American Cultural Icons Defining the Cold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020 C O N T E N T S

The CRIMSON HISTORICAL REVIEW An Undergraduate Journal of History at the University of Alabama Volume II, No. II Spring 2020 C O N T E N T S Staff Information ii Contributors Page iii Letter from the Chief Editor Jodi Vadinsky iv A R T I C L E S Demystifying Feminine Ireland During Cecilia Barnard 01 the Rebellion of 1798 Borders and Bodies: The El Paso Eve Galanis 13 Quarantine and Mexican Women’s Resistance Chile: Democracy to Destabilization to Ethan Legrand 29 Dictatorship Turning Point of Cold War Diplomacy: Reuben Francis 41 The Impact of the South Asian Crisis of 1971 on US-Chinese Rapprochement Of Course Someone You Know Is Gay: Victoria Carl 60 Alabama’s Gay Student Union, 1983- 1984 i S T A F F Executive Board Review Board Associates Faculty Editor Cecilia Barnard Nikolas Clark Dr. Margaret Peacock Mariella Giordano Lindsey Glick Troy Watley Declan Smith Chief Editor Katie Kroft Philip Marini Jodi Vadinsky Griffin Specker Jacob Wolfe Production Editor Ashley Terry Caroline Lawrence Lily Mears Jasmine James Jackson C. Foster Logan Goulart Noah Dasinger Production Editor Elect Riley LoCurto James Gibbs John Pace Courtney Lowery Design Editor Copy Editors Charlie Wright Kenzie Wilbourne Ashley Terry Review Board Executive Corinne Baroni Lily Mears Claire Sullivan Aaron Eitson The Crimson Historical Review is composed of undergraduate students at the University of Alabama who are passionate about history, academic writing, and publishing. Interested in becoming a staff member? Undergraduate students at the University of Alabama are invited to contact [email protected]. The CHR is not operated by the University of Alabama. -

The Us Constitution As Icon

EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM THE U.S. CONSTITUTION AS ICON: RE-IMAGINING THE SACRED SECULAR IN THE AGE OF USER-CONTROLLED MEDIA Michael M. Epstein* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 II. CULTURAL ICONS AND THE SACRED SECULAR…………………..... 3 III. THE CAREFULLY ENHANCED CONSTITUTION ON BROADCAST TELEVISION………………………………………………………… 7 IV. THE ICON ON THE INTERNET: UNFILTERED AND RE-IMAGINED….. 14 V. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………….... 25 I. INTRODUCTION Bugs Bunny pretends to be a professor in a vaudeville routine that sings the praises of the United States Constitution.1 Star Trek’s Captain Kirk recites the American Constitution’s Preamble to an assembly of primitive “Yankees” on a far-away planet.2 A groovy Schoolhouse Rock song joyfully tells a story about how the Constitution helped a “brand-new” nation.3 In the * Professor of Law, Southwestern Law School. J.D. Columbia; Ph.D. Michigan (American Culture). Supervising Editor, Journal of International Media and Entertainment Law, and Director, Amicus Project at Southwestern Law School. My thanks to my colleague Michael Frost for reviewing some of this material in progress; and to my past and current student researchers, Melissa Swayze, Nazgole Hashemi, and Melissa Agnetti. 1. Looney Tunes: The U.S. Constitution P.S.A. (Warner Bros. Inc. 1986), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5zumFJx950. 2. Star Trek: The Omega Glory (NBC television broadcast Mar. 1, 1968), http://bewiseandknow.com/star-trek-the-omega-glory. 3. Schoolhouse Rock!: The Preamble (ABC television broadcast Nov. 1, 1975), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHp7sMqPL0g. 1 EPSTEIN FINAL2.3.2016 (DO NOT DELETE) 2/3/2016 12:04 PM 2 SOUTHWESTERN LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

Re-Imagining Indians: the Counter-Hegemonic Represenations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre

Re-Imagining Indians: The Counter-Hegemonic Represenations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cassadore, Edison Duane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 09:39:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195409 RE-IMAGINING INDIANS: THE COUNTER-HEGEMONIC REPRESENTATIONS OF VICTOR MASAYESVA AND CHRIS EYRE by Edison Duane Cassadore _______________________ Copyright © Edison Duane Cassadore 2007 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 7 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Edison Cassadore entitled Re-Imagining Indians: The Counter-Hegemonic Representations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: September 23, 2005 Barbara Babcock _______________________________________________________________________ -

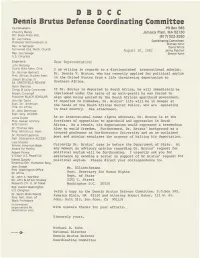

Dear Representative: John Bellamy Coord

• I Co-Convenors: PO Box 585 Chauncy Bailey Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 Dir. Black Press Inst. (617) 522-3260 Dr. Jan Carew Coordinating Committee: Professor Northwestern U. Michael Kohn Rev. AI Sampson David White Fernwood Utd. Meth. Church August 10, 1982 Jenny Patchen Rep. Gus Savage Steven Kahn U.S. Congress Endorsers: Dear Representative: John Bellamy Coord. Biko Mem. Ctte. I am writing in regards to a distinguished international scholar, Dr. Norman Bennett Dr. Dennis V. Brutus, who has recently applied for political asylum Pres. African Studies Assn. in the United States from a life threatening deportation to Joseph Bruchac III Ed. GREEN~ELD REVIEW Southern Africa. Norm Watkins Clergy & Laity Concerned If Dr. Brutus is deported to South Africa, he will immediately be Robert Chrisman imprisoned under the terms of an exit-permit he was forced to Publisher BLACK SCHOLAR sign upon being exiled by the South African apartheid government. Jennifer Davis If deported to Zimbabwe, Dr. Brutus' life will ?e in danger at Exec. Dir. American the hands of the South African Secret Police, who are operating Ctte. On Africa in that country. See attachment. Dr. John Domnisse Exec. Secy. ACCESS Lorna Evans As an international human rights advocate, Dr. Brutus is in the Pres. Hawaii Literary forefront of opposition to apartheid and oppression in South Arts Council Africa. As a result, his deportation would represent a tremendous Dr. Thomas Hale blow to world freedom. Furthermore, Dr~ Brutus' background as a Pres. African Lit. Assn. tenured professor at Northwestern UnIversity and as an acclaimed Dr. Richard Lapchick poet and scholar escalates the urgency of halting his deportation. -

Bibliography of Recent Books in Communications Law

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RECENT BOOKS IN COMMUNICATIONS LAW Patrick J. Petit* The following is a selective bibliography of re- the United States, Germany, and the European cent books in communications law and related Convention on Human Rights. Chapter 1 dis- fields, published in late 1996 or 1997. Each work cusses the philosophical underpinnings of the is accompanied by an annotation describing con- right of privacy; Chapter 2 explores the history of tent and focus. Bibliographies and other useful the development of the right in each of the three information in appendices are also noted. systems. Subsequent chapters examine the struc- ture, coverage, protected scope, content, and who are the subjects of the right to secrecy in telecom- FREEDOM OF PRESS AND SPEECH munications. An extensive bibliography and table of cases is provided. KAHN, BRIAN AND CHARLES NEESONS, EDI- TORS. Borders in Cyberspace: Information Policy and the Global Information Infrastructure. Cambridge, . SAJo, ANDRAS AND MONROE E. PRICE, EDI- Mass.: MIT Press, 1997. 374 p. TORS. Rights of Access to the Media. Boston, Mass.: Borders in Cyberspace is a collection of essays pro- Kluwer Law International, 1996. 303 p. duced by the Center for Law and Information Technology at Harvard Law School. The first part Rights of Access to the Media is a collection of es- of the collection consists of six essays which ad- says which examine the theoretical and practical dress the "where" of cyberspace and the legal is- aspects of media access in the United States and Europe. Part I contains essays by Monroe Price sues which arise because of its lack of borders: ju- risdiction, conflict of laws, cultural sovereignty, and Jean Cohen which address the dominant models of access theory. -

Edward R. Murrow

Edward R. Murrow Edward Roscoe Murrow (April 25, 1908 – April 27, 1965), born Egbert Roscoe Murrow,[1] was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained Edward R. Murrow prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broadcasts from Europe for the news division of CBS. During the war he recruited and worked closely with a team of war correspondents who came to be known as the Murrow Boys. A pioneer of radio and television news broadcasting, Murrow produced a series of reports on his television program See It Now which helped lead to the censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Fellow journalists Eric Sevareid, Ed Bliss, Bill Downs, Dan Rather, and Alexander Kendrick consider Murrow one of journalism's greatest figures, noting his honesty and integrity in delivering the news. Contents Early life Career at CBS Radio Murrow in 1961 World War II Born Egbert Postwar broadcasting career Radio Roscoe Television and films Murrow Criticism of McCarthyism April 25, Later television career Fall from favor 1908 Summary of television work Guilford United States Information Agency (USIA) Director County, North Death Carolina, Honors U.S. Legacy Works Died April 27, Filmography 1965 Books (aged 57) References Pawling, New External links and references Biographies and articles York, U.S. Programs Resting Glen Arden place Farm Early life 41°34′15.7″N 73°36′33.6″W Murrow was born Egbert Roscoe Murrow at Polecat Creek, near Greensboro,[2] in Guilford County, North Carolina, the son of Roscoe Conklin Murrow and Ethel F. (née Lamb) Alma mater Washington [3] Murrow. -

Czechoslovak-Polish Relations 1918-1968: the Prospects for Mutual Support in the Case of Revolt

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt Stephen Edward Medvec The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Medvec, Stephen Edward, "Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5197. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CZECHOSLOVAK-POLISH RELATIONS, 191(3-1968: THE PROSPECTS FOR MUTUAL SUPPORT IN THE CASE OF REVOLT By Stephen E. Medvec B. A. , University of Montana,. 1972. Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: ^ .'■\4 i Chairman, Board of Examiners raduat'e School Date UMI Number: EP40661 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Eddie Awards Issue

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE EDDIE AWARDS ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Golden Eddie Honoree GUILLERMO DEL TORO Career Achievement Honorees JERROLD L. LUDWIG, ACE and CRAIG MCKAY, ACE PLUS ALL THE WINNERS... FEATURING DUMBO HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 1 / 2019 / VOL 69 Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Captive Nations Week, 1999

Proclamations Proc. 7209 Proclamation 7209 of July 16, 1999 Captive Nations Week, 1999 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation This month Americans mark 223 years of freedom from tyranny. We cele- brate the vision of our founders who, in signing the Declaration of Inde- pendence, proclaimed the importance of liberty, the value of human dig- nity, and the need for a new form of government dedicated to the will of the people. As heirs to that legacy and the fortunate citizens of a demo- cratic Nation, we continue to cherish the values of freedom and equality. Many people across the globe, however, are still denied the rights we exer- cise daily and too often take for granted. During Captive Nations Week, we reaffirm our solidarity with those around the world who suffer under the shadow of dictators and tyrants. Americans have expressed their devotion to freedom and human rights through actions as well as words, having fought and died for these ideals time and again. In World War II, we battled the brutality of fascism. In Korea, Vietnam, and throughout the Cold War, we stood up to the des- potism of communism. In the Persian Gulf, and in partnership with our NATO allies in the skies over Serbia and Kosovo, we have fought brutal and oppressive regimes. Thanks to our strength and resolve and the courage of countless men and women in countries around the world, we can be proud that the list of cap- tive nations has grown smaller. The fall of the Berlin Wall a decade ago finally enabled us to pursue democratic reform in Central and Eastern Eu- rope and to lay the firm foundations of freedom, peace, and prosperity. -

Captive Nations Week” of the William J

The original documents are located in Box 34, folder “Captive Nations Week” of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 34 of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Captive Nations Week, 1975 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation The history of our Nation reminds us that the traditions of liberty must be protected and preserved by each generation. Let us, therefore, rededicate ourselves to . the ideals of our own democratic heritage. In so doing, we manifest our belief that all men everywhere have the same inherent right to freedom that we enjoy today. In support of this sentiment, the Eighty-sixth Congress, by a joint resolution approved July 17, 1959 (73 Stat. 212), authorized and requested the President to proclaim the third week in July of each year as Captive Nations Week. NOW, THEREFORE, I, GERALD R. -

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 5.20 OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE COMMISSIONS PARDONS, 1836- Abstract: Pardons (1836-2018), restorations of citizenship, and commutations for Missouri convicts. Extent: 66 cubic ft. (165 legal-size Hollinger boxes) Physical Description: Paper Location: MSA Stacks ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Alternative Formats: Microfilm (S95-S123) of the Pardon Papers, 1837-1909, was made before additions, interfiles, and merging of the series. Most of the unmicrofilmed material will be found from 1854-1876 (pardon certificates and presidential pardons from an unprocessed box) and 1892-1909 (formerly restorations of citizenship). Also, stray records found in the Senior Reference Archivist’s office from 1836-1920 in Box 164 and interfiles (bulk 1860) from 2 Hollinger boxes found in the stacks, a portion of which are in Box 164. Access Restrictions: Applications or petitions listing the social security numbers of living people are confidential and must be provided to patrons in an alternative format. At the discretion of the Senior Reference Archivist, some records from the Board of Probation and Parole may be restricted per RSMo 549.500. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain. Preferred Citation: [Name], [Date]; Pardons, 1836- ; Commissions; Office of Secretary of State, Record Group 5; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Acquisition Information: Agency transfer. PARDONS Processing Information: Processing done by various staff members and completed by Mary Kay Coker on October 30, 2007. Combined the series Pardon Papers and Restorations of Citizenship because the latter, especially in later years, contained a large proportion of pardons. The two series were split at 1910 but a later addition overlapped from 1892 to 1909 and these records were left in their respective boxes but listed chronologically in the finding aid.