In Los Angeles, Art That's Worth the Detour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Pashgianhelen Helen Pashgian L Acm a Delmonico • Prestel

HELEN HELEN PASHGIAN ELIEL HELEN PASHGIAN LACMA DELMONICO • PRESTEL HELEN CAROL S. ELIEL PASHGIAN 9 This exhibition was organized by the Published in conjunction with the exhibition Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Funding at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California is provided by the Director’s Circle, with additional support from Suzanne Deal Booth (March 30–June 29, 2014). and David G. Booth. EXHIBITION ITINERARY Published by the Los Angeles County All rights reserved. No part of this book may Museum of Art be reproduced or transmitted in any form Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard or by any means, electronic or mechanical, March 30–June 29, 2014 Los Angeles, California 90036 including photocopy, recording, or any other (323) 857-6000 information storage and retrieval system, Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville www.lacma.org or otherwise without written permission from September 26, 2014–January 4, 2015 the publishers. Head of Publications: Lisa Gabrielle Mark Editor: Jennifer MacNair Stitt ISBN 978-3-7913-5385-2 Rights and Reproductions: Dawson Weber Creative Director: Lorraine Wild Designer: Xiaoqing Wang FRONT COVER, BACK COVER, Proofreader: Jane Hyun PAGES 3–6, 10, AND 11 Untitled, 2012–13, details and installation view Formed acrylic 1 Color Separator, Printer, and Binder: 12 parts, each approx. 96 17 ⁄2 20 inches PR1MARY COLOR In Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2014 This book is typeset in Locator. PAGE 9 Helen Pashgian at work, Pasadena, 1970 Copyright ¦ 2014 Los Angeles County Museum of Art Printed and bound in Los Angeles, California Published in 2014 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art In association with DelMonico Books • Prestel Prestel, a member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich Germany Tel.: +49 (0)89 41 36 0 Fax: +49 (0)89 41 36 23 35 Prestel Publishing Ltd. -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

Los Angeles from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "L.A." and "LA" Redirect Here

Los Angeles From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "L.A." and "LA" redirect here. For other uses, see L.A. (disambiguation). This article is about the U.S. city. For the county, see Los Angeles County, California. For other uses, see Los Angeles (disambiguation). Los Angeles City City of Los Angeles From top: Downtown Los Angeles, Venice Beach, Griffith Observatory, Hollywood Sign Flag Seal Nickname(s): "L.A.", "City of Angels",[1]"Angeltown",[2] "Lalaland", "Tinseltown"[3] Location in Los Angeles County in the state of California Los Angeles Location in the United States Coordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′WCoordinates: 34°03′N 118°15′W Country United States of America State California County Los Angeles Settled September 4, 1781 Incorporated April 4, 1850 Government • Type Mayor-Council • Body Los Angeles City Council • Mayor Eric Garcetti (D) • City Mike Feuer Attorney • City Ron Galperin Controller Area[4] • City 503 sq mi (1,302 km2) • Land 469 sq mi (1,214 km2) • Water 34 sq mi (88 km2) 6.7% Elevation 233 (city hall) ft (71 m) Population (2012) • City 3,857,799 • Rank 2nd U.S., 48th world • Density 8,225/sq mi (3,176/km2) • Urban 15,067,000[6] • Metro 16,400,000[5] • CSA 17,786,419 Demonym Angeleno Time zone PST (UTC-8) • Summer PDT (UTC−7) (DST) ZIP code 90001–90068, 90070–90084, 90086–90089, 90091, 90093–90097, 90099, 90101–90103, 90174, 90185, 90189, 90291–90293, 91040– 91043, 91303–91308, 91342–91349, 91352– 91353, 91356–91357, 91364–91367, 91401– 91499, 91601–91609 Area code(s) 213, 310/424, 323, 661,747/818 FIPS code 06-44000 GNIS feature 1662328 ID Website lacity.org Los Angeles ( i/lɔːs ˈændʒələs/, /lɔːs ˈæŋɡələs/ or i/lɒs ˈændʒəliːz/, Spanish: Los Ángeles [los ˈaŋxeles] meaning The Angels), officially the City of Los Angeles, often known by its initials L.A., is themost populous city in the U.S. -

A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante

But Why Glendale? But Why Glendale? A History of Armenian Immigration to Southern California Daniel Fittante Abstract: Despite its many contributions to Los Angeles, the internally complex community of Armenian Angelenos remains enigmatically absent from academic print. As a result, its history remains untold. While Armenians live throughout Southern California, the greatest concentration exists in Glendale, where Armenians make up a demographic majority (approximately 40 percent of the population) and have done much to reconfigure this homogenous, sleepy, sundown town of the 1950s into an ethnically diverse and economically booming urban center. This article presents a brief history of Armenian immigration to Southern California and attempts to explain why Glendale has become the world’s most demographically concentrated Armenian diasporic hub. It does so by situating the history of Glendale’s Armenian community in a complex matrix of international, national, and local events. Keywords: California history, Glendale, Armenian diaspora, immigration, U.S. ethnic history Introduction Los Angeles contains the most visible Armenian diaspora worldwide; however yet it has received virtually no scholarly attention. The following pages begin to shed light on this community by providing a prefatory account of Armenians’ historical immigration to and settlement of Southern California. The following begins with a short history of Armenian migration to the United States. The article then hones in on Los Angeles, where the densest concentration of Armenians in the United States resides; within the greater Los Angeles area, Armenians make up an ethnic majority in Glendale. To date, the reasons for Armenians’ sudden and accelerated settlement of Glendale remains unclear. While many Angelenos and Armenian diasporans recognize Glendale as the epicenter of Armenian American habitation, no one has yet clarified why or how this came about. -

Los Angeles Bibliography

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN THE LOS ANGELES METROPOLITAN AREA Compiled by Richard Longstreth 1998, revised 16 May 2018 This listing focuses on historical studies, with an emphasis is on scholarly work published during the past thirty years. I have also included a section on popular pictorial histories due to the wealth of information they afford. To keep the scope manageable, the geographic area covered is primarily limited to Los Angeles and Orange counties, except in cases where a community, such as Santa Barbara; a building, such as the Mission Inn; or an architect, such as Irving Gill, are of transcendent importance to the region. Thanks go to Kenneth Breisch, Dora Crouch, Thomas Hines, Greg Hise, Gail Ostergren, and Martin Schiesl for adding to the list. Additions, corrections, and updates are welcome. Please send them to me at [email protected]. G E N E R A L H I S T O R I E S A N D U R B A N I S M Abu-Lughod, Janet, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's Global Cities, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999 Adler, Sy, "The Transformation of the Pacific Electric Railway: Bradford Snell, Roger Rabbit, and the Politics of Transportation in Los Angeles," Urban Affairs Quarterly 27 (September 1991): 51-86 Akimoto, Fukuo, “Charles H. Cheney of California,” Planning Perspectives 18 (July 2003): 253-75 Allen, James P., and Eugene Turner, The Ethnic Quilt: Population Diversity in Southern California Northridge: Center for Geographical Studies, California State University, Northridge, 1997 Avila, Eric, “The Folklore of the Freeway: Space, Culture, and Identity in Postwar Los Angeles,” Aztlan 23 (spring 1998): 15-31 _________, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles, Berkeley: University of California Pres, 2004 Axelrod, Jeremiah B. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

Michael Govan Is the CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Michael Govan is the CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Since coming to LACMA in 2006 he has overseen the transformation of the 20–acre campus with buildings by Renzo Piano and monumental artworks by Chris Burden, Michael Heizer, Robert Irwin, Barbara Kruger, and others. At LACMA, Govan has pursued his vision of contemporary artists and architects interacting with the museum’s historic collections, as evidenced by exhibition and gallery designs in collaboration with artists John Baldessari, Jorge Pardo, and Franz West, and architects Frank O. Gehry, Fred Fisher, Michael Maltzan, and others. Under his leadership, LACMA has acquired nearly 35,000 works, building and expanding its collection of works from Latin America, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific. In 2015, Govan undertook the museum’s most successful art gift campaign in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary, as well as the most significant bequest in the museum’s history, the Perenchio collection of Impressionist and early 20th-century art. Known as well for his curatorial work, Govan has co-curated a series of notable exhibitions including Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time (2016–17), James Turrell: A Retrospective (2013–14), and The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA (2013), which presented plans for a future building for the museum designed by the Pritzker Prize–winning architect. Govan was the co- curator of the touring exhibition Dan Flavin: A Retrospective, organized by Dia:Beacon in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The exhibition concluded its international tour at LACMA, where it was on view, May 13–August 12, 2007. -

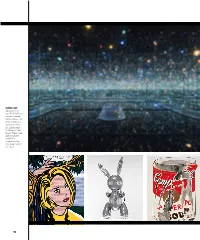

On the Scene at Coachella 2016 ICONIC ART (Clockwise from Top

ICONIC ART (Clockwise from top) You’ll find Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away,” Roy Lichtenstein’s “I...I’m Sorry!,” Jeff Koons’ “Rabbit” and Andy Warhold’s “Small Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Pepper Pot) at The Broad. Mark On the scene at Coachella 2016 98 Making a THESE FOUR GREAT SHAPERS EXPLAIN HOW THEY ARE PROGRESSING THE ART SCENE IN LOS ANGELES, THE CITY OF CONTINUOUS YOUTH AND ADAPTATION MaBY MARINE TANGUY rk There is no question that the current art world is evolving. From the rise of startups challenging the existing gallery model to a possible regulation of the market, we are entering a new era in the field. As always, with change, there are those who embrace it and those who fear it. But while the renowned art scenes of London and New York struggle to break their tradition and pre-establishment, L.A. is stepping up and becoming a lab for innovation and experimentation. Here’s to the bold and the visionaries—we have a lot to learn from them. PHOTOS COURTESY OF YAYOI KUSAMA/DAVID ZWIRNER, ROY LICHTENSTEIN/ ZWIRNER, ROY KUSAMA/DAVID OF YAYOI COURTESY PHOTOS STUDIO AND M. PARKER JEFF KOONS/DOUGLAS STUDIO, DOUGLAS M. PARKER INC./ ARTS, THE VISUAL FOR FOUNDATION WARHOL ANDY WARHOL/THE ANDY CAMPBELL TRADEMARKS USED WITH PERMISSION OF ARIST RIGHTS SOCIETY, CAMPBELL SOUP COMPANY 99 THE LOS ANGELES ART COLLECTORS ing ones, Edythe responds, “We have a long cessible to the public, so we decided to build ELI AND EDYTHE BROAD history of supporting public museums—Eli The Broad, endow it, fill it with our collection The Broads have about 2,000 works in was the founding chairman of MOCA and a and offer free general admission as a gift to their collection, one of the most prominent life trustee of MOCA, LACMA, MOMA. -

The Long Fight for Michael Heizer's "City"

Blouin Artinfo April 1, 2015 GAGOSIAN GALLERY The Long Fight for Michael Heizer’s “City” Mostafa Heddaya Michael Govan (left) and Michael Heizer on opening day of “Levitated Mass” at LACMA. (Photo by Stefanie Keenan) “To remove the work,” the artist Richard Serra famously quipped in a 1984 letter to the bureaucrats who commissioned his then-embattled “Tilted Arc” in New York’s Federal Plaza, “is to destroy the work.” For Serra and others whose art responds to site, the integrity of the work’s environment is vital. But as site expands beyond the narrow confines of the city, as in much of the land art that emerged in the 1960s and ‘70s, blocks dissolve into landscape, pedestrians to pipelines, and property lines alone become insufficient boundaries for preserving an overall artistic vision. With the passage of time, this sets up an inevitable collision between the expansive claims of certain works of land art, no matter how remote, and the human laws and conditions that govern their existence in the world. This has meant, for example, the decades of patient viewshed acquisitions carried out by the Dia Art Foundation in stockpiling parcels of ranchland surrounding Walter de Maria’s “Lightning Field” in Western New Mexico, or the intricate leasehold negotiations that ensured the unmolested survival of Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” on the shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Today, Michael Heizer’s “City” in Nevada is the most daunting of these pale elephants, the complexity of the challenges it faces matched by the unprecedented monumentality of its concrete, bunker-like sculptures. -

James Turrell's New Masterpiece in the Desert,' the Wall Street Journal Magazine, January 14, 2019

Press Reviews Cheshes, Jay. ‘James Turrell's New Masterpiece in the Desert,' The Wall Street Journal Magazine, January 14, 2019. WSJ. MAGAZINE James Turrell’s New Masterpiece in the Desert The artist has dedicated half his life to creating a massive—yet largely unseen—work of art. After more than four decades, he reveals a new master plan to the public MAPPED OUT “I don’t want people to come here, see it once, and then you’ve checked it o your bucket list and can forget it,” says James Turrell, surrounded by Roden Crater blueprints, “so you have to have an ongoing program.” PHOTO: ALEC SOTH FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE By JAY CHESHES Jan. 14, 2019 10 34 a.m. ET ON A CLOUDLESS afternoon in late September, the artist James Turrell rounds the crest of a hill just below Arizona’s Sunset Crater Volcano, a national monument, slowing his gray Jeep Cherokee under its cinder cone. Black shards of ancient lava are shingled across the landscape like carbonized roof tiles. “I’ll show you how I first saw Roden Crater,” he says, looking to the horizon and recalling the moment in 1974 that would shape his artistic career for the next 45 years. 1/10 “It was November, right before Thanksgiving,” he says. Turrell, an expert pilot, had spent months by then tearing through a $10,000 Guggenheim grant— soaring over the landscape in his 1967 Helio Courier H295, eyeing every butte and extinct volcano west of the Rockies, searching for the perfect site on which to build a monumental work of art. -

Reflecting Los Angeles, Decentralized and Global Los Angeles County Museum of Art

CASE STUDY Reflecting Los Angeles, Decentralized and Global Los Angeles County Museum of Art January 23, 2017 Liam Sweeney The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Copyright 2018 The Andrew W. Mellon endeavors to strengthen, promote, Foundation.. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- and, where necessary, defend the NonCommercial 4.0 International contributions of the humanities and License. To view a copy of the license, the arts to human flourishing and to please see http://creative- the wellbeing of diverse and commons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. democratic societies. The Mellon Foundation encourages distribution of the report. For questions, please write to [email protected]. Ithaka S+R provides research and strategic guidance to help the academic and cultural communities serve the public good and navigate economic, demographic, and technological change. Ithaka S+R is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that works to advance and preserve knowledge and to improve teaching and learning through the use of digital technologies. Artstor, JSTOR, and Portico are also part of ITHAKA. LACMA: REFLECTING LOS ANGELES, DECENTRALIZED AND GLOBAL 1 The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is distinguishable from other US encyclopedic museums in three aspects: it is the largest North American art museum west of the Mississippi; it is the youngest encyclopedic museum in the United States; and it is situated in one of the most ethnically diverse metropolises in the world. These characteristics interact in a number of meaningful ways under the museum’s current leadership, allowing its local and global ambitions to complement one another. -

Architecture and Engineering Theme: Period Revival, 1919-1950 Theme: Housing the Masses, 1880-1980 Sub-Theme: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Architecture and Engineering Theme: Period Revival, 1919-1950 Theme: Housing the Masses, 1880-1980 Sub-Theme: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources JANUARY 2016 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Architecture and Engineering/Period Revival; Housing the Masses/Period Revival Neighborhoods TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 CONTRIBUTORS 3 INTRODUCTION 3 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 THEME: PERIOD REVIVAL, 1919-1950 11 SUB-THEME: French Norman, 1919-1940 11 SUB-THEME: Storybook, 1919-1950 15 SUB-THEME: Late Tudor Revival, 1930-1950 20 SUB-THEME: Late Gothic Revival, 1919-1939 24 SUB-THEME: Chateauesque, 1919-1950 29 THEME: HOUSING THE MASSES, 1880-1980 33 SUB-THEME: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 33 SUB-THEME: Period Revival Multi-Family Residential Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 39 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 44 Page | 2 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Architecture and Engineering/Period Revival; Housing the Masses/Period Revival Neighborhoods PREFACE These themes are components of Los Angeles’ citywide historic context statement and provide guidance to field surveyors in identifying and evaluating potential historic resources relating to Period Revival architecture. Refer to www.HistoricPlacesLA.org for information on designated resources associated with these themes as well as those identified through SurveyLA and other surveys. CONTRIBUTORS Teresa Grimes and Allison Lyons, GPA Consulting. Ms. Grimes is a Principal Architectural Historian at GPA Consulting. She earned her Master of Arts degree in Architecture from the University of California, Los Angeles and has over twenty-five years of experience in the field. Ms.