Working out Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NETC News, Vol. 15, No. 3, Summer 2006

A Quarterly Publication of the New England Theater NETCNews Conference, Inc. volume 15 number 3 summer 2006 The Future is Now! NETC Gassner Competition inside Schwartz and Gleason Among 2006 a Global Event this issue New Haven Convention Highlights April 15th wasn’t just income tax day—it was also the by Tim Fitzgerald, deadline for mailing submissions for NETC’s John 2006 Convention Advisor/ Awards Chairperson Gassner Memorial Playwrighting Award. The award Area News was established in 1967 in memory of John Gassner, page 2 Mark your calendars now for the 2006 New England critic, editor and teacher. More than 300 scripts were Theatre Conference annual convention. The dates are submitted—about a five-fold increase from previous November 16–19, and the place is Omni New Haven years—following an extensive promotional campaign. Opportunities Hotel in the heart of one of the nation’s most exciting page 5 theatre cities—and just an hour from the Big Apple itself! This promises to be a true extravanganza, with We read tragedies, melodramas, verse Ovations workshops and inteviews by some of the leading per- dramas, biographies, farces—everything. sonalities of current American theatre, working today Some have that particular sort of detail that page 6 to create the theatre of tomorrow. The Future is Now! shows that they’re autobiographical, and Upcoming Events Our Major Award recipient this others are utterly fantastic. year will be none other than page 8 the Wicked man himself, Stephen Schwartz. Schwartz is “This year’s submissions really show that the Gassner an award winning composer Award has become one of the major playwrighting and lyricist, known for his work awards,” said the Gassner Committee Chairman, on Broadway in Wicked, Pippin, Steve Capra. -

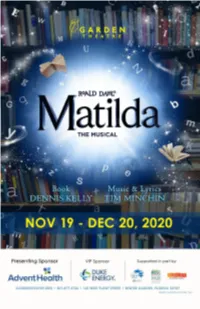

Matilda-Playbill-FINAL.Pdf

We’ve nevER been more ready with child-friendly emergency care you can trust. Now more than ever, we’re taking extra precautions to keep you and your kids safe in our ER. AdventHealth for Children has expert emergency pediatric care with 14 dedicated locations in Central Florida designed with your little one in mind. Feel assured with a child-friendly and scare-free experience available near you at: • AdventHealth Winter Garden 2000 Fowler Grove Blvd | Winter Garden, FL 34787 • AdventHealth Apopka 2100 Ocoee Apopka Road | Apopka, Florida 32703 Emergency experts | Specialized pediatric training | Kid-friendly environments 407-303-KIDS | AdventHealthforChildren.com/ER 20-AHWG-10905 A part of AdventHealth Orlando Joseph C. Walsh, Artistic Director Elisa Spencer-Kaplan, Managing Director Book by Music and Lyrics by Dennis Kelly Tim Minchin Orchestrations and Additional Music Chris Nightingale Presenting Sponsor: ADVENTHEALTH VIP Sponsor: DUKE ENERGY Matilda was first commissioned and produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered at The Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England on 9 November 2010. It transferred to the Cambridge Theatre in the West End of London on 25 October 2011 and received its US premiere at the Shubert Theatre, Broadway, USA on 4 March 2013. ROALD DAHL’S MATILDA THE MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI) All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 423 West 55th Street, New York, NY 10019 Tel: (212)541-4684 Fax: (212)397-4684 www.MTIShows.com SPECIAL THANKS Garden Theatre would like to thank these extraordinary partners, with- out whom this production of Matilda would not be possible: FX Design Group; 1st Choice Door & Millwork; Toole’s Ace Hardware; Signing Shadows; and the City of Winter Garden. -

AS YOU LIKE IT, the First Production of Our 50Th Anniversary Season, and the First Show in Our Shakespearean Act

Welcome It is my pleasure to welcome you to AS YOU LIKE IT, the first production of our 50th anniversary season, and the first show in our Shakespearean act. Shakespeare’s plays have been a cornerstone of our work at CSC, and his writing continues to reflect and refract our triumphs and trials as individuals and collectively as a society. We inevitability turn to Shakespeare to express our despair, bewilderment, and delight. So, what better place to start our anniversary year than with the contemplative search for self and belonging in As You Like It. At the heart of this beautiful play is a speech that so perfectly encapsulates our mortality. All the world’s a stage, and we go through so many changes as we make our exits and our entrances. You will have noticed many changes for CSC. We have a new look, new membership opportunities, and are programming in a new way with more productions and a season that splits into what we have called “acts.” Each act focuses either on a playwright or on an era of work. It seemed appropriate to inaugurate this with a mini-season of Shakespeare, which continues with Fiasco Theater's TWELFTH NIGHT. Then there is Act II: Americans dedicated to work by American playwrights Terrence McNally (FIRE AND AIR) and Tennessee Williams (SUMMER AND SMOKE); very little of our repertoire has focused on classics written by Americans. This act also premieres a new play by Terrence McNally, as I feel that the word classic can also encapsulate the “bigger idea” and need not always be the work of a writer from the past. -

The Full Monty | Facing up to the Challenge of the Coronavirus Labour Market Crisis 2

The Full Monty Facing up to the challenge of the coronavirus labour market crisis Nye Cominetti, Laura Gardiner & Hannah Slaughter June 2020 resolutionfoundation.org @resfoundation The Full Monty | Facing up to the challenge of the coronavirus labour market crisis 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Graeme Cooke for his many useful contributions to this paper. We would also like to thank those who took part in a roundtable to discuss the ideas in this report: Tony Wilson, Kate Bell, Dan Finn, Stephen Evans, Matthew Percival, and Elena Magrini. Of course, all view and any errors remain the authors’ own. This research uses data from an online survey conducted by YouGov and funded by the Health Foundation. The figures presented from the online survey have been analysed independently by the Resolution Foundation. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Health Foundation or YouGov. Download This document is available to download as a free PDF at: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/the-full-monty/ Citation If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is: N Cominetti, L Gardiner & H Slaughter, The Full Monty: Facing up to the challenge of the coronavirus labour market crisis , Resolution Foundation, June 2020 Permission to share This document is published under the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 England and Wales Licence. This allows anyone to download, reuse, reprint, distribute, and/or copy Resolution Foundation publications without written -

The God of Carnage

Presents Yasmina Reza’s The God Of Carnage Opening Night: Feb 15th 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25 February at 7 p.m. 17, 24 February at 4 p.m. at Teater Brunnsgatan 4 THE GOD OF CARNAGE - Following a playground altercation between two 11-year-old boys in an affluent London neighborhood, the parents agree to meet to discuss the situation civilly. However, the facade of polite society soon falls away as the two couples regress to childish accusations, bullying and bickering themselves. Originally written in French and entitled Le Dieu du Carnage, The God of Carnage premiered in 2006 at the Schauspielhaus in Zurich directed by Jürgen Gosch and it made its French-language debut at the Théâtre Antoine in Paris in January 2008 directed by the author. Reza’s long-time collaborator Christopher Hampton translated and adapted an English-language version that premiered at the Gielgud Theatre in London’s West End in March 2008 and the production won the 2009 Olivier Award for Best New Comedy. Hampton further adapted the script for an Americanized edition, which premiered on Broadway at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in February 2009 and the production won Best Play (Reza’s second win). The international popularity of the play led to a film adaptation called Carnage, which premiered in Italy at the Venice Film Festival before being released in the United Stated in September 2011. Written by Reza with director Roman Polanski, the film starred Jodie Foster, Kate Winslet, John C. Reilly and Christoph Waltz. ABOUT SEST SEST – The Stockholm English Speaking Theatre, now in its third year, presents Yasmina Reza’s The God of Carnage, translated by Christopher Hampton, from Feb 15 to Feb 25 at Teater Brunnsgatan 4. -

The Full Monty

Warren Gerds/Critic at Large: Review: Published 07/28 2016 08:47AM Updated 07/28 2016 12:58PM By Warren Gerds | [email protected] Creative: Based on the 1997 film with screen- play by Simon Beaufoy: music and lyrics – David Yazbeck; book – Terrence McNally; director – Greg Vinkler; music director – Valerie Maze; choreography – William Carlos Angulo; orchestrations – Harold Wheeler; scenic designer – Jack Magaw; lighting designer – Jason Fassl; costume designer – Nan Zabriskie; sound designer – Megan B. Henninger; properties designer – Sarah E. Ross; wig master – Kyle Pingel; scenic artist – Christine Bolles; dance music arrangements – Zan Mark; vocal and incidental music arrangements – Ted Sperling; stage manager – William Collins; assistant stage manager – Heather Bannon; production manager – Laura Eilers Cast (in order of appearance): Georgie Bukatinsky– Brianna Borger; Buddy (Keno) Walsh – Samuel Owen Gardner; Reg Willoughby/Dance Instructor/Minister – James Leaming; Gary Bonasorte/Teddy Slaughter – Matt Holzfeind; Marty/Tony Characters of the fictional dance group Hot Metal perform a scene in the Peninsula Players Giordano – Mark Moede; Jerry Lukowski – Theatre production of /Len Villano/Peninsula Players Theatre . From left actors Steve Adrian Aguilar; Dave Bukatinsky – Matthew Scott Campbell; Malcolm MacGregor– Koehler, Harter Clingman, Matthew Scott Campbell, Adrian Aguliar, Jackson Evans and Harter Clingman; Ethan Girard – Jackson Byron Glenn Willis. On stage through August 14, 2016. Evans; Nathan Lukowski – Hayden Hoffman; Susan Hershey/Young Woman – Katherine Duffy; Joanie Lish/Molly MacGregor– Erica Elam; Estelle Genovese – Ashley Lanyon; Pam Lukowski – Katherine Keberlein; Second ‘The Full Monty' electrifies in Stripper/Dancer – Peter Brian Kelly; Vicki Nichols – Maggie Carney; Harold Nichols – Steve Koehler; Jeanette Burmeister– Peggy Door County Roeder; Noah (Horse) T. -

“The Full Monty”, the 1997 British Comedy Film Directed by Peter Cattaneo, Tells a Complex Economic Story for the Viewer with a Critical Eye

“The Full Monty”, the 1997 British comedy film directed by Peter Cattaneo, tells a complex economic story for the viewer with a critical eye. The end of the story, insofar as we can see from the movie, may appear utterly ridiculous at first glance. A group of regular guys stripping naked and dancing seductively in front of their wives and fellow townspeople is shocking. But these guys reached this point as a result of a variety of circumstances that deserve some examination. In this paper, I will consider four distinct economic phases which I believe are relevant to the characters’ lives. No particular economic theory is sufficient to explain what happened in Sheffield, England in reality or within the film. I will utilize various economic concepts and draw from renowned economic thinkers to present “The Full Monty”’s economic story. First, however, it is necessary to give a little background regarding the steel industry in northern England and the changes that occurred there by the time of the film. The city of Sheffield is located in South Yorkshire, England where the effects of the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century were extremely significant. In 1856, Henry Bessemer developed a technique in Sheffield which allowed for the mass production of steel (Investinsheffield). This development essentially made Sheffield king of the steel world. Its products, which included stainless steel cutlery and railroad tracks, were shipped around Europe and across the Atlantic to America. Though both the United States and Germany had overtaken Britain in terms of steel output by 1890, Sheffield’s dominance in the industry continued through the middle of the twentieth century. -

City Center Announces Casting for 1776

Contact: Joe Guttridge, Director, Communications [email protected] 212.763.1279 John Behlmann, Nikki Renée Daniels, André De Shields, Santino Fontana, Alexander Gemignani, John Larroquette, Christiane Noll, Bryce Pinkham, Jubilant Sykes, and more will star in the Encores! production of 1776, directed by Garry Hynes, Mar 30—Apr 3 February 29, 2016/New York, NY—Encores! Artistic Director Jack Viertel today announced casting for the Encores! production of 1776, the classic Tony Award-winning musical about how the founding fathers drafted the Declaration of Independence and gave birth to a new nation. 1776 will star Terence Archie, John Behlmann, Larry Bull, Nikki Renée Daniels, André De Shields, Macintyre Dixon, Santino Fontana, Alexander Gemignani, John Hickok, John Hillner, John Larroquette, Kevin Ligon, John-Michael Lyles, Laird Mackintosh, Michael McCormick, Michael Medeiros, Christiane Noll, Bryce Pinkham, Wayne Pretlow, Tom Alan Robbins, Robert Sella, Ric Stoneback, Jubilant Sykes, Vishal Vaidya, Nicholas Ward, and Jacob Keith Watson. A unique show that presents John Adams (Santino Fontana), Thomas Jefferson (John Behlmann), and Benjamin Franklin (John Larroquette) in all their fractious, fascinating complexity, 1776 features such beloved songs as “Sit Down, John,” “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men,” and “He Plays the Violin.” Written by Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone, 1776 opened on Broadway on March 16, 1969, and ran for 1217 performances. The Encores! production will be directed by Garry Hynes, and choreography by Chris Bailey -

André De Shields: Old Dawg; New Tricks

Wednesday, January 29, 2020 at 8:30 pm André De Shields: Old Dawg; New Tricks Liam Robinson, Piano, Conductor, Vocal Arrangements Michael Chorney, Guitar Cody Owen Stine, Keyboard and Guitar Dan Rieser, Drums The Program Brad Christopher Jones, Bass Patience Higgins, Reeds Curtis Fowlkes, Trombone TheRhinestoneRockStarBoogieWoogieDollBabies Freida Williams, Vocals Marléne Danielle, Vocals Larry Spivack, Orchestrator Todd Sickafoose, Orchestrator This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. This performance is being livestreamed; cameras will be present. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Endowment support provided by Bank of America Corporate support provided by Morgan Stanley This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano The Appel Room Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall American Songbook Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Christina and Robert Baker, EY, Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Patrons and Lincoln Center Members Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Artist catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING AMERICAN SONGBOOK EVENTS -

PRT 2021 Season Program

PRT IS BACK FOR A 50th YEAR! PRAIRIE REPERTORY THEATRETHEATRE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY The Compl.ete Works of ´ | ™ | ® | © WILLIAM THE GIN SHAKESPEARE By Adam Long, [abridged] Daniel Singer and Jess Winfield GABy D.L.CMoburn E Book and Lyrics by Howard Ashman, Music by Alan Menken LITTLE O I SHOP F I QUILTERS HORRORS By Molly Newman and Barbara Damashek Welcome! Table of Contents Dear Friends of Prairie Repertory Theatre- 1. Greetings from Managing/Artistic Director Thank you so much for joining us for this production. We are de- J.D. Ackman lighted you have chosen to make our 50th season part of your sum- mer. Having canceled our 2020 season, we are especially delighted to be back for 2021. The effects of the pandemic have been felt in so 2. The 2021 PRT Company many different ways, and particularly in the performing arts. We are truly fortunate to enjoy the support of South Dakota State Univer- 3. PRT Board of Directors sity in planning, creating, and presenting our summer season in the safest possible way. 4. Greetings from President Barry Dunn PRT’s mission is: 1) to provide intensive training for students in the company, and 2) to provide you with the best possible entertain- 5. The Complete Works of ment. We are proud of our continuing efforts to fulfill our mission. William Shakespeare (abridged) It is truly a joy to work with these young theatre artists as they learn and grow through the process of rehearsing and mounting our 6. Meet the 2019 Company! shows. This group will have worked more than 300 hours by the time Little Shop of Horrors opens. -

Virtual Live Auction 5 Pm on Sunday, September 20

Virtual Live Auction 5 pm on Sunday, September 20 Auctioneer: Nick Nicholson Host: Bryan Batt 1. Join Seth Rudetsky and James Wesley as a Special Guest on Stars in the House Your name will be added to the roster of entertainment luminaries when you join Seth Rudetsky and James Wesley as a special guest on an episode of Stars in the House. Created in response to the coronavirus pandemic, Stars in the House brings together music, community and education. Benefiting The Actors Fund, the daily livestream features remote performances from stars in their homes, conversing with Rudetsky and Wesley in between songs. The incredible 800 guests so far have included everyone from Annette Benning to Jon Hamm to Phillipa Soo. Don’t miss the opportunity to join for an episode and make your smashing debut as a special guest on Stars in the House. Opening bid: $500 2. Virtual Meeting with the Legendary Bernadette Peters There are few leading ladies as notably creative and compassionate as Bernadette Peters. The two-time Tony Award winner made her Broadway debut in 1967’s The Girl in the Freudian Slip. In the decades since, she’s created some of musical theater’s most memorable roles including Dot in Sunday in the Park with George and The Witch in Into the Woods. She’s a member of the Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS Board of Trustees who has created memorable performances in stunning Broadway revivals, notably Annie Get Your Gun, Gypsy, Follies and, most recently, Hello Dolly!. Today, you can win a virtual meet-and-greet with this legend. -

The Fortress of Solitude

Contact: Kelsey Guy, Director of Public Relations (214) 252-3923 ❘ [email protected] Dallas Theater Center Presents the World Premiere Musical The Fortress of Solitude A Co-Production with The Public Theater Based on the Novel by Jonathan Lethem Book by Itamar Moses • Music and Lyrics by Michael Friedman Conceived and Directed by Daniel Aukin Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre at the AT&T Performing Arts Center • 2400 Flora Street Previews: March 7 - 13, 2014 • Full Run: March 7 – April 6, 2014 • Press Opening: Fri., March 14 at 8:00 p.m. Tickets: 214-880-0202 or www.DallasTheaterCenter.org DALLAS (February 6, 2014) – Dallas Theater Center announced today the award-winning cast and creative team for the world premiere new musical The Fortress of Solitude, a co-production with The Public Theater in New York City. The Fortress of Solitude is based on the nationally best-selling novel of the same name by 2005 MacArthur Fellow Jonathan Lethem. The musical is conceived and directed by Daniel Aukin, with a book by Itamar Moses, and music and lyrics by Michael Friedman. The Fortress of Solitude opens with previews on March 7 and runs through April 6. Tickets to this stunning new musical, The Fortress of Solitude, are on sale now at www.DallasTheaterCenter.org and by phone at (214) 880-0202. Aukin has previously directed critically acclaimed productions at New York’s Roundabout Theatre Company, Lincoln Center and Manhattan Theatre Club. “The notion of adapting this gorgeous novel into a musical was terrifying and thrilling and, finally, inescapable,” says Aukin.