before the appropriate Hon'ble Benches by recording an office note of such defects. -

Centenary Celebration of Bose Institute

C E N T E N A R Y C E L E B R AT I O N CCEENNTTEENNAARRYY CCEELLEEBBRRAATTIIOONN OOFF BBOOSSEE IINNSSTTIITTUUTTEE 1 9 1 7 - 2 0 1 7 List of Posters (24.11.2017–28.11.2017) Poster Faculty Programme Title Poster Faculty Programme Title No No A-1 Amita Pal I Molecular characterization of VmMAPK1 and deciphering its role in restricting D-10 Tanya Das IV Is cancer a stem cell disease? MYMIV multiplication in tobacco Poulami Khan, Apoorva Bhattacharya, Shruti Banerjee, Swastika Paul, Abhishek Dutta, Anju Patel, Pankaj Kumar Singh, Shubho Chaudhuri and Amita Pal Dipanwita Dutta Chowdhury, Udit Basak, Apratim Dutta, Arijit Bhowmik, Devdutt A-2 Anupama Ghosh I Induction of apoptosis-like cell death and clearance of stress-induced intracellular Mazumdar, Aparajita Das, Sourio Chakraborty and Tanya Das protein aggregates: dual roles for Ustilago maydis metacaspase Mca1. E-1 Abhrajyoti Ghosh V Deciphering the code behind prokaryotic stress responses and ecophysiology A-1 Dibya Mukherjee, Sayandeep Gupta, Saran N, Rahul Datta, Anupama Ghosh Mousam Roy, Sayandeep Gupta, Chandrima Bhattacharyya, Shayantan Mukherji, A-3 Debabrata Basu I A multifaceted approach to unravel the signalling components of 'Black Spot' Abhrajyoti Ghosh A-2 disease resistance in oilseed mustard E-2 Srimonti Sarkar V The minimal ESCRT machinery of Giardia lamblia has altered inter-subunit Mrinmoy Mazumder, Amrita Mukherjee, Banani Mondal, Swagata Ghosh, Aishee De interactions within the ESCRT-II and ESCRT-III complexes A-3 and Debabrata Basu Nabanita Saha, Somnath Dutta and Srimonti Sarkar A-4 I Gaurab Gangyopadhyay Towards broadening the gene pool of few crop plants through molecular and E-3 Subrata Sau V Identification, purification and characterization of a cyclophilin from A-4 transgenic breeding Staphylococcus aureus Debabrata Dutta, Soumili Pal, Marufa Sultana, Vivek Arora and Gaurab Soham Seal, Debabrata Sinha, Subrata Sau Gangopadhyay E-4 Sujoy Kr. -

PE PGRS33 Contributes to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Entry in Macrophages Through Interaction with TLR2

RESEARCH ARTICLE PE_PGRS33 Contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Entry in Macrophages through Interaction with TLR2 Ivana Palucci1, Serena Camassa1, Alessandro Cascioferro3, Michela Sali1, Saber Anoosheh3, Antonella Zumbo1, Mariachiara Minerva1, Raffaella Iantomasi1, Flavio De Maio1, Gabriele Di Sante2, Francesco Ria2, Maurizio Sanguinetti1, Giorgio Palù3, Michael J. Brennan4, Riccardo Manganelli3, Giovanni Delogu1* 1 Institute of Microbiology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go A. Gemelli, 8–00168, Rome, Italy, 2 Institute of General Pathology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go A. Gemelli, 8–00168, Rome, Italy, 3 Department of Molecular Medicine, University of Padua, Via A. Gabelli, 63–35121, Padua, Italy, 4 Aeras, Rockville (MD), United States of America * [email protected] Abstract PE_PGRS represent a large family of proteins typical of pathogenic mycobacteria whose members are characterized by an N-terminal PE domain followed by a large Gly-Ala repeat- OPEN ACCESS rich C-terminal domain. Despite the abundance of PE_PGRS-coding genes in the Myco- Citation: Palucci I, Camassa S, Cascioferro A, Sali bacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) genome their role and function in the biology and pathogene- M, Anoosheh S, Zumbo A, et al. (2016) PE_PGRS33 sis still remains elusive. In this study, we generated and characterized an Mtb H37Rv Contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Entry in mutant (MtbΔ33) in which the structural gene of PE_PGRS33, a prototypical member of the Macrophages through Interaction with TLR2. PLoS ONE 11(3): e0150800. doi:10.1371/journal. protein family, was inactivated. We showed that this mutant entered macrophages with an pone.0150800 efficiency up to ten times lower than parental or complemented strains, while its efficiency in Editor: Joyoti Basu, Bose Institute, INDIA infecting pneumocytes remained unaffected. -

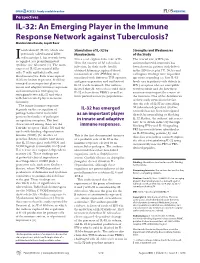

IL-32: an Emerging Player in the Immune Response Network Against Tuberculosis? Manikuntala Kundu, Joyoti Basu*

Perspectives IL-32: An Emerging Player in the Immune Response Network against Tuberculosis? Manikuntala Kundu, Joyoti Basu* nterleukin-32 (IL-32), which was Stimulation of IL-32 by Strengths and Weaknesses previously called natural killer Mycobacteria of the Study cell transcript 4, has recently been I Netea et al. explored the role of IL- The crucial role of IFN-γ in recognized as a proinfl ammatory 32 in the context of M. tuberculosis antimycobacterial immunity has cytokine (see Glossary) [1]. The main infection. In their study, freshly been shown in patients with defects sources of IL-32 are natural killer obtained human peripheral blood in the IFN-γ receptor [7]. Netea and cells, T cells, epithelial cells, and mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were colleagues’ fi ndings raise important blood monocytes. Four transcripts of stimulated with different TLR agonists, questions regarding (a) how IL-32 IL-32 are known at present. IL-32 has and gene expression and synthesis of levels vary in patients with defects in emerged as an important player in IL-32 was determined. The authors IFN-γ receptors who are susceptible innate and adaptive immune responses, showed that M. tuberculosis could elicit to tuberculosis and (b) how these and information is emerging on IL-32 release from PBMCs as well as variations may impact the course of synergism between IL-32 and other from purifed monocyte populations. the infection. One of the defi ciencies well-characterized players in innate of their study stems from the fact immunity. that the role of IL-32 in controlling The innate immune response M. -

O509 2-Hour Oral Session Frontiers in Tuberculosis the Role of Micrornas

O509 2-hour Oral Session Frontiers in tuberculosis The role of microRNAs in tuning the immune response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection Joyoti Basu*1 1Bose Institute, Chemistry, Kolkata, India Background: The role of post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in calibrating the immune response of macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains poorly understood. We have performed global miRNA and transcriptome profiling to build an miRNA – mRNA network in Mtb- infected macrophages, and to understand its impact on the immune response to infection. Material/methods: We have performed global qRT-PCR profiling of miRNAs and microarray analysis of mRNAs to profile the transcriptome of macrophages infected with Mtb. Bioinformatic analyses has been performed using the tool MAGIA, to build an miRNA-mRNA network. We have then focused on selected miRNAs to analyze their effects on the immune response by analyzing pathways associated with inflammation and autophagy. Results: During Mtb infection, the let-7 miRNAs appeared as highly connected nodes of the miRNA- mRNA network. We establish that A 20 (TNFAIP3), a negative regulator of NF- B signaling is a target of let- 7. Augmented release of TNF-alfa, IL-1beta, CCL2, CXCL1, IL-6 and NO occurs in Mtb- infected macrophages in the absence of A20. During infection, downregulation of let -7f leads to concomitant rise in A20, likely tuning down inflammatory mediators. Transfection with a let -7f mimic, leads to increased cytokine release after infection. In addition to let-7f, miR-17 family members are also downregulated during Mtb infection of macrophages. We show that forced expression of miR-17 enhances autophagy during Mtb infection. -

![ORDERS (INCOMPLETE MATTERS / Ias / Crlmps)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8138/orders-incomplete-matters-ias-crlmps-1108138.webp)

ORDERS (INCOMPLETE MATTERS / Ias / Crlmps)]

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA [ IT WILL BE APPRECIATED IF THE LEARNED ADVOCATES ON RECORD DO NOT SEEK ADJOURNMENT IN THE MATTERS LISTED BEFORE ALL THE COURTS IN THE CAUSE LIST ] DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 06-01-2020 CHIEF JUSTICE'S COURT HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE B.R. GAVAI HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SURYA KANT (TIME : 10:30 AM) NOTE :- Request for "Not to delete a matter" and all Circulations (If the matters are not on Board for the day) need not be mentioned before the Bench. Such request be handed over to the concerned Court Masters in advance before 10.30 A.M. MISCELLANEOUS HEARING Petitioner/Respondent SNo. Case No. Petitioner / Respondent Advocate EARLY HEARING APPLICATION IN ADMITTED MATTERS 1 C.A. No. KAMLESHWAR RAJBONGSHI (DEAD) THROUGH LRS. AVIJIT BHATTACHARJEE[P-1] 3541-3542/2018 XIV-A Versus GUNESWAR RAJBONGSHI . AND ANR. AVIJIT ROY[R-1] {Mention Memo} I.A.NO. 123329/2019 (APPLN. FOR RESTORATION OF EARLY HEARING) TO BE LISTED. IA No. 123329/2019 - RESTORATION [ORDERS (INCOMPLETE MATTERS / IAs / CRLMPs)] 2 W.P.(C) No. 274/2009 ASSAM PUBLIC WORKS KAILASH PRASHAD PIL-W PANDEY[P-1] Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. GAURAV DHINGRA[IMPL], B. KRISHNA PRASAD[IMPL], SNEHASISH MUKHERJEE[R-1], SHUVODEEP ROY[R-1], SHIBASHISH MISRA[R-1], SHADAN FARASAT[R-1], MOHIT D. a RAM[R-1], MOHAN PANDEY[R-1], MADHUMITA BHATTACHARJEE[R-1][IMPL] , GUNTUR PRABHAKAR[R-1], FUZAIL AHMAD AYYUBI[R-1], [INT], [IMPL], B. V. BALARAM a DAS[R-1], ABHIJIT SENGUPTA[R-1] SNEHA KALITA[IMPL], SANAND RAMAKRISHNAN[IMPL], MOHIT CHAUDHARY[IMPL], AVIJIT ROY[IMPL], CORPORATE LAW DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 06-01-2020 CHIEF JUSTICE'S COURT a GROUP[IMPL] T.