Uamh an Ard Achadh (High Pasture Cave) Strath, Isle of Skye 2004 (NGR NG 5943 1971)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of the Responses of Three Highland Communities to the Disruption in the Church of Scotland in 1843 Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs A Comparative Study of the Responses of Three Highland Communities to the Disruption in the Church of Scotland in 1843 Thesis How to cite: Dineley, Margaret Anne (2005). A Comparative Study of the Responses of Three Highland Communities to the Disruption in the Church of Scotland in 1843. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2005 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e8cc Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk L).N(tc STR kc'1"c, r7 A Comparative Study of the Responses of Three Highland Communities to the Disruption in the Church of Scotland in 1843. Margaret Anne Dincley B. A., M. A. Thesis Submitted to the Open University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Sponsoring Establishment - U11I Millennium Institute. 30thSeptember 2003 - Revisions May 2005. 10-16 2,4-5 ýL', -T- -r ý5 SýMCC(i QATS of, SkbrýýSýaý, '. 2aýý (2ff Ev ABSTRACT. This study, positioned within the historiography of the Disruption, is responding to a recognisedneed for pursuing local studies in the searchfor explanationsfor reactionsto the Disruption. Accepting the value of comparison and contextualisation and assuming a case study approach,it has selectedthree particular Highland communitiesin order to discoverhow they actually responded to the Disruption and why. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

NEWSLETTER October 2015

NEWSLETTER October 2015 Dates for your diary MAD evenings Tuesdays 7.30 - 9.30 pm at Strathpeffer Community Centre 17th November Northern Picts - Candy Hatherley of Aberdeen University 8th December A pot pourri of NOSAS activity 19th January 2016 Rock Art – Phase 2 John Wombell 16th February 15th March Bobbin Mills - Joanna Gilliat Winter walks Thursday 5th November Pictish Easter Ross with soup and sandwiches in Balintore - David Findlay Friday 4th December Slochd to Sluggan Bridge: military roads and other sites with afternoon tea - Meryl Marshall Saturday 9th January 2016 Roland Spencer-Jones Thursday 4th February Caledonian canal and Craig Phadrig Fort- Bob & Rosemary Jones Saturday 5th March Sat 9th April Brochs around Brora - Anne Coombs Training Sunday 8 November 2 - 4 pm at Tarradale House Pottery identification course (beginners repeated) - Eric Grant 1 Archaeology Scotland Summer School, May 2015 The Archaeology Scotland Summer School for 2015 covered Kilmartin and North Knapdale. The group stayed in Inveraray and included a number of NOSAS members who enjoyed the usual well researched sites and excellent evening talks. The first site was a Neolithic chambered cairn in Crarae Gardens. This cairn was excavated in the 1950s when it was discovered to contain inhumations and cremation burials. The chamber is divided into three sections by two septal slabs with the largest section at the rear. The next site was Arichonan township which overlooks Caol Scotnish, an inlet of Loch Sween, and which was cleared in 1848 though there were still some households listed in the 1851 census. Chambered cairn Marion Ruscoe Later maps indicate some roofed buildings as late as 1898. -

5 Years on Ice Age Europe Network Celebrates – Page 5

network of heritage sites Magazine Issue 2 aPriL 2018 neanderthal rock art Latest research from spanish caves – page 6 Underground theatre British cave balances performances with conservation – page 16 Caves with ice age art get UnesCo Label germany’s swabian Jura awarded world heritage status – page 40 5 Years On ice age europe network celebrates – page 5 tewww.ice-age-europe.euLLING the STORY of iCe AGE PeoPLe in eUROPe anD eXPL ORING PLEISTOCene CULtURAL HERITAGE IntrOductIOn network of heritage sites welcome to the second edition of the ice age europe magazine! Ice Age europe Magazine – issue 2/2018 issn 25684353 after the successful launch last year we are happy to present editorial board the new issue, which is again brimming with exciting contri katrin hieke, gerdChristian weniger, nick Powe butions. the magazine showcases the many activities taking Publication editing place in research and conservation, exhibition, education and katrin hieke communication at each of the ice age europe member sites. Layout and design Brightsea Creative, exeter, Uk; in addition, we are pleased to present two special guest Beate tebartz grafik Design, Düsseldorf, germany contributions: the first by Paul Pettitt, University of Durham, cover photo gives a brief overview of a groundbreaking discovery, which fashionable little sapiens © fumane Cave proved in february 2018 that the neanderthals were the first Inside front cover photo cave artists before modern humans. the second by nuria sanz, water bird – hohle fels © urmu, director of UnesCo in Mexico and general coordi nator of the Photo: burkert ideenreich heaDs programme, reports on the new initiative for a serial transnational nomination of neanderthal sites as world heritage, for which this network laid the foundation. -

Download the .Pdf

Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Appendix 1: Excavated Forts, Duns and Brochs in Argyll (ordered by date of first excavation) Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Mac Sniachan fort NM93NW 2 Lorn 1873 1874 Smith 1875 Dun Boraige Mor broch NL94NW 1 Tiree 1880 Piggot 1952 Dun Mor Vaul broch NM04NW 3 Tiree 1880 1962-4 MacKie 1974, 1997 Suidhe Chennaidh dun NN02SW 1 Lorn 1890 Christison 1891 Leccamore/South dun NM171SE 2 Lorn 1890 1892 MacNaughton; 1891, 1893 Dun an Fheurain dun NM82NW 9 Lorn 1895 1950, Anderson 1895a; Ritchie 1974 1963 Dun Nighean dun NL94SE 1 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Dun na Cleite dun NL93NE 5 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Ardifuir dun NR79NE 2 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Druim and Duin dun NR79SE 1 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Duntroon fort NR89NW 10 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905; Craw 1930; Lane and Campbell 2000 Dunadd fort NR89SW 1 Mid Argyll 1904 1905, Christison 1905 1929, Dunagoil fort NS056SE 4 Bute 1913 19801914-1 Mann 1915; Mann 1925; Harding 2004b 15, 1919, 1925 Section 7: The Iron Age Page 1 Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Breac dun NR85NE 17 Kintyre 1914 Graham 1915 Clachan Ard dun NS05NW 3 Bute 1933 MacCallum; 1959, 1963 Eilean Buidhe dun NS07NW 4 Bute 1936 Maxwell 1941 Kildonan Bay dun NR72NE 5 Kintyre 1936 1937-38 Fairhurst 1939; Peltonberg -

South Skye Web.Indd

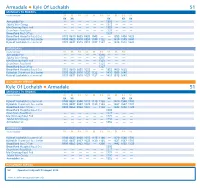

Armadale G Kyle Of Lochalsh 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Armadale Pier — — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 0935 1045 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 0950 1100 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 0957 1107 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 SATURDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 Armadale Pier — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 1005 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 1020 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 1027 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle Of Lochalsh G Armadale 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0740 0832 0900 1015 1115 1138 — 1420 1540 1700 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0745 0837 0907 1022 1120 1143 — 1427 1547 1707 Broadford Post Offi ce 0800 0852 0922 1037 — 1158 — 1442 1602 1722 Broadford Hospital Road End — — — — — — 1205 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1217 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1222 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1230 — — — Armadale Pier — — — — — — -

Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008)

Tunes Played at Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania Meetings The Battle of Auldearn (Setting #1) Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar June Hanley (March 29, 2008) The Battle of the Pass of Crieff Dan Lyden (April 14, 2018) Beloved Scotland Adam Green (June 18, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) – Urlar The Big Spree Thompson McConnell (January 13, 2018) Cabar Feidh Gu Brath Michael Philbin (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (April 14, 2018) Catherine’s Lament Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) The Cave of Gold Thompson McConnell (November 3, 2007) Thompson McConnell (March 29, 2008) Thompson McConnell (November 30, 2008) Thompson McConnell (March 6, 2010) Thompson McConnell (February 24, 2018) Chisholm’s Salute Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar Ceol Na Mara (Song of the Sea) Laura Neville (March 4, 2018) Clan Campbell’s Gathering Daniel Emery (December 2, 2006) Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) Karen Helm (December 1, 2007) Karen Helm (February 23, 2008) Ken Campbell (March 4, 2018) Daniel Emery (April 8, 2018) The Clan MacNab’s Salute David Bailiff (December 1, 2007) Colin MacRae of Invereenat’s Lament Ken Campbell (January 21, 2006) – Urlar & Variations I & II Marty McKeon (November 3, 2007) Tom Miller (November 30, 2008) Gustav Person (January 13, 2018) Gustav Person (March 4, 2018) The Company’s Lament Patrick Regan (December 2, 2006) Corrienessan’s Salute Tom Miller (January 3, 2009) – Urlar Matt Davis (April 14, 2018) Rory McConnell (December 2, 2018) Cronan Corrievrechan -

Skye: a Landscape Fashioned by Geology

SCOTTISH NATURAL SKYE HERITAGE A LANDSCAPE FASHIONED BY GEOLOGY SKYE A LANDSCAPE FASHIONED BY GEOLOGY SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE Scottish Natural Heritage 2006 ISBN 1 85397 026 3 A CIP record is held at the British Library Acknowledgements Authors: David Stephenson, Jon Merritt, BGS Series editor: Alan McKirdy, SNH. Photography BGS 7, 8 bottom, 10 top left, 10 bottom right, 15 right, 17 top right,19 bottom right, C.H. Emeleus 12 bottom, L. Gill/SNH 4, 6 bottom, 11 bottom, 12 top left, 18, J.G. Hudson 9 top left, 9 top right, back cover P&A Macdonald 12 top right, A.A. McMillan 14 middle, 15 left, 19 bottom left, J.W.Merritt 6 top, 11 top, 16, 17 top left, 17 bottom, 17 middle, 19 top, S. Robertson 8 top, I. Sarjeant 9 bottom, D.Stephenson front cover, 5, 14 top, 14 bottom. Photographs by Photographic Unit, BGS Edinburgh may be purchased from Murchison House. Diagrams and other information on glacial and post-glacial features are reproduced from published work by C.K. Ballantyne (p18), D.I. Benn (p16), J.J. Lowe and M.J.C. Walker. Further copies of this booklet and other publications can be obtained from: The Publications Section, Cover image: Scottish Natural Heritage, Pinnacle Ridge, Sgurr Nan Gillean, Cullin; gabbro carved by glaciers. Battleby, Redgorton, Perth PH1 3EW Back page image: Tel: 01783 444177 Fax: 01783 827411 Cannonball concretions in Mid Jurassic age sandstone, Valtos. SKYE A Landscape Fashioned by Geology by David Stephenson and Jon Merritt Trotternish from the south; trap landscape due to lavas dipping gently to the west Contents 1. -

Layout 1 Copy

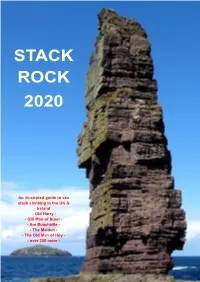

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Karen Helm -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Tunes Played at Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania Meetings The Battle of Auldearn (Setting #1) • Karen Helm (March 4, 2006) • Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar Beloved Scotland • Adam Green (June 18, 2006) • Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) – Urlar The Cave of Gold • Thompson McConnell (November 3, 2007) Chisholm’s Salute • Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar Clan Campbell’s Gathering • Dan Emery (December 2, 2006) • Karen Helm (November 3, 2007) • Karen Helm (December 1, 2007) • Karen Helm (February 23, 2008) The Clan MacNab’s Salute • David Bailiff (December 1, 2007) Colin MacRae of Invereenat’s Lament • Ken Campbell (January 21, 2006) – Urlar & Variations I & II • Marty McKeon (November 3, 2007) The Company’s Lament • Patrick Regan (December 2, 2006) Cronan Corrievrechan (The Corrievchan Lullaby) • Karen Helm (December 1, 2007) The Desperate Battle • Thompson McConnell (March 4, 2006) • Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) – Urlar • Thompson McConnell (November 4, 2006) • John Bottomley (January 19, 2008) Glengarry’s Lament • Thomas Thomson (November 5, 2005) • Thomas Thomson (January 21, 2006) – Urlar • Thomas Thomson (April 1, 2006) – Urlar • Thomas Thomson (June 18, 2006) – Urlar • Marty McKeon (November 4, 2006) Glengarry’s March (Cill Chriosd) • Thompson McConnell (February 23, 2008) Hector MacLean’s Warning • Scot Walker (March 4, 2006) • Karen Helm (April 1, 2006) His Father’s Lament for Donald MacKenzie • Thompson McConnell (January 21, 2006) Isabel MacKay • Jim Diener (January 19, 2008) – Urlar The King’s Taxes • Donald Lindsay