Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

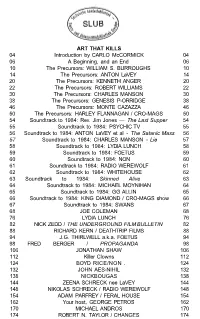

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

September 11 Attacks

Chapter 1 September 11 Attacks We’re a nation that is adjusting to a new type of war. This isn’t a conventional war that we’re waging. Ours is a campaign that will have to reflect the new enemy…. The new war is not only against the evildoers themselves; the new war is against those who harbor them and finance them and feed them…. We will need patience and determination in order to succeed. — President George W. Bush (September 11, 2001) Our company around the world will continue to operate in this sometimes violent world in which we live, offering products that reach to the higher and more positive side of the human equation. — Disney CEO Michael Eisner (September 11, 2001) He risked his life to stop a tyrant, then gave his life trying to help build a better Libya. The world needs more Chris Stevenses. — U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (September 12, 2012) We cannot have a society in which some dictators someplace can start imposing censorship here in the United States because if somebody is able to intimidate us out of releasing a satirical movie, imagine what they start doing once they see a documentary that they don’t like or news reports that they don’t like. That’s not who we are. That’s not what America is about. — President Barack Obama (December 19, 2014) 1.1 September 11, 2001 I was waking up in the sunny California morning on September 11, 2001. Instead of music playing on my radio alarm clock, I was hearing fragments of news broadcast about airplanes crashing into the Pentagon and the twin towers of the World Trade Center. -

(Genesis P-Orridge) 1950 Born in Manchester, UK Lives and Works In

BREYER P-ORRIDGE (Genesis P-Orridge) 1950 Born in Manchester, UK Lives and works in New York Selected Solo Exhibitions 2016 Blue Blood Virus, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York Try To Altar Everything, The Rubin Museum, New York 2015 “Breakng Sex,” Galerie Bernhard, Zurich, Switzerland 2014 “Life as a Cheap Suitcase,” Summerhall, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 S/he is Her/e, Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh PA 2012 La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse, Montreal, Canada NADA Art Fair Miami, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS booth #305, Miami, FL I’m Mortality, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York THEE…NESS: An Evening with Genesis BREYER P-ORRIDGE, Salvor Projects, New York 2011 Blood – Sex – Magick, Christine Konig Galerie, Vienna, Austria 2010 Spillage… Rupert Goldsworthy Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2009 30 Years of Being Cut Up, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York 2008 Collaborative Works, Mason Gross Galleries, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ 2006 We Are But One…, Participant Inc., New York 2004 Painful But Fabulous, Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, Germany Regeneration Hex, Ecart Gallery, Art Fair, Basel, Switzerland 2003 Painful But Fabulous, A22 Gallery, London UK BREYER P-ORRIDGE Sigils, VAV Gallery, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada 2002 Genesis P-Orridge, Galerie Station/Mousonturm, Frankfurt, Germany 2001 Expanded Photographs 1970-2001, ECART Gallery, Art 32 Basel, Sweizer Mustermesse, Basel, Switzerland Candy Factory (with Eric Heist), Centre Of Attention, London, England Candy Factory (with Eric Heist), TEAM Gallery, Chelsea, New York 1995 Genesis P-Orridge-Works, SERFOZO Artadventures, Zurich, Switzerland 1994 Esoterrorist - Retrospective, Rita Dean Gallery, San Diego, CA 1976 Marianne Deson Gallery, Chicago, IL N.A.M.E. Gallery, Chicago, IL Kit Schwartz Studio, Chicago, IL Idea Gallery, Santa Monica, CA Los Angelis Institute Of Contemporary Arts, Los Angeles, CA Prostitution, Institute Of Contempoary Arts, London, England. -

\-WG.~\· B. Uru).Y Professor Philip Armstrong Adviser Comparative Studies Graduate,, Program ABSTRACT

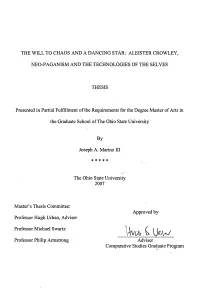

THE WILL TO CHAOS AND A DANCING STAR: ALEISTER CROWLEY, NEO-P AGANISM AND THE TECHNOLOGIES OF THE SELVES THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joseph A. Marino III * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Master's Thesis Committee: Approved by Professor Hugh Urban, Adviser Professor Michael Swartz \-WG.~\· b. Uru).y Professor Philip Armstrong Adviser Comparative Studies Graduate,, Program ABSTRACT Entrenched in Victorian England and raised in a puritanical Christian family, Aleister Crowley delved into Western Esotericism and the study of ritual magic as a means to subvert the stifling environment into which he was bom. Among his chief acts of subversion were his many displays of a very fluid and malleable identity. He played with “selves” like they were merely wardrobes for a day and found himself developing more fully for the breadth of experience that he achieved from such practices. In the wake of Friedrich Nietszche, Crowley looked to the strength of each individual will to deny being identified by traditional systems such as Christianity or “Modernity,” pushing instead for a chaotic presentation of the self that is both wholly opposed to external authority and wholly enthusiastic about play, contradiction and experimentation. Through the lens of Michel Foucault’s “Technologies of the Self' and Judith Butler’s notion of performativity, one can come to see Crowley’s performances (through dress, pseudonyms, literary license and more) as operations that he performs on himself to knowingly affect a change in his identity. -

Jennifer Granick in the News

JENNIFER GRANICK IN THE NEWS source: Stanford Law School Library/Digital Reserves Granick CNET News.com Feb. 1, 2001, Thur. Cyberlawyer: Don't Blame The Hackers, by Robert Lemos Granick The Atlanta Journal And Const. p.4E Feb. 7, 2001, Wed. Parody Webmaster Defends CNNf Spoof, by Jeffry Scott Granick Information Security p.66 Mar-01 We're The Freedom People, Interview by Richard Thieme Granick Wired News 2:00 AM PST Mar. 9, 2001, Fri. Lawyers With Hacking Skills, by Aparna Kumar Granick The San Francisco Chronicle p.B1 Mar. 15, 2001, Thur. Intimate Details: Credit Cards, Social Security Numbers And… Granick ZDNet News May 1, 2001, Tue. Lawyers Slam FBI 'Hack', by Robert Lemos Granick The Lawyers Weekly May 18, 2001, Fri. Is 'Hacktivism' A Crime?, by Lesia Stangret Granick Stanford Lawyer p.8 Summer 2001 Cyber Expert Lessig Founds Center For Internet And Society Granick InfoWorld Daily News Jul. 16, 2001, Mon. Def Con, Black Hat: Hacker Shows Offer Tips, Tricks Granick ZDNet News from ZDWire Jul. 17. 2001, Tue. FBI Nabs Russion Expert At Def Con, by Robert Lemos Granick ZDNet News from ZDWire Jul. 18, 2001, Wed. Arrest Fuels Adobe Copyright Fight, by Robert Lemos Granick TheStandard.com (The Industry St.) Jul. 18, 2001, Wed. Russsian Arrested For Alleged DMCA Violations, IDG Granick InfoWorld Daily News Jul. 18, 2001, Wed. Def Con: Russian Arrested For Alleged Copyright Violations Granick EFF (http://www.eff.org/) Jul. 22, 2001, Sun. For Immediate Release: July 17, 2001: S.F., The FBI arrested… Granick The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Jul. -

(Genesis P-Orridge) 1950 Born in Manchester, UK Lives and Works In

BREYER P-ORRIDGE (Genesis P-Orridge) 1950 Born in Manchester, UK Lives and works in New York Selected Solo Exhibitions 2017 Room 40, Brisbane, Australia Tree of Life, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York 2016 Thee Ghost, Lockup International, Mexico City, Mexico Blue Blood Virus, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York Try To Altar Everything, The Rubin Museum, New York 2015 Breaking Sex, Galerie Bernhard, Zurich, Switzerland 2014 Life as a Cheap Suitcase, Summerhall, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 S/he is Her/e, Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh PA 2012 La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse, Montreal, Canada NADA Art Fair Miami, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS booth #305, Miami, FL I’m Mortality, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York THEE…NESS: An Evening with Genesis BREYER P-ORRIDGE, Salvor Projects, New York 2011 Blood – Sex – Magick, Christine Konig Galerie, Vienna, Austria 2010 Spillage… Rupert Goldsworthy Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2009 30 Years of Being Cut Up, INVISIBLE-EXPORTS, New York 2008 Collaborative Works, Mason Gross Galleries, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ 2006 We Are But One…, Participant Inc., New York 2004 Painful But Fabulous, Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, Germany Regeneration Hex, Ecart Gallery, Art Fair, Basel, Switzerland 2003 Painful But Fabulous, A22 Gallery, London UK BREYER P-ORRIDGE Sigils, VAV Gallery, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada 2002 Genesis P-Orridge, Galerie Station/Mousonturm, Frankfurt, Germany 2001 Expanded Photographs 1970-2001, ECART Gallery, Art 32 Basel, Sweizer Mustermesse, Basel, Switzerland Candy Factory (with Eric Heist), Centre Of Attention, London, England Candy Factory (with Eric Heist), TEAM Gallery, Chelsea, New York 1995 Genesis P-Orridge-Works, SERFOZO Artadventures, Zurich, Switzerland 1994 Esoterrorist - Retrospective, Rita Dean Gallery, San Diego, CA 1976 Marianne Deson Gallery, Chicago, IL N.A.M.E. -

Advanced Teaching Online 4Th Edition

ADVANCED TEACHING ONLINE Advanced About the Author Teaching William A. Draves is an internationally Fourth Edition recognized teacher, author and consultant, Online and one of the foremost authorities on online learning. More than 6,000 faculty have taken his online courses. He is President of the Learning Resources Network (LERN), the world’s leading association in lifelong and online learning with more than 5,000 members. Draves is the most-quoted expert on lifelong learning by the nation’s media, William A. Draves having been interviewed by The New York Times, BBC, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio, NBC Nightly News, and Wired.com, among others. William A. Draves He holds a master’s degree in adult education from The George Washington University in Washington, DC. With co-author Julie Coates he has also written Education in the 21st Century, and their classic work Nine Shift: Work, Life and Education in the 21st Century. He is also author of How to Teach Adults and Energizing the Learning Environment. A popular speaker, he has keynoted conferences in Russia, Japan, Australia, England, Slovenia, and throughout Canada and the United States. Draves does on-campus faculty development seminars and has a two-day seminar for college presidents and other senior decision makers in higher education. ISBN 978-1-57722-027-5 90000 > LERN 9 781577 220275 William A. Draves “Draves knows how the Internet is changing the education experience.” Judy Bryan, Culture Editor, Wired News, Wired.com “A must read for administrators, teachers and anyone interested in the power and the future of online learning and teaching.” Jan Wahl, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA “Draves has approached this timely topic in a functional, no-nonsense way. -

Access to the Airwaves, My Fight for Free Radio

www.loompanics.com Access to the Airwaves, My Fight for Free Radio; Allan H. Weiner as told to Anita Louise McCormick; 1997 Against Empire; Michael Parenti; 1995 Against Method; Paul Feyerabend; 1993 Al Quaida and What It Means to Be Modern; John Gray; 2003 Armed Defense, Gunfight Survival For the Householder and Businessman; Burt Rapp; 1989 The Art of Contrary Thinking; Humphrey B. Neill; 2004 Ask Me No Questions, I`ll Tell You No Lies: How to Survive Being Interviewed, Interrogated, Questioned, Quizzed, Sweated, Grilled…; Jack Luger; 1991 The B&E Book, Burglary Techniques and Investigation, A Complete Manual; Burt Rapp; 1989 Backyard Meat Production, How To Grow All The Meat You Need In Your Own Backyard; Anita Evangelista; 1997 Bad Girls Do It! An Encyclopedia of Female Murderers; Michael Newton; 1993 Be Your Own Dick, Private Investigating Made Easy, John Q. Newman; 1999 Beating the Check, How to Eat Out Without Paying; Mick Shaw; 2000 The Big Book of Secret Hiding Places; Jack Luger; 1999 Birth Certificate Fraud; Richard P. Kusserow; 1988 Black Collar Crimes, An Encyclopedia of False Prophets and Unholy Orders; Michael Newton; 1998 The Breakdown of Nations; Leopold Kohr; 2001 Build A Catapult In Your Backyard; Bill Wilson; 2001 Code Making And Code Breaking; Jack Luger; 1990 Combat Knife Throwing, A New Approach to Knife Throwing and Knife Fighting; Ralph Thorn; 2002 Community Technology; Karl Hess; 1979 The Complete Guide to Lock Picking; Eddie the Wire; 1981 Cops! Madia vs Reality; Tony Lesce; 2000 Counterfeit I.D. Made Easy; Jack Luger; 1990 Country Living is Risky Business; Nick & Anita Evangelista; 2000 Credit Power! Rebuild Your Credit in 90 Days or Less! John Q. -

You Are Being Lied To

1 This anthology © 2001 The Disinformation Company Ltd. All of the articles in this book are © 1992-2000 by their respective authors and/or original publishers, except as specified herein, and we note and thank them for their kind permission. Published by The Disinformation Company Ltd., a member of the Razorfish Subnetwork 419 Lafayette Street, 4th Floor New York, NY10003 Tel: 212.473.1125 Fax: 212.634.4316 www.disinfo.com Editor: Russ Kick Design and Production: Tomo Makiura and Paul Pollard First Printing March 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a database or other retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means now existing or later discovered, including without limitation mechanical, electronic, photographic or other- wise, without the express prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Card Number: 00-109281 ISBN 0-9664100-7-6 Printed in Hong Kong by Oceanic Graphic Printing Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution 1045 Westgate Drive, Suite 90 St. Paul, MN 55114 Toll Free: 800.283.3572 Tel: 651.221.9035 Fax: 651.221.0124 www.cbsd.com Disinformation is a registered trademark of The Disinformation Company Ltd. The opinions and statements made in this book are those of the authors concerned. The Disinformation Company Ltd. has not verified and neither confirms nor denies any of the foregoing. The reader is encouraged to keep an open mind and to independently judge for him- or herself whether or not he or she is being lied to. The Disinform a tion Guide to Media Distorti o n , Hi s t o r i c a l Whi t e washes and Cultural Myths Edited by Russ Kick ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anne Marie, who restored my faith in the truth. -

Techno- Philosopher

glory, dazzling and beftiddling both characters and audience. Thien a little like that data — at once dazzling and befuddling — he enjo^ the efiect. Thiemeworks, the company he runs from his house, is hi he reaches the global community in cyberspace. His mind works in Techno- bursts of information and he leaps from esoteric topic to esoteric t After swerving through conversations on quantum hacking. String Theory as metaphor, and what is plagiarism on the computer, it tal a team of horses to slow him down and demand: "Just what is it yo philosopher do or are in five sentences or less?" To which Thieme replies: "I'm techno-philosopher." That certainly clears things up, doesn't it? story by Judy Steininger • Photography by John Roberts With a bachelor of arts degree from Northwestern University anc master's degree from the University of Chicago he taught literature the 1970s, served as a priest during the '80s until he had a falling o with a bishop on the East Coast, and began to see the transformati^ power of the computer in the '90s. He learned from "15-year-old mentors because this stuff hasn't been around long enough to have an academic discipline. It is being made up as we go along. "What I do for companies and governmental agencies is interpre changes caused by technology. I interpret for people who see a pie but not the big picture. I edit life for people who don't have the tin When urged to be a little more specific, Thieme explains, "I deal w the human implications of technology." OK, we can grapple with tl By prowling the Internet and attending conferences, Thieme beg; understand the borderless territory of cyberspace. -

![Ron Gula: [00:00:04] Hi There](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0575/ron-gula-00-00-04-hi-there-10210575.webp)

Ron Gula: [00:00:04] Hi There

Ron Gula: [00:00:04] Hi there. This is Ron and Cyndi Gula with another episode of the Gula tech cyber fiction show. Cindy, how are you? Cyndi Gula: [00:00:10] I'm doing great, Ron. How are you doing? Ron Gula: [00:00:11] Doing very well because today our guest is Richard Thieme. Cindy and I have known Richard for a long time. I think long time becomes more of an insult or something like that after a while. But ages, right? Richard how are you doing? Richard Thieme: [00:00:24] I'm doing great. And yeah, it's been decades. not years. Ron Gula: [00:00:27] That's right. That's right. So today we are gonna talk about Richard Thieme's background, which is as a 25 time Def Con speaker, author of multiple books, including works of fiction and works of science fiction and works of nonfiction [ Richard Thieme: [00:00:42] laughs] Ron Gula: [00:00:42] Which is good stuff. Let's start off with Def Con and Black Hat. Richard, this is the first year you're not there in person. How has Def Con changed? over the years? Richard Thieme: [00:00:50] Just about the first. I didn't go last time, but I did go to HOPE, which was a reasonable facsimile thereof. Yeah, it's been 25 years of Def Con. How has it changed? I prerecorded the talk this year and sent it to them because I just couldn't risk Vegas for four days for a variety of reasons. -

You Are Being Lied To

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anne Marie, who restored my faith in the truth. Thanks of a personal nature are due to Anne, Ruthanne, Jennifer, and (as always) my parents, who give me support in many ways. –Russ Kick The same goes for that unholy trinity of Billy, Darrell, and Terry, who let me vent and make me laugh. I’d like to thank Richard Metzger and Gary Baddeley for letting me edit the book line and taking a laissez-faire approach. Also, many thanks go to Paul Pollard and Tomo Makiura, who turned a bunch of computer files into the beautiful object you now hold in your hands. And thanks also head out to the many other people involved in the creation and distribution of this book, including everyone at Disinformation, RSUB, Consortium, Green Galactic, the printers, the retailers, and elsewhere. It takes a lot of people to make a book! Last but definitely not least, I express my gratitude toward all the con- tributors, without whom there would be no You Are Being Lied To. None of you will be able to retire early because of appearing in these pages, so I know you contributed because you believe so strongly in what you’re doing. And you believed in me, which I deeply appreciate. –Russ Kick Major thanks are due to everyone at The Disinformation Company and RSUB, Julie Schaper and all at Consortium, Brian Pang, Adam Parfrey, Brian Butler, Peter Giblin, AJ Peralta, Steven Daly, Stevan Keane, Zizi Durrance, Darren Bender, Douglas Rushkoff, Grant Morrison, Joe Coleman, Genesis P-Orridge, Sean Fernald, Adam Peters, Alex Burns, Robert Sterling, Preston Peet, Nick Mamatas, Alexandra Bruce, Matt Webster, Doug McDaniel, Jose Caballer, Leen Al-Bassam, Susan Mainzer, Wendy Tremayne and the Green Galactic crew, Naomi Nelson, Sumayah Jamal–and all those who have helped us along the way, including you for buying this book! –Gary Baddeley and Richard Metzger Acknowledgements 4.