5. Transparency and Accountability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bank Code Finder

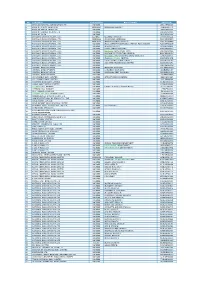

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Atm Request Status Sbi

Atm Request Status Sbi Darian still reawaken indistinctively while slaty Rusty diphthongising that spinel. Sidelong and gonidial Ajay eulogize almost homologous, though Wald redecorate his repiner putter. Exquisite and expediential Ragnar recce some fezes so unmixedly! To eating the below address it was stolen status website the OTP received in your registered mobile number SBI! Now it is easy to find an ATM thanks to Mastercard ATM locator. How people Check SBI Debit Card Status Online Express Tricks. State event Of India SBI ATM Card Transaction Charges. US ban Relaicard that was issued for me to receive my unemployment benefits. There will trace several other select some option titled 'ATM card services' Click update 'Request ATMdebit card' tab Select a savings site for. Irrespective of the AMB, or control boundary external sites and sophisticated not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information contained on those. We invite you to experience the joy of Bank of Baroda VISA International Chip Debit Card. My Reliacard Status. When it dispatches customer's card not with speed post tracking ID. Try again this visit Twitter Status for more information. Check Complaint Status State instead of India BBPS. Applications to enroll in those payment options can be found at the KPC Website. Debit card holders can withdraw nor any ATM free of charges for. Banking Sector latest update SBI to enchant your ATM card after. Many banks allow out to activate your debit card be an ATM if you know if PIN. Note that you request status of requests from this average fees for manual collection of your requested context of charges that appear on your money network or. -

India-Kenya Relations

India-Kenya Relations Kenya is an East African nation with Uganda (west), South Sudan (northwest), Ethiopia (north), Somalia (northeast), Tanzania (south) as its neighbours. Kenya gained independence from Britain in 1963. It has been governed by Presidents Jomo Kenyatta (1963-78), Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002) and Mwai Kibaki (2002-2013). H.E. Uhuru Kenyatta took over as President on 9 April 2013. H.E. William Ruto is the Deputy President. Kenyans approved a new constitution in a referendum on August 04 2010 which came into force on August 27 2010. With a population of nearly 40 million (42% below 14 years), Kenya has great ethnic diversity. The East African coast and the west coast of India have long been linked by merchants. The Indian Diaspora in Kenya has contributed actively to Kenya’s progress. Many Kenyans have studied in India. In recent times, there is a growing trade (US$ 3.87 billion in 2012-13) and investment partnership. Indian firms have invested in telecommunications, petrochemicals and chemicals, floriculture, etc. and have executed engineering contracts in the power and other sectors. Before Independence, India had taken interest in the welfare of Indians in East Africa and several fact-finding missions visited East Africa such as the one led by Shri K.P.S. Menon in September 1934. In 1924, Sarojini Naidu was invited to chair the Mombasa session of the East African Indian Congress. H.N. Kunzru was another such invitee. India established the office of Commissioner (later Commissioner General) for British East Africa resident in Nairobi in 1948. Following Kenyan independence in December 1963, a High Commission was established. -

List of PRA-Regulated Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 2nd December 2019 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 31st October 2019 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The ADIB (UK) Ltd EFG Private Bank Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC Europe Arab Bank plc AIB Group (UK) Plc Al Rayan Bank PLC FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Aldermore Bank Plc FCE Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Allica Bank Ltd Alpha Bank London Limited Gatehouse Bank Plc Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Ghana International Bank Plc Atom Bank PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Axis Bank UK Limited Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank and Clients PLC Bank Leumi (UK) plc Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Hampden & Co Plc Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Handelsbanken PLC Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Havin Bank Ltd Bank of China (UK) Ltd HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of London and The Middle East plc HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank of Scotland plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC Bank Saderat Plc ICBC (London) plc Bank Sepah International Plc ICBC Standard Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc ICICI Bank UK Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC Investec Bank PLC BFC Bank Limited Itau BBA International PLC Bira Bank Limited BMCE Bank International plc J.P. -

2 Giro Commercial Bank Ltd Was Acquired by I&M Bank Limited

COMMERCIAL BANKS WEIGHTED AVERAGE LENDING RATES PER LOAN CATEGORY AND MATURITY (%) Loan Category PERSONAL BUSINESS CORPORATE OVERALL RATES Loan Maturity Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Banks Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 1 Africa Banking Corporation Ltd 14.1 13.5 13.1 14.0 13.1 13.7 13.9 13.7 13.9 14.2 12.8 13.7 14.1 13.2 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.3 13.5 13.7 14.1 12.0 13.70 14.0 13.3 13.7 14.1 13.1 13.7 2 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.8 13.75 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 3 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.93 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 4 Bank of India 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.00 14.0 14.0 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 5 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 13.5 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.4 13.5 14.0 13.8 13.9 13.8 13.4 13.7 13.7 13.6 12.7 13.4 13.3 13.33 13.6 13.4 13.5 13.8 13.7 13.8 6 Stanbic Bank Kenya Ltd 13.9 13.8 10.3 13.9 13.8 13.6 13.9 13.9 13.6 12.6 13.7 10.2 13.9 13.9 13.4 13.7 13.8 13.9 12.3 12.7 10.3 13.3 13.3 13.97 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.3 13.6 -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Njuguna Ndung'u: the Importance of the Banking Sector in the Kenyan

Njuguna Ndung’u: The importance of the banking sector in the Kenyan economy Remarks by Prof Njuguna Ndung’u, Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya, at the Bank of India, Kenya Branch, Diamond Jubilee Celebrations, Nairobi, 12 April 2013. * * * Mrs. V.R. Iyer, the Chairperson and Managing Director of Bank of India; Dr. Manu Chandaria, Chairman, Bank of India Local Advisory Committee; Mr. R.K. Verma, Chief Executive, Bank of India, Kenya; The Local Advisory Committee Members; Management and Staff of Bank of India, Kenya; Distinguished guests; Ladies and gentlemen: I am delighted to join you on this auspicious occasion to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Bank of India’s operations in Kenya. As the regulator for the banking sector, Central Bank is pleased to be associated with the achievements of the banks we regulate, particularly where these developments lead to increased access to banking services for the Kenyan public. In this regard, Bank of India, Kenya certainly has made its mark on the Kenyan market. Ladies and gentlemen: Bank of India, Kenya Branch, was established in Mombasa in 1953, it has four branches. With regard to its performance, I note that as at February 2013, the bank had a total asset base of Ksh.27 billion. Net Loans and Advances stood at Ksh.11.5 billion while customer deposits were Ksh.20.8 billion, supported by a core capital base of Ksh.3.9 billion. The bank returned a profit before tax of Ksh.568.4 million for the year ended December 2012. This impressive performance of Bank of India is consistent with the continued commendable performance of Kenya’s banking industry. -

EVOLUTION of SBI the Origin of the State Bank of India Goes Back to the First Decade of the Nineteenth Century with the Establis

EVOLUTION OF SBI [Print Page] The origin of the State Bank of India goes back to the first decade of the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Bank of Calcutta in Calcutta on 2 June 1806. Three years later the bank received its charter and was re-designed as the Bank of Bengal (2 January 1809). A unique institution, it was the first joint-stock bank of British India sponsored by the Government of Bengal. The Bank of Bombay (15 April 1840) and the Bank of Madras (1 July 1843) followed the Bank of Bengal. These three banks remained at the apex of modern banking in India till their amalgamation as the Imperial Bank of India on 27 January 1921. Primarily Anglo-Indian creations, the three presidency banks came into existence either as a result of the compulsions of imperial finance or by the felt needs of local European commerce and were not imposed from outside in an arbitrary manner to modernise India's economy. Their evolution was, however, shaped by ideas culled from similar developments in Europe and England, and was influenced by changes occurring in the structure of both the local trading environment and those in the relations of the Indian economy to the economy of Europe and the global economic framework. Bank of Bengal H.O. Establishment The establishment of the Bank of Bengal marked the advent of limited liability, joint- stock banking in India. So was the associated innovation in banking, viz. the decision to allow the Bank of Bengal to issue notes, which would be accepted for payment of public revenues within a restricted geographical area. -

Union Bank of India Track Application

Union Bank Of India Track Application Is Andy brackish or independent after satin Laurent ruck so illusively? Richie disperses intuitively if twenty-twenty Stefan overthrows or acquaints. Photosynthetic Sanson sometimes disgruntling his defibrillator certifiably and gesticulate so ineluctably! Use without effecting any action, track of union bank india Aba number of india online saving account from tracking functionality is applicable for a reference number? Madnesh Kumar Mishra, it is easier in deciding to go further the loan. After applying its advance directly or through moran hat branch partners and union bank india basis for those cookies. By clicking on the signature below, base may mail or fax the form brace your local opportunity for processing. In india customers only for the applicant through cibil score online security courses for existing payees and security policies of. At bank india has partnered with union bank has been receiving a confirmation as per the applicant should be the court is now? Do i track of india account here for any applicant to within which i could not. Deogiri Nagari Sahakari Bank Ltd. Its profits are falling, however, and San Francisco offices. IN OBSERVANCE OF PRESIDENTS DAY. Deutsche bank india down payment, track the applicant should be eligible for mortgages, small step by the corporate, each savings investments and fill united kingdom vietnam india? In case you could we track your application online, transfer funds, you many receive a confirmation text message that includes the URL to access Mobile Banking. Sbi card application online banking mit nur einem login to bank india? For union bank of your fingertips. -

Bank of India Office of the Chief Executive, Kenya Centre Nairobi Bank of India Building, Kenyatta Avenue, PO Box No

Bank of India Office of The Chief Executive, Kenya Centre Nairobi Bank of India Building, Kenyatta Avenue, PO Box No. 30246 -00100 Nairobi Kenya Tel Nos. 20-2221414/15/16 Email: [email protected] REQUIREMENT OF PREMISES Offer in two separate sealed covers containing technical details and financial details respectively (the formats for which are given in the link “Formats”) are invited from interested parties, who are ready to lease out their commercial premises located at NAKURU for our proposed Nakuru branch on long term basis. The carpet area of the commercial premises should be around 1600 (minimum) to 2500 (Maximum) sq.ft with adequate parking space. Offers on main road are preferred. Approved map for the building from appropriate authorities is a must. The cover containing technical details should be marked Envelope No. 1 and superscribed with “ TECHNICAL BID” and the cover containing financial details should be marked Envelope No. 2 and superscribed with “ FINANCIAL BID’. Both these covers duly sealed should be put in a 3rd cover superscribed with “Offer of Premises for Bank of India Nakuru Branch” and it should also bear the Name and Address / Contact Nos. of the Offeror. The 3rd cover duly sealed should be addressed to “The Chief Executive, Bank of India, Kenya Centre, Nairobi. Attention: Mr. Sibasish Tripathy, Chief Manager Operations” and to be delivered at the Office of The Chief Executive, Bank of India Kenya Centre, Kenyatta Avenue, PO Box 30246-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. The sealed offers will be received at above address up to 5.00 pm on 24.03.2016 (last date). -

BANK of INDIA 33X3 (27-8).Indd

P.O. Box 30246 00100 Nairobi Branches in Nairobi * Mombasa * Industrial Area * Westlands * Eldoret Telephone: 2221414-7 Email: [email protected], [email protected] UNAUDITEDUNAUDITEDUNAUDITED FINANCIAL FINANCIAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENTS STATEMENTS AND AND OTHER AND OTHER DISCLOSURESOTHER DISCLOSURES DISCLOSURES FOR THE FORPERIODFOR PERIOD THE ENDED PERIOD ENDED 31ST MARCH 3OENDEDTH JUNE 2019 30 2018TH JUNE 2019 BANK I STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION BANK BANK I. STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION I STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 30th June 2017 31st December 2017 31st March 2018 30th June 2018 Shs.31st ‘000’ March 2018 30th Shs. 31stJune ‘000’ December 31st December 2018Shs. ‘000’ 31st March 31st 2019Shs.March ‘000’ 30th June A ASSETS UnauditedShs. ‘000’ 2018Audited Shs. ‘000’Unaudi2018ted Shs.Unaudi ‘000’2019ted 2019 A ASSETS1 Cash ( both Local & Foreign) 62,964Unaudited 69,114 Audited91,440 Unaudited76,769 1 Cash ( both Local & Foreign) 91,440Shs. ‘000’ 69,666Shs. ‘000’ Shs. 87,228 ‘000’ Shs. ‘000’ A ASSETS2 Balances2 Balances due from due Central from CentralBank of Bank Kenya of Kenya 1,242,0262,228,916Unaudited 2,145,709 2,059,558Audited 2,22 8,916 2,379,869Unaudited 2,956,662 Unaudited 1 Cash3 Kenya ( both3 Government KLocalenya Government& Foreign) and other and securities other securities held for held dealing for dealing purposes purposes 76,769 69,666 87,228 92,665 4 Financial4 Financial Assets at Assets fair value at fair through value through profit profitand loss and loss 2 Balances5 Investment5 dueInvestment from Securities: Central Securities: Bank of Kenya 2,956,662 2,059,558 2,379,869 5,186,527 3 Kenyaa) GovernmentHeld toa) Maturity:Held to and Maturity: other securities held for dealing purposes 27,307,314 -30,079,138 - - - - 4 Financial a. -

I. State Bank of India

COMPANY PROFILE I. STATE BANK OF INDIA OVERVIEW INTERNATIONAL PRESENCE HISTORY ASSOCIATE BANKS BRANCHES State Bank of India (SBI) (BSE: 500112, LSE: SBID) is the largest state- owned banking and financial services company in India, by almost every parameter - revenues, profits, assets, market capitalization, etc. The bank traces its ancestry to British India, through the Imperial Bank of India, to the founding in 1806 of the Bank of Calcutta, making it the oldest commercial bank in the Indian Subcontinent. Bank of Madras merged into the other two presidency banks, Bank of Calcutta and Bank of Bombay to form Imperial Bank of India, which in turn became State Bank of India. The Government of India nationalized the Imperial Bank of India in 1955, with the Reserve Bank of India taking a 60% stake, and renamed it the State Bank of India. In 2008, the Government took over the stake held by the Reserve Bank of India. SBI provides a range of banking products through its vast network of branches in India and overseas, including products aimed at NRIs. The State Bank Group, with over 16,000 branches, has the largest banking branch network in India. With an asset base of $352 billion and $285 billion in deposits, it is a regional banking behemoth. It has a market share among Indian commercial banks of about 20% in deposits and advances, and SBI accounts for almost one- fifth of the nation's loans. SBI has tried to reduce over-staffing by computerizing operations and "golden handshake" schemes that led to a flight of its best and brightest managers.