The French Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mali: a Neo-Colonial Operation Disguised As an Anti-Terrorist Intervention*

Mali: A Neo-Colonial Operation Disguised as an Anti-Terrorist Intervention* Translated by Dan La Botz In mid-January of this year France invaded Mali, a former French colony that sits in the middle of what was once the enormous French empire in Africa that stretched from Algeria to the Congo and from the Ivory Coast to the Sudan. The French government argued that its invasion of its former colony was an anti-terrorist and humanitarian intervention to prevent radical Salafist Muslims from taking the capital of Bamako and succeeding in taking control of the country. Critics have suggested that France had other motivations, above all maintaining its powerful influence in the region in order to prevent European competitors, the United States, or the Chinese from muscling in, but also because of its specific interests in resources such as uranium. The situation is very complex, in part because of a historic division and even antagonism between the Tuaregs, a Berber people in the North of Mali, and the black African population in the South, but also because, in addition to the various Islamist groups, there are also numerous organizations of traffickers in drugs and other contraband. In this article, Jean Batou unravels the complexity of the situation to lay bare the central social struggles taking place. – Editors Looking back on events, it’s important to point out the real ins-and-outs of the French military intervention in Mali, launched officially on January 11 on the pretext of preventing a column of Salafist pick-up trucks from swooping down on the city of Mopti and the nearby Sévaré airport (640 km north of Bamako), and thus supposedly opening the way to Bamako, the capital and the country’s largest city. -

Paul Touvier and the Crime Against Humanity'

Paul Touvier and the Crime Against Humanity' MICHAEL E. TIGARt SUSAN C. CASEYtt ISABELLE GIORDANItM SIVAKUMAREN MARDEMOOTOOt Hi SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION ............................................... 286 II. VICHY FRANCE: THE BACKGROUND ................................ 286 III. TOUVIER'S ROLE IN VICHY FRANCE ................................ 288 IV. THE CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY ................................. 291 A The August 1945 Charter ................................... 291 B. The French Penal Code .................................... 293 C. The Barbie Case: Too Clever by Half ........................... 294 V. THE TouviER LITIGATION ....................................... 296 A The Events SurroundingTouvier's Captureand the PretrialLegal Battle ... 296 B. Touvier's Day in Court ..................................... 299 VI. LEGAL ANALYSIS: THE STATE AGENCY DILEMMA.. ...................... 304 VII. CONCLUSION ............................................... 309 " The idea for this essay began at a discussion of the Touvier trial with Professor Tigar's students at the Facut de Droit at Aix-en-Provence, with the assistance of Professor Andr6 Baldous. Ms. Casey provided further impetus for it by her research assistance on international human rights issues, and continued with research and editorial work as the essay developed. Ms. Giordani researched French law and procedure and obtained original sources. Mr. Mardemootoo worked on further research and assisted in formulating the issues. The translations of most French materials were initially done by Professor Tigar and reviewed by Ms. Giordani and Mr. Mardemootoo. As we were working on the project, the Texas InternationalLaw Journaleditors told us of Ms. Finkelstein's article, and we decided to turn our effort into a complementary piece that drew some slightly different conclusions. if Professor of Law and holder of the Joseph D. Jamail Centennial Chair in Law, The University of Texas School of Law. J# J.D. -

Politicizing the Crime Against Humanity: the French Example

University of Pittsburgh School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications 2003 Politicizing the Crime Against Humanity: The French Example Vivian Grosswald Curran University of Pittsburgh School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, European Law Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Commons, Legal History Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Vivian G. Curran, Politicizing the Crime Against Humanity: The French Example, 78 Notre Dame Law Review 677 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/424 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PROPTER HONORIS RESPECTUM POLITICIZING THE CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY: THE FRENCH EXAMPLE Vivian Grosswald Curran* C'est une lourde tdche, pour le philosophe, d'arracherles noms a ce qui en prostitue l'usage. Dojd Platon avait toutes les peines du monde d tenirferme sur le mot justice contre l'usage chicanier et versatile qu'en faisaient les sophistes. 1 INTRODUCTION The advantages of world adherence to universally acceptable standards of law and fundamental rights seemed apparent after the Second World War, as they had after the First.2 Their appeal seems ever greater and their advocates ever more persuasive today. -

The Trial of Paul Touvier

A CENTURY OF GENOCIDES AND JUSTICE: THE TRIAL OF PAUL TOUVIER An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by RACHEL HAGE Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. Richard Golsan May 2020 Major: International Studies, International Politics and Diplomacy Track TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................1 Literature Review.....................................................................................................1 Thesis Statement ......................................................................................................1 Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................2 Project Description...................................................................................................2 KEY WORDS ..................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................5 United Nations Rome Statute ..................................................................................5 20th Century Genocide .............................................................................................6 -

Süveyş Krizi'ne Giden Yolda Fransa'nın Israil Politikası

Ankara Avrupa Çalışmaları Dergisi Cilt:17, No:1 (Yıl: 2018), s. 99-126 FRANSIZ DÖRDÜNCÜ CUMHURİYETİ’NDE SİYASAL YAPI VE DIŞ POLİTİKA: SÜVEYŞ KRİZİ’NE GİDEN YOLDA FRANSA’NIN İSRAİL POLİTİKASI Çınar ÖZEN Nuri YEŞİLYURT** Özet Bu makale, Fransız Dördüncü Cumhuriyeti’nin siyasal yapısının dış politika üzerindeki etkisini analiz etmeyi amaçlamaktadır. Bu analizi, Süveyş Krizi’ne giden yolda Fransa’nın İsrail’e karşı izlediği politika üzerinden yapmaktadır. Fransa’nın bu krizde kritik bir rol oynadığını savlayan makale, Paris’in bu politikasını açıklayabilmek için Dördüncü Cumhuriyetin zayıf ve istikrarsız siyasal yapısı içerisinde öne çıkan savunma ve dışişleri bürokrasileri arasında bürokratik siyaset modeli çerçevesinde cereyan eden iç mücadeleye odaklanmaktadır. Bu mücadelede Savunma Bakanlığı bürokrasisinin galip gelmesinde bir dizi bölgesel gelişme etkili olmuş ve sonuçta Fransa, Mısır’a yönelik ortak askerî müdahalenin planlanmasında öncü bir rol oynamıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Fransa, İsrail, Dördüncü Cumhuriyet, Süveyş Krizi, bürokratik siyaset Political Structure and Foreıgn Policy of the French Fourth Republic: French Policy Towards Israel on the Road to Suez Crisis Abstract This article aims to analyse the effect of the political structure of the French Fourth Republic on foreign policy. It makes this analysis over the case of French foreign policy towards Israel on the road to Suez Crisis. The article argues that France played a critical role in this crisis, and in order to explain the policy of Paris, it focuses on the internal struggle that took place between the foreign and defence bureaucracies, which came to the fore thanks to the weak and unstable political structure of the Fourth Republic, under the framework of bureaucratic Prof. -

1961-1962, L'oas De Métropole

1961-1962, l’O.A.S. de Métropole : étude des membres d’une organisation terroriste Sylvain Gricourt To cite this version: Sylvain Gricourt. 1961-1962, l’O.A.S. de Métropole : étude des membres d’une organisation terroriste. Histoire. 2015. dumas-01244341 HAL Id: dumas-01244341 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01244341 Submitted on 15 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1 - Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR 09 Master Histoire des Sociétés occidentales contemporaines Centre d’histoire sociale du XXe siècle 1961-1962, l’O.A.S. de Métropole : Étude des membres d’une organisation terroriste Mémoire de Master 2 recherche Présenté par M. Sylvain Gricourt Sous la direction de Mme Raphaëlle Branche 2015 2 1961-1962, l’O.A.S. de Métropole : Étude des membres d’une organisation terroriste 3 Remerciements Ma gratitude va tout d’abord à madame Raphaëlle Branche, ma directrice de mémoire, qui m’a orienté vers l’étude de cette Organisation armée secrète dont les quelques mois d’activité se sont révélés être aussi agités que captivants. Son aide et ses conseils tout au long de ce travail auront été précieux. -

Camille Robcis the Biopolitics of Dignity

South Atlantic Quarterly Camille Robcis The Biopolitics of Dignity “Let us not allow, within a free nation, monuments of slavery, even voluntary.” —Pierre Anastase Torné, French deputy, April 6, 1792 A few days after the shocking attacks on the ofces of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, several French political leaders called for the revival of the “crime of national indignity” as a possible sanction against terrorists of French citizenship. As the prime minister Manuel Valls put it, such a measure—backed up, according to surveys, by 76 percent of the French population—would “mark with symbolic force the consequences of the absolute transgression that a terrorist act con- stitutes” (Clavel 2015). Under French law, national indignity did indeed have a particular history and signifcation, one that was not simply “symbolic” but in fact quite concrete. As the historian Anne Simonin (2008) shows, “national indignity” was invented in 1944 by the legal experts of the Resis- tance as an exceptional measure to punish, retro- actively, the supporters of the Vichy regime who had collaborated with the Nazi occupiers and pro- moted anti-Semitic legislation. Between 1945 and 1951, around one hundred thousand citizens were The South Atlantic Quarterly 115:2, April 2016 doi 10.1215/00382876-3488431 © 2016 Duke University Press Published by Duke University Press South Atlantic Quarterly 314 The South Atlantic Quarterly • April 2016 accused of indignity and punished by “national degradation.” In practical terms, this meant that they were stripped of their civic rights and their pos- sessions, banned from exercising certain public positions and professions (lawyers, bankers, teachers), and forbidden to live in particular regions of France. -

Serge Klarsfeld

Grand Oral Serge 1984 - 2014 1984 KLARSFELD • Écrivain, historien et avocat, président de l’Association des Fils et Filles des Déportés Juifs de France, vice- président de la Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah 30 ANS DE RENCONTRES 30 DE RENCONTRES ANS en partenariat avec le Mémorial de la Shoah et la librairie Mollat « Jury » présidé par Bernadette DUBOURG, Journaliste à Sud Ouest Jeudi 4 décembre 2014 1984 - 2014 17h00 – 19h00 • Amphi Montesquieu • Sciences Po Bordeaux 330 ANS0 INTRODUCTION Les Rencontres Sciences Po/Sud Ouest ont pour vocation de faire découvrir, à l’occasion de leurs Grands Oraux, des personnalités dont le parcours et l’œuvre sont dignes d’intérêt et parfois même tout à fait exceptionnels. Avec Serge Klarsfeld nous sommes face à un engagement exceptionnel qui constitue l’œuvre d’une vie : la poursuite des criminels nazis et de leurs complices et un travail patient, fastidieux de mémoire pour reconstituer l’identité et l’itinéraire des 76 000 déportés Juifs de France. Telle est l’œuvre de cet avocat, historien qui préside l’association des Fils et Filles des Déportés Juifs de France. Cette quête de vérité l’a poussé avec sa femme, Beate, à traquer par tous les moyens d’anciens nazis comme Klaus Barbie et à dépouiller inlassablement les archives. Une vie de combat obstiné pour que soient jugés à Cologne en 1979, Kurt Lischka, Herbert Hagen , Ernst Heinrichsohn, trois des principaux responsables de la Solution finale en France, que soient inculpés les Français René Bousquet ou Jean Leguay et jugé et condamné Maurice Papon en avril 1998 pour complicité de crime contre l’humanité. -

Alya Aglan La France À L’Envers La Guerre De Vichy (1940-1945) INÉDIT Histoire

Alya Aglan La France à l’envers La guerre de Vichy (1940-1945) INÉDIT histoire COLLECTION FOLIO HISTOIRE Alya Aglan La France à l’envers La guerre de Vichy 1940‑1945 Gallimard Cet ouvrage inédit est publié sous la direction de Martine Allaire Éditions Gallimard, 2020. Les bobards… sortent toujours du même nid. Affiche de propagande vichyste, 1941, par André Deran. Collection particulière. Photo © Bridgeman Images. Alya Aglan, née en 1963 au Caire, est professeur d’histoire contemporaine à l’université Paris 1 Panthéon‑Sorbonne, titu‑ laire de la chaire « Guerre, Politique, Société, XIXe‑XXe siècle ». Spécialiste de l’histoire de la Résistance, abordée sous l’angle de la perception du temps aussi bien par les orga‑ nisations que par les acteurs individuels, elle a été chargée par la Caisse des dépôts et consignations, dans le contexte de la Mission Matteoli, d’étudier le mécanisme administra‑ tif des spoliations antisémites sous Vichy. Introduction Parenthèse politique, « quatre années à rayer de notre histoire1 », selon le procureur général Mornet, où seule « une poignée de misérables et d’indignes2 » se seraient rendus coupables d’« intelligence avec l’ennemi », l’Occupation et le régime de Vichy n’ont pas réussi à entamer l’identification de la nation française à son glorieux passé national et impérial en dépit de fractures profondément rouvertes en 1940. Pourtant la continuité inentamée du déroulé his‑ torique, qui s’incarne de manière inattendue dans la France libre, rebelle ou « dissidente », aurait sim‑ plement migré, provisoirement, de Paris à Londres en 1940, puis à Alger fin 1942, avant de revenir dans la capitale des Français. -

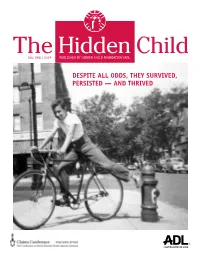

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

Programme 4Th World Forum on Human Rights

FORUM_2010_PRG_GB_COUV1_EXE:Mise en page 1 09/06/10 19:18 Page1 4TH WORLD FORUM ON HUMAN RIGHTS In a world in crisis, what about Human Rights? PROGRAMME JUNE 28 TO JULY 1, 2010 NANTES - FRANCELA CITÉ - NANTES EVENTS CENTER From universal principles to local action Monday 28th June Lascaux Meetings From land to food, from values to rules – Official opening ceremony Room 450 Room 300 Rooms 200, 150-A, 150-B and Balcony Room 120 Room J Auditorium 2000 9:30 am Lascaux Meetings From the land to food: review of Children's Rights Day the key questions, problems and Shackles 12 noon expectations. of Memory 2:00 pm Young people From the land to International Meeting on the Children's Rights at the centre food: what is the Alliance central themes of Day: performance of the World Forum situation with the World Alliance by Compagnie Ô on Human Rights regard to rights of Cities Against to land and food? Poverty 6:30 pm Auditorium 2000: Official opening ceremony Tuesday 29th June Identities and minorities: living and acting together in diversity Room 450 Room 300 Room 200 Room 150-A Room 150-B Room 120 Room GH Room BC 9:30 am Cities and the Lascaux Meetings People, citizenship, Indigenous Access to citizenship Poor children Reflecting upon Global Crisis: how Agricultural equality, identity: peoples’ right and strengthening and single parent and building can human rights development can difference of access borders in Europe: families: when the citizenship in be protected? and the reduction and diversity to land towards better inte- exercise of family countries with of poverty. -

Klaus Barbie Pre-Trial Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt509nf111 No online items Inventory of the Klaus Barbie pre-trial records Finding aid prepared by Josh Giglio. Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2008, 2014 Inventory of the Klaus Barbie 95008 1 pre-trial records Title: Klaus Barbie pre-trial records Date (inclusive): 1943-1985 Collection Number: 95008 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of the Materials : In French and German. Physical Description: 8 manuscript boxes(3.2 linear feet) Abstract: Trial instruction, including depositions and exhibits, in the case of Klaus Barbie before the Tribunal de grande instance de Lyon, relating to German war crimes in France during World War II. Photocopy. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Barbie, Klaus, 1913- , defendant. Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1995. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu/ .