Oliver Cromwell, the Regicide and the Sons of Zeruiah John Morrill and Philip Baker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[1529] Rolls of Parl](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4120/1529-rolls-of-parl-94120.webp)

[1529] Rolls of Parl

1 From Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, vol. 4: 1524-30, edited by J. S. Brewer. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Offi ce, 1875, pp. 2689-93. 3 Nov. [1529] 6043. P. Rolls of Parl. Begun at the Black Friars, London, 3 Nov. 21 Hen. VIII., the King being present the fi rst day. Sir Thos. More as chancellor declared the cause of its being summoned,1 viz., to reform such things as have been used or permitted in England by inadvertence, or by the changes of time have become inexpedient, and to make new statutes and laws where it is thought fi t. On these errors and abuses he discoursed in a long and elegant speech, declaring with great eloquence what was needful for their reformation, and in the end he ordered the Commons in the King’s name to assemble next day in their accustomed house and choose a Speaker, whom they should present to the King. That grievances might be examined, receivers and triers of petitions were appointed for the present Parliament, whose names were read out in French by the clerk of the Parliaments in the usual fashion. Receivers of petitions from England, Ireland, Wales, and Scotland:—Sir John Taillour, Sir Will. Knyght, Sir John Wolman, Sir Roger Lupton. Of Gascony and parts beyond sea:—Sir Steph. Gardiner, Sir Jo. Throkmerton, Sir Thos. Newman. [2690] Tr iers of petitions from England, Ireland, Wales, and Scotland:—The archbishop of Canterbury, the dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, the marquises of Dorset and Exeter, the bishop of London, the earl of Shrewsbury, viscounts Lisle, Fitzwater, and Rocheford, the abbot of Westminster, and Sir John FitzJames. -

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugu rated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia. REVOLUTION GOES EAST Imperial Japan and Soviet Communism Tatiana Linkhoeva CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of New York University. Learn more at the TOME website, which can be found at the following web address: openmono graphs.org. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International: https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress. cornell.edu. Copyright © 2020 by Cornell University First published 2020 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Linkhoeva, Tatiana, 1979– author. Title: Revolution goes east : imperial Japan and Soviet communism / Tatiana Linkhoeva. Description: Ithaca [New York] : Cornell University Press, 2020. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019020874 (print) | LCCN 2019980700 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501748080 (pbk) | ISBN 9781501748097 (epub) | ISBN 9781501748103 (pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Communism—Japan—History—20th century. -

The English Republic

72 The English Republic DOROTHY THOMPSON By the second half of the eighteenth century, England must have seemed the European country most likely to dispense with monarchical and aristo- cratic government. English kings had been by-passed, dethroned, even decapitated for the protection of the protestant faith and the sanctity of parliamentary government. Legitmacy in English monarchs came second to adhesion to acceptable political and religious views. The ruling house of Hanover was unpopular with many sections of the populace, a populace notorious for its and unruly and levelling behaviour. A cheap and expanding press fed a sophisticated and organised public opinion among the lower orders. In 1779 increasing concern with political and clerical authority errupted into major riots against catholic relief and against the refusal of parliament to modify the relief bill in response to mass petitioning. The riots, which took the name of the instigator of the petitions, Lord George Gordon, also took in attacks on poll booths and prisons, the symbols of state power. Two hundred people perished in the military confrontation by which the rioters were brought to heel, and other European states, particularly France, where central control and policing were more powerful, looked on in horror. By the opening of the twentieth century, however, the death of a monarch brought hundreds of thousands of mourners into the streets in England, and by the close of that century Britain was one among a group of north European countries in which a stable democracy existed under a monarchical system. It is one of the curious aspects of British history that there has not been in England, at least since the seventeenth century, a republican party. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

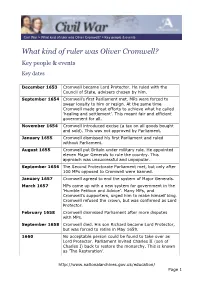

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Bookshelf 2015 Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity Kristin M.S. Bezio University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/bookshelf Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bezio, Kristin M.S. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015. NOTE: This PDF preview of Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays: History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignity includes only the preface and/or introduction. To purchase the full text, please click here. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bookshelf by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Power in Tudor and Stuart English History Plays History, Political Thought, and the Redefinition of Sovereignty KRISTIN M.S. BEZIO University ofRichmond, USA LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA 23173 ASHGATE Introduction Of Parliaments and Kings: The Origins of Monarchy and the Sovereign-Subject Compact in the English Middle Ages (to 1400) The purpose of this study is to examine the intersection between early modem political thought, the history that produced the late Tudor and early Stuart monarchies, and the critical interrogation of both taking place on the public theatrical stage. The plays I examine here are those which rely on chronicle histories for their source materials; are set in England, Scotland, or Wales; focus primarily on governance and sovereignty; and whose interest in history is didactic and actively political. -

Republicanism in Nineteenth Century England

NORBERT J. GOSSMAN REPUBLICANISM IN NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND To one familiar with the attitude of "near devotion" accorded the monarchy by the majority of Englishmen today, it may come as a shock to discover a lack of this devotion in mid-Victorian England. A sampling of comments from the radical press is a striking example. Trie-regular arrival of Victoria's progeny evoked this impious sug gestion in the Northern Star: That, rather than reciting national prayers of thanksgiving, congregations should sing "hymns of despair for their misfortune in being saddled with another addition to the brood of royal Cormorants." 1 The National Reformer referred to "our good kind, and dear Queen, who... could easily dispense with the allowance which her loyal subjects make her... unless she desires to be the last of England's monarchs..." 2 Yet criticism of Victoria was mild in comparison with the criticism directed toward her immediate predecessors. Upon the death of George IV in June 1830, the Times had the following comment: "The truth is... that there never was an individual less regretted by his fellow- creatures than this deceased King... If George IV ever had a friend, a devoted friend - in any rank of life - we protest that the name of him or her has not yet reached us." 3 This attitude toward the monarchy can be explained partly by the personalities of some of the Hanoverians - George IV, for example, 4 partly by objections to the growing expense of monarchy, but it might also be explained by the feeling in some radical circles that the institution of monarchy was incompatible with the growth of demo cracy. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Crucibles of Virtue and Vice: the Acculturation of Transatlantic Army Officers, 1815-1945

CRUCIBLES OF VIRTUE AND VICE: THE ACCULTURATION OF TRANSATLANTIC ARMY OFFICERS, 1815-1945 John F. Morris Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 John F. Morris All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Crucibles of Virtue and Vice: The Acculturation of Transatlantic Army Officers, 1815-1945 John F. Morris Throughout the long nineteenth century, the European Great Powers and, after 1865, the United States competed for global dominance, and they regularly used their armies to do so. While many historians have commented on the culture of these armies’ officer corps, few have looked to the acculturation process itself that occurred at secondary schools and academies for future officers, and even fewer have compared different formative systems. In this study, I home in on three distinct models of officer acculturation—the British public schools, the monarchical cadet schools in Imperial Germany, Austria, and Russia, and the US Military Academy—which instilled the shared and recursive sets of values and behaviors that constituted European and American officer cultures. Specifically, I examine not the curricula, policies, and structures of the schools but the subterranean practices, rituals, and codes therein. What were they, how and why did they develop and change over time, which values did they transmit and which behaviors did they perpetuate, how do these relate to nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century social and cultural phenomena, and what sort of ethos did they produce among transatlantic army officers? Drawing on a wide array of sources in three languages, including archival material, official publications, letters and memoirs, and contemporary nonfiction and fiction, I have painted a highly detailed picture of subterranean life at the institutions in this study. -

CAN WORDS PRODUCE ORDER? Regicide in the Confucian Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lirias CAN WORDS PRODUCE ORDER? Regicide in the Confucian Tradition CARINE DEFOORT KU Leuven, Belgium ᭛ ABSTRACT This article presents and evaluates a dominant traditional Chinese trust in language as an efficient tool to promote social and political order. It focuses on the term shi (regicide or parricide) in the Annals (Chunqiu). This is not only the oldest text (from 722–481 BCE) regularly using this term, but its choice of words has also been considered the oldest and most exemplary instance of the normative power of language. A close study of its uses of ‘regi- cide’ leads to a position between the traditional ‘praise and blame’ theory and its extreme negation. Later commentaries on the Annals and reflection on regicide in other texts, in different ways, attest to a growing reliance or belief in the power of words in the political realm. Key Words ᭛ Annals (Chunqiu) ᭛ China ᭛ language ᭛ order ᭛ regicide Two prominent scholars hold a debate in front of Emperor Jing (156–41 BCE). One of them is Master Huang, a follower of Huang Lao and the teachings of ‘The Yellow Emperor and Laozi’. The other is Master Yuan Gu, a specialist in the Book of Odes and appointed as erudite at the court of Emperor Jing. Master Huang launches the discussion with the provoca- tive claim that Tang and Wu, the founding fathers of China’s two exem- plary dynasties, respectively the Shang (18th–11th century) and Zhou (11th–3rd century) dynasties, were guilty of regicide against Jie and Zhòu, the last kings of the preceding dynasties. -

The Social Impact of the Revolution

THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE'S DISTINGUISHED LECTURE SERIES Robert Nisbet, historical sociologist and intellectual historian, is Albert Schweitzer professor-elect o[ the humanities at Columbia University. ROBERTA. NISBET THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION Distinguished Lecture Series on the Bicentennial This lecture is one in a series sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute in celebration of the Bicentennial of the United States. The views expressed are those of the lecturers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff,officers or trustees of AEI. All of the lectures in this series will be collected later in a single volume. revolution · continuity · promise ROBERTA. NISBET THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF THE REVOLUTION Delivered in Gaston Hall, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. on December 13, 1973 American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research Washington, D.C. © 1974 by American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-8447-1303-1 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number L.C. 74-77313 Printed in the United States of America as there in fact an American Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century? I mean a revolu tion involving sudden, decisive, and irreversible changes in social institutions, groups, and traditions, in addition to the war of libera tion from England that we are more likely to celebrate. Clearly, this is a question that generates much controversy. There are scholars whose answer to the question is strongly nega tive, and others whose affirmativeanswer is equally strong. Indeed, ever since Edmund Burke's time there have been students to de clare that revolution in any precise sense of the word did not take place-that in substance the American Revolution was no more than a group of Englishmen fighting on distant shores for tradi tionally English political rights against a government that had sought to exploit and tyrannize. -

The Levellers' Conception of Legitimate Authority

Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades ISSN: 1575-6823 ISSN: 2340-2199 [email protected] Universidad de Sevilla España The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Ostrensky, Eunice The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. 20, no. 39, 2018 Universidad de Sevilla, España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28264625008 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative e Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority A Concepção de Autoridade Legítima dos Levellers Eunice Ostrensky [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo, Brasil Abstract: is article examines the Levellers’ doctrine of legitimate authority, by showing how it emerged as a critique of theories of absolute sovereignty. For the Levellers, any arbitrary power is tyrannical, insofar as it reduces human beings to an unnatural condition. Legitimate authority is necessarily founded on the people, who creates the constitutional order and remains the locus of political power. e Levellers also contend that parliamentary representation is not the only mechanism by which the people may acquire a political being; rather the people outside Parliament are the collective agent able to transform and control institutions and policies. In this sense, the Levellers hold that a highly participative community should exert sovereignty, and that decentralized government is a means to achieve that goal. Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Keywords: Limited Sovereignty, Constitution, People, Law, Rights. Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. Resumo: Este artigo analisa como os Levellers desenvolveram uma doutrina da 20, no.