Parameters of a Postcolonial Sociology of the Ottoman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Jules La Mission Civilisatrice, Le Bourguibism, and La Sécuritocratie

Current Issues in Comparative Education (CICE) Volume 22, Issue 1, Special Issue 2020 La Mission Civilisatrice, Le Bourguibism, and La Sécuritocratie: Deciphering Transitological Educational Codings in Post-spaces – the Case of Tunisia Tavis D. Jules Loyola University Chicago This article builds upon Robert Cowen’s (1996) work on educational coding in transitological settings and post-spaces by deciphering the efficacy of political and economic compressions in Tunisia from the French protectorate period to the 2011 post-Jasmine revolution. First, I diachronically decrypt and elucidate the specific experiences and trajectories of Tunisia’s transitologies, while paying attention to the emergence of specific synchronically educational moments. It is suggested that educational codes during transitory periods are framed by political compressions and preconceived philosophies of modernity. It is postulated that four educational codings can be derived in Tunisia’s post-spaces: (a) the protectorate code defined by la Mission Civilisatrice (the civilizing mission); (b) the post-protectorate code defined by le Bourguibisme (Bourguibism); (c) the post-Bourguibisme code defined by la Sécuritocratie (securitocracy) in the form of the national reconciliation; and (d) the post-Sécuritocratie period defined by the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) – as economic and political power is compressed into educational forms. I situate educational patterns within the Tunisian context to illustrate how educational codings shape post-spaces across these four transitory periods. Keywords: Tunisia, la Mission Civilisatrice, la Bourguibisme, la Securitocracy, transitology and educational codings. Introduction This paper employs Robert Cowen’s (2000) concept of “educational coding, that is, the compression of political and economic power into educational forms” (p. 10) within the context of transitologies (the study of transition) to reading the motor nuclei (a sequence of signposts that transcend discourse)1 of educational development across post-spaces. -

Marx and History: the Russian Road and the Myth of Historical Determinism

Ciências Sociais Unisinos 57(1):78-86, janeiro/abril 2021 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/csu.2021.57.1.07 Marx and history: the Russian road and the myth of historical determinism Marx e a história: a via russa e o mito do determinismo histórico Guilherme Nunes Pires1 [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to point out the limits of the historical determinism thesis in Marx’s thought by analyzing his writings on the Russian issue and the possibility of a “Russian road” to socialism. The perspective of historical determinism implies that Marx’s thought is supported by a unilinear view of social evolution, i.e. history is understood as a succes- sion of modes of production and their internal relations inexorably leading to a classless society. We argue that in letters and drafts on the Russian issue, Marx opposes to any attempt associate his thought with a deterministic conception of history. It is pointed out that Marx’s contact with the Russian populists in the 1880s provides textual ele- ments allowing to impose limits on the idea of historical determinism and the unilinear perspective in the historical process. Keywords: Marx. Historical Determinism. Unilinearity. Russian Road. Resumo O objetivo do presente artigo é apontar os limites da tese do determinismo histórico no pensamento de Marx, através da análise dos escritos sobre a questão russa e a possibilidade da “via russa” para o socialismo. A perspectiva do determinismo histórico compreende que o pensamento de Marx estaria amparado por uma visão unilinear da evolução social, ou seja, a história seria compreendida por uma sucessão de modos de produção e suas relações internas que inexoravelmente rumaria a uma sociedade sem classes sociais. -

Syntactic Changes in English Between the Seventeenth Century and The

I Syntactic Changes in English between the Seventeenth Century and the Twentieth Century as Represented in Two Literary Works: William Shakespeare's Play The Merchant of Venice and George Bernard Shaw's Play Arms and the Man التغيرات النحوية في اللغة اﻹنجليزية بين القرن السابع عشر و القرن العشرين ممثلة في عملين أدبيين : مسرحية تاجر البندقيه لوليام شكسبيرو مسرحية الرجل والسﻻح لجورج برنارد شو By Eman Mahmud Ayesh El-Abweni Supervised by Prof. Zakaria Ahmad Abuhamdia A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University January, 2018 II III IV Acknowledgments First and above all, the whole thanks and glory are for the Almighty Allah with His Mercy, who gave me the strength and fortitude to finish my thesis. I would like to express my trustworthy gratitude and appreciation for my supervisor Professor Zakaria Ahmad Abuhamdia for his unlimited guidance and supervision. I have been extremely proud to have a supervisor who appreciated my work and responded to my questions either face- to- face, via the phone calls or, SMS. Without his support my thesis, may not have been completed successfully. Also, I would like to thank the committee members for their comments and guidance. My deepest and great gratitude is due to my parents Mahmoud El-Abweni and Intisar El-Amayreh and my husband Amjad El-Amayreh who have supported and encouraged me to reach this stage. In addition, my appreciation is extended to my brothers Ayesh, Yousef and my sisters Saja and Noor for their support and care during this period, in addition to my beloved children Mohammad and Aded El-Rahman who have been a delight. -

ST2 : Penser Le Changement International Systemic Change

1 CONGRÈS AFSP STRASBOURG 2011 ST2 : Penser le changement international Golub, Philip American University of Paris (AUP) [email protected] Systemic Change Over Long Periods: East Asia’s Reemergence and the Two Waves of Globalization Synopsis: The re-emergence of East Asia and of other formerly peripheral world regions represents the most significant systemic transformation since the European industrial revolution. Wealth and power, long concentrated in a handful of states and a small fraction of the world population, is diffusing to post-colonial societies that have become, or are fast becoming, active units of the world system, shaping the global environment rather than simply being conditioned by it. As a result, we are witnessing a gradual but historically speaking rapid return to the conditions of pluralism and relative international equality that prevailed prior to the fracture between the “West and the rest” during the first wave of globalization in the nineteenth century. This paper examines systemic change over long periods and argues that the end of the long cycle of Euro-Atlantic ascendancy calls for a multidisciplinary rethinking of modernity to deal with the intellectual challenge posed. Keywords: globalization, core, periphery, empire, modernity Twenty years ago, when most American and European observers were focused on the end of the Cold War and celebrating the supposedly definitive ‘triumph’ of the West, Janet Abu-Lughod presciently anticipated the end of the era of “European/Western hegemony” and a “return to the relative balance of multiple centers” that preceded the age of western empire and industry. [Abu-Lughod, 1991, 370-371] Since then, the movement towards a polycentric systemic configuration has quickened rather dramatically as various postcolonial countries have exited the periphery and consolidated their emergent position as growth centers of the world capitalist economy. -

Why (Post)Colonialism and (De)Coloniality Are Not Enough: a Post- Imperialist Perspective Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Available Online: 07 Oct 2011

This article was downloaded by: [Gustavo Lins Ribeiro] On: 21 October 2011, At: 17:44 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Postcolonial Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cpcs20 Why (post)colonialism and (de)coloniality are not enough: a post- imperialist perspective Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Available online: 07 Oct 2011 To cite this article: Gustavo Lins Ribeiro (2011): Why (post)colonialism and (de)coloniality are not enough: a post-imperialist perspective, Postcolonial Studies, 14:3, 285-297 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2011.613107 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 285Á297, 2011 Why (post)colonialism and (de)coloniality are not enough: a post-imperialist perspective GUSTAVO LINS RIBEIRO The need to examine knowledge production in relation to location and subject position is a consolidated trend in several theoretical approaches. -

Angus Taylor Perhaps the Most Influential Critique of Marx's Theory

Angus Taylor Flogging a Straw Man: Popper's Critique of Marx's "Historicism" Perhaps the most influential critique of Marx's theory of history has been that by Karl Popper, considered by some to be the foremost philosopher of science. It is Popper's contention that while Marx's stress on economic and technological factors in the evolution of socie ties has been salutary, Marx's theory of history is fatally flawed by being based on the idea of historical determinism. In opposition, Popper wishes to assert the vital role of human creativity and rational agency in history. But is his critique well founded? It is my contention that while Popper may be correct in denouncing historical determin ism as fundamentally erroneous, his belief that Marx's theory of history embodies this concept is itself erroneous. Popper maintains that the course of human history cannot be the subject of scientific investigation, at least insofar as such investigation involves prediction. He thus sets about to refute what he calls the doctrine of historicism, by which he means "an approach to the social sciences which assumes that historical prediction is their principal aim, and which assumes that this aim is attainable by discovering the 'rhythms' or the 'patterns', the 'laws' or the 'trends' that underlie the evolution of history."t Historicism, as he conceives it, teaches that the course of history is, at least in broad outlines, predetermined. Popper argues that the course of history is strongly influenced by the growth of knowledge, and that it is impossible to predict our future states of knowledge (for we cannot know today what we shall only discover tomorrow). -

Beyond the “Postmodern University”*

Beyond the “Postmodern University”* Claire Donovan Abstract As an institution, the “postmodern university” is central to the canon of today’s research on higher education policy. Yet in this essay I argue that the postmodern university is a fiction that frames and inhibits our thinking about the future university. To understand why the postmodern university is a fiction, I first turn to grand theory and ask whether we can make sense of the notion of “post”-postmodernity. Second, I turn to the UK higher education sector and show that the postmodern university is a chimera, a modern artefact of competing instrumentalist, gothic, and postmodernist discourses. Third, I discuss competing visions of the future university and find that the progressive (yet modernist) agendas that re-imagine the public value of knowledge production, transmission, and contestation, are those that can move us beyond the palliative and panacea of the postmodern university. * Health Economics Research Group, Brunel University, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK. Email: [email protected]. 1 In this essay I investigate the idea of the postmodern university, an institution that is central to research on, and debate about, higher education policy.1 I contend that the postmodern university does not actually exist, yet this fiction casts a shadow over discussions of higher education policy that inhibits more lateral and creative thinking about the future university. In order to properly investigate the concept of the postmodern, it is first necessary to explain the difference between postmodernism and postmodernity. I then ask if we can make sense of being “beyond” postmodernity to prove that postmodernity has never, in fact, existed. -

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Georg Lukács and Organizing Class Consciousness / by Robert Lanning

Georg Lukács and Organizing Class Consciousness Georg Lukács and Organizing Class Consciousness by Robert Lanning MEP Publications MEP Publications University of Minnesota 116 Church Street S.E. Minneapolis, MN 55455-0112 Copyright © 2009 by Robert Lanning All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lanning, Robert. Georg Lukács and organizing class consciousness / by Robert Lanning. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-930656-77-5 1. Lukács, György, 1885-1971--Criticism and interpretation. 2. Philosophy, Marxist. 3. Social conflict. 4. Class consciousness. I. Title. B4815.L84L36 2009 335.4’11 -- dc22 2009015114 CONTENTS Chapter One Class Consciousness and Reification 1 Chapter Two Historical Necessity as Self-Activity 31 Chapter Three The Concept of Imputed Class Consciousness 55 Chapter Four Common Sense and Market Rationality in Sociological Studies of Class 77 Chapter Five Being Determines Consciousness 109 Chapter Six Consciousness Overemphasized? 125 Chapter Seven Class Experience, “Substitution,” and False Consciousness 143 Chapter Eight Imputed Class Consciousness in the Development of the Individual 165 Conclusion 193 Reference List 197 Index 205 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank David S. Pena for his thorough editing of the manuscript, and Erwin and Doris Grieser Marquit for seeing this project through its stages of development. I would also like to acknowledge Erwin’s editing of twenty volumes of Nature, Society, and Thought (1987–2007), a journal that exhibited an important balance between politics and scholarship. Chapter One Class Consciousness and Reification To be scientific, sociologists must ask not merely what some member of a social group thinks today about refrigerators and gadgets or about marriage and sexual life, but what is the field of consciousness within which some group can vary its ways of thinking about all these problems. -

Migrations' European History Maps

Worksheet Migrations’ European History Maps Atlas of European history - Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/.../Atlas_of... Historical maps of the Iberian Peninsula - Visigoth migrations.jpg ... Map Almoravid empire-en.svg ... Almoravid map reconquest loc.jpg ... European History Interactive Map - Worldology www.worldology.com/Europe/europe_history_lg.htm My aim was merely to show a broad-brushed evolution of European history. ...... It's a fun and interactive way to learn more about history and migration patterns. Genetic history maps centuries of European migration | University of ... www.ox.ac.uk/.../2015-09-18-genetic-histo... Genetics researchers at the University of Oxford have used DNA to map the history of population movements in and around Europe. History of Europe (3000 BC - 2013 AD) - YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l53bmKYXliA Source: http://geacron.com/home-en/ - the best historical atlas i ever seen Music: Globus - Crusaders of the … 4 maps that will change how you see migration in Europe | World ... https://www.weforum.org/.../these-4-maps-... 4 maps that will change how you see migration in Europe. Migrant children ... Climate and clams: 500 years of history in one shell. Ian Hall ... Maps of Neolithic, Bronze Age & Iron Age migrations in Europe and ... www.eupedia.com › Genetics Maps of Neolithic & Bronze Age migrations around Europe ... History of R1b from the Ice Age origins until the beginning of the Hallstatt period (1200 BCE). Migrations Map: Where are migrants coming from? Where have ... migrationsmap.net/ Where are migrants coming from? Where have migrants left? Click on the map or pick a country here: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, American Samoa, Andorra .. -

![54. Late Modern English: Syntax [Draft Version, June 2011]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0379/54-late-modern-english-syntax-draft-version-june-2011-1460379.webp)

54. Late Modern English: Syntax [Draft Version, June 2011]

54. Late Modern English: Syntax [draft version, June 2011] Bas Aarts, Maria José López -Couso and Bel én Méndez- Naya 1. Introduction 2. Categorical innovations of the Late Modern English period 3. Statistical and regulatory changes 4. Concluding remarks Abstract The Late Modern English period provides an essential link between the synta ctic innovations of Early Modern English and the established system of Present-day English. This chapter reviews a number of major syntactic developments taking place in the period, involving both categorical and statistical changes. Among the former, we discuss two important innovations in the domain of voice: the rise of the progressive passive, with its implications for the symmetry of the auxiliary system, and the emergence and consolidation of the get -passive. The 18th and 19th centuries also see the completion and/or regulation of long -term tendencies in various areas of syntax, such as the verb phrase (the consolidation of the progressive, the decline of the be-perfect and the regulation of periphrastic do), and subordination (changes in the complemen tation system, in particular the replacement of the to -infinitive by -ing complements, and in relative clauses, with the regulation of the distribution of the different relativizers). 1. Introduction The Late Modern English period has received much less scholarly attention than earlier stages in the history of English, partly because of its closeness to the present day and its apparent similarity to the contemporary language. This neglect has been particularly noticeable in the case of syntax. It is a we ll -known fact that the most substantive syntactic changes in the history of English had already taken place when our period opened, the 18 th and 19th centuries representing mainly a transitional stage between the categorical innovations of Late Middle Engl ish and, especially, Early Modern English and the “established” system of Present-day English. -

Handbook Global History 2014

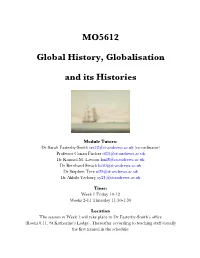

MO5612 Global History, Globalisation and its Histories Module Tutors: Dr Sarah Easterby-Smith [email protected] (co-ordinator) Professor Conan Fischer [email protected] Dr Konrad M. Lawson [email protected] Dr Bernhard Struck [email protected] Dr Stephen Tyre [email protected] Dr Akhila Yechury [email protected] Time: Week 1 Friday 10-12 Weeks 2-11 Thursday 11:30-1:30 Location The session in Week 1 will take place in Dr Easterby-Smith’s office (Room 0.11, St Katharine’s Lodge). Thereafter according to teaching staff (usually the first named in the schedule) Description Over the past two decades or so global history, along with world history and the history of globalisation has become one of the most vibrant fields in history – and in modern history in particular. Global history can broadly be defined as the analysis of flows and interconnections of people, goods, commodities, or ideas through, across and between continents, cultures, countries and borders. This module is designed as a broad introductory module to the field of global history, its methods, approaches and recent historiographical trends, from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. It follows a problem and theme oriented structure rather than a chronological order. The first sessions examine recent trends that have contributed to the emergence of global history as well as related concepts such as transnational history. We will discuss distinct fields and schools, including the historiographies on globalization, transnationalism and postcolonial studies. Following this the course engages with alternative spaces and various scales in global history, namely oceans, empires, metropolises and the question of territoriality and sovereignty.