RICHARD FOX "Plan B!" Richard Fox Turns on the Speed in an Attempt to Make up for a Penalty He Has Just Taken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kanu: Olympische Siegerehrung Der Schwaben-Ritter Erscheint 6X Im Jahr

Abteilungen: RUNDSCHAU DES TSV 1847 SCHWABEN AUGSBURG Badminton · Basketball · Boxen · Eistanz Nr. 5, Oktober 2012, 62. Jahrgang Faustball · Fechten · Fußball · Hockey TSV Schwaben Augsburg, Kanu · Leichtathletik · Tennis · Tischtennis Stauffenbergstr. 15, 86161 Augsburg Turnen · Wintersport Mitgliederstand: 01.01.12 = 2.674 Beitragsänderung: Euroumstellung 01.01.02 Schwaben-Highlight Wahlperiode: 3 Jahre Nächste Wahlen: 2014 Vereinsfarben: lila-weiß Ehrenmitglieder: Karl Heinz Englet (1964), Heidi Grundmann-Schmid (1995), Elisabeth Micheler-Jones (1995), Oliver Fix (1997), Elfriede Weis (1997), Alexander Grimm (2008) Gold. Standplakette: Winfried Krenleitner (1976), Manfred Fischer (1977) Die Vereinsführung des TSV 1847 Schwaben Augsburg und dessen Turn- und Sportstätten-Bauvereins Vereinsführung: Präsident: Hans-Peter Pleitner, 86161 Augsburg, Sanderstraße 47, Tel. 56 08 60, Fax 5 60 86 34 1. Stellvertreter:: Gerhard Benning, 86356 Neu- säß, Biburger Str. 6b, Tel. 34 6160, Fax 3 4616 20 Schatzmeister: Heinz Hielscher, 86165 Augsburg, Schneelingstr. 10 a, Tel. 5 09 01-0, Fax 5 09 01-11 Verwaltungs- und Wirtschaftsbeirat: Karl Heinz Englet, Helmut Kahn, Dr. Peter Kahn, Bernd Kränzle, Eberhard Schaub, Harry Schenavsky, Johannes Schrammel, Gottfried Selmair Geschäftsstelle: Frau Eva Kalfas und Frau Karin Wiechert Vereinsheim Stauffenbergstr. 15, 86161 Augsburg, Tel. 5718 47, Fax 59 59 01, Mo., Di., Do., Fr. von 10–12 Uhr, zusätzlich Do. von 16–18 Uhr, Mittwoch geschlossen E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.tsv-schwaben-augsburg.de Konto: Stspk. Augsb., Kto.-Nr. 0 605 915, BLZ 720 500 00. Vereinsgaststätte: „Schwabenhaus“, Stauffenbergstraße 15, 86161 Augsburg, Tel. 57 37 57. Der Schwaben-Ritter, gegr. 1951 von A. Beltle und H. Weig. Herausgeber: TSV 1847 Schwaben Augsburg e.V., 86161 Augsburg, Stauffenbergstraße 15. -

Canoe Kayak 1989

C_JNOE"IAYAK.189 U;I £2.00. u.s $ s.oo. D.M 7. oo~: . ~. _r. .r " J-- ::t :-<..'.".~;r;,,:.- ,\:- -L-·J' ~. J'J j .r.. ~ J ___r.,J._• ~---~ @- ,!.~..!...-!JJ~J ..D _; j . jJ.!J ~_l.-.;. !:.J.~iJ perception REFLEX ~!- ~.- L.~!-~r ?\. -----""-~ The Art of Slalo •••. REFLEX: Winner of Every Major Slalom Title in 1 988 vvorld Cup. Europa Cup, British Slalom Champion. perception® Kayaks A divison of &AYBD Limited Bellbrook Industrial Estate, Bell Lane, )I{ Uckfield, East Sussex TN22 1 QL. Tel: (0825) 5891/2 CANOE KAYAK'II I I 4 WHYCANOE 14 SAVAGE KAYAK89? WORLDS 89 22 How and why it came together. 1989 Worlds - An inside view from Bill Endicott. OLYMPICS 5 CANOE SLALOM 1972 Oly"1)icS - TAKES OFF The first Olympic Slalom 15 by John Mac Loed. 1988 World Cup report PULL-OUT by Richard Fox. POSTER BARCELONA 8 WORLD CUP Great Bnuan's The build up to the World Champioins 1992 Olympics. RESULTS in full colour 9 l- ~1 MELVIN 19 PADDLER JONES PROFILES. 'I PROFILE TRAINING EATING SLEEP• ING DRINKING ****ING. CANOE KAYAK189 asked Melvin about his crash course to the top.he sucessful season and his rise in slalom. • 12 28 RANKINGS British slalom rankings for the 1989 - . '89 WORLD'S season. SAVAGE RIVER USA Iii COVER SAVAGE! -!A. .. ,' Richardson and Thompson Information for paddlers and Coaching the Mens K1 C2 British Champions supporters. by Hugh Mantle. Photo:Pete Astles Publlaher / Editor Mke Druce 0..lan Gordon Druce. CANOE KAYAK '81 Contrlbutln1 Wrtten - Richard Fox, Bil Endicott, John Macloed, Hugh Mantle, John Gosq, N>lished by CANOE KAYAK '89. -

2015 – 2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT PRINCIPAL PARTNER Contents Message from the ASC Our Partners in Sport Our Year in Focus 02 03 04 04 President’s Report 06 Chief Executive’s Report Our People Our Award Winners Our Website 08 13 14 Our Members Our Performance Our Teams 17 31 52 17 Canoe South Australia 31 Olympic High Performance 19 Canoe Tasmania 36 Canoe Polo 21 Canoeing Victoria 38 Canoe Slalom 24 Canoeing Western Australia 41 Canoe Sprint 26 PaddleNSW 44 Canoe Marathon 28 Queensland Canoeing 47 Freestyle 48 Ocean Racing 50 Wildwater Our Participation Our Pathways Financial Statements 56 58 62 Australian Canoeing Ltd. presents this report to its members and external stakeholders for the purpose of reporting operational and financial performance for the period July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016. ABN 61 189 833 125, canoe.org.au - 2 - Message from the Australian Sports Commission The Australian Sports Commission (ASC) congratulates our National Sporting Organisations (NSOs) on their achievements this year. In particular, we congratulate all of our athletes who represented Australia in the Rio Olympic and Paralympic Games. You did so with great distinction. The country is proud of your commitment and dedication, and the manner in which you conducted yourself throughout the campaigns. In the aftermath of the Games, the Board of the ASC has re-committed to the core principles of Australia’s Winning Edge, the ASC’s ten year plan for high performance sport introduced in 2012. The four key principles are: high aspirations for achievement; evidence-based funding decisions; sports owning their own high performance programs; and a strong emphasis on improved leadership and governance. -

1984 Year Book

BRITISH CANOE UNION SLALOM YEARBOOK 1984 FLEXEL HOUSE, 45-47 HIGH STREET ADDLESTONE, WEYBRIDGE SURREY, KT15 1JV ., 1983 WORLD SLALOM CHAMPIONSHIPS - MERANO BRITISH RESULTS K1 MEN 1st Richard Fox Stafford & Stone 207.18 10th Jim Dolan Manchester 216.71 29th Paul Mcconkey Stafford & Stone 225.17 K1 LADIES 1st Liz Sharman Bury St. Edmunds 232.34 2nd Jane Roderick Stafford & Stone 236.34 6th Gail Allan Ambleside AAA 244.93 24th Sue Garriock Ribble 271.28 CANADIAN · C1 4th Peter Keane Luton 234.27 17th Jeremy Taylor Windsor 254.96 23rd Pete Bell Stafford& Stone 260.39 34th Martyn Hedges Windsor 279.93 CANADIAN · C2 7th Eric Jamieson & Robin Williams Wey 259.B6 16th Michael Smith & Andrew Smith Urchins/Windsor 272.12 20th Robert Joce & Robert Owen Paddington Bears 277.19 TEAM EVENTS K1M 1st R Fox, P Mcconkey, J Dolan 232.24 K1L 2nd L Sharman, J Roderick, S Garriock 285.51 C1 3rd M Hedges, P Keane, J Taylor 276.63 C2 3rd E Jamieson & R Williams, M Smith & A Smith, R Joce & R Owen 298.20 BRITISH MEDALS Gold Madel . Individual K1 Men Richard Fox Gold Medal - Individual K1 Ladies Elizabeth Sharman Silver Madel - Individual K1 Ladies Jane Roderick Gold Medal - K1 Men -Team Richard Fox Paul McConkey Jim Dolan Silver Medal · K1 Ladies - Team Liz Sharman Jane Roderick Susan Garriock Bronze Medal · C1 - Team Martyn Hedges Peter Keane Jeremy Taylor Bronze Medal - C2 • Team Eric Jamieson & Robin Williams Michael Smith & Andrew Smith Robert Joce & Robert Owen 93 BRITISH RESULTS - 1982 EUROPA CUP SLALOM NATIONS TROPHY 1st GREAT BRITAIN 2nd WEST GERMANY 3rd CZECHOSLOVAKIA INDIVIDUAL AND TEAM RESULTS K1M Richard Fox EUROPEAN CHAMPION K1 L Liz Sharman EUROPEAN CHAMPION C1 Martin Hedges 4th Overall - 1st European C2 Jock Young and Alistair Munro 5th Overall 1st EVENT - TACEN - YUGOSLAVIA K1L Gold Liz Sharman Silver Sue Garriock K1M Team Gold Fox/Dolan/Manwaring K1L Team Silver Sharman/Garriock/Wilson C1 Team Bronze Hedges/Doman/Taylor C2 Team Silver Young-Munro/Smith-Smith /Jamieson-Williams 2nd EVENT - LOFER -AUSTRIA K1M Gold Richard Fox K1L Gold Liz Sharman C2 Silver E. -

000 CANOEING at 1936-2008 OLYMPIC GAMES MEDAL

OLYMPIC GAMES MEDAL WINNERS Sprint and Slalom 1936 to 2008 1 MEDAL WINNERS TABLE (SPRINT) 1936 to 2008 SUMMER OLYMPICS Year s and Host Cities Medals per Event Gold Silver Bronze MEN K-1, 10 000 m (collapsible) 1936 Berlin, Gregor Hradetzky Henri Eberhardt Xaver Hörmann Germany Austria (AUT) France (FRA) Germany (GER) MEN K-2, 10 000 m (collapsible) 1936 Berlin, Sven Johansson Willi Horn Piet Wijdekop Germany Erik Bladström Erich Hanisch Cees Wijdekop Sweden (SWE) Germany (GER) Netherlands (NED) MEN K-1, 10 000 m 1936 Berlin, Ernst Krebs Fritz Landertinger Ernest Riedel Germany Germany (GER) Austria (AUT) United States (USA) 1948 London, Gert Fredriksson Kurt Wires Eivind Skabo United Kingdom Sweden (SWE) Finland (FIN) Norway (NOR) 1952 Helsinki, Thorvald Strömberg Gert Fredriksson Michael Scheuer Finland Finland (FIN) Sweden (SWE) West Germany (FRG) 1956 Melbourne, Gert Fredriksson Ferenc Hatlaczky Michael Scheuer Australia Sweden (SWE) Hungary (HUN) Germany (EUA) MEN K-2, 10 000 m 1936 Berlin, Paul Wevers Viktor Kalisch Tage Fahlborg Germany Ludwig Landen Karl Steinhuber Helge Larsson Germany (GER) Austria (AUT) Sweden (SWE) 1948 London, Gunnar Åkerlund Ivar Mathisen Thor Axelsson United Kingdom Hans Wetterström Knut Østby Nils Björklöf Sweden (SWE) Norway (NOR) Finland (FIN) 1952 Helsinki, Kurt Wires Gunnar Åkerlund Ferenc Varga Finland Yrjö Hietanen Hans Wetterström József Gurovits Finland (FIN) Sweden (SWE) Hungary (HUN) 1956 Melbourne, János Urányi Fritz Briel Dennis Green Australia László Fábián Theodor Kleine Walter Brown Hungary -

Canoe Focus Early Summer 2019 the 2019 Coaching and Leadership 23 Conference Returns This November

Adventure is... Read more on page 14 ICF Canoe Slalom World Cup, presented by Jaffa. Read more on page 6 & 7 Interview with Steve Backshall on his world first paddling expeditions Read more on page 8 Image credit: True to Nature Ltd Early Summer 2019 Ajay Tegala, National Trust Ranger In partnership with Wicken Fen Nature Reserve “When I get to be out on the water it’s such a relaxing moment, with the sound of the reeds going past. The general calmness of being on the water makes me feel very relaxed and content. I’m very lucky.” 15% discount for members of British Canoeing Full T&Cs apply. Not to be used in conjunction with any other offer or discount. Selected lines are exempt. Maximum 10% discount on bikes. Only valid upon production of your British Canoeing membership identification in-store or use of code online. Offer expires 31.12.19. You can also use your discount with: Trusted by our partners since 1974 Stores nationwide | cotswoldoutdoor.com Let’s go somewhere Contents 3 Welcome Go Paddling! Welcome note from Professor Record breaking numbers 4 13 John Coyne CBE take part in Go Paddling Week! News Adventure is... 14 News 5 Adventure is... p14 Fun in the sun at Paddle in the Park 2019! p5 Adventure Performance Adventures in film making 16 World Cup Highlights 6 Thank you Canoe Crew! 7 Adventures in film making p16 Our Partners World Cup Highlights p6 Jaffa - Word Search 18 Featured Interview Cotswold Outdoor - I am Ajay 20 Steve Backshall on paddling to Coaching and Leadership 8 rediscover the golden age of exploration Become a Stand Up Paddleboard Coach 22 Canoe Focus Early Summer 2019 Canoe Focus The 2019 Coaching and Leadership 23 Conference returns this November Steve Backshall on paddling.. -

Mag. Franz Zeilner, 13.09.1953 Universitätslektor an Der Universität Salzburg ( 1989 – 2009), Bmhs-Professor

Anmerkungen MAG. FRANZ ZEILNER, 13.09.1953 UNIVERSITÄTSLEKTOR AN DER UNIVERSITÄT SALZBURG ( 1989 – 2009), BMHS-PROFESSOR KANUSPORT (PADDELN): Als Wettkampf- und Freizeitsport Geschichte, Disziplinen, Technik, Sichern-Retten und Bergen, Materialkunde, Flusskunde, Kanusport und Umwelt, Kanutourismus, Kanuschulen und Vereine in Österreich. Lehr- und Lernunterlage für die Universitätslehrveranstaltung: Alpines Kajakfahren (Paddeln) für Studierende der Studienrichtungen Sportwissenschaften und Lehramt für höhere Schulen (Leibeserziehung bzw. Bewegung und Sport) 1 Anmerkungen INHALTSVERZEICHNIS A. DIE BEGRIFFE „KANU“ UND „KANUSPORT“ (PADDELSPORT) ........................ 3 B. GRUNDZÜGE DER GESCHICHTE DES KANUSPORTS. ......................................... 5 C. DIE ENTWICKLUNG DES KANUSPORTS IN SEINER HEUTIGEN FORM ......... 14 D. GROSSE INTERNATIONALE ERFOLGE ÖSTERREICHISCHER KANTUEN ..... 31 E. INDIKATIONEN UND KONTRAINDIKATIONEN FÜR DEN KANUSPORT ....... 35 F. DIE DISZIPLINEN IM KANUSPORT ......................................................................... 40 G. KENTERN UND SCHWIMMEN IM WILDFLUß, SICHERN, RETTEN UND BERGEN ................................................................................................................................ 77 H. DIE GESUNDHEITLICHEN ASPEKTE BEIM KANUSPORT .............................. 85 I. DAS ALPINE KAJAKFAHREN: DIE MATERIALKUNDE ...................................... 94 J. CHEMIE IM KANUSPORT: DIE VERWENDUNG VON POLYETHYLEN IM BOOTSBAU ....................................................................................................................... -

2009 Year Book

.. shop: holme pierrepont ,_ online: www.kayakstore.net mailorder: 0115 9813222 events: hydrasports Slalom Yearbook .~BUe':N~IO~N: . Cl 2009· - . td(f)(f)[fj /JJff)(l/J(JJU)fflll &/JJm@(J) !JrJJm~/JJ! J(J)~ ~ llmrJ@u1mmrJ!JrJJmmll m@~mllrJ~ {> f1(j)(j)(j) (J]!!J!JJ(j)f1 &J[!jjJ[L(j)J!j] W!!J!JJ&Ill!JJ® rLll&J;J 139 National Championships & Ranking Lists up until 1960 the National Champions were determined by one designated National Championship Slalom, and the Ranking list was quite separate. Those early National Champions were:- Year Venue Kt Men Kt Women 1958 Perth lain Carmichael No Champion (only two entries) 1959 Shepperton Paul Farrant Eva Barnett 1960 Llangollen Julian Shaw Heather Goodman From 1961, the National Champion was the person who came top of the ranking list Year Kt Men Kt Women Ct Women Ct Men C2 1961 lain Carmichael Margaret Bellord -/- 1962 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- 1963 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- 1964 Dave Mitchell Jean Battersby t" d Lesley Calverley} ,e -/- 1965 Dave Mitchell -/- 1966 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- 1967 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Mike Hillyard & Michael Ramsey 1968 Ken Langford Audrey Keerie Geoff Dinsdale Robin Witter & Rodney Witter 1969 Ray Calverley Heather Goodman Gay Goldsmith Robin Witter & Dave Swift 1970 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Jim Sibley Robin Witter & Rodney Witter 1971 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Rowan Osborne David Allen & Lindsay Williams 1972 Ray Calverley Pauline Goodwin Rowan Osborne David Allen & Lindsay Williams 1973 Ray Calverley Pauline Goodwin Rowan -

Kayak 2 Assessment Guide

Kayak Instructor – Level 2 Photo: Charlie Martin Assessment Guide For Assessors and Candidates Kayak Skills Instruction Kayak Level 2 - Assessment Guide © NZOIA Aug 2014 in conjunction with WWNZ Assessment Notes This Assessment Guide is to assist assessors with judging a candidate’s competency. All judgements must be based on current best practice and industry standards. This guide is also to help candidates know what they will be assessed on and what assessment tasks they will be asked to complete. Assessors use three types of direct evidence to judge a candidate’s competency: - Written questions / assignment - Oral questions and discussion - Observation of practical tasks Assessment - Kayak Skills Instruction Technical Competence 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the development of whitewater kayaking as a sport including current developments and trends The candidate will have understanding and awareness of: Competitive whitewater kayaking and the areas used for these events in New Zealand The variety of types of whitewater kayaking currently undertaken in New Zealand e.g. slalom, freestyle, extreme racing, multisport Identify and critique learning resources for kayak instruction/techniques 2. Demonstrate intermediate freestyle moves The candidate will role model intermediate freestyle moves (i.e. making good visual images suitable for students to learn from). These may include, but are not limited to: Surfing; carving, flat-spin, blunt Hole riding; maneuver, roll, spin, cartwheel, blast Eddy-line; stern squirt, screw up, stalls, cartwheel Note: Candidates are not expected to be able to ‘role model’ all these techniques. It is expected you could perform them to a level which can ‘enhance’ a student’s river running and river play options. -

1995 Year Book

National Championships & Ranking Lists up until 1960 the National Champions were determined by one designated National Championship Slalom, and the Ranking list was quite separate. Those early National Champions were:- Year Venue K1 Men K1 Women 1958 Perth lain Carmichael No Champion (only two entries) 1959 Shepperton Paul Farrant Eva Barnett 1960 Llangollen Julian Shaw Heather Goodman From 1961, the National Champion was the person who came top of the ranking list Year K1 Men K1 Women CJ C2 1961 lain Carmichael Margaret Bel lord -/- 1962 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- 1963 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- ~ 1964 Dave Mitchell Jean Battersby }tied Lesley Calverley -/- 1965 Dave Mitchell -/- 1966 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman -/- 1967 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Mike Hillyard & Michael Ramsey 1968 Ken Langford Audrey Keerie Geoff Dinsdale Robin Witter & Rodney Witter 1969 Ray Calverley Heather Goodman Gay Goldsmith Robin Witter & Dave Swift 1970 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Jim Sibley Robin Witter & Rodney Witter 1971 Dave Mitchell Heather Goodman Rowan Osborne David Allen & Lindsay Williams 1972 Ray. Calverley Pauline Goodwin Rowan Osborne David Allen & Lindsay Williams 1973 Ray Calverley Pauline Goodwin Rowan Osborne David Allen & Lindsay Williams 1974 Ray Calverley Peggy Mitchell Malcolm Pearcey Jim Sibley & Terry Hewett 1975 Nicky Wain Julia Harling Martyn Hedges Mick Philip & Les Purdy 1976 Martyn Peters Julia Harling Martyn Hedges Dave Brown & Dave Curle 1977 Nicky Wain Julia Harling Martyn Hedges Les Williams & Dave Howe -

Interview Simon Westgarth

Interview Simon Westgarth One of the early fi gures in freestyle kayaking, Simon Westgarth has turned his love for kayaking into a full-time profession. Through owning a company, KS: Your main gig now is teaching kayaking and run- KS: Your approach to teaching is very personal, but KS: Are there any paddlers in particular who you ning guided paddling tours. How did this evolve? surely you can’t run all your programmes single-han- look up to for inspiration? making kayaking fi lms, and SW: Running Gene17kayaking is now my main job, dedly. Who are the people you work most closely SW: I am very lucky in that I have paddled with most although I shoot and edit video for Westgarth TV, with? of the player’s of my generation and with the old teaching, Simon is all about but the time spent on this is becoming increasingly SW: Gene17’s top team are Deb Pinniger and Dave Car- guard. Mick Hopkinson is iconic, a new school paddler squeezed. roll, both of whom are amazing individuals and great in his late 50’s, always moving forward. I enjoy time introducing more and more paddlers. As the business has expanded, Olli Grau and with Olli Grau for the straight talking and plain ac- Matt Tidy have joined us for specifi c programmes. tion, a long time friend Cody ‘the outlaw’ Boger from people to paddling. With KS: So what is Gene17kayaking? Starting next year, Leo Hoare, a highly regarded UK Canada, who is a pure lifestyler and Dan Gavere for SW: Gene17kayaking, is a high end whitewater kaya- coach trainer will head up our Instructor Training Pro- showing that you can always keep learning no matter a main operation on the king trip and paddling adventure provider, where we gramme (D4DR WW) based in Slovenia. -

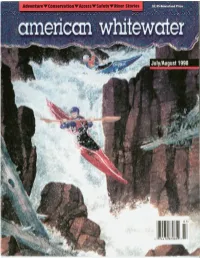

Kayaking Event Hosted by Your Commu- Immediately

Letters ......................................7 Forum ...................................... 4 r Blame by Bob Gedekoh Briefs .....................................76 r Membership Maniacs Wanted Portrait of a Whitewater r A Beginner Dream Come True r North American Water Trails COnferenCt! Artist... Meet Movt Reel r Watauga Gorge Race by Bob Gedekoh 38 r Ocoee Double Header River Voices ................................... 64 New River DrysY by Tim Daly 46 r A Letter from Rosl r First Swim r ~i~~ingHer softly ... r The Wet Ones CotingI u with Cabin Fever r The Lek Hole by Rick Danis 49 r Waller's Rules of the River r Whitewater in Belgium? A Rite of Friendship... Conservation .................................. 16 r Director's Cut Paddling the Rocky Broad r Profile: Kevin Lewis r Smell the Flowers Remembering Pablo Perez V r Rivers: The Future Frontier by Leland Davis 52 Safety .................................... 62 Cover: Painting donated to American Whitewater by Hoyt r Who We Are, and What We Do Reel ... to be sold at Gauley Fest 1998. See story inside. by Rich Bowers Publication Title: American Whitewater Access .................................. 25 Issue Date: July/ August 1998 Statement of Frequency: Published bimonthly r Girl Scouts Towed While Rafting Authorized Organization's Name and Address: r Oregon Rules American Whitewater Nature Lovers vs. Developers P.O. Box 636 r Margretville, NY 12455 r Help the Grand Canyon Events .................................. 32 r AWA Events Central r 1998 Schedule of River Events r 1998 NOWR Events Results Printed on Recycled Paper American Whitewater July/ August 1998 cheap, sarcastic, and lazy): my tendency to blame other people for my misfortunes. This is a failing that my mother decried when I was still a child.