Edward Downes: a Life in Music and the Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Time 1925 1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Giulio Gatti Casazza 1926 Director, Metropolitan Opera Arturo Toscanini Leopold Stokowski 1926 1930 Conductor Conductor Pietro Mascagni Lucrezia Bori James Cæsar Petrillo 1926 1930 1948 Composer Singer Head, American Federation of Musicians Richard Strauss Alfred Hertz Sergei Koussevitsky Helen Traubel Charles Munch 1938 1927 1930 1946 1949 Composer and conductor Conductor Conductor Singer Conductor Ignace J Paderewski Geraldine Farrar Joseph Deems Taylor Marian Anderson Cole Porter 1939 1927 1931 1946 1949 Kirsten Flagstad Pianist, politician Singer Composer, critic Singer Composer 1935 Lauritz Melchior Giulio Gatti-Casazza Ignace Jan Paderewski Yehudi Menuhin Singer Artur Rodziński Gian Carlo Menotti Maria Callas 1940 1923 1928 1932 1947 1950 1956 Artur Rubinstein Edward Johnson Singer Director, Metropolitan Opera Pianist, politician Violinist; 16 years old Conductor Composer Singer 1966 1936 Leopold Stokowski Pianist Johann Sebastian Bach Nellie Melba Mary Garden Lawrence Tibbett Singer Arturo Toscanini Mario Lanza & Enrico Caruso Leonard Bernstein 1940 1968 1927 1930 1933 1948 1951 1957 Jean Sibelius Conductor Dmitri Shostakovich Composer (1685–1750) Singer Singer Singer Conductor Singers Composer, conductor 1937 1942 Beverly Sills Richard Strauss Rosa Ponselle Arturo Toscanini Composer Composer Benjamin Britten Patrice Munsel Renata Tebaldi Rudolf Bing Luciano Pavarotti 1971 1927 1931 1934 1948 1951 1958 1966 1979 Sergei Koussevitsky Sir Thomas Beecham Leontyne Price Singer Georg Solti Composer, conductor Singer Conductor Composer -

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR of DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY and GROWTH the METROPOLITAN OPERA New York, New York the Metropolitan Opera

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND GROWTH THE METROPOLITAN OPERA New York, New York The Metropolitan Opera The Aspen Leadership Group is proud to partner with The Metropolitan Opera in the search for an Executive Director of Development Strategy and Growth. The Executive Director will work in close partnership with the Assistant General Manager, Development, and will be responsible for identifying and implementing strategies for growth in contributed revenue. Areas of focus in 2019 and 2020 will include national and global corporate partnerships, planned giving, and international fundraising. The Executive Director will manage staff and projects as assigned by the Assistant General Manager and as appropriate to each growth strategy. REPORTING RELATIONSHIPS The Executive Director of Development Strategy and Growth will report to the Assistant General Manager, Development. PRINCIPAL OPPORTUNITIES The Met’s audience is global and includes millions of devoted viewers and listeners. This reach positions the Met for corporate partnerships at the highest levels, with significant growth opportunity. The Met is also uniquely positioned to reach and remain relevant to audience members until the very end of their lives, presenting an extraordinary opportunity for growth in planned giving. This global reach, combined with the growth of philanthropy in other countries, presents an additional opportunity for enhanced revenue from international sources. The Met has one of the strongest individual giving programs in the country, rivaling and surpassing the levels of giving and donor engagement seen in many major universities and health care centers. Its core audience is deeply and passionately devoted to the art form. The Executive Director will have the opportunity to build upon this strong foundation, immediately expanding revenue generation in identified areas with untapped potential. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

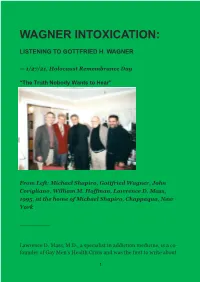

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Berliner Philharmoniker

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director November 12–13, 2016 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert I Saturday, November 12, 8:00 pm 3 Concert II Sunday, November 13, 4:00 pm 15 Artists 31 Berliner Philharmoniker Concert I Sir Simon Rattle Artistic Director Saturday Evening, November 12, 2016 at 8:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 14th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the Eugene and Emily Grant Family Foundation. This evening’s supporting sponsor is the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. This evening’s performance is funded in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s performance is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of lobby floral art for this evening’s performance. Special thanks to Bill Lutes for speaking at this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Journeys International, sponsor of this evening’s Prelude Dinner. Special thanks to Aaron Dworkin, Melody Racine, Emily Avers, Paul Feeny, Jeffrey Lyman, Danielle Belen, Kenneth Kiesler, Nancy Ambrose King, Richard Aaron, and the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance for their support and participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Deutsche Bank is proud to support the Berliner Philharmoniker. Please visit the Digital Concert Hall of the Berliner Philharmoniker at www.digitalconcerthall.com. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 31,1911-1912, Trip

ACADEMY OF MUSIC . BROOKLYN Thirty-first Season, J9U-J9I2 Soaimt Symphony t§tttymm MAX FIEDLER, Conductor frogramm? of % FOURTH CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 23 AT 8.15 . COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER ha6> MIGNONETTE GRAND In Fancy $700 Mahogany 5 feet 2 inches Where others have failed to build a Small and Perfect Grand Piano meeting with present-day requirements, the House of Knabe, after years of research and experiment, has succeeded in producing The World's Best Grand Piano as attested by many of the World's best musicians, grand opera artists, stars, composers, etc. The Knabe Mignonette Grand is indispensable where space is limited— desirable in the highest degree where an abundance of space exists. Wm. KNABE & Co. Division—American Piano Co. 5th Avenue and 39th Street - - NEW YORK CITY Established 1837 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirty-first Season, 1911-1912 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Theodorowicz, J. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Krafft, F. W. Mahn, F. Noack, S. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Goldstein, H. Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Marble, E. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H. Kurth, R. Fabrizio, C. i Goldstein. S. Werner, H. Griinberg, M. Violas. Ferir, E. Spoor, S. Pauer, H. Kolster, A. VanWynbergen, C Gietzen, A. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M '.. Forster, E. Kautzenbach, W. Violoncellos. Schroeder, A. Keller, Belinski, J. Barth , C. M Warnke, J. -

1St Connection Between Baseball and Opera

Baseball & Opera (compiled by Mark Schubin, this version posted 2014 April 14) 1849 : 1 st connection between baseball and opera: Fans of American actor Edwin Forrest, who is playing Macbeth in New York, hire thugs from among ballplayers at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey (1 st famous ball field) to disrupt performances of British actor William Macready, also playing Macbeth in New York at what had been Astor Opera House. Deadly riot ensues; Macready is rescued by ex-Astor Opera House impresario Edward Fry, who later (1880) invents electronic home entertainment (and probably headphones) by listening to live opera by phone. 1852: Opera-house exclusivity dispute with composer’s niece Johanna Wagner forms legal basis of baseball’s reserve clause. 1870 : Tony Pastor’s Opera House baseball team is covered by The New York Times (they won). 1875 : San Francisco Chronicle reports on that city’s opera-house baseball team. 1879 : Pirate King role created for Signor Brocolini, who, as John Clark, played first base for the Detroit Base Ball Club. 1881 : Dartmouth College opera group performs to raise money for college’s baseball team. 1884 : Three telegraph operators, James U. Rust, E. W. Morgan, and A. H. Stewart, present live games remotely. One sends plays from ballpark, second receives and announces, third moves cards with players’ names around backdrop. Starting in Nashville’s 900-seat Masonic Theater, they soon move to 2,500-seat Grand Opera House, beginning half-century of remote baseball game viewing at opera houses (also Augusta, GA Grand Opera House starting 1885). 1885 : The Black Hussar is probably 1 st opera with baseball mentioned in its libretto (in “Read the answer in the stars”). -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Documented , Two Files in 32 Parts Introduction to Securing My Traces

My archive ( 225 boxes / moving boxes ) , documented , two files in 32 parts Introduction to securing my traces : 35 pages with photos – as of 4th December, 2020 Securing my traces – first file – 1st to 16th part Motto: “Tell me what you are looking for and I will tell you who you are “ cf. www.gottfriedhwagner.eu – with 26 films – GWA ZBZ 1st part: my school education, secondary education, my time at university. My work in direction, dramaturgies— Kurt Weill – 22 pages 2nd part: My way to Kurt Weill - Lotte Lenya – my Weill and Brecht book - 3 pages 3rd part: my short biography - Ralph Giordano on me - 3 pages 4th part : my themes and stages from 1953 up to 2021 - 56 pages 5th part: survey of the contents of my 225 moving boxes/ boxes - 13 pages – as of 04.12.2020 6th part: My Post Shoah Dialog with Abraham J. Peck [GHW-AJP] - 2 pages 7th part: Our Zero Hour– the joint book [GHW AJP] - 19 pages 8th part : Content of Our Zero Hour [GHW-AJP] - 10 pages 9th part : My post Shoah Dialog with the composer Janice Hamer - 17 pages 10th part: My notes on the Tel Aviv performance of Lost Childhood - 4 pages 11th part: My Shoah and Post Shoah work in box 13 to box 40 - 98 pages 12th part: Richard Wagner and consequences – My dark “Wagner legacy” - 80 pages 13th part: My experiences with the 2nd and 3rd Wagner clan generations - 64 pages * 14th part: From Wagner to Hitler and New Bayreuth: The conflict with my father Wolfgang and grandmother Winifred Wagner and their connections – Wolfgang Wagner - 86 pages * 15th part: My indemnity and my father’s revenge, his lawyers: - 36 pages * 16th part: My discussions with my aunts: Gertrud Wagner and Verena Lafferentz-Wagner-13 pages* ”Second File – Securing my traces: 17.