Older Suburbs in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

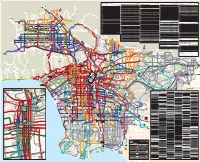

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

Millard Sheets Was Raised and Became Sensitive to California’S Agricultural Lifestyle

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY I A A R R N T O F C I L L U A B C CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER Documenting California’s Traditional Arts Heritage for More Than 100 Years e s 9 t a 9 0 b lis h e d 1 attracted 49,000 visitors. It was in this rural environment that Millard Sheets was raised and became sensitive to California’s agricultural lifestyle. Millard Sheets’ mother died in childbirth. His father, John Sheets, was deeply distraught and unable to raise his son on his own. Millard was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, Louis and Emma Owen, on their neighbouring horse ranch. His grandmother, at age thirty-nine, and grandfather, at age forty, were still relatively young. Additionally, with two of their four youngest daughters, ages ten and fourteen, living at home, family life appeared normal. His grandfather, whom Millard would call “father,” was an accomplished horseman and would bring horses from Illinois to race against Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin (1828-1909) at Baldwin’s “Santa Anita Stable,” later to become Santa Anita Park. The older of Millard’s two aunts babysat him and kept him occupied Abandoned, 1934 with doing drawings. Oil on canvas 39 5/80 3 490 Collection of E. Gene Crain he magic of making T pictures became a fascination to Sheets, as he would later explain in Millard Sheets: an October 28, 1986 interview conducted A California Visionary by Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian by Gordon T. McClelland and Elaine Adams Institution: “When I was about ten, I found out erhaps more than any miles east of downtown Los Angeles. -

Los Angeles from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "L.A." and "LA" Redirect Here

Los Angeles From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "L.A." and "LA" redirect here. For other uses, see L.A. (disambiguation). This article is about the U.S. city. For the county, see Los Angeles County, California. For other uses, see Los Angeles (disambiguation). Los Angeles City City of Los Angeles From top: Downtown Los Angeles, Venice Beach, Griffith Observatory, Hollywood Sign Flag Seal Nickname(s): "L.A.", "City of Angels",[1]"Angeltown",[2] "Lalaland", "Tinseltown"[3] Location in Los Angeles County in the state of California Los Angeles Location in the United States Coordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′WCoordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′W Country United States of America State California County Los Angeles Settled September 4, 1781 Incorporated April 4, 1850 Government • Type Mayor-Council • Body Los Angeles City Council • Mayor Eric Garcetti (D) • City Mike Feuer Attorney • City Ron Galperin Controller Area[4] • City 503 sq mi (1,302 km2) • Land 469 sq mi (1,214 km2) • Water 34 sq mi (88 km2) 6.7% Elevation 233 (city hall) ft (71 m) Population (2012) • City 3,857,799 • Rank 2nd U.S., 48th world • Density 8,225/sq mi (3,176/km2) • Urban 15,067,000[6] • Metro 16,400,000[5] • CSA 17,786,419 Demonym Angeleno Time zone PST (UTC-8) • Summer PDT (UTC−7) (DST) ZIP code 90001–90068, 90070–90084, 90086–90089, 90091, 90093–90097, 90099, 90101–90103, 90174, 90185, 90189, 90291–90293, 91040– 91043, 91303–91308, 91342–91349, 91352– 91353, 91356–91357, 91364–91367, 91401– 91499, 91601–91609 Area code(s) 213, 310/424, 323, 661,747/818 FIPS code 06-44000 GNIS feature 1662328 ID Website lacity.org Los Angeles ( i/lɔːs ˈændʒələs/, /lɔːs ˈæŋɡələs/ or i/lɒs ˈændʒəliːz/, Spanish: Los Ángeles [los ˈaŋxeles] meaning The Angels), officially the City of Los Angeles, often known by its initials L.A., is themost populous city in the U.S. -

A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante

But Why Glendale? But Why Glendale? A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante Abstract: Despite its many contributions to Los Angeles, the internally complex community of Armenian Angelenos remains enigmatically absent from academic print. As a result, its history remains untold. While Armenians live throughout Southern California, the greatest concentration exists in Glendale, where Armenians make up a demographic majority (approximately 40 percent of the population) and have done much to reconfigure this homogenous, sleepy, sundown town of the 1950s into an ethnically diverse and economically booming urban center. This article presents a brief history of Armenian immigration to Southern California and attempts to explain why Glendale has become the world’s most demographically concentrated Armenian diasporic hub. It does so by situating the history of Glendale’s Armenian community in a complex matrix of international, national, and local events. Keywords: California history, Glendale, Armenian diaspora, immigration, U.S. ethnic history Introduction Los Angeles contains the most visible Armenian diaspora worldwide; however yet it has received virtually no scholarly attention. The following pages begin to shed light on this community by providing a prefatory account of Armenians’ historical immigration to and settlement of Southern California. The following begins with a short history of Armenian migration to the United States. The article then hones in on Los Angeles, where the densest concentration of Armenians in the United States resides; within the greater Los Angeles area, Armenians make up an ethnic majority in Glendale. To date, the reasons for Armenians’ sudden and accelerated settlement of Glendale remains unclear. While many Angelenos and Armenian diasporans recognize Glendale as the epicenter of Armenian American habitation, no one has yet clarified why or how this came about. -

Los Angeles Bibliography

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN THE LOS ANGELES METROPOLITAN AREA Compiled by Richard Longstreth 1998, revised 16 May 2018 This listing focuses on historical studies, with an emphasis is on scholarly work published during the past thirty years. I have also included a section on popular pictorial histories due to the wealth of information they afford. To keep the scope manageable, the geographic area covered is primarily limited to Los Angeles and Orange counties, except in cases where a community, such as Santa Barbara; a building, such as the Mission Inn; or an architect, such as Irving Gill, are of transcendent importance to the region. Thanks go to Kenneth Breisch, Dora Crouch, Thomas Hines, Greg Hise, Gail Ostergren, and Martin Schiesl for adding to the list. Additions, corrections, and updates are welcome. Please send them to me at [email protected]. G E N E R A L H I S T O R I E S A N D U R B A N I S M Abu-Lughod, Janet, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's Global Cities, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999 Adler, Sy, "The Transformation of the Pacific Electric Railway: Bradford Snell, Roger Rabbit, and the Politics of Transportation in Los Angeles," Urban Affairs Quarterly 27 (September 1991): 51-86 Akimoto, Fukuo, “Charles H. Cheney of California,” Planning Perspectives 18 (July 2003): 253-75 Allen, James P., and Eugene Turner, The Ethnic Quilt: Population Diversity in Southern California Northridge: Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 1997 Avila, Eric, “The Folklore of the Freeway: Space, Culture, and Identity in Postwar Los Angeles,” Aztlan 23 (spring 1998): 15-31 _________, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles, Berkeley: University of California Pres, 2004 Axelrod, Jeremiah B. -

Historical Resources Assessment

C‐3 ‐ Historical Resources Assessment HISTORICAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT REPORT AND IMPACTS ANALYSIS FOR THE PROPOSED 8150 SUNSET BOULEVARD MIXED USE PROJECT 8150 W. SUNSET BOULEVARD LOS ANGELES, LOS ANGELES COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for AG-SCH 8150 Sunset Boulevard Owner, L.P. 8899 Beverly Blvd., Suite 710 West Hollywood, California 90048 Prepared by Margarita J. Wuellner, Ph.D. And Amanda Y. Kainer, M.S. PCR Services Corporation 201 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 500 Santa Monica, CA 90401 September 2014 Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 B. Project Site ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 C. Project Description ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 D. Research and Field Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 7 II. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................................................................ -

Contractor List

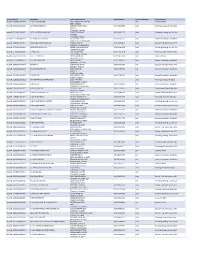

Active Licenses DBA Name Full Primary Address Work Phone # Licensee Category SIC Description buslicBL‐3205002/ 28/2020 1 ON 1 TECHNOLOGY 417 S ASSOCIATED RD #185 cntr Electrical Work BREA CA 92821 buslicBL‐1684702/ 28/2020 1ST CHOICE ROOFING 1645 SEPULVEDA BLVD (310) 251‐8662 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met UNIT 11 TORRANCE CA 90501 buslicBL‐3214602/ 28/2021 1ST CLASS MECHANICAL INC 5505 STEVENS WAY (619) 560‐1773 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con #741996 SAN DIEGO CA 92114 buslicBL‐1617902/ 28/2021 2‐H CONSTRUCTION, INC 2651 WALNUT AVE (562) 424‐5567 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia SIGNAL HILL CA 90755‐1830 buslicBL‐3086102/ 28/2021 200 PSI FIRE PROTECTION CO 15901 S MAIN ST (213) 763‐0612 subc Special Trade Contractors, NEC GARDENA CA 90248‐2550 buslicBL‐0778402/ 28/2021 20TH CENTURY AIR, INC. 6695 E CANYON HILLS RD (714) 514‐9426 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con ANAHEIM CA 92807 buslicBL‐2778302/ 28/2020 3 A ROOFING 762 HUDSON AVE (714) 785‐7378 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met COSTA MESA CA 92626 buslicBL‐2864402/ 28/2018 3 N 1 ELECTRIC INC 2051 S BAKER AVE (909) 287‐9468 cntr Electrical Work ONTARIO CA 91761 buslicBL‐3137402/ 28/2021 365 CONSTRUCTION 84 MERIDIAN ST (626) 599‐2002 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia IRWINDALE CA 91010 buslicBL‐3096502/ 28/2019 3M POOLS 1094 DOUGLASS DR (909) 630‐4300 cntr Special Trade Contractors, NEC POMONA CA 91768 buslicBL‐3104202/ 28/2019 5M CONTRACTING INC 2691 DOW AVE (714) 730‐6760 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia UNIT C‐2 TUSTIN CA 92780 buslicBL‐2201302/ 28/2020 7 STAR TECH 2047 LOMITA BLVD (310) 528‐8191 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia LOMITA CA 90717 buslicBL‐3156502/ 28/2019 777 PAINTING & CONSTRUCTION 1027 4TH AVE subc Painting and Paper Hanging LOS ANGELES CA 90019 buslicBL‐1920202/ 28/2020 A & A DOOR 10519 MEADOW RD (213) 703‐8240 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia NORWALK CA 90650‐8010 buslicBL‐2285002/ 28/2021 A & A HENINS, INC. -

Master Inventory of Millard Sheets Studio and Home Savings Art and Architecture-Published Version August 2018.Xlsx

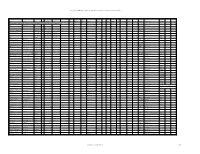

Master Inventory of Millard Sheets Studio and Home Savings Art and Architecture-Published Version August 2018.xlsx Branch Name Owner Date Acquired Art Construction Branch (if different before Date Last Stained Fabric Painted Archival Firm Address City State or Opened Date Location Closed Number than city) Home Status Seen Mosaic? Glass? Sculpture? work? Furnishings? mural? No Art? Subject(s) Worked On By Records Copyright 2018 by Adam Arenson - please use to support documentation and preservation efforts, crediting the source. South Pasadena Junior High frescoes - School 1500 Fair Oaks Avenue South Pasadena CA 1929 1929 destroyed by 1935 Y California Millard Sheets (Unknown Name) beach club Long Beach CA before 1932 1930 Millard Sheets, Phil Dike (date and Scripps College Art Building Claremont CA 1930 specifics before 1932, before 1932, likely destroyed before Sheets Robinson’s Company Los Angeles CA likely 1929-1932 1929-1932 1975 Y Y Fantasie Millard Sheets exhibit State Mutual Building and before 1932, before 1932, likely AAA- Loan Los Angeles CA likely 1929-1932 1929-1932 Y Millard Sheets Millard before 1932, before 1932, likely Sheets YMCA Pasadena CA likely 1929-1932 1929-1932 Y exhibit covered then Modern Bullock’s Men’s Store 640 S Hill St Los Angeles CA 1934 1934 uncovered in 1975; Y World Millard Sheets mural in Beverly Hills Hotel 9641 Sunset Blvd Beverly Hills CA 1935 main lobby: Millard Sheets (date and Beverly Hills Tennis Club 340 North Maple Drive Beverly Hills CA 1935 not there, if ever 2014 Y specifics Millard Sheets -

Metro Bus & Metro Rail System

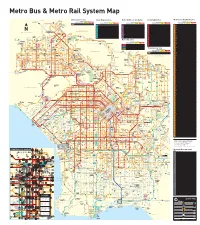

Metro Bus & Metro Rail System Map Metro Local & Limited Lines to Santa Clarita LA County Metro Liner Service Metro Express Lines Metro Shuttles & Circulators Metro Rapid Lines to Santa Clarita Olive View-UCLA Approximate frequency in minutes and Antelope Valley Medical Center Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes '&% H>BH=6L Weekdays Saturdays Sundays * 236 Line Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Weekdays Saturdays Sundays CE409 224 234 Line Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve SC8 7A:9HD:290 634 Orange 4-5 10 10-20 11-12 10-20 11-12 10-20 Line Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve El Cariso 2 4-10 9-12 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Regional 439 30-45 40-60 60b 60b 60 60 60b 603 10-12 12 30 20-30 20-30 20 30 704 8-12 15 18b 12-18 18b 15-25 18b 4 8-15 15-16 15-30 13-20 15-30 15-30 15-30 County Park 442 25 - - - - - - 605 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a 705 10-20 20 20 - - - - 234 H6NG: 10 7-15 15-30 15-30 12-20 30-60 15-30 30-60 236 7DG9:C GDM;DG9 LA Mission 444 10-30 60 60a 60 60a 60 60a 607 35 - - - - - - 710 8-10 20 20a 20 20a - - SC8 <A:CD6@H 14 12-25 20 20-60 15-20 20-60 15-30 20-60 H6C;:GC6C9DG9224 College 445 30 60 30-60 60 60a 60 60a 608 60 60 - - - - - 711 9-10 20 12-20 15-20 25 20 25 =J776G9 16 2-6 7-8 10-30 6-10 10-30 8-20 12-30 290 446 25-40 60c 60 60c 60 60c 60 611 11-35 40 30-50 30-40 30-50 30-40 30-50 714 -

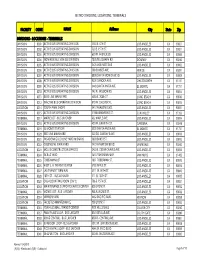

Master List of Mta Divisions Locations Stations 073009

METRO DIVISIONS, LOCATIONS, TERMINALS FACILITY CODE NAME Address City State Zip DIVISIONS - LOCATIONS - TERMINALS DIVISION 0001 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 1130 E. 6TH ST LOS ANGELES CA 90021 DIVISION 0002 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 720 E. 15TH ST. LOS ANGELES CA 90021 DIVISION 0003 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 630 W. AVENUE 28 LOS ANGELES CA 90065 DIVISION 0004 NON-REVENUE VEHICLE DIVISION 7878 TELEGRAPH RD. DOWNEY CA 90240 DIVISION 0005 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 5425 VAN NESS AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90062 DIVISION 0006 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 100 SUNSET AVE. VENICE CA 90291 DIVISION 0007 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 8800 SANTA MONICA BLVD. LOS ANGELES CA 90069 DIVISION 0008 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 9201 CANOGA AVE. CHATSWORTH CA 91311 DIVISION 0009 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 3449 SANTA ANITA AVE. EL MONTE CA 91731 DIVISION 0010 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 742 N. MISSION RD. LOS ANGELES CA 90033 DIVISION 0011 BLUE LINE MAIN YARD 4350 E. 208th ST. LONG BEACH CA 90810 DIVISION 0012 INACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 970 W. CHESTER PL. LONG BEACH CA 90813 LOCATION 0014 SOUTH PARK SHOPS 5413 AVALON BLVD. LOS ANGELES CA 90011 DIVISION 0015 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 11900 BRANFORD ST. SUN VALLEY CA 91352 TERMINAL 0017 MAPLE LOT - BUS LAYOVER 632 MAPLE AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90014 DIVISION 0018 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 450 W. GRIFFITH ST. GARDENA CA 90248 TERMINAL 0019 EL MONTE STATION 3501 SANTA ANITA AVE. EL MONTE CA 91731 DIVISION 0020 RED LINE MAIN YARD 320 SO. SANTA FE AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90013 DIVISION 0021 PASADENA GOLD LINE YARD(MIDWAY) 1800 BAKER ST. -

Download (Pdf)

1. M FOR PUBLICATION BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM LJioS THIS COMPILATION IS DERIVED LARGELY FROM SECONDARY SOURCE^eptember 2k, 1962 NOT AN OFFICIAL REPORT OF CHANGES IN THE BANKING STRUCTURE. CHANGES IN STATUS OF BANKS AND BRANCHES CURING AUGUST 1962 LIBRARY J "Class Bate of Name pnd location of banks and branches of bank change MAR 7 !%J ' ! New Banks (Except succassions and conversions) Planters & Stockmen Bank Pocahontas, Ark. Ins.non. 8-10-62 Randolph County- Vilshire National Bank Los Angeles, Calif0 National 6-1-62 Los Angeles County Peoples Bank of Stuart Stuart, Fla. Ins.non« 6-9-62 Martin County Community Bank of Easton Easton, 111, Ins.none 8-1-62 Mason County First Bank of Meadovrview Kankakee, 111. Ins.non. 6-10-62 Kankakee County Randhurst Bank Mount Prospect, 111. Ins.non, 8-7-62 Cook County Exchange State Bank Lime Springs, Iowa Nonins. 7-2-62 Howard County (Certain of the assets and deposit liabilities of The Exchange State Bank, Lime Springs, Iowa, were purchased and assumed by the new bank organized under the same nar.e„) Parklane National Bank Wichita, Kanso National 6-16-62 Sedgwick County Lincoln Bank & Trust Co. Ruston, La. Ins.non* 8-1-62 Lincoln Parish Town Bank & Trust Co. Brookline, Mass. Ins.non* 8-1-62 Norfolk County Central National Bank Alma, Mich. National 8-29-62 Gratiot County Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis -2- | Class Date of Name and location of banks and branches | of bank change New Banks (Cont'd) (Except successions and conversions) East Texas State Bank Buna, Tex.