Proceedings of the 1990 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facility / Approx. Distance & Time by Car Address Town Phone# Website

Facility / Approx. Distance & Time by Car Address Town Phone# Website Berlin NH Gorham NH (6 miles / 11 minutes) Dolly Copp Rt 16 Gorham, NH 03581 603‐466‐2713 www.reserveamerica.com Moose Brook State Park 32 Jimtown Road Gorham, NH 03581 603‐466‐3860 www.reserveamerica.com Milan NH (8 miles / 14 minutes) Cedar Pond Campground 265 Muzzy Hill Road Milan, NH 03588 603‐449‐2240 www.cedarpondcamping.com Deer Mountain Lodge 1442 Route 16 Dummer, NH 03588 603‐723‐9756 www.deermountainlodge.com Milan Hill State Park Milan Hill Milan, NH 03588 603‐449‐2429 www.nhstateparks.org Shelburne NH (12 miles / 19 minutes) Timberland Campground Route 2 Shelburne, NH 03581 603‐466‐3872 [email protected] White Birches Campground Route 2 Shelburne, NH 03581 603‐466‐2022 www.whitebirchescamping.com Jefferson NH (29 miles / 37 minutes) Fort Jefferson Campground Route 2 Jefferson, NH 03583 603‐586‐4592 www.fortjeffersoncampground.com Israel River Campground 111 Israel River Rd Jefferson, NH 03583 603‐586‐7977 www.israelrivercampground.com The Lantern Resort Motel & Campground Route 2 Jefferson, NH 03583 603‐586‐7151 www.thelanternresort.com Lancaster NH (30 miles / 38 minutes) Beaver Trails Campground 100 Bridge Street Lancaster, NH 03584 888‐788‐3815 www.beavertrailsnh.com Mountain Lake Campground & Log Cabins Route 3 Lancaster, NH 03584 603‐788‐4509 www.mtnlakecampground.com Roger's Campground and Motel Route 2 Lancaster, NH 03584 603‐788‐4885 www.rogerscampground.com Twin Mountain NH (30 miles / 38 minutes) Ammonoosuc Campground Twin Mountain, -

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors Dartmouth/Lake

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors www.NHGraniteStateAmbassadors.org Regional Resource & Referral Guide: Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region Use this document filled with local referrals from Granite State Ambassadors & State Welcome Center attendants as an informational starting point for guest referrals. For business referrals, please reference your local brochures & guides. Hidden Gems ● Grafton Pond, Grafton Pond Rd, Grafton – 319 acre pond and accompanying reservation, abundant wildlife, including loons; no motor boats, no road noise, and very little shore development. Kayaking and canoeing allowed. Hiking trails. (https://forestsociety.org/property/grafton-pond-reservation) ● La Salette Shrine Light Display, 410 NH 4A, Enfield – 20-acre hillside display with tens of thousands multicolored Christmas lights, Thanksgiving to Christmas. Worship services held all year. Free. (http://www.lasaletteofenfield.org/) ● Maxfield Parrish Stage Backdrop, Plainfield Town Hall, NH 12°, Plainfield – Painted by Parrish in 1916. Call the town hall for viewing times: (603) 469-3201. (https://www.crjc.org/heritage/N09-2.htm for info on backdrop) Curiosity ● View of Grantham Mountain, I-89 Northbound, Springfield – Grantham Mountain remains barren of vegetation at the top where in 1953 a long lasting fire raged for many days. The exposed soil quickly eroded away, exposing the gray ledges of . granite underneath. Good view from back door of Springfield Welcome Center. Covered Bridges – For complete descriptions and map visit (https://www.nh.gov/nhdhr/bridges/table.html) ● Bement Bridge, Bradford Center Rd., Bradford – South of junction NH 103 and 114 ● Blacksmith Bridge, Town House Rd., Cornish – 2 miles east of NH 12A ● Blow Me Down Bridge, Mill Rd., Cornish – south of NH 12A, 1½ mile southwest of Plainfield ● Brundage, Off Mill Brook, East Grafton – pedestrians only, private property. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Page A13 - 1 DRED - Division of Parks and Recreation STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT and CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PLAN, 2009 Appendix 13 - Division Fee Schedule and Discounts

DRED - Division of Parks and Recreation STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT and CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PLAN, 2009 Appendix 13 - Division Fee Schedule and Discounts DEPARTMENT of RESOURCES and ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION of PARKS and RECREATION Calendar 2009/2010 Rates in parenthesis represents previous year prices *denotes new products I. Standard Park Pricing Adult Fee Youth Fee Child NH Resident NH Resident a) Day-Use Fees (Ages 12 -64) (Ages 6 - 11) (Ages 0-5) Senior Wednesdays w/ticketed adult (65 & older) Single Day Visit $4.00 $2.00 $0.00 $0.00 $2.00 - Adults Car Parking (Hampton/Wallis) $15.00 N/A $0.00 $0.00 $7.50 Historic Sites $7.00 $3.00 $0.00 $0.00 FREE - Everyday * Discovery Pass (Cannon/Flume) $24.00 $18.00 $0.00 $0.00 N/A Flume Gorge $13.00 ($12.00) $9.00 ($8.00) $0.00 $0.00 N/A 1. Self-Pay Locations (In the absence of an attendant, fees charged and submitted in an envelope specific to number of guest). Bear Brook Milan Moose Brook Coleman Molidgewock Pawtuckaway CNSP-Dry River Monadnock Pillsbury Deer Mountain Old Toll Rd Trailhead Sunapee Franconia (Hiker Lot) Dublin Trailhead Umbagog Greenfield No.& So. Gap Trailhead White Lkae Lake Francis 2. Donations (Non-specific amounts given purely as contribution). Crawford Notch (Willey Hse.) Rollins Lafayette Place Rhododendron Miller Wadleigh Odiorne (boat launch) Winslow Rye Harbor (Ragged Neck) (The Division reserves the right to add self-pay stations throughout the state park system pursuant to RSA 216-A:3) b) Camping Fees Additional Additional NH Resident (Max. -

Campground Address Town Phone# Website Berlin NH Jericho

Campground Address Town Phone# Website Berlin NH Jericho Mountain State Park Route 110 Berlin NH www.reserveamerica.com Gorham NH (6 miles / 11 minutes) Moose Brook State Park 32 Jimtown Road Gorham NH 603‐466‐3860 www.reserveamerica.com Dolly Copp Rt 16 Gorham NH 603‐466‐2713 www.reserveamerica.com Milan NH (8 miles / 14 minutes) Cedar Pond Campground 265 Muzzy Hill Road Milan NH 603‐449‐2240 www.cedarpondcamping.com Milan Hill State Park Milan Hill Milan NH 603‐449‐2429 www.nhstateparks.org Deer Mountain Lodge 1442 Route 16 Dummer 603‐723‐9756 www.deermountainlodge.com Shelburne NH (12 miles / 19 minutes) White Birches Campground Route 2 Shelburne NH 603‐466‐2022 www.whitebirchescamping.com Timberland Campground Route 2 Shelburne NH 603‐466‐3872 [email protected] Jefferson NH (29 miles / 37 minutes) The Lantern Resort Motel & Campground Route 2 Jefferson NH 603‐586‐7151 www.thelanternresort.com Fort Jefferson Campground Route 2 Jefferson NH 603‐586‐4592 www.fortjeffersoncampground.com Israel River Campground 111 Israel River Rd Jefferson NH 603‐586‐7977 www.israelrivercampground.com Lancaster NH (30 miles / 38 minutes) Mountain Lake Campground & Log Cabins Route 3 Lancaster NH 603‐788‐4509 www.mtnlakecampground.com Roger's Campground and Motel Route 2 Lancaster NH 603‐788‐4885 www.rogerscampground.com Beaver Trails Campground 100 Bridge Street Lancaster NH 888‐788‐3815 www.beavertrailsnh.com Twin Mountain NH (30 miles / 38 minutes) Beech Hill Campground & Cabins Route 302 Twin Mountain NH 603‐846‐5521 www.beechhill.com -

State of New Hampshire

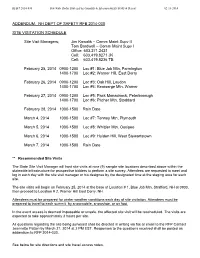

RFB # 2014-030 Statewide Radio System Functionality & Interoperability Study & Report 02-10-2014 ADDENDUM. NH DEPT OF SAFETY RFB 2014-030 SITE VISITATION SCHEDULE Site Visit Managers; Jim Kowalik – Comm Maint Supv II Tom Bardwell – Comm Maint Supv I Office: 603.271.2421 Cell: 603.419.8271 JK Cell: 603.419.8236 TB February 25, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #1: Blue Job Mtn, Farmington 1400-1700 Loc #2: Warner Hill, East Derry February 26, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #3: Oak Hill, Loudon 1400-1700 Loc #4: Kearsarge Mtn, Warner February 27, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #5: Pack Monadnock, Peterborough 1400-1700 Loc #6: Pitcher Mtn, Stoddard February 28, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date March 4, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #7: Tenney Mtn, Plymouth March 5, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #8: Whittier Mtn, Ossipee March 6, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #9: Holden Hill, West Stewartstown March 7, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date ** Recommended Site Visits The State Site Visit Manager will host site visits at nine (9) sample site locations described above within the statewide infrastructure for prospective bidders to perform a site survey. Attendees are requested to meet and log in each day with the site visit manager or his designee by the designated time at the staging area for each site. The site visits will begin on February 25, 2014 at the base of Location # 1, Blue Job Mtn, Strafford, NH at 0900, then proceed to Location # 2, Warner Hill East Derry, NH. Attendees must be prepared for winter weather conditions each day of site visitation. Attendees must be prepared to travel to each summit by snowmobile, snowshoe, or on foot. -

Parks for Kids

new hampshire parks for kids 1. Franconia Notch State Park Learn about Notch’s history at the visitor cen- ter, then hike into Flume Gorge. Go swimming in Echo Lake and visit the Basin. End the trip with a ride on the Aerial Tramway and marsh- mallows by a campfire. Buddy Bison’s Fact Bites! 2. Mount Washington State Park Hike the Alpine Garden Trail to see alpine flowers and stop by the Tip-Top House historic • The first public library in the hotel. Be sure to check out the observatory United States was founded in and catch the view from the top of New En- gland’s highest mountain! Peterborough in 1833. 6. White Lake State Park Go canoeing or kayaking, have fun on the • The state’s motto is “Live Free 3. Odiorne Point State Park playground, go swimming or fishing in the gla- cial lake, then spend the night camping! or Die.” Of the thirteen original Discover marine life in the Seacoast Science colonies, New Center and look through the tide pools of the Sunken Forest to spot sea urchins and crabs. www.parktrust.org Hampshire was the first to de- Hike to Frest Point and fish off the jetty. 7. Monadnock State Park clare independence. Hike one of the many trails and bring some snacks for a picnic. In the winter, try snowshoe- ing or cross-country skiing! Camp overnight. • New Hampshire is known as the 4. Saint-Gaudens National “Granite State,” referring to its Historic Site vast granite formations, and the Complete the Valley Quest program, then hike 8. -

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors Great North Woods

New Hampshire Granite State Ambassadors www.NHGraniteStateAmbassadors.org Regional Resource & Referral Guide: Great North Woods Region Use this document filled with local referrals from Granite State Ambassadors & State Welcome Center attendants as an informational starting point for guest referrals. For business referrals, please reference your local brochures & guides. Hidden Gems: ● Baby Flume Gorge, 1212 NH 26 West, Dixville Notch – short walk inside Dixville Notch State Park to a waterfall within a small, narrow gorge. The Cascade Brook Falls are across the road about ¼ mile. (https://www.nhstateparks.org/visit/state-parks/dixville-notch-state- park) ● Beaver Brook Falls, NH 145, Colebrook – About 2.5 miles north of Colebrook on the right- hand side of the road. (https://www.chamberofthenorthcountry.com/blog/best-bets-north- country-waterfalls) ● Pondcherry Wildlife Refuge, Airport Rd., Whitefield – Off NH 115, hiking trails, owned and managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in partnership with NH Audubon and NH Department of Fish and Game. (http://www.nhaudubon.org/pondicherry-wildlife-refuge/) ● Lake Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge and NH 16 North along the Thirteen Mile Woods for moose watching and beautiful landscapes. (https://www.fws.gov/refuge/umbagog/) Curiosity: ● North Hill Cemetery, off NH 145, Stewartstown Hollow in Stewartstown – Grave of Metallak was the last Indian living in NH who had not gone to Canada or assimilated into early 19th century American culture. https://www.chamberofthenorthcountry.com/historical- attractions.html) ● 45th Parallel, NH 145, Clarksville – Located in triangular plot at junction of NH 145 and Clarksville Pond Road. At this point you stand at longitude 71 degrees, 24 degrees west from Greenwich, England and half-way between the equator and the north pole. -

News from the Selectboard Labor Day, Monday September

Volume 9 Published monthly since May 1999 September 2015 News from the Selectboard Erik Spitzbarth, Chairman for the Selectboard APPOINTMENTS AND RECOGNITIONS: The BOS approved the following appointments: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE WATER in Norway Pond Contoocook River Advisory – Kenneth Messina, is a science experiment in the making. The self Zoning Board Alternate – Jeff Reder, energizing cynobacteria bloom that was detected relies Cemetery Trustee – Dennis Rossiter (for balance of open on sunlight to drive the process of photosynthesis, 2017 term), absorbing (fixing) CO² and using water as an electron donor that produces oxygen as a byproduct…all essential Historic District Commission – Fred Heyliger, to our well being and life on earth. That being said, we Old Home Days Committee – Melody Russell 3 yr term don’t necessarily want to swim in it. :( The board expresses special appreciation and accolades The town contracts water testing three times during the to the OHD committee, Recreation Committee, Fire De- summer for concentrations of Oscillatoria with the partment, and the many helping hands that volunteered Department of Environmental Services (DES). Our their time and talents in making this year’s “New Life for physical observation of a “bloom” situation initiated an Old Treasures” another success. additional test that confirmed we had approached a “no “KEEPING YOUR HEAD ABOVE WATER” swimming” advisory. Our safe guarding process had gave new meaning to the Synchro Sistahs: worked. For those that want to know more about Adine Aldrich, Alex Murray-Golay, Amy Markus, cynobacteria, search the web or go to the DES website: Barbara Schweigert, Cynthia Nichols, Jan Buonanno, http://des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/water/wmb/ Jess Codman (choreographer),Julie Brown, Lizzy Cohen, beaches/faq_cyanobacteria.htm Sadie Faber, and Tracy Grissom as they performed at the Fake Lake due to Norway Pond’s last minute closing to swimmers! Special kudos go out to the “Sistahs” for continuing their performance and showing us true grit and belief in “the show must go on”. -

Lakes Region Tourism Profile 2002

Lakes Region Tourism Profile Lakes Region Planning Commission January 2002 Lakes Region Planning Commission Lakes Region Tourism Profile Prepared by the Lakes Region Planning Commission 103 Main Street, Suite #3 Meredith, New Hampshire 03253 This report was prepared under contract with New Hampshire Community Development Finance Authority and the Belknap County Economic Development Council Opinions in this report are not necessarily those of the grantor agencies LRPC COMMISSIONERS 2001-2002 ALTON BRIDGEWATER EFFINGHAM HEBRON MOULTONBOROUGH SANDWICH Alan Sherwood Vacant William Stewart Vacant Terence Jatko Toby Eaton James Washburn Janet Normandeau Jeremiah V. Donovan Thomas Hoopes, Alt. ANDOVER BRISTOL FRANKLIN HILL NEW HAMPTON TAMWORTH Eric A. Johnson David Sullivan Thomas Bugely Vacant Dr. George Luciano Herb Cooper Kevin S. Sleeper Michael Soule Norma Schofield Paul Tierney Robert Freeto ASHLAND BROOKFIELD FREEDOM HOLDERNESS NORTHFIELD TILTON Christopher Johnstone Anne Martin Robert Houle Robert Snelling Francis LaBranche Katherine Dawson Ralph Kazanjian Adam Tatem David Krause Robert Brown Douglas Read, Alt. BARNSTEAD CENTER HARBOR GILFORD LACONIA OSSIPEE WOLFEBORO William Evans Harold Tate Richard Waitt Arthur Abelmann Dr. Patricia Jones Roger Murray, III Harold Bernt Peter Brunette Mark McConkey William Wiebe David Stamps BELMONT DANBURY GILMANTON MEREDITH SANBORNTON Donald Pugh Phyllis J. Taylor George Twigg, III William Bayard Earl Leighton, Jr. William Brunkhardt Stanley O. Bean, Jr. Herbert Vadney Patricia Shattuck LAKES REGION PLANNING COMMISSION STAFF Kimon G. Koulet Executive Director Kristen Michaelides Regional Planner Peer Kraft-Lund Senior Planner Nancy Johnson Project Planner Greg Tansley Principal Planner Thomas Smith General Program Assistant Michael Izard Regional Planner Barbara J. Perry Administrative Assistant S. Robin McCann Regional Planner Karen Peranelli Bookkeeper TABLE OF CONTENTS page Executive Summary i I. -

Biennial Report Forestry Division

iii Nvw 3Jtampstin BIENNIAL REPORT of the FORESTRY DIVISION Concord, New Hampshire 1953 - 1954 TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT TO GOVERNOR AND COUNCIL 3 REPORT OF THE FORESTRY DIVISION Forest Protection Forest Fire Service 5 Administration 5 Central Supply and Warehouse Building 7 Review of Forest Fire Conditions 8 The 1952 Season (July - December) 8 The 1953 Season 11 The 1954 Season (January - June) 19 Fire Prevention 21 Northeastern Forest Fire Protection Commission 24 Training of Personnel 24 Lookout Station Improvement and lVlaintenance 26 State Fire Fighting Equipment 29 Town Fire Fighting Equipment 30 Radio Communication 30 Fire Weather Stations and Forecasts 32 Wood-Processing Mill Registrations 33 White Pine Blister Rust Control 34 Forest Insects and Diseases 41 Hurricane Damage—1954 42 Public Forests State Forests and Reservations 43 Management of State Forests 48 State Forest Nursery and Reforestation 53 Town Forests 60 White Mountain National Forest 60 Private Forestry County Forestry Program 61 District Forest Advisory Boards 64 Registered Arborists 65 Forest Conservation and Taxation Act 68 Surveys and Statistics Forest Research 68 Forest Products Cut in 1952 and 1953 72 Forestry Division Appropriations 1953 and 1954 78 REPORT OF THE RECREATION DIVISION 81 Revision of Forestry and Recreation Laws j REPORT To His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council: The Forestry and Recreation Commission submits herewith its report for the two fiscal years ending June 30, 1954. This consists of a record of the activities of the two Divisions and brief accounts of related agencies prepared by the State Forester and Director of Recrea tion and their staffs. -

Kingston State Park Beach 29 Hazen Drive, Concord, New Hampshire 03301 • (603) 271‐3503 •

Kingston State Park Beach 29 Hazen Drive, Concord, New Hampshire 03301 • (603) 271‐3503 • www.des.nh.gov Beach Sampling Program To protect the public from possible illness while swimming, each summer the NH Beach Program monitors water from 193 beaches for fecal bacteria. When fecal bacteria levels exceed state standards, harmful organisms are likely growing in the water making the water unsafe for swimming. When fecal bacteria levels are high, DES issues an advisory. Signs are posted at beach entry points. Alerts are placed on the DES webpage. The water is resampled daily until the bacteria levels are below state standards and the advisory is removed at that time. Likelihood the water is clean 193 New Hampshire beaches display 100% this sign indicating participation in the DES Beach Inspection Program 95% 94% 80% 86% Sampling at Kingston State Park Beach 77% Owner: NH Division of Parks & Recreation 60% 65% Waterbody: Great Pond, Kingston Chance (%) Chance 55% Sampling Visits Each Season: 3 40% Samples Collected since 2003: 110 Samples Above State Standard: 7 20% Advisories from 2003-2012: 3 Wellington Kingston Wentworth Ellacoya Bear Brook Pawtuckaway Advisories in 2013: 0 State Park Beach How clean has the beach been over time? By comparing how many fecal bacteria samples have been below the state standard with all samples collected at a beach, a prediction can be made. At Beach Advisory Postings Kingston State Beach, out of every 100 samples collected, 94 are The NH Beach Program posts expected to be good. Compared to five popular state park beaches, advisories discouraging contact with Kingston State Beach is more likely to have clean samples than all the water.