Identity, Reality, and Truth in Memoirs from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars Travis L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

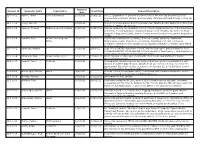

Requests Report

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Congressional Record—Senate S4920

S4920 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE April 8, 2003 HONORING OUR ARMED FORCES in our hearts. She will not be forgot- as ‘‘a mild-mannered, quiet child’’ who Mrs. HUTCHISON. Mr. President, ten. It gives us comfort to know that attended Bible study every Wednesday today I am going to continue what the she is at peace right now.’’ night before joining the Army. Senate has been doing since our troops Behind me are the pictures of some The 507th Maintenance Company still started the invasion of Iraq, and that is who have died in action, and I am has five soldiers who are prisoners of to take the first period before we go on going to speak about each of them. war. They are SP Shoshana Johnson, In Texas, there is a town called Com- to the business of the day to salute the SP Edgar Hernandez, SP Joseph Hud- fort that lived up to its name by em- son, PFC Patrick Miller, and SGT troops who are in the field protecting bracing and comforting the parents of James Riley. I have talked with Claude our freedom. Today, I want to salute the members SP James Kiehl. In Comfort, TX, the Johnson, Shoshana’s father, several times. He and his wife Eunice are car- of the 507th Maintenance Company. parents of SP James M. Kiehl are being ing for Shoshana’s 2-year-old daughter. This is the company out of Fort Bliss comforted by their friends and neigh- bors. The 6-foot 8-inch soldier was a These five have not been seen pub- in El Paso, TX, who really were the licly since several hours after they first to be captured, the first prisoners high school basketball player and a member of the band. -

Department of Veterans Affairs

1 DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS 2 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON FORMER PRISONERS OF WAR 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Department of Veterans Affairs 10 Advisory Committee on Former Prisoners of War 11 Biannual Meeting, Monday, November 17, 2014 12 SpringHill Suites by Marriott 13 1800 Yale Avenue, Seattle, Washington 14 15 16 17 18 19 Reported by: Catherine E. Black, Certified Court Reporter CCR No. 2266 20 State of Washington 21 Roger G. Flygare & Associates, Inc. Professional Court Reporters, 22 Videographers & Legal Transcriptionists 1715 South 324th Place, Suite 250 23 Federal Way, Washington 98003 (800) 574-0414 - main 24 www.flygare.com - scheduling [email protected] - email 25 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON FORMER PRISONERS OF WAR -- NOVEMBER 17, 2014 1 FORMER PRISONERS OF WAR ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: 2 Thomas M. McNish, MD, MHP, FPOW Committee Chairman 3 San Antonio, Texas FPOW Vietnam 4 5 Michael R. Ambrose, MD, MPH, FAAFP Former Director, Robert E. Mitchell Center 6 Mobile, Alabama 7 Hal Kushner, MD, FACS, COL (ret) US Army 8 Daytona Beach, Florida FPOW Vietnam 9 10 Tom Hanton, President, NAM POWS Mount Pleasant, South Carolina 11 FPOW Vietnam 12 Shoshana Johnson 13 State of Texas FPOW Operation Iraqi Freedom 14 15 Norman Bussel, National Service Officers Montrose, Virginia 16 FPOW World War II 17 The Rev. Dr. Robert G. Certain 18 Chaplain, Colonel, USAFR (Retired) FPOW Vietnam 19 20 Robert W. Fletcher Department of Veteran Affairs 21 Advisory Committee on Former POWs Ann Arbor, Michigan 22 FPOW Korea 23 Eric R. Robinson, Analyst, Interagency Data Sharing 24 Designated Federal Officer Washington, D.C. -

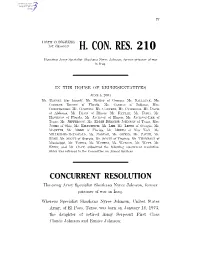

H. Con. Res. 210

IV 108TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 210 Honoring Army Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, former prisoner of war in Iraq. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JUNE 5, 2003 Mr. RANGEL (for himself, Mr. BISHOP of Georgia, Mr. BALLANCE, Ms. CORRINE BROWN of Florida, Ms. CARSON of Indiana, Mrs. CHRISTENSEN, Mr. CLYBURN, Mr. CONYERS, Mr. CUMMINGS, Mr. DAVIS of Alabama, Mr. DAVIS of Illinois, Mr. FATTAH, Mr. FORD, Mr. HASTINGS of Florida, Mr. JACKSON of Illinois, Ms. JACKSON-LEE of Texas, Mr. JEFFERSON, Ms. EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON of Texas, Mrs. JONES of Ohio, Ms. KILPATRICK, Ms. LEE, Mr. LEWIS of Georgia, Ms. MAJETTE, Mr. MEEK of Florida, Mr. MEEKS of New York, Ms. MILLENDER-MCDONALD, Ms. NORTON, Mr. OWENS, Mr. PAYNE, Mr. RUSH, Mr. SCOTT of Georgia, Mr. SCOTT of Virginia, Mr. THOMPSON of Mississippi, Mr. TOWNS, Ms. WATERS, Ms. WATSON, Mr. WATT, Mr. WYNN, and Mr. CLAY) submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Armed Services CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Honoring Army Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, former prisoner of war in Iraq. Whereas Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, United States Army, of El Paso, Texas, was born on January 18, 1973, the daughter of retired Army Sergeant First Class Claude Johnson and Eunice Johnson; 2 Whereas upon receiving orders on February 2003, Specialist Johnson was deployed to the Persian Gulf region as part of the Army’s 507th Maintenance Company; Whereas on March 23, 2003, Specialist Johnson’s unit was ambushed by Iraqi troops in Nasiriyah, Iraq, and Spe- cialist Johnson -

Home Sweet Home

I Home Sweet Home Family, friends await the homecoming of loved ones in Iraq Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Corpsman Mark Delay, is headed based at Fort Bliss, Texas, remain cooked for him. He’s told me tit By Chelsea J. Carter Division to Twentynine Palms, home aboard the Lincoln, but her overseas, although five former he wants green chile chide THE ASSOCIATED PRESS Calif. thoughts also are with those POWs from the company returned enchiladas,” said Natalie Hutto She just hopes he’s back by whose spouses remain in the to the base Saturday. Two Apache of El Paso, Texas. SAN DIEGO — Audrey August, in time for the birth of Middle East. helicopter crewmen who were Everett plans a welcome Trevino has played it over in her their second child. “Our husbands are on the way among the rescued POWs also party for the USS Lincoln, v mind a thousand times: Her Navy “The rumors are starting, and home. There are men on the front returned Saturday to their base. cheering crowd waving 2i husband steps off the ship after you just hope they are true,” she lines who are going to be there Fort Hood, Texas. yellow pompoms. Club Broadra months at sea supporting the war said. for months,” she said. “So it’s “We will have several welcome Ten-year-old Jake Rabidou of hard to be so excited.” has even begun collecting in Iraq, grabs her in his arms and celebrations, not only for (the tions from local customers so kisses her. Camp Lejeune, N.C., also does Some cities already have had n’t know how long he’s going to homecoming celebrations. -

WWII Question of “Why We !Ght” with “For the Soldiers Themselves.” Forrest Gump W!/ W" “S)00$%# #!" T%$$0.”: R!"#$%&'-+ E1$+)#&$2

W!" W# “S$%%&'( (!# T'&&%)”: R!#(&'*+,- E.&-$(*&/) R!"#$ S%&'( ) is essay tracks the genealogy of the contemporary call to “support the troops,” a rhetoric that includes but goes beyond the strategic and argumentative use of the phrase itself. Support-the-troops rhetoric has two major functions: de*ection and dissociation. De*ection involves discursive trends in play since Vietnam that have rede+ned war as a +ght to save our own soldiers—especially the captive soldier—rather than as a struggle for policy goals external to the military. As such, this discourse directs civic attention away from the question of whether the particular war policy is just. ) e essay explicates these trends through an examination of the POW/MIA, war +lm, and the symbol of the yellow ribbon. ) e second trope, dissociation, quarantines the citizen from questions of military action by manufacturing distance between citizen and soldier. Dissociation o, en goes further to de+ne civic deliberation and dissent as an attack on the soldier body and thus an ultimate immoral act. ) is essay explores this trope through executive rhetoric, an analysis of the particular phrase “support the troops,” metaphor for war, and John Kerry’s run for the presidency in -../. Both de*ection and dissociation work to discipline and mute public deliberation in matters of war. ) e essay concludes by considering strategies for reopening spaces for democratic deliberation. R!"#$ S%&'( is Assistant Professor of Speech Communication at the University of Georgia in Athens. © 2009 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. All rights reserved. Rhetoric & Public Affairs Vol. 12, No. 4, 2009, pp. -

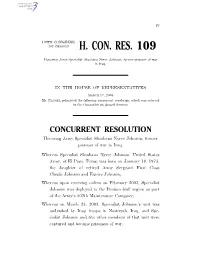

H. Con. Res. 109

IV 109TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. CON. RES. 109 Honoring Army Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, former prisoner of war in Iraq. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES MARCH 17, 2005 Mr. RANGEL submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Armed Services CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Honoring Army Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, former prisoner of war in Iraq. Whereas Specialist Shoshana Nyree Johnson, United States Army, of El Paso, Texas, was born on January 18, 1973, the daughter of retired Army Sergeant First Class Claude Johnson and Eunice Johnson; Whereas upon receiving orders on February 2003, Specialist Johnson was deployed to the Persian Gulf region as part of the Army’s 507th Maintenance Company; Whereas on March 23, 2003, Specialist Johnson’s unit was ambushed by Iraqi troops in Nasiriyah, Iraq, and Spe- cialist Johnson and five other members of that unit were captured and became prisoners of war; 2 Whereas Specialist Johnson suffered gunshot wounds in both ankles and rough treatment by her captors; Whereas Specialist Johnson’s interrogation by her captors was seen by television viewers around the world in a vid- eotape released by her Iraqi captors; Whereas Specialist Johnson’s plight resonated in the hearts of all Americans; Whereas Specialist Johnson, as well as four others from her unit and two helicopter pilots, were rescued by United States Marines on April 13, 2003; Whereas upon that rescue, all eight United States military personnel who were captured and held as prisoners of war during Operation -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:10-cv-02119-RMC Document 44 Filed 11/02/12 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) ANTHONY SHAFFER, ) ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 10-2119 (RMC) ) DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff Anthony Shaffer is an intelligence officer who was employed with the Defense Intelligence Agency, an operational component of the Department of Defense, from 1995-2006. After this, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve and retired as Lieutenant Colonel in 2011. Mr. Shaffer served two tours of duty in Afghanistan. Together with a ghost writer, Mr. Shaffer authored a book entitled Operation Dark Heart: Spycraft and Special Ops on the Frontlines of Afghanistan and the Path to Victory, which he describes as an eyewitness account of the 2003 “tipping point” of the war in Afghanistan. He is required by several secrecy agreements to submit all of his writings for prepublication review to ensure they do not contain classified information. Mr. Shaffer complains that several executive agencies improperly designated certain information in his book as classified and imposed a restraint on his First Amendment right to publish his book. The agencies assert that Mr. Shaffer lacks standing to bring his claim because he sold control of his book to his publisher in the United States; they move to dismiss the Amended Complaint. The motion will be denied. Mr. Shaffer has standing Case 1:10-cv-02119-RMC Document 44 Filed 11/02/12 Page 2 of 8 because he maintains rights to publish an unredacted version of his book and, if the redactions are overbroad, to otherwise “publish” the non-classified information in his book. -

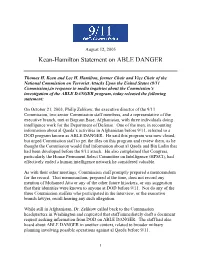

Kean-Hamilton Statement on ABLE DANGER

August 12, 2005 Kean-Hamilton Statement on ABLE DANGER Thomas H. Kean and Lee H. Hamilton, former Chair and Vice Chair of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (9/11 Commission),in response to media inquiries about the Commission’s investigation of the ABLE DANGER program, today released the following statement: On October 21, 2003, Philip Zelikow, the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, two senior Commission staff members, and a representative of the executive branch, met at Bagram Base, Afghanistan, with three individuals doing intelligence work for the Department of Defense. One of the men, in recounting information about al Qaeda’s activities in Afghanistan before 9/11, referred to a DOD program known as ABLE DANGER. He said this program was now closed, but urged Commission staff to get the files on this program and review them, as he thought the Commission would find information about al Qaeda and Bin Ladin that had been developed before the 9/11 attack. He also complained that Congress, particularly the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI), had effectively ended a human intelligence network he considered valuable. As with their other meetings, Commission staff promptly prepared a memorandum for the record. That memorandum, prepared at the time, does not record any mention of Mohamed Atta or any of the other future hijackers, or any suggestion that their identities were known to anyone at DOD before 9/11. Nor do any of the three Commission staffers who participated in the interview, or the executive branch lawyer, recall hearing any such allegation. -

Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community

TILL DEATH DO US PART: PREPUBLICATION REVIEW IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY Kevin Casey* As a condition of access to classified information, most employees of the U.S. intelligence community are required to sign nondisclosure agreements that mandate lifetime prepublication review. In essence, these agreements require employees to submit any works that discuss their experiences working in the intelligence community---whether writ- ten or oral, fiction or nonfiction---to their respective agencies and receive approval before seeking publication. Though these agreements constitute an exercise of prior restraint, the Supreme Court has held them constitu- tional. This Note does not argue fororagainsttheconstitutionality of prepublication review; instead, it explores how prepublication review is actually practiced by agencies and concludes that thecurrentsystem, which lacks executive-branch-wide guidance, grants too much discretion to individual agencies. It compares the policies of individual agencies with the experiences of actual authors who have clashed with prepublication-review boards to argue that agencies conduct review in a manner that is inconsistent at best, and downright biased and discriminatory at worst. The level of secrecy shrouding intelligence agencies and the concomitant dearth of publicly available information about their activi- ties make it difcult to evaluate their performance and, by extension, the performance of our electedofcials in overseeing such activities. In such circumstances, memoirs and other forms of expression -

The Rise of Radical Islam and Effectiveness of Counter-Terrorism in a Global Age Written by Zaki Mehta

The Rise of Radical Islam and Effectiveness of Counter-Terrorism in a Global Age Written by Zaki Mehta This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The Rise of Radical Islam and Effectiveness of Counter- Terrorism in a Global Age https://www.e-ir.info/2011/09/20/the-rise-of-radical-islam-and-effectiveness-of-counter-terrorism-in-a-global-age/ ZAKI MEHTA, SEP 20 2011 Terrorism, one may argue, has existed for as long as man himself. Regardless of its aims, terrorism has throughout time continually changed in form due to ever changing factors such as; the perpetrators, means, motivation and the victims. Subsequently so have the methods with which to counter terrorism. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century there has been a stark shift in the global perception of terrorism and its cause. As a consequence of such a shift it is fair to say that there has been a direct change in the measures taken in order to halt terrorism. This dissertation seeks to discuss the origins and rise of radical Islam as the new so called ‘terror’ and the subsequent development and transition of counter-terrorism in the post September 11th 2001 period. Specifically, this essay seeks to discuss the development of counter-terrorism in relation to the pivotal concept of radical Islam. Rightly or wrongly radical Islam is perceived as the modern day global ‘terror’ and it will be used in this dissertation in order to assess the evolution of counter-terrorism in the twenty first century. -

ENDNOTES Endnotes

CHAPTER 1 ENDNOTES Endnotes 1 Guantánamo Remarks Cost Policy Chief His Job, CNN (Feb. 2, 2007), available at http://www.cnn. com/2007/US/02/02/gitmo.resignation (“When corporate CEOs see that those firms are representing the very terrorists who hit their bottom line back in 2001, those CEOs are going to make those law firms choose between representing terrorists or representing reputable firms.”). 2 Task Force staff interview with Moazzam Begg, Omar Deghayes, Bisher al-Rawi (Apr. 17, 2012) [hereinafter Begg, Deghayes, al-Rawi Interview]. 3 Neil A. Lewis, U.S. Military Eroding Trust of Detainees, Lawyers Say, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 9, 2005), available at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/08/world/americas/08iht-gitmo.html (“Another lawyer, Marc Falkoff of New York, whose firm represents several Yemenis at the naval base in Cuba, said some of his clients had told him that a person who said he was a lawyer and had civilian clothes had conferred several times with some detainees. That person, Falkoff said his clients had told him, later appeared at the detention center in uniform, leading the inmates to distrust anyone claiming to be a lawyer and acting in their interest.”). See also Neil A. Lewis, Detainee’s Lawyer Says Captors Foment Mistrust, N.Y. TIMES (Dec. 7, 2005), available at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/07/international/07hamdan.html (“The Guantánamo authorities violated a court order by moving a prisoner from the general population there and placing him in close contact with a hard-core operative for Al Qaeda known for urging detainees to refuse to cooperate with their lawyers, according to papers filed with the United States District Court here by Lt.