The Battle of Whiteclay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metafora Konseptual Dalam Lukas Graham 3 the Purple Album: Analisis Semantik Kognitif

Volume 9, No. 2, September 2020 p–ISSN 2252-4657 DOI 10.22460/semantik.v9i2.p85-92 e–ISSN 2549-6506 METAFORA KONSEPTUAL DALAM LUKAS GRAHAM 3 THE PURPLE ALBUM: ANALISIS SEMANTIK KOGNITIF Afni Apriliyanti Devita 1, Tajudin Nur 2 1 Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung Sumedang KM.21, Hegarmanah, Kec. Jatinangor, Kabupaten Sumedang, Jawa Barat 45363 2 Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung Sumedang KM.21, Hegarmanah, Kec. Jatinangor, Kabupaten Sumedang, Jawa Barat 45363 1 [email protected] 2 [email protected] Received: December 19, 2019; Accepted: September 5, 2020 Abstract This study is a cognitive semantik analysis regarding the use of metaphors in song lyrics. The method used is the descriptive qualitative. Lukas Graham is a band from Denmark. The data were taken from 10 songs of Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album. The aims of this study are to discuss (1) metaphorical characteristics in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album, (2) metaphorical types in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album, and (3) image schemes contained in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album. The theory used are the conceptual metaphor of Lakoff and Johnson (2003) as the main theory and the image scheme of Croft & Cruse (2004). The result showed 21 data of conceptual metaphor with 15 ontological metaphors, 2 orientational metaphors, and 4 structural metaphors. The ontological metaphors is the most dominant in Lukas Graham 3 The Purple Album. The image scheme found in the study were 3 scheme containers, 3 scheme unities, 9 scheme existences, 4 scheme identities, and 2 scheme spaces. -

Policy Update Convention & Marketplace

National Congress of American Indians 2019 Annual Policy Update Convention & Marketplace Albuquerque, NM TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................... 1 Policy Overview ................................................................................................................................... 2 Agriculture and Nutrition.................................................................................................................... 3 Farm Bill ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Budget and Appropriations ................................................................................................................. 6 Census ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Economic and Workforce Development ........................................................................................... 13 Taxation and Finance ....................................................................................................................... 13 Tribal Labor Sovereignty Act ........................................................................................................... 17 Entrepreneurship and Economic Development.................................................................................. 18 Workforce -

Październik 09/2018

2zł Jesień niesie ze sobą ponury czas, świat za ok- nami traci swoje barwy, a nas dopada jesien- na chandra. Nauka i lekcje przychodzą nam z coraz więk- szą trudnością, ale w ten czas humor poprawi nowe wydanie Szkolnej Gazetki SQLPress. Zapraszamy do miłej lektury, obfitej w wiele ciekawych tematów. Redaktor naczelna Październik 09/2018 1 2 Absolwent Dietetyki SALON MATURZYSTY Absolwent Dietetyki ma bardzo szerokie możliwości poszukiwania Żywienie człowieka to jedna z dziedzin nauki, które przeżywają ostatnio zatrudnienia. Zwykle kieruje swoje pierwsze kroki do publicznych i prawdziwy renesans. Od kilkunastu lat ludzie zyskują coraz większą niepublicznych placówek ochrony zdrowia. Gdy zyska już doświad- świadomość żywieniową, dzięki ogólnemu rozwojowi branży spożywc- czenie zawodowe oraz osiągnie pierwsze sukcesy, otwiera własny zej. Wraz z systematycznym zwiększaniem oferty na rynku żywie- gabinet dietetyczny, w którym przyjmuje pacjentów i prowadzi kon- niowym, rosną budżety przeznaczane na marketing tej branży. Paradok- sultacje dietetyczne. W swojej pracy współdziała z lekarzami i tera- salnie - o wiele trudniej zrobić teraz zdrowe zakupy niż przed laty, kiedy lista produktów spożywczych w sklepach była bardzo uboga. Te wszys- peutami. tkie uwarunkowania sprawiają, że ludzie potrzebują fachowej pomocy i edukacji w dziedzinie dietetyki. Oto niektóre akademie w których możesz studiować dietetykę: Gdański Uniwersytet Medyczny Uniwersytet Medyczny im. K. Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu Uniwersytet Medyczny w Białymstoku Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu Kandydat na Dietetykę W zależności od wybranej uczelni, kandydaci przechodzą różne Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi procedury rekrutacyjne. Najczęściej spotykanym kryterium przyję- cia na te studia jest konkurs świadectw ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem biologii, chemii oraz języków obcych. Przedmioty te są fundamentem wiedzy przyszłych dietetyków, dlatego warto postarać się już w szkole średniej o dobre wyniki matury. -

THE CANDIDATES on the ISSUES on the BALLOT January 2020

Policy Pack III.I THE CANDIDATES ON THE ISSUES ON THE BALLOT January 2020 PLATFORMWOMEN.ORG @PLATFORMWOMEN YEAR IN REVIEW Table of Contents Note from the Team 1 Meet The Candidates 2 Reparations 3 College Access 7 Healthcare 13 Disability 18 Indigenous Rights 24 Sexual Violence Prevention 31 Gun Violence Prevention 36 LGBTQ+ Equity 45 Reproductive Rights 52 Environmental Racism 57 Justice Reform 63 Workplace and Economic Opportunity 70 D.C. Statehood 77 THE CANDIDATES Note from the Team There have been remarkable leaps and bounds of young people reclaiming our government. We are voting in higher numbers and regularly taking to the streets to strike and to protest. Yet still far too many of us believe our votes do not matter. And we get it. We know that this belief is not rooted in apathy but rather from a very deep reality that inside city halls, state capitals, and the chambers of Congress, elected officials make decisions about our bodies, lives, and futures without listening to our voices. It is rooted in the reality that on the campaign trail, we are promised change that counts everybody in, but in session, we are dealt legislation that negotiates people out. We can change this. We have to change this. We do that through voting AND through the actions we take every day before, on, and after election day. It is the work we do before election day that ensures campaign promises reflect us and the future we are determined to create. It is the voting we do on election day that ensures we fill the seats of power with partners in progress. -

SENATOR KARPISEK: Okay, I Think We're Going to Get Started

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Rough Draft General Affairs Committee and Judiciary Committee September 25, 2009 [LR199] SENATOR KARPISEK: Okay, I think we're going to get started. If everybody can find a seat, figure everything out. Okay. Number one, it says, promptly begin at 1:30. So we haven't done that, but that's all right. I would like to say right away that I hope to be out of here by 5:00. We are not going to use the light system today so everyone has time to say what they want to say. I would ask that you not repeat anymore than you have to. Hearing the same thing over and over gets old for everyone. However, we want to give everyone a chance to voice an opinion, share ideas if they'd like to. So be as brief as you can and I will start off with just some of the housekeeping things. This is an interim study for LR199. And it is a joint hearing between the General Affairs Committee and the Judiciary Committee. My name is Senator Russ Karpisek of Wilber and I am the chair of the General Affairs Committee and I will be chairing today's hearing. General Affairs Committee members who are here today are Senator Coash of Lincoln who is also on the Judiciary Committee; Senator Price of Bellevue who I didn't recognize today because he has hair; (laugh) he was bald all session, seriously; Senator Dierks of Ewing. Judiciary members who are present are chairman Senator Ashford of Omaha; Senator Lathrop of Omaha; Senator McGill of Lincoln; and Senator Lautenbaugh of Omaha. -

Ingham County News $1.00

••• —v^>'•^;^ie-•;^•>••ri:^.s;5^ . Tanto, tlie murderer of the family NOTHING OOINQ ON. Clothing.—L. C. Webb. Legal. at Delhi, wascaptured near the village kawirram Dry Fork Contributed t« m of OkemoB Monday evening, and Arkantaw Coontjr Vapor. NNUAL STATEMENT FOB THE YEAR ondlns December 31sl, A. 0.1888. of the would have been lynched only for the Rain. Acondition and aflalra ot tho Farmers'Mutual Biver rising. Fire Insurance Company, located at Mason, interference of tbeoffloera. 1-4 Off! 1-4 0ff!kp™ orEaniied under the laws of the State of Mich People are clearing up new ground, igan, and doing business In: the County of The chlldrens' concert, which was Ingham In said State. „ ., . Ihdefluately postponed in consequence kggs are scarce, but prospects are RICHARD J. BCLLKK, President. good. ORVit.t.K F. MtLi.ER, Secretary. CLUB ROOM, Jan. 28,1889. of the sickness of Mrs. Sturgi# daugh Postofflce Address of Secretary, Mason. Dan Boyd chopped off three of his TEN THOUSAND DOLLAR pi. Tber^ was a good attendance and ter, will be Riven at the M. E. church XEMBEr.8HIF8. ,ii V some new faces for this year. on Wednesday evening, Feb. 6. A toes with an axe day before yesterday. CASH SALE OF Number of members December 3lst, of prevtouH years 2,583 VOL. XXXI-NO. 6. • Secretary Ives absent. good program is expected, admission Uncle Billy Marsh has the thanks of Number of members added during MASON, MICH.. THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 7.1889. I Under the call "Market Reports," ten cents. The proceeds are to be the ye correspondent for a mess of squir^ the present year WHOLE NO. -

Volume 46, Number 12: November 05, 2008 University of North Dakota

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special University Letter Archive Collections 11-5-2008 Volume 46, Number 12: November 05, 2008 University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/u-letter Recommended Citation University of North Dakota, "Volume 46, Number 12: November 05, 2008" (2008). University Letter Archive. 70. https://commons.und.edu/u-letter/70 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Letter Archive by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of North Dakota | University Letter Main Navigation SEARCH UND Print this Issue ISSUE: Volume 46, Number 12: November 05, 2008 A to Z Index Map Contents ABOUT U LETTER Top Stories University Letter is published electronically weekly on President Kelley will give State of the University address Nov. 18 Tuesday afternoons. Submissions are due at 10 UND AgCam set for Nov. 14 trip to International Space Station a.m. Tuesday. Events to Note U LETTER U Letter Home Astronomy public talk is Nov. 5 Submit a Story Frank White to speak at Leadership Series Women's Center talk will focus on Women's Health Week Register now for 'Stone Soup' awards program Instructional Development holds seminars on grant proposals National Nontraditional Student Recognition Week is this week Doctoral examination set for Cynthia Lofton "Big Questions, Worthy Dreams" author to visit campus Nov. -

Iowa Problem Zine.Pub

9. Donnelle Eller. Iowa could support 45,700 livestock confinements, but should it? Des Moines Register, March 2018. www.desmoinesregister.com-story-money- Iowa - Big-Ag’s Sacrifice Zone: agriculture-2018-0.-08-iowa-can-support-12-300-cafos-but- should-.21110002- Accessed June 10, 2018 An Indigenous Perspective 10. 5rian 5ienkowski. My Number One Concern is Water”: As Hog Farms Grow in Size A Land Decoloni%aon Project 'ine Series by Seeding Sovereignty and Number, so do Iowa Water Problems. Environmental 6ealth News, November 2012. www.ehn.org-water-polluon-hog-farming-23011778.1.html Accessed June 10, 2018 11. Carolyn Ra8ensperger. Personal Correspondence. Summer 2012 12. Pes.cide. 6ow Products are Made. www.madehow.com-9olume-1-Pescide.html:ix%%3Rg9g nGK Accessed September 21, 2018 1.. Lance oster. ,ersonal Correspondence. Summer 2018 . 11. John Doershuk. ,rotec.ng Something Sacred. Iowa Natural 6eritage oundaon, March 2018. www.inhf.org-blog-blog-protecng-something-sacred- Accessed June 10, 2018 We are a multi-generational led model by and for Indigenous and Non- Indigenous womxn based on mentoring relationships and principles of unity, solidarity, justice, sharing and respect. A Seeding Sovereignty Publicaon, 2018 Created by Chrisne Nobiss Art by Jackie awn Seedingsovereignty.org those tribes don’t live here anymore, but sll feel that this is their historical homeland and During this me of climate crisis, it is imperave that we transform the coloni%ed that the features found here are an acve part of their culture today.”11 Ahese naons mind of seFler descendant society by pushing Indigenous ideologies onto the world have been involved in more than just archeological protecon--many have helped stage. -

Andreas Gus Hansen CV

CV Andreas Gus Hansen Senast uppdaterad 2021-04-29 09:18 Personal data Age 33 Andreas G. Hansen CV Education Year School Education 2011 Nørgaards Højskole Film Acting 2011-2012 New York Film Academy Acting For Film & TV Stage Year Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director 2019 Idomeneo, Royal Danish Soldier Det Kongelige Teater Robert Carsen Opera Film/TV Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director Mistake (short film) Lars (supporting) Two Trick Pony Joe Withers Blot et Bånd (short film) Big Brother (lead) NEXT Marianna Bjørgheim The Investigation (TV series) Andreas (guest) Miso Film Tobias Lindholm The Sommerdahl Murders (TV Carl / P:H:A Assistent (guest) Sequoia Carsten Myllerup series) Shit Happens (short film) Lead Jesper Holm Pedersen KBH Film- og Fotoskole Dreaming in Mono (mini series) 'Mad' Mads Steen (supporting) Happy Fiction Jens Jonsson Sida 1/3 Ronnie Looks at the Stars Brian Odense Filmværksted Jesper Quistgaard (novel film) Video/Music video Production Artist Song Role New Land Lukas Graham Not A Damn Thing Changed Friend Karma Film Tina Dickow Fancy Hero David Fincher Justin Timerlake ft Jay-Z Suit and Tie Guy in casino Radical Media P!NK Blow Me (one last kiss) Hero Team Karate Dúné Victim Of The City Guy Commercial Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director Lego Adult LEGO Rasmus Mateus Collection Friend in group Belckout Josefin Malmén VVS Branchen VVS'er Entrance Film Tobias Kampmann Arla Jörd Hero Provocateur Meeto Kronborg Cocio Friend Hobby Film Martin Åkerhage Volvo Grandson Smuggler / Gatehouse Miles Jay NCAA Student Chelsea Productions Nadav Kander Spar Købmand Friend to Hero Another CPH Martin Høgsted Norwegian Airlines Traveling passenger Bacon Productions Miracle Whip Hero Parachute Productions Dan Monick Other Year Production Position Prod. -

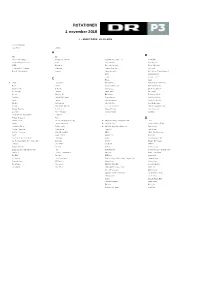

Rotation Master P3.Xlsx

ROTATIONER 1. november 2018 = ADDET SIDEN 24-10-2018 P3s Uundgåelige Jade Bird Uh Huh A B MØ Blur Phlake, Mercedes Waited All Summer Post Malone, Swae Lee Sunflower Troye Sivan, Charli XCX 1999 Zara Larsson Ruin My Life KOPS Salvation Dermot Kennedy Power Over Me 5 Seconds Of Summer Valentine Twenty One Pilots My Blood Bastille, Marshmello Happier Lukas Graham Not a Damn Thing Changed Benal Lampeskærm C Sigrid Sucker Punch Elisha Loyal Robyn Ever Again Karl William Høje strå (Dunhammer) Bette Darling Nephew, Nik & Jay Rejsekammerater Dominic Fike 3 Nights Alex Vargas Silent Treatment Nicklas Sahl Planets Dean Lewis Be Alright Halsey Without Me Barselona Fra Wien til Rom Ava Max Sweet But Psycho Grace Carter Why Her Not Me Khalid Better Elias Boussnina Candy [Radio Edit] Medina Væk mig nu Alice Merton Why So Serious Nosaint Nocturnal Delirium Silk City, Dua Lipa Electricity [Radio Edit] Maggie Rogers Give a Little Lukas Graham Love Someone L Devine Peer Pressure Ariana Grande breathin Christine And The Queens 5 dollars Thøger Dixgaard Pæn D Selma Judith Kind of Lonely [Radio Edit] Kendrick Lamar, Anderson .Paak Tints Jungle Heavy, California Little Dragon Lover Chanting [Edit] Alexander Oscar Coffee Table Ellie Goulding, Diplo, Swae Lee Close to Me Scarlet Pleasure Superpower Freja Kirk Fine Things Artifact Collective Ways [Radio Edit] HRVY I Wish You Were Here Yulez Major Friend Kwamie Liv New Boo Calvin Harris, Sam Smith Promises Aisle Favorite Bad Habit Au/Ra, Alan Walker, Tomine Harket Darkside IVYxM Slippin' On Trouble Jamaika Abu Debe RoseGold Selena Imagine Dragons Natural Askling So Precious Bugzy Malone, Rag'n'Bone Man Run Communions Is This How Love Should Feel? The 1975 Love It If We Made It NAO, SiR Make It Out Alive Ray BLK Run Run ROSALÍA Malamente St. -

Building Momentum for the Future of Tribal Nations

LEGACY IN MOTION BUILDING MOMENTUM FOR THE FUTURE OF TRIBAL NATIONS TO PROTECT, SECURE, PROMOTE, AND IMPROVE THE LIVES OF AMERICAN INDIAN AND ALASKA NATIVE ANNUAL REPORTANNUAL PEOPLE AND THEIR COMMUNITIES 2018-2019 A message from the president Dear Tribal Leaders, NCAI Members, Native Peoples, and Friends of Indian Country, On behalf of the National Congress of American Indians, welcome to NCAI’s 76th Annual Convention! We come together this week to advance the hallowed charge of NCAI’s founders, who assembled in Denver 75 years ago to create a single, national organization to collectively protect and strengthen tribal sovereignty for the benefit of our future tribal generations. We gather this week to carry on our work of empowering our tribal governments, communities, and citizens, to provide them the ability and tools to create brighter futures of their own design. It takes all of us, working together, to make that happen. It takes all of us, working together, to hold the federal government accountable to its trust and treaty obligations to our tribal nations. This past year has shown us that no matter the challenges we face as Indian Country, as nations within a nation, we are strong, we are resilient. Even in the midst of a government shutdown, tribal nations rallied together to forge historic policy achievements that enhance tribal self-determination and self-governance. We joined forces with our partners and Watch Jefferson Keel’s Together allies to accomplish lasting victories that transcend political parties or this particular As One message Administration and Congress. We continued to lay a firmer foundation for transformative, positive changes across our tribal lands and communities. -

Paseo Post Intercambios Paseo

F E B R E R O 2 0 1 9 | N º 2 PASEO POST INTERCAMBIOS PASEO PRIMARIA SE ESTRENA EN PASEOPOST LA EDUCACIÓN NO ES CAPACITAR PERSONAS PARA LA EMPRESA , SINO FORMAR PERSONAS Foto de :http://audioforo.com/2017/10/08/la-educacion-en-espana/ Foto de: https://conscientemente.net/escribir-hace-bien-la-escritura-como-practica-meditativa-y-terapeutica/ E N S A L E S I A N O S P A S E O INTERCAMBIOS PASEO A r i a d n a C a l v o e I r e n e C i s n e r o s | E d i t a d o p o r : Carmen Silva Al comienzo de este curso, alumnos de tercero y cuarto de la E.S.O, y también primero y segundo de bachillerato, tuvieron la oportunidad de experimentar un intercambio escolar con alumnos extranjeros. Los alumnos de tercero, viajaron hasta un colegio situado en Ruan, una ciudad del noroeste de Francia. Meses después, alumnos franceses asistieron a nuestro colegio durante unos días. Todos coinciden en que fue una gran experiencia y la volverían a repetir. Los alumnos de bachillerato estuvieron en un colegio de Boston. Boston, es la capital del Estado de Massachusetts, y una de las ciudades más antiguas de los Estados Unidos.Las familias de estos alumnos, acogieron después a los estudiantes norteamericanos, para completar el intercambio. Un colegio de Dublín, próximo al mar, ha sido el destino de los estudiantes de cuarto de la E.S.O. ''Para mí, el intercambio con Irlanda ha sido una manera de aprender otra cultura y conocer cómo es estudiar en ese país, ya que cuando vas de turismo es algo que no sueles ver.