Village Survey Monographs, Part VI, Volume-IV, Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Report After Every General

Cabinet (Election) Department Near Gayatri Mandi, H.E.C., Sector-2 Dhurwa, Ranchi-834004 From the desk of Chief Electoral Officer It is customary to bring out a Statistical Report after every General Election setting out the data on the candidates and the votes polled by them besides information on electorate size and polling stations etc. The present Report presents the statistics pertaining to the General Election to Jharkhand Assembly Constituency 2014. It is hoped that the statistical data contained in this booklet will be useful to all those connected with, or having an interest in, electoral administration, and politics and for researchers. (P.K. Jajoria) Chief Electoral Officer CONTENTS Sl. No. Item Page No. 1 Schedule of General Election to Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 2014 2 Re-poll Details 3 District Election Officers 4 Assembly Constituency wise Returning Officers 5 Assembly Constituency wise Assistant Returning Officers 6 Highlights 7 List of Political Parties That Contested The General Election 2014 To Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 8 Number, Name and Type of Constituencies, No. of Candidates per Constituency, List of Winners with Party Affiliation 9 Nomination Filed, Rejected, Withdrawn And Candidates Contested 10 Number of Cases of Forfeiture of Deposits 11 Performance of Political Parties And Independents 12 Performance of Women Candidates 13 Assembly Constituency Wise Electors 14 Assembly Constituency wise details of Photo Electors, EPIC holders and percentages. 15 Assembly Constituency Wise Electors And Poll Percentage -

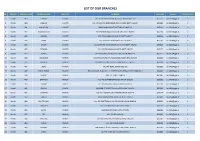

List of Our Branches

LIST OF OUR BRANCHES SR REGION BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME DISTRICT ADDRESS PIN CODE E-MAIL CONTACT NO 1 Ranchi 419 DORMA KHUNTI VILL+PO-DORMA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 2 Ranchi 420 JAMHAR KHUNTI VILL-JAMHAR,PO-GOBINDPUR RD,VIA-KARRA DISTT-KHUNTI. 835209 [email protected] 0 3 Ranchi 421 KHUNTI (R) KHUNTI MAIN ROAD,KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 210 835210 [email protected] 0 4 Ranchi 422 MARANGHADA KHUNTI VILL+PO-MARANGHADA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 5 Ranchi 423 MURHU KHUNTI VILL+PO-MURHU,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835216 [email protected] 0 6 Ranchi 424 SAIKO KHUNTI VILL+PO-SAIKO,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 7 Ranchi 425 SINDRI KHUNTI VILL-SINDRI,PO-KOCHASINDRI,VIA-TAMAR,DISTT-KHUNTI 835225 [email protected] 0 8 Ranchi 426 TAPKARA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TAPKARA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835227 [email protected] 0 9 Ranchi 427 TORPA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TORPA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 10 Ranchi 444 BALALONG RANCHI VILL+PO-DAHUTOLI PO-BALALONG,VIA-DHURWA RANCHI 834004 [email protected] 0 11 Ranchi 445 BARIATU RANCHI HOUSING COLONY, BARIATU, RANCHI P.O. - R.M.C.H., 834009 [email protected] 0 12 Ranchi 446 BERO RANCHI VILL+PO-BERO, RANCHI-825 202 825202 [email protected] 0 13 Ranchi 447 BIRSA CHOWK RANCHI HAWAI NAGAR, ROAD NO. - 1, KHUNTI ROAD, BIRSA CHOWK, RANCHI - 3 834003 [email protected] 0 14 Ranchi 448 BOREYA RANCHI BOREYA, KANKE, RANCHI 834006 [email protected] 0 15 Ranchi 449 BRAMBEY RANCHI VILL+PO-BRAMBEY(MANDER),RANCHI-835205 835205 [email protected] 0 16 Ranchi 450 BUNDU -

Officename Chanda B.O Mirzachowki S.O Boarijore B.O Bahdurchak B.O

pincode officename districtname statename 813208 Chanda B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Mirzachowki S.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Boarijore B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bahdurchak B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Beniadih B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bhagmara B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bhagya B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Chapri B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Mandro B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Maniarkajral B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Mordiha B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Rangachak B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Sripurbazar B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Thakurgangti B.O Godda JHARKHAND 814101 Bandarjori S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 S.P.College S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 Dumka H.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 Dumka Court S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Amarapahari B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bhaturia B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Danro B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Sinduria B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Ramgarah S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Gamharia B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bandarjora B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bariranbahiyar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bhalsumar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Chhoti Ranbahiyar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Ghaghri B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Kakni Pathria B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Khudimerkho B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Kairasol B.O Godda JHARKHAND 814102 Lakhanpur B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Mahubana B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Piprakarudih B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Sushni B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Kathikund S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Saldaha B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Sarsabad B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Kalajhar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 T. Daldali B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Astajora B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Pusaldih B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Amgachi B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 B. -

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME of SCHOOL

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL District: RANCHI 80100510 20140117617 A G CHURCH HIGH SCHOOL RANCHI 80100376 20140105605 A G CHURCH MIDDLE SCHOOL KANKE HUSIR 80100383 20140106203 A G CHURCH SCHOOL FURHURA TOLI 80100806 20140903803 A G CHURCH SCHOOL 80100917 20140207821 A P E G RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL RATU 80100808 20140904002 A Q ANSARI URDU MIDDLE SCHOOL IRBA 80100523 20140119912 A S PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100524 20140120009 A S T V S ZILA SCHOOL 80100411 20140109003 A V K S H S 80100299 20140306614 AADARSH GRAMIN PUBLIC SCHOOL TANGAR 80100824 20140906303 ADARSH BHARTI PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL MANDRO 80100578 20142401811 ADARSH H S MCCLUSKIEGANJ 80100570 20142400503 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL SANTI NAGAR KHALARI 80100682 20142203709 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL KOLAMBI TUSMU 80100956 20141108209 ADARSH UCHCHA VIDYALAYA MURI 80100504 20140116916 ADARSHA VIDYA MANDIR 80100846 20140913601 ADARSHHIGH SCHOOL PANCHA 80100214 20140603012 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA JINJO THAKUR GAON 80100911 20140207814 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA RATU 80100894 20140202702 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TIGRA GURU RATU 80100119 20140704204 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TUTLO NARKOPI 80100647 20140404507 ADIWASI VIKAS HIGH SCHOOL BAJRA 80101106 20140113028 AFAQUE ACADEMY 80100352 20140100813 AHMAD ALI MORDEN HIGH SCHOOL 80100558 20140123620 AL-HERA PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100685 20142203716 AL-KAMAL PLAY HIGH SCHOOL 80100332 20142303514 ALKAUSAR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ITKI RANCHI 80100741 20140803807 AMAR JYOTI MIDDLE CUM HIGH SCHOOL HARDAG 80100651 20140404516 -

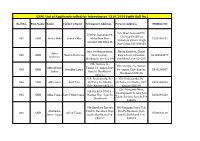

GNM: List of Applicants Called for Interview on 13.01.2019 (With Roll No.)

GNM: List of Applicants called for Interview on 13.01.2019 (with Roll No.) Roll No. Post Name Name Father's Name Permanent Address Present Address MOBILE NO C/o Heart Sospital PVt. Vill+PO- Rajoanda PS- LTd Opp Kendriiya 001 GNM Amita Ekka Simon Ekka Mahudana Dist- 7250148151 Vidyalaya Kankar Bagh Latehar PIN-822119 Dist- Patna PIN-800020 Jata, Ps-Mahuadanar, Binita Kerketta, Christ Abha 002 GNM Martin Kerketta Dist- latehar, Raja School, Chandwa, 91133553977 Kerketta Jharkhand, Pin-822199 Jharkhand, Pin-829203 Vill- Doreya, Po- Vill- Doreya, Po- Tamar, Abha Nutan Tamar, Ps- tamar, Dist- 003 GNM Jowakim Lakra Ps- tamar, Dist- Ranchi, 8340269597 Lakra Ranchi, Jharkhand- Jharkhand-835225 835225 Vill- Bada pandu, Po- Vill- Bada pandu, Po- 004 GNM Abha Rani Asaf Tiru Bichana, Ps- Murhu, Bichana, Ps- Murhu, Dist- 8340184096 Dist- Khunti-835210 Khunti-835210 C/o- Margaret Minz, Vill-Kurkura PO+PS - Jandraprasth Colony Jora 005 GNM Abha Toppo Late Philip toppo Mandar Dist - Ranchi 8102099288 Talab, Bariatu, Ranchi, Pin- ,Jharkhand 834009 Vill-Kamdara Bar toli Vill-Namkum Patra Toli, Abhilasha ,PO+PS- Kamdara ,Dist- PO+PS-Namkum, Dist- 006 GNM Alfred Toppo 8789091119 Sanes Toppo Gumla Jharkhand,Pin- Ranchi Jharkhand, Pin- 835227 834010 Vill- Bobro, Po- Charki Vill- Bobro, Po- Charki Agneshita Late Bensent Dumri, Ps- mandar, Dumri, Ps- mandar, Dist- 007 GNM 7762843072 Bara Bara Dist- Ranchi, Jharkhand- Ranchi, Jharkhand- 835301 835301 Ramnagar, Road No- Ramnagar, Road No-7/B, 7/B, hari mandir, Near hari mandir, Near Kartick 008 GNM Ajay Tanti -

Page 1 of 103 GN-29, SECTOR-V, SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF HEALTH SERVICES NURSING SECTION SWASTHYA BHAWAN, 1ST FLOOR, WING-A GN-29, SECTOR-V, SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA – 700091 No. HNG/3A-1-2018/Part-1/95 Date: 01/02/2019 ORDER The following Post Basic B.Sc (Nursing), B. Sc (Nursing) & GNM passed out candidates, recommended by West Bengal Health Recruitment Board are hereby appointed temporarily as Staff Nurse, Grade-II under W.B.N.S. Cadre in the Pay Band Scale of Rs. 7,100-37,600/- (minimum pay Rs. 7680/-) of Pay Band-3 with Grade Pay of Rs. 3,600/- related to WBS (ROPA) Rules, 2009 plus other allowances as admissible under existing Rules and posted at the Health Institutions as shown against their respective names in Column. No. 5 until further order. This appointment order has been issued on the basis of existing vacancies. This order will take immediate effect. SN Name Father's name & address Caste Place of Posting 1 2 3 4 5 North Bengal Medical PRAKASH THAPA, BELOW ST. MICHEAL SCHOOL, SHARON PRABHA College & Hospital, 1 P.O. NORTH POINT SINGAMARI, DARJEELING, OBC-B THAPA Darjeeling (Trauma Care 734104, WB Centre) BABLU SAHIS, RENY ROAD DHOBGHATA, KHEJURA Purulia District Hospital, 2 SUMAN KUMARI SC DANGA, PO-NAMOPARA, PURULIA, 723103, WB Purulia Infectious Disease & LOPAMUDRA NARAYAN SAHOO, E/P, 115 S.K.DEB ROAD,, OBC- 3 Beliaghata General SAHOO LAKETOWN, NORTH 24 PARGANAS, 700048, WB A Hospital, Kolkata REJABUL ALI SARKAR, VILL- ITAHAR, PO- ITAHAR, PS OBC- Marnai PHC, Itahar, 4 JEMIMA PARVIN - ITAHAR, UTTAR DINAJPUR, 733128, WB A Uttar Dinajpur Diamond -

Details of CSR Expenditure Incurred by IOCL During 2018-19

Details of CSR Expenditure incurred by IOCL during 2018-19 CSR Budget allocated for FY 2018-19: Rs.490.60 Crore Carry Forward from Previous year: Nil Total CSR budget for FY 2018-19: Rs.490.60 Crore Total CSR expenditure: Rs.490.60 Crore Amount spent on CSR Name of Project/ Activity Name of SI Activity/ Project (Rs. Description of Activity Village District State Implementing Agency in Lakh) Provision of 60 nos Solar Lights at Hope Town, Portblair, Andaman & Andaman WAAREE ENERGIES 1 Hope Town South Andaman 32.09 Nicobar Islands. Nicobar LIMITED Artificial Limbs Provision of aids and assistive devices to Divyangjans/Persons with Andhra 2 Guntakkal Anantapur Manufacturiong 40.62 Disabilities (PwDs) through ALIMCO. Pradesh corporation Ltd. Providing 150 nos. of Solar Street lights in 15 villages in Andhra Andhra Photonics, 3 15 Villages Chittoor 26.08 Pradesh Pradesh Gandhinagar SMART ANDHRA Installation of Advanced Digital Classrooms in Government Schools of Andhra 4 Kakinada East Godavari PRADESH 30.00 Andhra Pradesh. Pradesh FOUNDATION Construction of 02 nos 100 KL U/G Water Tanks along with Gummalladoddi, Andhra M/s LLC Infra Projects 5 East Godawari 22.85 submersible pump Kanupuru Pradesh Pvt. Ltd. , Hyderabad Provision of toilets and signages at Amaravathi Heritage Center and BHAVANI ISLAND Andhra 6 Museum (AHCM), Amaravathi, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh under Amaravathi Guntur TOURISM 40.00 Pradesh Swachh Iconic Tourist Places CORPORATION Artificial Limbs Provision of aids and assistive devices to Divyangjans/Persons with Andhra 7 Tadepalli Guntur Manufacturiong 59.61 Disabilities (PwDs) through ALIMCO. Pradesh corporation Ltd. Construction of Toilet block at Govt. -

Name of CSC Agent Sr.No

Name of CSC Agent Sr.No. Name of Bank Name of District Name of Block Locality / Village Name of BC / BCA Mobile No. of BC / BCA Base Branch Name (viz. UTL, Basix ) etc. 1 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Shivbabudih PremchaNd Kumar Bauri 8873701611 Amlabad GTDIS 2 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Amlabad SUBHASH KUMAR BAURI 8252937878 Amlabad GTDIS 3 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas BrahmaNdwarika SIDHESWAR GHOSAL 8084135076 CHAS BAZAR GTDIS 4 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Chandaha MANORANJAN MAHTO 8809957791 CHAS BAZAR GTDIS 5 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Devgram MANOJ KUMAR RAJWAR 9708668891 Amlabad GTDIS 6 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas KarhariYa SuNil Kumar 7763096033 BS City Ind GTDIS 7 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Gorabalidih (N) SaNjiv Kr SiNgh 9097367001 BS City Ind GTDIS 8 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Maraphari PuNarvas SaNju Kumari 9431508795 BS City Ind GTDIS 9 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(E) Ramesh Kr. RoY 9955183850 Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 10 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(S) Ramesh Kr. RoY Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 11 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(W) ShYam NaraYaN 8603704589 Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 12 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Paradih MD. HUZAIFA 7091919431 Chatra GTDIS 13 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Brahmana MD. HUZAIFA Chatra GTDIS 14 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Dumrikala TAWAN KUMAR RANA 8873827291 Dumri GTDIS 15 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Tarwagada VIJAY GANJHU 9931832523 Dumri GTDIS 16 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Kobna BireNdra Kumar Kushwaha 8298186267 Dumri GTDIS 17 United Bank of India Deoghar Deoghar SARSA SANJAY KUMAR YADAV 7739178238 RKMV GTDIS 18 United Bank of India Deoghar Deoghar GWALBADIA SURESH KUMAR YADAV 9199618993 Deoghar GTDIS 19 United Bank of India Deoghar Madhupur GONAIYA MritYuNja Kumar SiNgh 9334020288 Madhupur GTDIS 20 United Bank of India DhaNbad Tundi Rajabhita MD Aziz ANSARI 9693285868 Ojhadih GTDIS 21 United Bank of India DhaNbad Tundi KADAIYA Md. -

Gumla Circle Name & Shame List

Gumla Circle Name & Shame List Consumer Total Sno Type Consumer No Name Address Mobile Tariff Load Arrear Status PALKOT ROAD TR NO. 2 PALKOT ROAD TR NO. 2 1 OTHER 13919A ARVIND KR. SAHU GUMLA 0000000000 NDS-3 1 66801.09 Running RELIANCE 2 TOWER 160221025887 INFRATELLTD . NEW AZAD BASTI LOHARDAGA 0 0000000000 NDS-3 10 70571.85 Running JHARKHAND WOMEN SELF SUPPORT POETRY CO-OPERATIVE NA,NA,VILL+PO-BANAI,VILL+PO- 3 RULAR 20402 FEDERATION LIMITED BANAI,GUMLA,835229 0000000000 NDS-2 25 73209.32 Running S.D.E.(G) SIMDEGA 4 OTHER 3196 B.S.T POKLA GATE,KAMDARA 9470178936 NDS-2 8 160971.95 Running 5 TOWER 33620 BHARTI INFRATEL LTD BANAGUTU BASIA GUMLA 0000000000 NDS-2 12 208837.84 Running RELIANCE INFSATEL 6 TOWER 4133 LTD KONBIR NOATOLI BASIA GUMLA 6202532146 NDS-2 12 713075.85 Running KARAMBIR BHAGAT 7 OTHER 2324 S/O LT.B.BHAGA GHAGHRA, HAGHRA 9006027470 NDS-2 1 54132.54 Running GRAM JAL AWAM 8 OTHER 9516 SWACHHTA MANJIRA BISHUNPUR GHAGHRA, 0000000000 NDS-2 1 57563.22 Running MANTU KUMAR S/O 9 OTHER 2555 RAJ KISHOR SAH GHAGHRA CHANDNI CHOWK, HAGHRA 8789557028 NDS-2 1 60026.08 Running PANKAJ KR.SAHU S/O 10 OTHER 3285 SARJU PD.SA CHANDNI CHOWK,GHAGHRA, HAGHRA 8340335039 NDS-2 1 66657.13 Running 11 OTHER 15596 KHILESHWAR LOHARA KERAJHARIYA HOTEL, GHAGHRA GUMLA 8294459003 NDS-2 2 80653.59 Running THE MUKHIYA 12 OTHER 16533 BHANDARTOLI N.DIHA GRAM JAL SWAKSHTA, NAWDIHA 0000000000 NDS-2 2 83163.66 Running M/S KAYLESHWAR NATH, VIDYA MANDIR,GUNGA 13 OTHER 9540 RAJU KUMAR TOLI,BANARI 0000000000 NDS-2 2 144914.37 Running THE MANAGER 14 OTHER 744 CAFETENA -

Schedule for General Election to the Legislative Assembly of Jharkhand

ANNEXURE-1 Schedule Schedule for General Election to the Legislative Assembly of Jharkhand Poll Events Phase I Phase II Phase III Phase IV Phase V Date of Issue 06.11.2019 11.11.2019 16.11.2019 22.11.2019 26.11.2019 of Gazette Notification (Wednesday) (Monday) (Saturday) (Friday) (Tuesday) Last Date for 13.11.2019 18.11.2019 25.11.2019 29.11.2019 03.12.2019 making Nominations (Wednesday) (Monday) (Monday) (Friday) (Tuesday) Date for 14.11.2019 19.11.2019 26.11.2019 30.11.2019 04.12.2019 Scrutiny of Nominations (Thursday) (Tuesday) (Tuesday) (Saturday) (Wednesday) Last date for 16.11.2019 21.11.2019 28.11.2019 02.12.2019 06.12.2019 withdrawal of candidature (Saturday) (Thursday) (Thursday) (Monday) (Friday) Date of poll 30.11.2019 07.12.2019 12.12.2019 16.12.2019 20.12.2019 (Saturday) (Saturday) (Thursday) (Monday) (Friday) Date of 23.12.2019 23.12.2019 23.12.2019 23.12.2019 23.12.2019 Counting (Monday) (Monday) (Monday) (Monday) (Monday) Date of 26.12.2019 26.12.2019 26.12.2019 26.12.2019 26.12.2019 Completion (Thursday) (Thursday) (Thursday) (Thursday) (Thursday) 37 Annexure-1A List of 13 (Thirteen) Assembly Constituencies of Jharkhand going to poll in Phase-I PHASE-I Sl.No. Name of District No. and Name of Assembly Constituency 1. Chatra 27-Chatra (SC) 2. 68-Gumla (ST) Gumla 69-Bishunpur (ST) 3. Lohardaga 72-Lohardaga (ST) 4. 73-Manika (ST) Latehar 74-Latehar (SC) 5. 75-Panki 76-Daltonganj Palamu 77-Bishrampur 78-Chhatarpur (SC) 79-Hussainabad 6. -

List of Chargesheeted Public Servents Vigilance Bureau, Jharkhand, Ranchi

1 LIST OF CHARGESHEETED PUBLIC SERVENTS VIGILANCE BUREAU, JHARKHAND, RANCHI S Vigilance P.S Case no. – Related Accused Name And Designation No. Date & u/s Department 1 Vigilance P.S Case no Rural 1. Sri Rameswar Parasad, The then District 04/84 Dated 14.04.84 Development Relief Officer , Palamu (Retired) Under Section 5(2) r/w Department 2. Sri Luies Peter Surin, The then Director, section 5 (1) (d) P.C Act. & D.R.D.A D.R.D.A, Palamu .(Retired) 1947 3. Sri Krishnandan Prasad, the then Accountant, District Rural Development Agency (D.R.D.A) Palamu. 4. Sri Uma Shanker Prasad, The then head Clerk, District Relief Office, Palamu. 5. M/s Bharat Driling Ranchi, Proprietor Sri Jagdish Prasad S/O Rameswar Prasad At+Po – Simri- Bakhtiyarpur, Saharsha , Present- Ranchi Road, Morhabadi, Ranchi. 2 Vigilance P.S Case no Agriculture 1. Sri Jitendera Prasad Shukla, The then 48/89 Dated 26.10.89 Department Executive Engineer. Under Section 120 (b) / 2. Sri Ram Dular Chaubey The then Executive 420/409 I.P.C 5(2) r/w Engineer. section 5(1)(c)(d) P.C 3. Gopi Kant Chaudhari, The then Executive Act. 1947 r/w 13 (1) 13 Engineer. (2) (c)(d) I.P.C 1988 4. Sri Bhikhari Ram, The then, Assistant Engineer. 5. Sri Divaker Prasad Bidhyarthi, The then, Assistant Engineer. 6. Sri Krishan Kant Singh, The then, Assistant Engineer 267/C, Ashok Nager. 7. Sri Paras Nath Prasad, The then J.E, 8. Sri Revti Raman Batsalam, The then J.E 9. -

District Census Handbook Ranchi

GOVERNMENT OF BIHAR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK RANCHI By RANCHOR PRASAD, M.A., l.A S. Superintendent 0/ CellslIs Operations, HiI,aJ. PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT SECRETARIAT PRESS, BIHAR, PATNA 1956 ( Price-Rs. 5 ] TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface Population Map 1. Scheme of Tables-Census Tracts i-ii PART I 2. A-GENERAL POPULATION' TABLES- I-Area, Houses and Population 2 II-Variation in population during fifty years 3 III-Towns and villages classified by population 12 IV-Towns classified by population with variation since 1901 14 V-Towns arranged territorially with population by Livelihood Classes 15 3. B-EoONO!IIO TABLES- I-Livelihood Classes and Sub-Classes .. ' 18 II-;-Secondary means of livelihood 26 III-Employers, Employees and Independent workers .. 51 ·4. C-HOUSEHOLD AND AGE (SAMPLE) TABLES I-Household (Size and Composition) 82 II-Livelihood Classes by age-groups 84 III-Age and Civil conditions .. 87 IV-Age and Literacy 91 V-Single Year Age Returns 94 -5. D-SOCIAL AND CULTURAL TABLES I-Languages-(i) Mother tongue 99 (ii) Bilingualism 104 II-Religion 109 III-Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Backward and Non-Backward 112 Classes IV-Migrants 114 VII-Livelihood Classes by Educational Standards 117 6. E-SUMMARY FIGURES BY SUBDIVISIONS, REVENUE THANAS AND POLICE STATIONS 136 '7. ANALYSIS OF IMPORTANT CENSUS DATA- (1) Area and population, actual and percentage by Revenue Thana Density 144 (2) Variation and Density of General Population 144 (3) Mean Decennial Growth Rates during three decades 144 (4) Immigration .. 145 (5) Distribution of Population 1?etween villages 146 (6) Number per 1,000 of the Population and each Livelihood Class who" live 146 in Towns.