MOTIVATION of FIRST TIME MARATHONERS to ADHERENCE to MARATHONING a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Virgin Money London Marathon Sunday 3Rd October 2021

Virtual Virgin Money London Marathon rd Sunday 3 October 2021 Charity Reg. No: 266071 General Information The London Marathon is one of the biggest running events in the world. The race is currently sponsored by Virgin Money and named the Virgin Money London Marathon. It is set over a largely flat course around the River Thames, beginning at three separate points around Blackheath finishing in the Mall alongside St. James’s Park. In addition to being one of the top five international marathons run over the traditional distance of 26 miles and 385 yards, (42.195km) the London Marathon is also a large celebratory sporting festival with around 50,000 amateur, club and fun runners taking part in the event this year. Many of these participants run to raise money for their favoured charities. Since 1981 the event has raised over £1 billion for charity. All the information you need to apply for a Paget’s Golden Bond place to run in the Virgin Money London Marathon is listed below. Should you require further information however, please contact the Paget’s office on 0161 799 4646 or email: [email protected] • The Paget’s Association has a limited number of Golden Bond places and usually has more applications than places available • Selection will be based on the information given on your application form, so please give as much information as possible • The selection for places will be made by a judging panel and applicants will be notified of the outcome as soon as possible • All successful applicants will be required to pledge that they will raise a minimum of £1,000 in sponsorship • Successful applicants will be required to pay a non-refundable £50 registration fee to secure their place (only payable once a Golden Bond place has been allocated) • We ask that Golden Bond runners submit their fundraising target by 30th November 2021 • The Paget’s Association does not include Gift Aid in the sponsorship total. -

Improved Race Times in Marathoners Older Than 75 Years in the Last 25 Years in the World's Largest Marathons

Chinese Journal of Physiology 59(3): 139-147, 2016 139 DOI: 10.4077/CJP.2016.BAE382 Improved Race Times in Marathoners Older than 75 Years in the Last 25 Years in the World’s Largest Marathons Baschir Ahmadyar, Thomas Rosemann, Christoph Alexander Rüst, and Beat Knechtle Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Gesundheitszentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland Abstract Performance trends of elite marathoners are well investigated. However, performance of elderly marathoners (> 75 years) competing in the world’s largest city marathons is not well-known. We exam- ined marathon race data of 1,691 marathon finishes (i.e. 218 women and 1,473 men) competing between 1990 and 2014 in 5-year age groups 75-79, 80-84, 85-89, and 95-99 years in four races (Berlin, New York, Chicago and Boston) of the ‘World Marathon Majors’. The number of female (r2 = 0.50, P < 0.0001) and male (r2 = 0.88, P < 0.0001) finishers increased significantly across years. The number of women (r2 = 0.36, P = 0.0019) and men (r2 = 0.88, P < 0.0001) in age group 75-79 years increased. In age group 80-84 years, the number of women (r2 = 0.36, P = 0.0111) and men (r2 = 0.54, P < 0.0001) also increased. In age groups 85-89 to 95-99 years, however, the number of female and male finishers remained unchanged. Across years, women (r2 = 0.26, P = 0.0090) and men (r2 = 0.31, P = 0.0035) reduced their race times. Women and men in age group 75-79 years improved race times. -

Table of Contents

Media Table of contents Media information & fast facts ......................................................................................................... 3 Important media information ....................................................................................................................................................4 Race week Media Center..............................................................................................................................................................4 Race week schedule of events ..................................................................................................................................................7 Quick Facts ...........................................................................................................................................................................................8 Top storylines ......................................................................................................................................................................................10 Prize purse .............................................................................................................................................................................................13 Time bonuses ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Participant demographics ............................................................................................................................................................15 -

Volume 130, Number 29

WEATHER, p. 2 WED: 90°F | 78°F MIT’s Sunny Oldest and Largest THU: 88°F | 74°F Newspaper Partly cloudy FRI: 89°F | 72°F Sunny Volume 130, Number 29 tech.mit.edu Wednesday, July 7, 2010 After three days in court, Lady Gaga pops by MIT Tang trial postponed Shows her teeth for giant Polaroid Styke testifies, trial likely to resume in fall By John A. Hawkinson Informing the court that NEWS EDITOR the Commonwealth-appoint- ed psychiatrist had reversed The trial of Anna L. Tang her opinion on Tang’s crimi- — the Wellesley College nal responsibility on the “eve student who stabbed MIT before the last day” of the tri- student Wolfe B. Styke ’10 al, defense attorney Robert A. in October 2007 — began George moved to suspend the last month, and came to an trial to allow time to prepare, abrupt halt on its third day and Judge Bruce R. Henry al- last week Wednesday. lowed it. A status conference is set for August 17, and the trial is LEAH BRUNETTo—THE TECH likely to be rescheduled for appreciate the wrongfulness sometime after that date in of her behavior and lacked September. the ability to conform her be- The Commonwealth’s havior to the requirements of forensic psychiatrist in the the law. case, Dr. Alison Fife, had On the basis of the Fife submitted a report to the report, Tang waived her right Court in May indicating that to a jury trial and proceeded she believed Tang was not with a bench trial before the criminally responsible for the stabbing: that Tang did not Tang, Page 13 LEAH BRUNETTo—THE TECH ERIC D. -

Chicago Year-By-Year

YEAR-BY-YEAR CHICAGO MEDCHIIAC INFOAGO & YEFASTAR-BY-Y FACTSEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR-BY-YEAR HISTORY 2011 Champion and Runner-Up Split Times .................................... 126 2011 Top 25 Overall Finishers ....................................................... 127 2011 Top 10 Masters Finishers ..................................................... 128 2011 Top 5 Wheelchair Finishers ................................................... 129 Chicago Champions (1977-2011) ................................................... 130 Chicago Champions by Country ...................................................... 132 Masters Champions (1977-2011) .................................................. 134 Wheelchair Champions (1984-2011) .............................................. 136 Top 10 Overall Finishers (1977-2011) ............................................. 138 Historic Event Statistics ................................................................. 161 Historic Weather Conditions ........................................................... 162 Year-by-Year Race Summary............................................................ 164 125 2011 CHAMPION/RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS 2011 CHAMPION AND RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS MEN MEN Moses Mosop (KEN) Wesley Korir (KEN) # Name Age Country Time Distance Time (5K split) Min/Mile/5K Time Sec. Back 1. Moses Mosop ..................26 .........KEN .................................... 2:05:37 5K .................00:14:54 .....................04:47 -

2021 Virgin Money London Marathon Oxfam's Charity Place Terms And

2021 Virgin money London Marathon Oxfam’s charity place Terms and Conditions The Virgin Money London Marathon is one of Oxfam’s most important fundraising events. We need all our charity place runners to honour their pledge and raise a minimum of £2000 before 03 November 2021. These terms and conditions are to ensure that we can support our runners in the best possible way, while raising as much money as possible for our life-saving work to tackle poverty and reduce inequality. What you can expect from Oxfam • Once you have applied for an Oxfam charity place in the 2021 Virgin Money London Marathon, your application will be assessed by the Oxfam Challenge Events Team. You will be informed of the outcome of your application by telephone or email within a month of submitting your application. We receive far more applications than we have available race places, so unfortunately not everyone who applies will be given a place. • Once you have been offered a place, agreed to the fundraising pledge and paid your entry fee, Oxfam will reserve a charity place for you. However, Oxfam has the right to revoke your place in exceptional circumstances, including any event cancellations in any year due to coronavirus. • We will send you a fundraising pack which contains information about training and fundraising, and an Oxfam vest or t-shirt to wear on race day. • We will send you regular support emails to help with your training and fundraising. These are classed as administrative emails and as such do not require separate marketing consent. -

Essays on Competitive Strategy and Innovation Management by Richard

Essays on Competitive Strategy and Innovation Management by Richard Dick Wang A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Paul J. Gertler, Chair Professor John Morgan Professor Yingyi Qian Fall 2010 Essays on Competitive Strategy and Innovation Management Copyright 2010 by Richard Dick Wang Abstract Essays on Competitive Strategy and Innovation Management by Richard Dick Wang Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration University of California, Berkeley Professor Paul J. Gertler, Chair This dissertation examines product positioning and development strategies by firms. Product strategies not only determine a firm’s performance, but they also influence the types of goods that are available in the market. I conduct empirical evaluations on how rivalries shape product decisions, and propose a framework that guides firms to devise incentive schemes to spur new ideas which are vital to the development of innovative products. I begin by focusing on product differentiation strategy among rivals. I develop a theoretical model on programming choice by rival broadcasters in the media industry. The model predicts that the level of product differentiation is determined by the relative strengths of the rivals. I test this model using data from the Chinese satellite television industry. I analyze dynamic product positioning activities of 30 satellite television channels with respect to their dominant rival. Consistent with theory, the empirical evidence shows that weaker firms are more responsive when compared to the stronger ones to differentiate their products from the dominant rival. -

HCMC 2008 Survey Summary

5/11/2008 14:38:00 Harvard College Marathon Challenge Post-Event Survey Summary 2008 Questions/Complaints/Blame? E-Mail [email protected] Website: http://marathon.harvard.edu ©2008 Harvard College Marathon Challenge. Reproduction, distribution, or any other use of this data, in whole or in part, is prohibited without express written consent from Harvard College Marathon Challenge. 1 OVERVIEW: HARVARD COLLEGE MARATHON CHALLENGE (HCMC) Harvard College Marathon Challenge (HCMC) started in 2005. HCMC participants raise money for Project HEALTH and Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA), two charities that mean a great deal to many Harvard students and employees. In exchange for their successful fundraising efforts, HCMC participants receive official invitational entries (numbered bibs) to run in the Boston Marathon. These invitation entries allow participants to run the Boston Marathon at their own pace; they are exempt from the time-qualifying requirement by virtue of their charitable fundraising efforts. In 2007-08, HCMC participants raised approximately $45,000 to benefit PBHA and Project HEALTH. To ensure diversity, HCMC participants were selected by a process that took into account student vs. staff status, year of graduation, residential affiliation, past PBHA/Project HEALTH involvement, gender, previous running/marathon experience, and especially demonstrated prior commitment to the HCMC program. Each participant paid a nonrefundable registration fee and met several interim fundraising benchmarks, culminating in a final fundraising benchmark that ranged from $750 for participants who joined very late – some less than two weeks before the Marathon – to $2500 for undergraduate "veteran" participants. Throughout the months prior to the Marathon, participants used the HCMC listserv as arrange training runs and to discuss a wide range of training, fundraising, and related issues. -

Northbrook Newsletter -Mar 2003

Northbrook Newsletter -Mar 2003 Men’s X-country Race, Mar 1st, 2003. March’s Newsletter So while any sport needs new young recruits to eventually fill the ranks both Northbrook and running This is the third newsletter in the last 4 months. That’s more in general continue to thrive on the middle aged. than we have had over the last 18 months so I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has helped and I decided to undertake a little research into the local supported this so far – your help is appreciated. vets scene and contacted the secretary of the Midlands Veterans Athletic Club that you can join if Please keep those articles, race results etc. coming. you are over the age of 40 for men and 35 for women. Members enjoy regular newsletters, which Thanks to all our contributors this month. inform you of area, national and international competition specifically for veterans. These events Well done to the February winner of runner of the month, cover cross-country, road races from 5k to marathon Sarah Edkins. distances and track and field events. The subscription is £8 per annum and if you are interested in joining I have some application forms so please let me know. Veterans News As you will be aware the relay season is approaching Alex Marshall and a date for your dairy is Saturday 17th May when After several years of sterling work, Dave New has stepped the National Open Masters Road Relay down from the committee and I have taken on the role of vets Championships will be held at Sutton Park captain. -

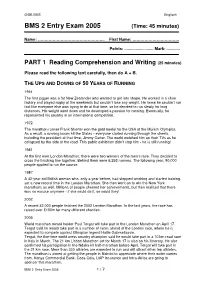

BMS 2 Entry Exam 2005 (Time: 45 Minutes)

GIBB BMS Englisch BMS 2 Entry Exam 2005 (Time: 45 minutes) Name: ………………………………………….. First Name: …………………………….. Points: .......................... Mark: ............ PART 1 Reading Comprehension and Writing (25 minutes) Please read the following text carefully, then do A + B. THE UPS AND DOWNS OF 50 YEARS OF RUNNING 1951 The first jogger was a fat New Zealander who wanted to get into shape. He worked in a shoe factory and played rugby at the weekends but couldn’t lose any weight. He knew he couldn’t run fast like everyone else was trying to do at that time, so he decided to run slowly for long distances. His weight went down and he developed a passion for running. Eventually, he represented his country in an international competition. 1972 The marathon runner Frank Shorter won the gold medal for the USA at the Munich Olympics. As a result, a running boom hit the States - everyone started running through the streets, including the president at that time, Jimmy Carter. The world watched him on their TVs as he collapsed by the side of the road. This public exhibition didn’t stop him - he is still running! 1981 At the first ever London Marathon, there were two winners of the men’s race. They decided to cross the finishing line together. Behind them were 6,253 runners. The following year, 90,000 people applied to run the course. 1987 A 42-year old British woman who, only a year before, had stopped smoking and started training, set a new record time in the London Marathon. She then went on to win the New York marathons as well. -

2011 London Marathon London Marathon London Marathon

2011 London Marathon Statistical Information Men London Marathon All Time list Performances Time Performers Name Nat Place Date 1 2:05:10 1 Samuel Wanjiru KEN 1 26 Apr 2009 2 2:05:15 2 Martin Lel KEN 1 13 Apr 2008 3 2:05:19 3 Tsegaye Kebede ETH 1 25 Apr 2010 4 2:05:20 Tsegaye Kebede 2 26 Apr 2009 5 2:05:24 Samuel Wanjiru 2 13 Apr 2008 6 2:05:27 4 Jaouad Gharib MAR 3 26 Apr 2009 7 2:05:30 5 Abderrahim Goumri MAR 3 13 Apr 2008 8 2:05:38 6 Khalid Khannouchi USA 1 14 Apr 20 02 9 2:05:48 7 Paul Tergat KEN 2 14 Apr 20 02 10 2:06:15 8 Emmanuel Mutai KEN 4 13 Apr 2008 11 2:06:17 9 Ryan Hall USA 5 13 Apr 2008 12 2:06:18 10 Evans Rutto KEN 1 18 Apr 20 04 13 2:06:23 Emmanuel Mutai 2 25 Apr 2010 14 2:06:35 11 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 3 14 Apr 20 02 15 2:06:36 12 Antonio Pinto POR 1 16 Apr 20 00 16 2:06:38 13 Deriba Merga ETH 6 13 Apr 2008 17 2:06:39 14 Felix Limo KEN 1 23 Apr 20 06 18 2:06:41 Martin Lel 2 23 Apr 20 06 19 2:06:48 15 Sammy Korir KEN 2 18 Apr 20 04 20 2:06:52 16 Abdelka der El Mouaziz MAR 4 14 Apr 20 02 21 2:06:53 Emmanuel Mutai 4 26 Apr 2009 22 2:06:55 17 Hendrick Ramaala RSA 3 23 Apr 20 06 23 2:06:55 Jaouad Gharib 3 25 Apr 2010 24 2:07:02 Jaouad Gharib 3 18 Apr 20 04 25 2:07:04 Khalid Khannouchi 4 23 Apr 20 06 26 2:07:06 18 Ian Syster RSA 5 14 Apr 20 02 27 2:07:11 Abdelkader El Mouaziz 1 22 Apr 20 01 28 2:07:22 19 Stefano Baldini ITA 5 23 Apr 20 06 29 2:07:26 Martin Lel KEN 1 17 Apr 20 05 30 2:07:29 Stefano Baldini 6 14 Apr 20 02 31 2:07:33 Abdelkader El Mouaziz 2 16 Apr 20 00 32 2:07:33 20 Abderrahime Bouramdane MAR 4 25 Apr 2010 33 -

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL of FAME MEMBERS

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL OF FAME MEMBERS 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Bob Cambell Ted Corbitt Tarzan Brown Pat Dengis Horace Ashenfleter Clarence DeMar Fred Faller Victor Drygall Leslie Pawson Don Lash Leonard Edelen Louis Gregory James Hinky Mel Porter Joseph McCluskey John J. Kelley John A. Kelley Henigan Charles Robbins H. Browning Ross Joseph Kleinerman Paul Jerry Nason Fred Wilt 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 R.E. Johnson Eino Pentti John Hayes Joe Henderson Ruth Anderson George Sheehan Greg Rice Bill Rodgers Ray Sears Nina Kuscsik Curtis Stone Frank Shorter Aldo Scandurra Gar Williams Thomas Osler William Steiner 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Hal Higdon William Agee Ed Benham Clive Davies Henley Gabeau Steve Prefontaine William “Billy” Mills Paul de Bruyn Jacqueline Hansen Gordon McKenzie Ken Young Roberta Gibb- Gabe Mirkin Joan Benoit Alex Ratelle Welch Samuelson John “Jock” Kathrine Switzer Semple Bob Schul Louis White Craig Virgin 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Nick Costes Bill Bowerman Garry Bjorklund Dick Beardsley Pat Porter Ron Daws Hugh Jascourt Cheryl Flanagan Herb Lorenz Max Truex Doris Brown Don Kardong Thomas Hicks Sy Mah Heritage Francie Larrieu Kenny Moore Smith 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Barry Brown Jeff Darman Jack Bacheler Julie Brown Ann Trason Lynn Jennings Jeff Galloway Norm Green Amby Burfoot George Young Fred Lebow Ted Haydon Mary Decker Slaney Marion Irvine 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ed Eyestone Kim Jones Benji Durden Gerry Lindgren Mark Curp Jerry Kokesh Jon Sinclair Doug Kurtis Tony Sandoval John Tuttle Pete Pfitzinger 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Miki Gorman Patti Lyons Dillon Bob Kempainen Helen Klein Keith Brantly Greg Meyer Herb Lindsay Cathy O’Brien Lisa Rainsberger Steve Spence 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Deena Kastor Jenny Spangler Beth Bonner Anne Marie Letko Libbie Hickman Meb Keflezighi Judi St.