The Mentor 90

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

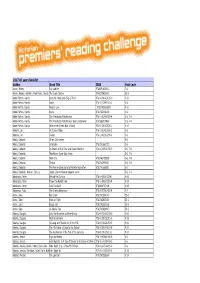

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

YOUNG WRITERS ONLINE Senior Writers Sessions with Isobelle Carmody Released Term 2, 2020

YOUNG WRITERS ONLINE Senior Writers Sessions with Isobelle Carmody Released Term 2, 2020 What is included? 9 x Creative Writing Sessions – Descriptions Updated 12 June Session 1 – Drawing on Life (29 minutes) Isobelle introduces herself and gives a reading from The Monster Game, from Green Monkey Dreams. This session focuses on drawing on your own life to create believable scenarios and characters with writing exercises focussing on emotions. Session 2 – Using Fairy Tales (22 minutes) In this session Isobelle will read from Moth’s Tale, one of her short stories in The Wilful Eye, and give insights into its background. She focuses on using fairy tales with practical writing exercises to support the reading. Session 3 – World Building (18 minutes) Isobelle gives the background to the creation of her legendary series, The Obernewtyn Chronicles. She focuses on how to build an imaginary history as the back drop to your story. This is her guide to world building – the do’s and don’ts. Session 4 – Building Atmosphere (22 minutes) Following a reading from one of her most famous books, The Gathering, Isobelle discusses its creation and development. Then focuses on how to build atmosphere in your narrative and will lead you in some impressionist writing exercises. Session 5 – Graphic Novels & Using Your Beliefs (19 minutes) In this session, Isobelle will read from her graphic post-apocalyptic fairy tale, Evermore, which is currently being adapted as a mini-series. She also discusses her collaboration with its illustrator, Dan Reed. In this session students will write about their and their characters’ beliefs. -

FINAL 2017 Year 9-10 Booklist.Xlsx

2017 Years 9-10 Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Adams, Douglas Life, the Universe and Everything 978-0-330-26738-0 9-10 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless 978-0-330-32311-6 9-10 Adams, Douglas So Long and Thanks for All the Fish 978-0-330-28700-5 9-10 Adams, Douglas The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy 978-0-330-49119-8 9-10 Adams, Douglas The Restaurant at the End of the Universe 978-0-330-26213-2 9-10 Adams, Jessica; Partridge, Juliet; Earls, NickKid's Night In! 978-0-14-330058-8 9-10 Adams, Michael The Last Girl 9781743316368 9-10 Adams, Michael The Last Place 9781743316740. 9-10 Adams, Michael The Last Shot 9781743316733 9-10 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades 9780312656270 9-10 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo 9780312656263 9-10 Adornetto, Alexandra Heaven 9780312656287 9-10 Albertalli, Becky Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda 9780062348678 9-10 Albom, Mitch Tuesdays with Morrie 9780733622694 9-10 Alcott, Louisa May Eight Cousins 978-0-14-037456-8 9-10 Alcott, Louisa May Good Wives 978-0-14-036695-2 9-10 Alcott, Louisa May Jo's Boys 978-0-14-036714-0 9-10 Alcott, Louisa May Little Men 978-0-14-036713-3 9-10 Alcott, Louisa May Little Women 978-1-904633-27-3 9-10 Alexander, Goldie Hanna My Holocaust Story 9781743629673 7-8, 9-10 Alexie, Sherman The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian 978-1-84270-844-6 9-10 Allen, Judy The Blue Death 978-0-340-80571-8 9-10 Almond, David My Name Is Mina 978-0-340-99725-3 7-8, 9-10 Almond, David Skellig 978-0-340-71600-7 7-8, 9-10 Anderson, Laurie Halse Fever 1793 978-0-340-85409-9 9-10 Anderson, M. -

Green Monkey Dreams Free Download

GREEN MONKEY DREAMS FREE DOWNLOAD Isobelle Carmody | 324 pages | 01 Jun 2013 | Allen & Unwin | 9781742379470 | English | Sydney, Australia Dreams About Monkeys – Interpretation and Meaning I think I took so Green Monkey Dreams more out of these stories now Green Monkey Dreams a 25 year old compared to when 21 year old me, who was only really starting to experience the real word. Jan 26, Betty rated it liked it Shelves: young-adult-fiction. You might be acting childish in some situations. Maddy rated it really liked it May 18, I liked how Carmody showed how hopeful a new start can be. Archived from the original on 17 October Young Adult. Back to top. The reason hfor his defeat is the fact that Allah has deprived him of His favours because of his sins, infamy and wickedness. Only people wanting to join Green Monkey Dreams city were allowed inside. Showing Abstract History Archive Description. Despite the fact that such conditions were inevitably destructive, and more often than not produced psychologically flawed adults, this custom of families continued right up to the wars. I loved the way that some of the stories ma - Update March Green Monkey Dreams On reread I am bumping this up to 5 stars. This dream might also indicate the need to remove some negative things and people out of your life. Alyscia Marston rated it really liked it Jun 11, My fav genre too! There were no healers in Glory. If you dreamed about having a monkey as a pet, such a dream might be a sign of your fears overwhelming you. -

Green Monkey Dreams Ebook Free Download

GREEN MONKEY DREAMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Isobelle Carmody | 324 pages | 01 Jun 2013 | Allen & Unwin | 9781742379470 | English | Sydney, Australia Green Monkey Dreams PDF Book Image courtesy of Penguin Books. Most of these stories were either set in a different world, or had magical aspects within the stories. The Sending , book six of that series, was officially released on 31 October Dreaming about being afraid of a monkey. If yellowish, it means worries and sorrow. Works by Isobelle Carmody. I think this collection is probably classed as YA but I think it is suitable for adults too, who might find more meaning buried into the stories. Publisher: Viking. The last thing I could remember clearly was running along the main street in Glory. It is also said that wearing a green garment in a dream means receiving an inheritance. Isobelle Carmody writes well- but fantasy is just not my genre, and short stories often leave me unsatisfied. Also published as Night Gate [9]. It isn't a genre that I tend to enjoy, but if you're going to read fantasy Carmody is a good choice Lists with This Book. Redirected from Green Monkey Dreams collection. Community Reviews. Such a person disrupts his life through his own actions and sins and is despised in people's eyes. Beneath the smiles and kind gestures lurks a darkness that is capable of c The High Path is a road of sorrow. I will soon be rereading this book because it will This is a difficult book to review as the worlds of the tales range from an apocalyptic world to what could be right next door. -

Best Science Fiction Novel

aurealis awards, previous years’ results best science fiction novel year award designation author title series publisher 1995 winner Greg Egan Distress Millennium Sean McMullen Mirrorsun Rising Greatwinter #1.5 Aphelion finalists Kate Orman Set Piece Doctor Who New Adventures #35 Virgin Sean Williams & Shane Dix The Unknown Soldier The Cogal #1 Aphelion 1996 winner Sean Williams Metal Fatigue HarperCollins Australia Simon Brown Privateer HarperCollins finalists Tess Williams Map of Power Random/Arrow 1997 winner Damien Broderick The White Abacus Avon Eos Damien Broderick & Rory Barnes Zones HarperCollins Australia/Moonstone Simon Brown Winter HarperCollins Australia finalists Greg Egan Diaspora Millennium Richard Harland The Dark Edge The Eddon + Vail #1 Pan Macmillan 1998 winner Sean McMullen The Centurion’s Empire Tor Alison Goodman Singing the Dogstar Blues HarperCollins John Marsden The Night Is for Hunting Tomorrow #6 Pan Macmillan finalists Kate Orman The New Adventures: Walking to Babylon Doctor Who – Bernice Virgin Summerfield #10 Sean Williams The Resurrected Man HarperCollins 1999 winner Greg Egan Teranesia Victor Gollancz Rory Barnes & Damien Broderick The Book of Revelation HarperCollins/Voyager Andrew Masterson The Letter Girl Picador finalists Jonathan Blum & Kate Orman Doctor Who: Unnatural History Eigth Doctor Adventures #23 BBC Books Sally Rogers-Davidson Spare Parts Penguin Books 2000 winner Sean McMullen The Miocene Arrow Greatwinter #2 Tor James Bradley The Deep Field Sceptre finalists Sean Williams & Shane Dix The -

Booklist All Years.Xlsx

2019 All Years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.) The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker series 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa When Michael Met Mina 9781743534977 7-8, 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Stupendously Spectacular Spelling Bee 9781925324822 3-4, 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 -

Premiers Reading Challenge

01/06/2021 All levels Everything All categories Page 1 ID Title Author Call number Level Matches 12 Franklin wants a badge EC-2 13834 The ABC book of lullabies EC-2 13835 The ABC book of nursery rhymes EC-2 13838 The Walker book of bear stories EC-2 13840 A monster in my house EC-2 14562 The little book of Possum magic EC-2 2 George speaks EC-2 37 Treasury of nursery rhymes EC-2 47 Our island EC-2 48 Lavender's blue: a book of nursery EC-2 rhymes 50 Warnayarra, the Rainbow Snake EC-2 55 The Big book of little poems EC-2 56 Kenju's forest EC-2 6 Where is Nana? EC-2 63 Poems for the very young EC-2 77 The duck catcher Aaron, Moses EC-2 78 Buzz off! Abdel-Fattah, Randa EC-2 107 As big as you Acton, Sara EC-2 108 Ben & duck Acton, Sara EC-2 109 Hold on tight Acton, Sara EC-2 110 Poppy cat Acton, Sara EC-2 138 Chicken, chips and peas Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 139 Everybody was a baby once: and Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 other poems 140 Grandma Fox Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 141 Miss Dose the doctors' daughter Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 144 The adventures of Bert Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 147 The runaway dinner Ahlberg, Allan EC-2 14604 Each peach pear plum Ahlberg, Janet EC-2 148 Jeremiah in the Dark Woods Ahlberg, Janet EC-2 158 Bao bao Alborough, Jez EC-2 159 Cuddly Dudley Alborough, Jez EC-2 160 Fix-it Duck: and other stories Alborough, Jez EC-2 161 Hug Alborough, Jez EC-2 162 Hugo the Hare's rainy day Alborough, Jez EC-2 163 My friend bear Alborough, Jez EC-2 164 Some dogs do Alborough, Jez EC-2 165 Super Duck Alborough, Jez EC-2 166 Watch out! Big bro's coming! Alborough, -

Best Science Fiction Novel

best science fiction novel year award designation author title series publisher winner Greg Egan Distress Millennium Sean McMullen Mirrorsun Rising Greatwinter #1.5 Aphelion 1995 Set Piece Doctor Who New finalists Kate Orman Adventures #35 Virgin Sean Williams & The Unknown Soldier Shane Dix The Cogal #1 Aphelion winner Sean Williams Metal Fatigue HarperCollins Australia 1996 Simon Brown Privateer HarperCollins finalists Tess Williams Map of Power Random/Arrow winner Damien Broderick The White Abacus Avon Eos Damien Broderick & Zones HarperCollins Rory Barnes Australia/Moonstone 1997 finalists Simon Brown Winter HarperCollins Australia Greg Egan Diaspora Millennium The Dark Edge The Eddon + Vail Richard Harland #1 Pan Macmillan winner Sean McMullen The Centurion’s Empire Tor Alison Goodman Singing the Dogstar Blues HarperCollins John Marsden The Night Is for Hunting Tomorrow #6 Pan Macmillan 1998 finalists The New Adventures: Walking to Doctor Who – Kate Orman Babylon Bernice Virgin Summerfield #10 Sean Williams The Resurrected Man HarperCollins winner Greg Egan Teranesia Victor Gollancz Rory Barnes & The Book of Revelation Damien Broderick HarperCollins/Voyager 1999 Andrew Masterson The Letter Girl Picador finalists Jonathan Blum & Doctor Who: Unnatural History Eigth Doctor Kate Orman Adventures #23 BBC Books Sally Rogers- Spare Parts Davidson Penguin Books winner Sean McMullen The Miocene Arrow Greatwinter #2 Tor 2000 finalists James Bradley The Deep Field Sceptre Sean Williams & The Dying Light Shane Dix Evergence #2 HarperCollins/Voyager -

All Year Levels Booklist Author Title Year Levels

All Year Levels Booklist Author Title Year Levels Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.) The Duck Catcher EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker series 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 5-6 Abela, Deborah A Transylvanian Tale 5-6 Abela, Deborah Blue's Revenge 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Mission in Malta 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Spyforce Revealed 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Amazon Experiment 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Final Curtain 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The French Code 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Hollywood Mission 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Nightmare Vortex 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 5-6 Abela, Deborah The Venice Job 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny The Finals 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny The Game of Life 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny The Striker 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat EC-2 Adams, Douglas Life, the Universe and Everything 9-10 Adams, Douglas Mostly Harmless -

Best Science Fiction Novel

aurealis awards, previous years’ results best science fiction novel year award designation author title series publisher 1995 winner Greg Egan Distress Millennium Sean McMullen Mirrorsun Rising Greatwinter #1.5 Aphelion finalists Kate Orman Set Piece Doctor Who New Adventures #35 Virgin Sean Williams & Shane Dix The Unknown Soldier The Cogal #1 Aphelion 1996 winner Sean Williams Metal Fatigue HarperCollins Australia Simon Brown Privateer HarperCollins finalists Tess Williams Map of Power Random/Arrow 1997 winner Damien Broderick The White Abacus Avon Eos Damien Broderick & Rory Barnes Zones HarperCollins Australia/Moonstone Simon Brown Winter HarperCollins Australia finalists Greg Egan Diaspora Millennium Richard Harland The Dark Edge The Eddon + Vail #1 Pan Macmillan 1998 winner Sean McMullen The Centurion’s Empire Tor Alison Goodman Singing the Dogstar Blues HarperCollins John Marsden The Night Is for Hunting Tomorrow #6 Pan Macmillan finalists Kate Orman The New Adventures: Walking to Babylon Doctor Who – Bernice Virgin Summerfield #10 Sean Williams The Resurrected Man HarperCollins 1999 winner Greg Egan Teranesia Victor Gollancz Rory Barnes & Damien Broderick The Book of Revelation HarperCollins/Voyager Andrew Masterson The Letter Girl Picador finalists Jonathan Blum & Kate Orman Doctor Who: Unnatural History Eigth Doctor Adventures #23 BBC Books Sally Rogers-Davidson Spare Parts Penguin Books 2000 winner Sean McMullen The Miocene Arrow Greatwinter #2 Tor James Bradley The Deep Field Sceptre finalists Sean Williams & Shane Dix The