Kenya's Green Belt Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wangari Maathai

WANGARI MAATHAI Throughout Africa (as in much of the world) women hold primary responsibility for tilling the fields, deciding what to plant, nurturing the crops, and harvesting the food. They are the first to become aware of environmental damage that harms agricultural production: If the well goes dry, they are the ones concerned about finding new sources of water and who must walk long distances to fetch it. As mothers, they notice when the food they feed their family is tainted with pollutants or impurities: they can see it in the tears of their children and hear it in their babies’ cries. Wangari Maathai, Kenya’s foremost environmentalist and women’s rights advocate, founded the Green Belt Movement on Earth Day 1977, encouraging farmers (70 percent of whom are women) to plant “greenbelts” to stop soil erosion, provide shade, and create a source of lumber and firewood. She distributed seedlings to rural women and set up an incentive system for each seedling that survived. To date, the movement has planted more than fifteen million trees, produced income for eighty thousand people in Kenya alone, and has expanded its efforts to more than thirty African countries, the United States, and Haiti. Maathai won the Africa Prize for her work in preventing hunger, and was heralded by the Kenyan government—controlled press as an exemplary citizen. A few years later, when Maathai denounced President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi’s proposal to erect a sixty-two-story skyscraper in the middle of Nairobi’s largest park (graced by a four-story statue of Moi himself), officials warned her to curtail her criticism. -

Green Belt Movement of Kenya : a Gender Analysis

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2000 Green Belt Movement of Kenya : a gender analysis Wakesho, Catherine http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/1672 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Green Belt Movement of Kenya: A Gender Analysis BY CATHERINE WAKESHO DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY LAKEHEAD UNVERSITY THUNDER BAY, ONTARIO A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Masters of Arts ® Catherine Wakesho, 2000 ProQuest Number: 10611456 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Pro ProQuest 10611456 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 ABSTRACT The Green Belt Movement of Kenya is an environmental conservation movement that began in 1977 as a project of women planting trees. It has since grown into a popular movement in Kenya expanding its goals of environmental rehabilitation to include broader socio-political issues in the Kenyan context. To date the GBM has been the subject of studies, which have analysed various phases of its development. -

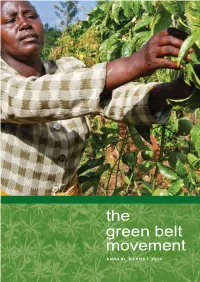

2015 Annual Report We Welcome You to Read the Stories of Change Embodied in Our Programmes and Projects, and the Partnerships That Have Enhanced the Way We Work

the green belt movement ANNUA L REPOR T 2015 1 | the green belt movement Annual Report 2014 “You cannot protect the environment unless you empower people, you inform them, and you help them understand that these resources are their own, that they must protect them.” — Professor Wangari Maathai, Founder, e Green Belt Movement 2 | the green belt movement Annual Report 2014 table of contents 3 A Message from the Board Chair 4 About the Green Belt Movement 6 Tree Planting and Water Harvesting 8 Climate Change 9 Corporate Partnerships 10 Gender, Livelihood and Advocacy 11 Outreach Updates — Kenya Updates from Green Belt Movement International — United Kingdom and U.S.A. 12 Financial Statements for 2015 15 Our Donors, Supporters and Partners 16 GBM Board and Sta Image Credits All photos © Green Belt Movement and Manoocher — USAID unless noted below. www.greenbeltmovement.orgwww.greenbeltmovement.org || 11 2 | the green belt movement Annual Report 2014 a message from the board chair Dear Friends, Over the past couple of years, I have had the pleasure of watching the resurgence at the Green Belt Movement. The transition, though dicult, has been a wonderful learning experience for us all. I am most humbled by the resilience of the team and their singular focus of keeping the legacy of our Founder, Professor Wangari Maathai, alive. In our 2015 Annual Report we welcome you to read the stories of change embodied in our programmes and projects, and the partnerships that have enhanced the way we work. In 2015, the Movement provided training to over 200 rural women and community-based organizations who have in turn trained over 20,000 members of their communities in natural resource management and impacted thousands of others. -

Download This Guide As A

TEACHER’S GUIDE The Story of Environmentalist Wangari Maathai written by Jen Cullerton Johnson, illustrated by Sonia Lynn Sadler About the Book SYNOPSIS Genre: Nonfiction Biography *Reading Level: Grade 6 As a young girl in Kenya, Wangari was taught to respect nature. She grew up loving the land, plants, and animals that surrounded her -- Interest Level: Grades 3–8 from the giant mugumo trees her people, the Kikuyu, revered to the Guided Reading Level: V tiny tadpoles that swam in the river. Accelerated Reader® Level/ Although most Kenyan girls were not educated, Wangari, curious Points: N/A and hardworking, was allowed to go to school. There, her mind sprouted like a seed. She excelled at science and went on to study Lexile™ Measure: N/A in the United States. After returning home, Wangari blazed a trail *Reading level based on the ATOS across Kenya, using her knowledge and compassion to promote the Readability Formula rights of her countrywomen and to help save the land, one tree at a time. Themes: AAfrican/African American Interest, Animal/Biodiversity/ The Story of Environmentalist Wangari Maathai brings to life the Plant Adaptations, Biography/ empowering story of Wangari Maathai, the first African woman, Memoir, Empathy/Compassion, and environmentalist, to win a Nobel Peace Prize. This chapter-book Environment/Nature, Human Impact edition includes black-and-white illustrations as well as sidebars on On Environment/Environmental Sustainability, Nonfiction, related subjects, a timeline, a glossary, and recommended reading. Occupations, Respect/Citizenship, Women’s History Teacher’s Guide copyright © 2019 LEE & LOW BOOKS. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to share and adapt for personal and educational use. -

Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt Movement

Women in African History Wangari maathai and the green belt movement UNESCO Series on Women in African History Women in African History The UNESCO Series on Women in African History, produced by the Knowledge Societies Division of UNESCO’s Communication and Information Sector, was conducted in the framework of the Priority Africa Intersectoral Platform, with the support of the Division for Gender Equality. This initiative was realized with the financial contribution of the Republic of Bulgaria. UNESCO specialist responsible for the project: Sasha Rubel Editorial and artistic direction: Edouard Joubeaud Published in 2014 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2014 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover illustration: Eric Muthoga Layout: Dhiara Fasya, Maria jesus Ramos Logo of the project: Jonathas Mello Wangari maathai and the green belt movement UNESCO Series on Women in African History Editorial and artistic direction: Edouard Joubeaud Comic strip Illustrations: Eric Muthoga Script and text: Obioma Ofoego Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt Movement Foreword The following comic strip is an interpretation of certain periods of the life of Wangari Maathai. -

Wangari Maathai: and the Green Belt Movement

Women in African History Wangari maathai and the green belt movement UNESCO Series on Women in African History Women in African History The UNESCO Series on Women in African History, produced by the Knowledge Societies Division of UNESCO’s Communication and Information Sector, was conducted in the framework of the Priority Africa Intersectoral Platform, with the support of the Division for Gender Equality. This initiative was realized with the financial contribution of the Republic of Bulgaria. UNESCO specialist responsible for the project: Sasha Rubel Editorial and artistic direction: Edouard Joubeaud Published in 2014 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2014 ISBN 978-92-3-100051-5 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily -

NGOCSD Draft 5-15-15 Wangari Celebration Program

Co CoNGO NGO Committee Committee on on Sustainable Sustainable Development, Development, NY NY Environmental,Environmental, social social and economicand economic development development that that meets meets the theneeds needs of theof thepresent present without without compromising compromising the abilitythe ability of future of future generations generations to meet to meet their their own own needs. needs. ~ “Turn~ “Turn Your Your Passions Passions into into Actions Actions for forCha Change”nge” ~ ~ NGOCSD General Membership Meeting: Friday, May 15th, 2015 ~ NGOCSD~ NGOCSD Members, Members, Colleagues Colleagues & Guests& Guests ~ ~ Nobel Laureate Professor Wangari Muta Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940 and was the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctorate degree. Wangari Maathai obtained a degree in Biological Sciences from Mount St. Scholastica College in WeAtchison, invite Kansas you (1964). to attendShe subsequently our Januaryearned a Master General of Science Membership degree from the University Meeting of Pittsburgh (1966). She pursued We idoctoralnvite studiesyou toin Germanyattend and our the UniversityJanuary of Nairobi,General obtaining Membership a Ph.D. (1971) from Meeting the University of Nairobi where she also taught veterinary anatomy. Ms. Maathai was active in the National Council of Women of Kenya from 1976-87 and was its chairman from 1981-87. During thisTuesday, time, she introduced January the idea27th of planting2015 trees~ Time: with the 2 people-4PM in 1976 and continued to develop it into a broad- based, grassrootsTuesday, organization January whose main 27th focus is2015 the planting ~ Time: of trees 2with-4 PMwomen groups in order to conserve the environment and improve their quality of life. -

Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE How does the simple act of planting trees lead to winning the Nobel Peace Prize? Ask Wangari Maathai of Kenya. In 1977, she suggested rural women plant trees to address problems stemming from a degraded environment. Under her leadership, their tree-planting grew into a nationwide movement to safeguard the environment, defend human rights and promote democracy. And brought Maathai the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. .org WWW.PBS.ORG/INDEPENDENTLENS/TAKINGROOT TAKING ROOT FROM THE FILMMAKERS We first met Wangari Maathai in the spring of 2002 at the Yale School worth and therefore any sense of the common good. For us, this was of Forestry. We were at once captivated and inspired by Wangari. We palpable in the Civic and Environmental Education Seminar that was grasped immediately that her vision for change and her methods for so brilliantly facilitated by Green Belt Movement staff. change were at one and the same time interknit in a dynamic that showed its power and effectiveness in the doing rather than in political When people arrived at the seminar, they were timid. Their bodies talking and ideology. She had the moral courage to speak truth to showed that they were fearful. At the end of the first day, they were power and the patience, persistence and commitment to take action - already changed; someone was listening to them. They discovered that against enormous odds. they held the answers to their own problems. A transformation was taking place before our eyes. In Wangari's story, we could see an evolutionary path that linked seemingly disparate realms. -

A Legacy Project the Wangari Muta Maathai House

a legacy project the Wangari Muta Maathai House Nairobi, Kenya November 2013 Wangari’s legacy Wangari Muta Maathai’s legacy takes many forms: the special qualities of her personality and vision; the lessons she took from her experiences; and the fortitude she displayed in speaking truth to power. In Kenya, she remains a symbol of hope and steadfastness. Her moral authority, resoluteness, and incorruptibility are truly missed by the ordinary people she championed and on behalf of whom she spoke. Throughout the world, she is remembered for her unwavering commitment to the global environment and the most marginalized people, particularly women. The loss of her strong voice and accessible presence has left a huge gap, particularly as nations and communities grapple with the realities of a changing climate. We, her friends, family and the extended Green Belt Movement family are dedicated to ensuring that her work and life are not forgotten, but that they continue to encourage people to live with conviction and courage. We believe that legacy projects are a vital way for people to honor Wangari’s memory, share experiences and be inspired by her life’s journey to take action. To that end, we are proposing the creation of the Wangari Muta Maathai House (WMM House): a sanctuary for reflection and renewal; a final home for her ashes; and a place of learning, growth, and action. 2 Origins: the essence of Wangari In the wake of Wangari’s death, her family and friends asked ourselves what aspects of Wangari we wanted to remember and spotlight. The following emerged: She was open and had time for everyone. -

Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor

4 Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor Ah, what an age it is / When to speak of trees is almost a crime / For it is a kind of silence about injustice! —Bertolt Brecht, “An die Nachgeborenen” (To posterity) Kenya’s Green Belt Movement, cofounded by Wangari Maathai, serves as an animating instance of environmental activism among poor communities who have mobilized against slow violence, in this case, the gradual violence of deforestation and soil erosion. At the heart of the movement’s activism stand these urgent questions: What does it mean to be at risk? What does it mean to be secure? In an era when sustainability has become a buzzword, what are the preconditions for what I would call “sustainable security”? And in seeking to advance that elusive goal, how can Maathai as a writer-activist working in conjunction with environmentally motivated women from poor communities, most effectively acknowledge, represent, and counter the violence of delayed effects? Maathai’s memoir, Unbowed, offers us an entry point into the complex, shifting collective strategies that the Green Belt Movement (GBM) devised to oppose foreshortened defi nitions of environmental and human security. What emerges from the GBM’s’s ascent is an alternative narrative of national slow violence, gender, and the environmentalism of the poor security, one that would challenge the militaristic, male version embodied and imposed by Kenya’s President Daniel arap Moi during his twenty-four years of authoritarian rule from 1978 to 2002. The Green Belt Movement’s rival narrative of national security sought to foreground the longer time- line of slow violence, both in exposing environmental degradation and in advancing environmental recovery. -

2014 Annual Report for the Green Belt Movement

the green belt movement A NNU AL R E P O R T 2 0 1 4 1 | the green belt movement Annual Report 2014 table of contents 3 A Message from the Board Chair 4 About the Green Belt Movement 6 Tree Planting and Water Harvesting 7 Corporate Partnerships 8 Climate Change 9 Gender, Livelihood and Advocacy 11 Outreach Updates — Kenya Updates from Green Belt Movement International — United Kingdom and U.S.A. 12 Financial Statements for 2014 15 Supporters and Partners 16 GBM Board and Staff 17 The Wangari Muta Maathai House — A Legacy Project “We owe it to ourselves and to the next generation to conserve the environment so that we can bequeath our children a sustainable world that benefits all.” — PROFESSOR WANGARI MAATHAI Image Credits Founder, The Green Belt Movement All photos © Green Belt Movement and Manoocher — USAID unless noted below. 2 | the green belt movement Annual Report 2014 www.greenbeltmovement.org | 1 a message from the board chair Dear Friends, I am delighted to present to you the 2014 Annual Report for the Green Belt Movement. It has been an inspiring year and one of continued resurgence. I owe the success stories you will read about in this report to the unwavering commitment and leadership of a delightful team of staff whose values and hard work continue to shine through. I must also salute the leadership of our Executive Director, Mrs. Aisha Karanja, who continues to increase the visibility of the Green Belt Movement. Tree planting for community mobilization and empowerment continues to be our focus. -

Wangari Maathai, an Inspiration – Curriculum

Curriculum to Teach about Wangari Maathai A Profile of Wangari Maathai: When I was a young person, I grew up in a land that was green, a land that was very pure, a land that was clean. And I remember going to a small stream very close to our homestead to fetch water and bring it to my mother. We used to drink that water straight from the river. I had this fascination with what I saw in the river. Sometimes I would see literally thousands of what looked like glass beads. I would put my little fingers around them in the hope that I would pick them and put them around my neck. But every time I tried to pick them, they disappeared. I would be there literally for hours desperately trying to pick these beads, without success. Weeks later I would come back, and there would be these thousands of little tadpoles. They are beautiful, pitch black, and in that water they would be energetically flying around and I would try to get them. You can't hold them, they are wiggling and they are very slippery. They eventually disappeared and then the frogs came. I never realized that the glass beads were jelly sacks of eggs or understood the three stages of frogs until I went to college and learned biology. Once I had all this knowledge about the miracle of science I came home from college to discover that the creek had dried up and my homeland was suffering much environmental damage. –Grist Magazine 15 Feb 2005 Wangari Maathai was born in Nyeri, Kenya in 1940 to farmers in the highlands of Mount Kenya.