Maternal Mortality Estimation at the Subnational Level: a Model Based Method with an Application to Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhd Road Network, Rangpur Zone

RHD ROAD NETWORK, RANGPUR ZONE Banglabandha 5 N Tentulia Nijbari N 5 Z 5 0 6 Burimari 0 INDIA Patgram Panchagarh Z Mirgarh 5 9 0 Angorpota 3 1 0 0 5 Z Dhagram Bhaulaganj Chilahati Atwari Z 57 Z 06 5 0 Kolonihat Boda 2 1 Tunirhat Gomnati 3 0 Dhaldanga 7 Ruhea Z 5 N 6 5 Z 5 0 0 Dimla 0 0 2 3 7 9 2 5 6 Z 54 INDIA 5 Debiganj Z50 Sardarhat Z 9 5 0 5 5 Domar Hatibanda Bhurungamari Baliadangi Z N Kathuria Boragarihat Z5 Bahadur Dragha 002 2 Z5 0 7 0 03 5 Thakurgaon Z RLY 7 R 0 Station 58 2 7 7 Jaldhaka 2 5 Bus 6 Dharmagarh Stand Z 5 1 Z Z5 70 029 Z5 Nekmand Z Mogalhat 5 Kaliganj 6 Z5 Tengonmari 17 Nageshwari 2 7 56 4 7 Z 2 09 1 Raninagar Kadamtala 0 Z 0 0 57 5 9 0 Z 0 5 Phulbari Z 5 5 2 Z 5 5 Z Namorihat 0 Kalibari 2 Khansama 16 6 5 56 Z 2 Z Z Aditmari 01 Madarganj 50 Z5018 N509 Z59 4 Ranisonkail N5 08 Tebaria Nilphamari Kishoreganj 8 Z5 Kutubpur 00 008 Lalmonirhat Bhitarbond Z5 Z 2 Z5018 Z5018 Shaptibari 5 2 6 4 Darwani Z 2 6 0 1 0 5 Manthanahat 5 R Z5 Z 9 6 Z 0 00 Pirganj Bakultala 0 Barabari 5 2 5 5 5 1 0 Z Z Z Z5002 7 5 5 Z5002 Birganj 0 0 02 Gangachara N 5 0 5 Moshaldangi Z5020 06 6 06 0 5 0 N 5 Haragach Haripur Z 7 0 N5 Habumorh Bochaganj 0 5 4 Z 2 Z5 61 3 6 5 1 11 Z 5 Taraganj 2 6 Kurigram 0 N Hazirhat 5 Kaharol 5 Teesta 18 Z N5 Ranirbandar N5 Z Kaunia Bridge Rajarhat Z Saidpur Rangpur Shahebganj 5 Beldanga 0 Medical 0 5 Shapla 6 1 more 1 1 more 0 0 5 5 25 Ghagat Z 50 N517 Z Z Bridge Taxerhat N5 Mohiganj 1 2 Mordern 6 4 more 5 02 Z 8 5 Z Shampur 0 Modhupur Z 5 Parbatipur 50 N Sonapukur Badarganj 1 Chirirbandar Z5025 0 Ulipur Datbanga Govt Z5025 Pirgachha College R 5025 Simultala Laldangi 5 Z Kolahat Z 8 Kadamtali Biral Cantt. -

12578ESIA Report Narayanganj Silo.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLES' REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH MINISTRY OF FOOD DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF FOOD MODERN FOOD STORAGE FACILITIES PROJECT (MFSP) IDA Credit # 5265-BD ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) REPORT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF GALVANIZED CORRUGATED FLAT BOTTOM STEEL SILO WITH RCC FOUNDATION AND IT'S ANCILLARY WORKS AT NARAYANGANJ SILO SITE PROJECT DIRECTOR MODERN FOOD STORAGE FACILITIES PROJECT PROBASHI KALLAYAN BHABAN, 71-72, ESKATON GARDEN RAMNA, DHAKA-1000, BANGLADESH. OCTOBER, 2019 Modern Food Storage Facilities Project (MFSP), Narayanganj Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................... vi ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... ix 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Objectives of the Project ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 Strategic Objectives ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.2 Specific Objectives ............................................................................................. -

46399E642.Pdf

PGDS in DOS Myanmar Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of January 2006 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ((( Yüeh-hsi ((( ((( Zayü ((( ((( BANGLADESHBANGLADESH ((( Xichang ((( Zhongdian ((( Ho-pien-tsun Cox'sCox's BazarBazar ((( ((( ((( ((( Dibrugrh ((( ((( ((( (((Meiyu ((( Dechang THIMPHUTHIMPHU ((( ((( ((( Myanmar_Atlas_A3PC.WOR ((( Ningnan ((( ((( Qiaojia ((( Dayan ((( Yongsheng KutupalongKutupalong ((( Huili ((( ((( Golaghat ((( Jianchuan ((( Huize ((( ((( ((( Cooch Behar ((( North Gauhati Nowgong (((( ((( Goalpara (((( Gauhati MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( Dinhata ((( ((( Gauripur ((( Dongch ((( ((( ((( Dengchuan ((( Longjie ((( Lalmanir Hat ((( Yanfeng ((( Rangpur ((( ((( ((( ((( Yuanmou ((( Yangbi((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Shillong ((((( Xundia ((( ((( Hai-tzu-hsin ((( Yongping ((( Xiangyun ((( ((( ((( Myitkyina ((( ((( ((( Heijing ((( Gaibanda NayaparaNayapara ((((( ((( (Sha-chiao(( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yipinglang ((( Baoshan TeknafTeknaf ButhidaungButhidaung (((TeknafTeknaf ((( ((( Nanjian ((( !! ((( Tengchong KanyinKanyin((( ChaungChaung !! Kunming ((( ((( ((( Anning ((( ((( ((( Changning MaungdawMaungdaw ((( MaungdawMaungdaw ((( ((( Imphal Mymensingh ((( ((( ((( ((( Jiuyingjiang ((( ((( Longling 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yunxian ((( ((( ((( ((( -

News Literacy in Bangladesh National Survey News Literacy in Bangladesh National Survey

News Literacy in Bangladesh National Survey News Literacy in Bangladesh National Survey LEAD RESEARCHER AND AUTHOR MD Saiful Alam Chowdhury Associate Professor, Department of Mass Communication & Journalism, Dhaka University FIELD SURVEY Reslnt Bangladesh an affiliate of ResInt Canada RESEARCH TEAM Ala Alizan Hossain Programme Officer, MRDI Modina Jahan Rime Media Monitoring Officer, Promoting News Literacy and Ethical Journalism, project, MRDI © Management and Resources Development Initiative (MRDI) Published : 2020 ISBN : 978-984-34-8284-6 Management and Resources Development Initiative 8/19, Sir Syed Road (3rd Floor), Block-A, Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone : +880-2-9134717, +880-2-9137147 , Fax : +880-2-9134717, +880-2-9137147 Ext-111 E-mail : [email protected], Web : www.mrdibd.org FOREWORD We are living in an age awash in news, news that are used to make critical decisions in all aspects of our lives: in education, government, economics, public safety, politics, international development, health care, marketing and more. People today have access to more information than any generation in history, yet many lack the knowledge and critical-thinking skills needed to navigate our challenging information ecosystem. The potential for misinformation has never been greater, and the concept of news literacy has not been widely taught in Bangladesh. Against this background, at the age of information superabundance, citizens should learn to judge the reliability of news reports and other sources of information that is passed along their communication network and news media outlets. The concept of news literacy has emerged from this realization. However, as an academic terminology, the concept of news literacy is rather new in Bangladesh. -

Narayanganj Located in Central Bangladesh, Narayanganj Is Part of Dhaka, with an Area of 760 Square Kilometres

Narayanganj Located in central Bangladesh, Narayanganj is part of Dhaka, with an area of 760 square kilometres. About 34 kilometres away from the nation’s capital, Narayanganj is located on the banks of the Shitalakshya river. It is one of the major hubs of business and industry in Bangladesh, especially for jute trade, processing plants and the textiles sector. Photo credit: BRAC BRAC operates a majority of its programmes in Narayanganj Happy students of BRAC primary school including microfinance, education (BEP), health, nutrition and population (HNPP), water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), human rights and legal aid services WASH (HRLS), community empowerment At a glance Sanitation coverage 91% (CEP), and gender justice and Deep tubewells installed 171 As of December, 2014 diversity (GJD). Among them Sanitary latrines microfinance largest programme in installed in school 30 the area, covering approximately Microfinance Loans for sanitary latrines 1,896 100,000 clients. Additionally, WASH Village organisation (VOs) 1,670 has achieved 91 per cent sanitation Member 123,463 HRLS coverage in Narayanganj. Borrowers 75,852 Human rights and legal education Progoti (HRLE) shebikas 138 Small enterprise clients 15,050 HRLE graduates 33,671 General information Legal aid clinics 5 BEP Population 2,095,000 Primary schools 460 CEP Pre-primary schools 130 Unions 41 Groups/members 60/3,600 Adolescent development Villages 1,374 Community educators 3,260 programme (ADP) centres 37 Children (0-15) 67,000 Schools/students 40/12,000 Community libraries 31 Primary schools 1,425 Student watch groups/members 40/1,000 Literacy rate 52% HNPP Community watch Hospitals 6 group/members 40/600 NGOs 35 Health workers 117 Health volunteers 1,034 Banks 40 Social enterprises Bazaars 199 Aarong Outlets 1 Although every effort has been made to include and verify the accuracy of relevant information in this fact sheet, users are urged to check independently on matters of specific interest. -

Agricultural Land Cover Change in Gazipur, Bangladesh, in Relation to Local Economy Studied Using Landsat Images

Advances in Remote Sensing, 2015, 4, 214-223 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ars http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ars.2015.43017 Agricultural Land Cover Change in Gazipur, Bangladesh, in Relation to Local Economy Studied Using Landsat Images Tarulata Shapla1,2, Jonggeol Park3, Chiharu Hongo1, Hiroaki Kuze1 1Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan 2Department of Agroforestry and Environmental Science, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh 3Graduate School of Informatics, Tokyo University of Information Sciences, Chiba, Japan Email: [email protected] Received 17 June 2015; accepted 21 August 2015; published 24 August 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Land classification is conducted in Gazipur district, located in the northern neighborhood of Dha- ka, the capital of Bangladesh. Images of bands 1 - 5 and 7 of Landsat 4 - 5 TM and Landsat 7 ETM+ imagery recorded in years 2001, 2005 and 2009 are classified using unsupervised classification with the technique of image segmentation. It is found that during the eight year period, paddy area increased from 30% to 37%, followed by the increase in the homestead (55% to 57%) and urban area (1% to 3%). These changes occurred at the expense of the decrease in forest land cover (14% to 3%). In the category of homestead, the presence of different kinds of vegetation often makes it difficult to separate the category from paddy field, though paddy exhibits accuracy of 93.70% - 99.95%, which is better than the values for other categories. -

Farmers' Organizations in Bangladesh: a Mapping and Capacity

Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: Investment Centre Division A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla – 00153 Rome, Italy. Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component FAO Representation in Bangladesh House # 37, Road # 8, Dhanmondi Residential Area Dhaka- 1205. iappta.fao.org I3593E/1/01.14 Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component Food and agriculture organization oF the united nations rome 2014 Photo credits: cover: © CIMMYt / s. Mojumder. inside: pg. 1: © FAO/Munir uz zaman; pg. 4: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 6: © FAO / F. Williamson-noble; pg. 8: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 18: © FAO / i. alam; pg. 38: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 41: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 44: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 47: © J.F. lagman; pg. 50: © WorldFish; pg. 52: © FAO / i. nabi Khan. Map credit: the map on pg. xiii has been reproduced with courtesy of the university of texas libraries, the university of texas at austin. the designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and agriculture organization of the united nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. the mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

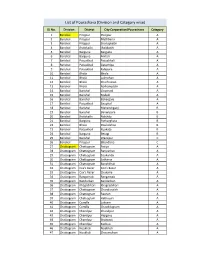

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

Bangladesh Cyclone Sidr Was the Second Occasion Habitat for Humanity* Responded to a Natural Disaster in Ban- Gladesh

Habitat for Humanity: The Work Transitional Shelters As480 of December 2008 Latrines As480 of February 2009 A Day in November On 15th November 2007, Cyclone Sidr bore down on southern Bangladesh, unleashing winds that peaked at 250 km. per hour and six-meter high tidal surges that washed away entire villages. Cyclone Sidr killed over 3,000 people, a fraction of the more destructive cyclones that struck in 1970 and 1991 which claimed more than 600,000 lives. But that was still too many. According to reports from the worst hit areas, many of the dead and injured were crushed when trees fell onto poorly constructed houses made of thatch, bam- boo or tin. Others drowned when they, together with their houses, were swept away by the torrents of water. TANGAIL Tangail 15 Nov 18.00 UCT Wind Speed 190 kmph INDIA DHAKA SHARIATPUR BANGLADESH MADARIPUR Madaripur GOPALGANJ Madaripur Gopalganj BARISAL INDIA SATKHIRA Bagrthat JHALAKTHI BAGTHAT Pirojpur PATUAKHALI PIROJPUR KHULNA BHOLA Mirzagani Patuakhali Barguna BARGUNA Bay of Bengal Badly Affected Severely Affected Most Severely Affected Storm Track Worst Affected BURMA 0 50 100 Km TANGAIL Tangail 15 Nov 18.00 UCT Wind Speed 190 kmph INDIA Extent of DHAKA the Damage SHARIATPUR BANGLADESH MADARIPUR More than eight million people in 31 districts were Madaripur reportedly affected by Cyclone Sidr. More than 9,000 GOPALGANJ Madaripur schools were flattened or swept away, with extensive Gopalganj damage reported to roads, bridges and embankments. BARISAL Some two million acres of crops were damaged and INDIA SATKHIRA Bagrthat JHALAKTHI over 1.25 million livestock killed. -

SASEC Dhaka-Northwest Corridor Road Project Phase 2 Was Approved in October 2017

Semiannual Social Monitoring Report Loan No- 3592 Project No. 40540-017 December 2018 South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Dhaka-Northwest Corridor Road Project, Phase 2 - Tranche 1 This Semiannual Social Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Social Monitoring Report Third Semi-Annual Report BAN: SASEC Dhaka Northwest Corridor Road Project, Phase- 2 Improvement of Elenga-Hatikamrul-Rangpur Road to a 4 Lane Highway February 2019 Prepared by Ms. Hasina Khatun, Social Development Specialist, Project Implementation Consultant (PIC), SASEC RCP-II on behalf of the Roads and Highways Department (RHD), Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges for the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 04 February’ 2019) Currency Unit – Bangladesh Taka (BDT) BDT 1.00 = $0.0119164 $1.00 BDT 83.9179 1 BDT = 0.0119164 USD1 USD = 83.9179 BDT. WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1ha (Hectare) = 10000sq.m (square meter) Or 2.47 Acre Or 247 Decimal 1 Acre = 100 Decimal 1 km (kilometer) = 1000 m (Meter) 1 Metric Ton = 1000 kg (kilogram) ABBREVIATIONS AB - -

District Statistics 2011 Bhola

জলা পিরসংান 3122 ভালা District Statistics 2011 Bhola December 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 District Statistics 2011 Published in December, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP), FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contact: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii District Statistics 2011 Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021. -

1 Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Rural

1 Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Economics, XL 1&2 (2019): 1-16 SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF POVERTY IN RURAL BANGLADESH Md. Farouq Imam1 Mohammad Amirul Islam1 Md. Akhtarul Alam1* Md. Jamal Hossain1 Sumonkanti Das2 ABSTRACT Poverty is a complex phenomenon and most of the developing countries are struggling to overcome the problem. Small area estimation offers help to allocate resources efficiently to address poverty at lower administrative level. This study used data from Census 2011 and Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES)-2010. Using ELL and M-Quantile methods, this study identified Rangpur division as the poorest one where Kurigram is the poorest district. Finally, considering both upper and lower poverty lines this study identified the poverty estimates at upazila level of Rangpur division using ELL and M-Quantile methods. The analyses found that 32% of the households were absolute poor and 19% were extremely poor in rural Bangladesh. Among the upazilas under Rangpur division Rajarhat, Ulipur, Char Rajibpur, Phulbari, Chilmari, Kurigram Sadar, Nageshwari, and Fulchhari Upazilas have been identified as the poorest upazilas. Keywords: Small area, poverty, ELL, M-Quantile methods I. INTRODUCTION Bangladesh is a developing country in the south Asia. According to the recent statistics by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS, 2017, HIES, 2010) the per capita annual income of Bangladesh is US$1610, estimated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is 7.28, and the percentage below the poverty line (upper) is 24.30 percent. The population is predominantly rural, with about 70 percent people living in rural areas (HIES, 2016). In Bangladesh, poverty scenario was first surveyed in 1973-1974.