Game and Fish Performance Audit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rep. John Kavanagh (Vice-Chair) Rep

House Committees Appropriations Education Rep. Regina Cobb (Chair) Rep. Michelle Udall (Chair) Rep. John Kavanagh (Vice-Chair) Rep. Bevely Pingerelli (Vice-Chair) Rep. César Chávez Rep. Daniel Hernandez Rep. Charlene Fernandez Rep. Joel John Rep. Randy Friese Rep. Quang Nguyen Rep. Jake Hoffman Rep. Jennifer Pawlik Rep. Steve Kaiser Rep. Frank Pratt Rep. Aaron Lieberman Rep. Bret Roberts Rep. Quang Nguyen Rep. Athena Salman Rep. Becky Nutt Rep. Judy Schweibert Rep. Joanne Osborne Rep. Judy Schwiebert Ethics Rep. Michelle Udall Rep. Becky Nutt (Chair) Rep. Frank Pratt (Vice-Chair) Commerce Rep. Domingo DeGrazia Rep. Jeff Weninger (Chair) Rep. Alma Hernandez Rep. Steve Kaiser (Vice-Chair) Rep. Jacqueline Parker Rep. Joseph Chaplik Rep. David Cook Government & Elections Rep. Diego Espinoza Rep. John Kavanagh (Chair) Rep. Charlene Fernandez Rep. Jake Hoffman (Vice-Chair) Rep. Robert Meza Rep. Judy Burges Rep. Becky Nutt Rep. Kelli Butler Rep. Pamela Powers Hannley Rep. Frank Carroll Rep. Justin Wilmeth Rep. John Fillmore Rep. Jennifer Jermaine Criminal Justice Reform Rep. Jennifer Pawlik Rep. Walt Blackman (Chair) Rep. Kevin Payne Rep. Shawnna Bolick (Vice-Chair) Rep. Athena Salman Rep. Reginald Bolding Rep. Stephanie Stahl Hamilton Rep. Alma Hernandez Rep. Raquel Terán Rep. Joel John Rep. Jeff Weninger Rep. Bret Roberts Rep. Diego Rodriguez Health & Human Services Rep. Raquel Terán Rep. Joanne Osborne (Chair) Rep. Ben Toma Rep. Regina Cobb (Vice-Chair) Rep. Kelli Butler Rep. Joseph Chaplik Rep. Randy Friese Rep. Alma Hernandez Rep. Jacqueline Parker Rep. Amish Shah Rep. Justin Wilmeth Judiciary Natural Resources, Energy & Water Rep. Frank Pratt (Chair) Rep. Gail Griffin (Chair) Rep. Jacqueline Parker (Vice-Chair) Rep. -

State of Arizona June 30, 2017 Single Audit Report

State of Arizona Single Audit Report Year Ended June 30, 2017 A Report to the Arizona Legislature The Arizona Office of the Auditor General’s mission is to provide independent and impartial information and specific recommendations to improve the operations of state and local government entities. To this end, the Office provides financial audits and accounting services to the State and political subdivisions, investigates possible misuse of public monies, and conducts performance audits and special reviews of school districts, state agencies, and the programs they administer. The Joint Legislative Audit Committee Representative Anthony Kern, Chair Senator Bob Worsley, Vice Chair Representative John Allen Senator Sean Bowie Representative Rusty Bowers Senator Judy Burges Representative Rebecca Rios Senator Lupe Contreras Representative Athena Salman Senator John Kavanagh Representative J.D. Mesnard (ex officio) Senator Steve Yarbrough (ex officio) Audit Staff Jay Zsorey, Director Nicole Franjevic, Manager and Contact Person Contact Information Arizona Office of the Auditor General 2910 N. 44th St. Ste. 410 Phoenix, AZ 85018 (602) 553-0333 www.azauditor.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Auditors Section Independent auditors’ report on internal control over financial reporting and on compliance and other matters based on an audit of basic financial statements performed in accordance with Government Auditing Standards 1 Independent auditors’ report on compliance for each major federal program; report on internal control over compliance; and report on schedule -

Champions, Friends and Foes

CHAMPIONS, FRIENDS AND FOES Senators Representatives Office Sought Office Sought Office Sought Sylvia Allen in 2018 John Allen in 2018 Travis Grantham in 2018 LD 6 Re-election LD 15 Re-election LD 12 Re-election Republican Republican Republican Nancy Barto Lela Alston Daniel Hernandez State State LD 15 LD 24 LD 2 Re-election House Senate Republican Democrat Democrat Sonny Borrelli Richard Andrade Drew John State LD 5 Re-election LD 29 Re-election LD 14 Senate Republican Democrat Republican Sean Bowie Brenda Barton Anthony Kern LD 18 Re-election LD 6 N/A LD 20 Re-election Democrat Republican Republican David Bradley Wenona Benally Jay Lawrence LD 10 Re-election LD 7 N/A LD 23 Re-election Democrat Democrat Republican Kate Brophy Isela Blanc Vince Leach McGee State Re-election LD 26 Re-election LD 11 LD 28 Senate Democrat Republican Republican Judy Burges Reginald Bolding David Livingston State LD 22 N/A LD 27 Re-election LD 22 Senate Republican Democrat Republican Olivia Cajero Russell Bowers Ray Martinez Bedford State LD 25 Re-election LD 30 N/A LD 3 House Republican Democrat Democrat Paul Boyer Lupe Contreras J.D. Mesnard LD 20 State State LD 19 Re-election LD 17 Republican Senate Senate Democrat Republican Andrea Kelli Butler Darin Mitchell Dalessandro Re-election LD 28 Re-election LD 13 Re-election LD 2 Democrat Republican Democrat Karen Fann Noel Campbell Paul Mosley LD 1 Re-election LD 1 Re-election LD 5 Re-election Republican Republican Republican Steve Farley Mark Cardenas Tony Navarrete State LD 9 Governor LD 19 N/A LD 30 Senate -

CSA Weekly Update November 23, 2016

CSA Weekly Update November 23, 2016 A research and advocacy association, supporting efficient, responsive county government in Arizona. In the November 23, 2016, CSA Weekly Update: • Happy Thanksgiving! • House & Senate Committee Membership Announced • VIDEO: 2016 CSA Summit Recap • This Week in Arizona History… • Interim Committee Agendas • NACo Webinar • Calendar Wishing Everyone a Happy Thanksgiving! Top House & Senate Committee Membership Announced This week the new Senate President Steve Yarbrough and new House Speaker J.D. Mesnard, both announced the majority membership and leadership of the legislative committees for the 2017 session. Please note both Senate Minority Leader Katie Hobbs and the House Minority Leader Rebecca Rios, are expected to announce the minority membership for the committees in the coming weeks. Please see below for committee detail. Senate Committees Appropriations Health and Human Services Sen. Debbie Lesko – Chair Sen. Nancy Barto – Chair Sen. John Kavanagh – Vice Chair Sen. Kate Brophy McGee – Vice Chair Sen. Sylvia Allen Sen. Debbie Lesko Sen. Steve Montenegro Sen. Steve Montenegro Sen. Warren Petersen Sen. Kimberly Yee Sen. Steve Smith Commerce and Public Safety Judiciary Sen. Steve Smith – Chair Sen. Judy Burges – Chair Sen. Warren Petersen – Vice Chair Sen. Nancy Barto – Vice Chair Sen. Sonny Borrelli Sen. Frank Pratt Sen. David Farnsworth Sen. Bob Worsley Sen. Bob Worsley Education Natural Resources, Energy and Water Sen. Sylvia Allen – Chair Sen. Gail Griffin – Chair Sen. Steve Montenegro – Vice Chair Sen. Frank Pratt – Vice Chair Sen. Kate Brophy McGee Sen. Sylvia Allen Sen. Steve Smith Sen. Judy Burges Sen. Kimberly Yee Sen. Karen Fann Finance Rules Sen. David Farnsworth – Chair President Steve Yarbrough – Chair Sen. -

2015 Legislative Report and Scorecard

2015 LEGISLATIVE REPORT AND SCORECARD Desert Nesting Bald Eagle photo by Robin Silver ARIZONA 2015 LEGISLATIVE REPORT By Karen Michael This year Humane Voters of Arizona (HVA) joined with other animal protection groups to form the Humane Legislative Coalition of Arizona (HCLA), an alliance of local animal advocacy organizations. Member groups include HVA, Animal Defense League of Arizona, Arizona Humane Society, and Humane Society of Southern Arizona. The coalition hired Brian Tassinari, the outstanding political consultant who helped to kill last session’s bad farm animal bill. This represents the Arizona animal community’s largest effort to date to protect our state’s animals and citizen initiative rights. Polls indicate that Arizona voters strongly support endangered Mexican wolf reintroduction and farm animal protection. This was demonstrated by the outpouring of support requesting a veto of the farm animal bill. Animal protection is a nonpartisan issue. A perfect example is that two of the most vocal supporters, Senators Farley and Kavanagh, are at polar ends of the political spectrum, yet they consistently agree when it comes to fighting for animals. The Good Bills The Cat Impound Exemption Bill (SB 1260) This beneficial measure exempts impounded cats from minimum holding periods at animal control facilities if the cat is eligible for a trap, neuter, return (TNR) program. Eligible cats are sterilized and ear-tipped and returned to their outdoor homes. Best Friends Animal Society drafted the original bill, SB 1198, which was sponsored by Senator Kavanagh. The bill failed on the House floor after an amendment was added to prohibit pound fees to be charged to anyone reclaiming an impounded cat. -

Arizona 2018 General Election Publicity Pamphlet

ARIZONA 2018 GENERAL ELECTION PUBLICITY PAMPHLET NOVEMBER 6, 2018 NOVEMBER 6, 2018 GENERAL ELECTION TABLE OF Contents General Voting Information A Message to Voters from Secretary of State Michele Reagan .................................................................................. 4 Voter Registration Information .................................................................................................................................. 5 Online Voter Services ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Vote by Mail and In Person Early Voting ................................................................................................................... 6 Military and Overseas Voters ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Voter Accessibility ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Alternative Pamphlet Formats.................................................................................................................................... 7 Polling Place/Vote Center Information ...................................................................................................................... 8 ID at the Polls – Bring It! ........................................................................................................................................ -

Final Vote SB 1318 2015 Legislative Session Arizona House Of

Final Vote SB 1318 2015 Legislative Session Arizona House of Representatives Y=33; N=24; NV=3 Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Legislator Vote Rep. Chris Ackerley N Rep. John Allen Y Rep. Lela Alston N Rep. Macario Saldate N Rep. Richard Andrade N Rep. Brenda Barton Y Rep. Jennifer Benally N Rep. Victoria Steele N Rep. Reginald Bolding N Rep. Sonny Borrelli Y Rep. Russell Bowers Y Rep. Kelly Townsend Y Rep. Paul Boyer Y Rep. Kate Brophy McGee Y Rep. Noel Campbell Y Rep. Jeff Wagner Y Rep. Mark Cardenas N Rep. Heather Carter NV Rep. Ken Clark N Rep. Andrew Sherwood N Rep. Regina Cobb Y Rep. Doug Coleman Y Rep. Diego Espinoza N Rep. David Stevens Y Rep. Karen Fann Y Rep. Edwin Farnsworth Y Rep. Charlene Fernandez N Rep. Michelle Ugenti Y Rep. Mark Finchem Y Rep. Randall Friese N Rep. Rosanna Gabaldon N Rep. Bruce Wheeler N Rep. Sally Ann Gonzales N Rep. Rick Gray Y Rep. Albert Hale N Rep. TJ Shope Y Rep. Anthony Kern Y Rep. Jonathan Larkin NV Rep. Jay Lawrence Y Rep. Bob Thorpe Y Rep. Vincent Leach Y Rep. David Livingston Y Rep. Phil Lovas Y Rep. Ceci Velasquez N Rep. Stefanie Mach N Rep. Debbie McCune Davis N Rep. Juan Mendez N Rep. David Gowen Y Rep. JD Mesnard Y Rep. Eric Meyer NV Rep. Darin Mitchell Y Rep. Rebecca Rios N Rep. Steve Montenegro Y Rep. Jill Norgaard Y Rep. Justin Olson Y Rep. Tony Rivero Y Rep. Lisa Otondo N Rep. Warren Peterson Y Rep. -

Arizona State Senate Committee Chairs 2021 Committee on Appropriations Sen. David Gowan-Chair Sen. Vince Leach-Vice Chair Commit

Arizona State Senate Committee Chairs 2021 Committee on Appropriations Sen. David Gowan-Chair Sen. Vince Leach-Vice Chair Committee on Commerce Sen. J.D. Mesnard-Chair Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita-Vice Chair Committee on Education Sen. Paul Boyer-Chair Sen. T.J. Shope-Vice Chair Committee on Finance Sen. David Livingston-Chair Sen. Vince Leach-Vice Chair Committee on Government Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita-Chair Sen. Kelly Townsend-Vice Chair Committee on Health & Human Services Sen. Nancy Barto-Chair Sen. Tyler Pace-Vice Chair Committee on Judiciary Sen. Warren Petersen-Chair Sen. Wendy Rogers-Vice Chair Committee on Natural Resources, Energy & Water Sen. Sine Kerr-Chair Sen. T.J. Shope-Vice Chair Committee on Transportation Sen. Tyler Pace-Chair Sen. T.J. Shope-Vice Chair Arizona State House Committee Chairs for 2021 Appropriations Rep. Regina Cobb (Chair) Rep. John Kavanagh (Vice Chair) Commerce Rep. Jeff Weninger (Chair) Rep. Steve Kaiser (Vice Chair) Criminal Justice Reform Rep. Walt Blackman (Chair) Rep. Shawnna Bolick (Vice Chair) Education Rep. Michelle Udall (Chair) Rep. Beverly Pingerelli (Vice Chair) Government & Elections Rep. John Kavanagh (Chair) Rep. Jake Hoffman (Vice Chair) Health & Human Services Rep. Joanne Osborne (Chair) Rep. Regina Cobb (Vice Chair) Judiciary Rep. Frank Pratt (Chair) Rep. Jacqueline Parker (Vice Chair) Land, Agriculture & Rural Affairs Rep. Tim Dunn (Chair) Rep. Joel John (Vice Chair) Military Affairs & Public Safety Rep. Kevin Payne (Chair) Rep. Quang Nguyen (Vice Chair) Natural Resources, Energy & Water Rep. Gail Griffin (Chair) Rep. Judy Burges (Vice Chair) Rules Rep. Becky Nutt (Chair) Rep. Travis Grantham (Vice Chair) Transportation Rep. Frank Carroll (Chair) Rep. -

Municipal 2012

2012 Municipal policy Statement Core Principles • PROTECTION OF SHARED REVENUES. Arizona’s municipalities rely on the existing state-collected shared revenue system to provide quality services to their residents. The League will resist any attacks on this critical source of funding for localities, which are responsibly managing lean budgets during difficult economic times. The League opposes unfunded legislative mandates, as well as the imposition of fees and assessments on municipalities as a means of shifting the costs of State operations onto cities and towns. In particular, the League opposes any further diversions of Highway User Revenue Fund (HURF) monies away from municipalities and calls upon the Legislature to restore diverted HURF funding to critical road and street projects. • PRESERVATION OF LOCAL CONTROL. The League calls upon the Arizona Legislature to respect the authority of cities and towns to govern their communities free from legislative interference and the imposi- tion of regulatory burdens. The League shares the sentiments of Governor Brewer, who, in vetoing anti-city legislation last session, wrote: “I am becoming increasingly concerned that many bills introduced this session micromanage decisions best made at the local level. What happened to the conservative belief that the most effective, responsible and responsive government is government closest to the people?” Fiscal Stewardship The League is prepared to support reasonable reforms to the state revenue system that adhere to the principles of simplicity, fairness and balance and that do not infringe upon the ability of cities and towns to implement tax systems that reflect local priorities and economies. • The League proposes to work with the Legislature to ensure that both the State and municipalities are equipped with the economic development tools they need to help them remain competitive nationally and internationally. -

Download 2014 Summaries As a High Resolution

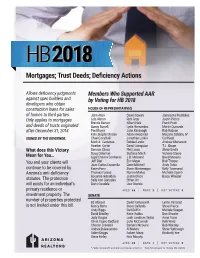

HB2018 Mortgages; Trust Deeds; Deficiency Actions Allows deficiency judgments Members Who Supported AAR against spec builders and by Voting for HB 2018 developers who obtain HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES construction loans for sales of homes to third parties. John Allen David Gowan Jamescita Peshlakai Only applies to mortgages Lela Alston Rick Gray Justin Pierce Brenda Barton Albert Hale Frank Pratt and deeds of trusts originated Sonny Borrelli Lydia Hernandez Martin Quezada after December 31, 2014. Paul Boyer John Kavanagh Bob Robson Kate Brophy McGee Adam Kwasman Macario Saldate, IV SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Mark A. Cardenas Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood Heather Carter David Livingston T.J. Shope What does this Victory Demion Clinco Phil Lovas Steve Smith Doug Coleman Stefanie Mach Victoria Steele Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras J.D. Mesnard David Stevens You and your clients will Jeff Dial Eric Meyer Bob Thorpe Juan Carlos Escamilla Darin Mitchell Andy Tobin continue to be covered by Karen Fann Steve Montenegro Kelly Townsend Arizona’s anti-deficiency Thomas Forese Norma Muñoz Michelle Ugenti Rosanna Gabaldón Justin Olson Bruce Wheeler statutes. The protection Sally Ann Gonzales Ethan Orr will exists for an individual’s Doris Goodale Lisa Otondo primary residence or AYES: 55 | NAYS: 2 | NOT VOTING: 3 investment property. The SENATE number of properties protected Ed Ableser David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi is not limited under this bill. Nancy Barto Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee Steve Farley Rick Murphy AYES: 29 | NAYS: 1 | NOT VOTING: 0 * Eddie Farnsworth and Warren Petersen voted no – they did not want to change the statute. -

Sunset Review of the Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board

Sunset Review of the Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board Report December 2017 SENATE MEMBERS HOUSE MEMBERS Senator Gail Griffin, Co-Chair Representative Brenda Barton, Co-Chair Senator Sylvia Allen Representative David L. Cook Senator Judy Burges Representative Eric Descheenie Senator Andrea Dalessandro Representative Kirsten Engel Senator Lisa Otondo Representative Michelle Udall TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Report A. Background B. Committee of Reference Sunset Review Procedures C. Committee Recommendations II. Appendix A. Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board's Response to the Sunset Factors B. Meeting Notice C. Minutes of the Committee of Reference Meeting D. Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board's PowerPoint Presentation Background Pursuant to A.R.S. § 41-2953, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee assigned the sunset review of the Arizona State Veterinary Medical Examining Board (Board) to the Senate Natural Resources, Energy and Water and the House of Representatives Energy, Environment and Natural Resources Committee of Reference (COR). The Board was established by Laws 1967, Chapter 76. The Board is comprised of five licensed veterinarians, one certified veterinary technician, two non-veterinarian members representing the general public and one non-veterinarian member representing the livestock industry (A.R.S. § 32-2202). All members are appointed by the Governor, confirmed by the Senate, and may serve up to two four-year terms. The Board's primary duty is to "protect the public from unlawful, incompetent, unqualified, impaired or unprofessional practitioners of veterinary medicine through licensure and regulation of the profession in this State" (A.R.S. § 32-2207). The Board licenses veterinarians, veterinary medical premises and animal crematories, and certifies veterinary technicians. -

Download 2016 Summaries As a High Resolution

SB1350 Online Lodging; Administration; Members Who Supported AAR by Voting for SB 1350 Definition House of Representatives J. Christopher Ackerley Randall Friese Justin Olson Establishes regulations for online John M. Allen Rosanna Gabaldón Lisa A. Otondo lodging, vacation and short-term Lela Alston Sally Ann Gonzales Warren H. Petersen rental operations. Also requires Richard C. Andrade Rick Gray Celeste Plumlee the Arizona Department of Brenda Barton Albert Hale Franklin M. Pratt Jennifer D. Benally Matthew A. Kopec Rebecca Rios Revenue to develop an electronic, Reginald Bolding Jr. Jonathan R. Larkin Bob Robson consolidated return form for Sonny Borrelli Jay Lawrence Macario Saldate use by property managers filing Paul Boyer Vince Leach Thomas “T.J.” Shope Transaction Privilege Tax on Kate Brophy McGee David Livingston David W. Stevens Mark A. Cardenas Stefanie Mach Bob Thorpe behalf of their clients. Heather Carter Debbie McCune Davis Kelly Townsend SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Ken Clark Juan Jose Mendez Ceci Velasquez Regina Cobb Javan D. “J.D.” Mesnard Jeff Weninger Doug Coleman Eric Meyer Bruce Wheeler What This Victory Means Karen Fann Darin Mitchell David M. Gowan Sr. for You… Eddie Farnsworth Steve Montenegro Enables the homeowner to Charlene R. Fernandez Jill Norgaard exercise their private property 52 Ayes │ 6 Nays │ 2 Not Voting rights and streamlines the Senate ® REALTOR ’S ability to file Sylvia Allen Gail Griffin Andrew C. Sherwood Transaction Privilege Taxes on Carlyle Begay Katie Hobbs Don Shooter behalf of their client. David Bradley Debbie Lesko Steve Smith Judy Burges Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Lupe Contreras Robert Meza Steve Yarbrough Andrea Dalessandro Catherine Miranda Kimberly Yee Jeff Dial Lynne Pancrazi Andy Biggs Adam Driggs Steve Pierce Steve Farley Martin Quezada 25 Ayes │ 3 Nays │ 2 Not Voting SB1402 Class Six Property; Higher Education Members Who Supported AAR by Voting AGAINST SB 1402 Would have allowed for-profit House of Representatives institutions of higher education Lela Alston Mark Finchem Lisa A.