Joint Committee on the Draft Corruption Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission for Equality and Human Rights: the Government's White Paper

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Commission for Equality and Human Rights: The Government's White Paper Sixteenth Report of Session 2003–04 HL Paper 156 HC 998 House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Commission for Equality and Human Rights: The Government's White Paper Sixteenth Report of Session 2003–04 Report, together with formal minutes and appendices Ordered by The House of Lords to be printed 21 July 2004 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 21 July 2004 HL Paper 156 HC 998 Published on 4 August 2004 by authority of the House of Lords and the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current Membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness Mr David Chidgey MP (Liberal Democrat, Eastleigh) Lord Campbell of Alloway Jean Corston MP (Labour, Bristol East) (Chairman) Lord Judd Mr Kevin McNamara MP (Labour, Kingston upon Hull) Lord Lester of Herne Hill Mr Richard Shepherd MP Lord Plant of Highfield (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Baroness Prashar Mr Paul Stinchcombe (Labour, Wellingborough) Mr Shaun Woodward MP (Labour, St Helens South) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

September 2017 Issue

Hambledon Parish Magazine St Peter’s Church & Village News September 2017 60p www.hambledonsurrey.co.uk Hambledon Parish Magazine, September 2017 Page 1 Hambledon Parish Magazine, September 2017, Page 2 PARISH CHURCH OF ST PETER, HAMBLEDON Rector The Rev Simon Taylor 01483 421267 [email protected] Associate Vicar The Rev Catherine McBride 01483 421267 Mervil Bottom, Malthouse Lane, Hambledon GU8 4HG [email protected] Assistant Vicar The Rev David Jenkins 01483 416084 6 Quartermile Road Godalming GU7 1TG Curate The Rev David Preece 01483 421267 2 South Hill, Godalming, GU7 1JT [email protected] Churchwarden Mrs Elizabeth Cooke Marepond Farm, Markwick Lane Loxhill, Godalming, GU8 4BD 01483 208637 Churchwarden Alan Harvey 01483 423264 35 Maplehatch Close, Godalming, GU7 1TQ Assistant Churchwarden Mr David Chadwick, Little Beeches, 14 Springhill, Elstead, Godalming, GU8 6EL 01252 702268 Church Treasurer & Gift Aid Dr Alison Martin Tillies, Munstead Heath Road Godalming GU8 4AR 01483 893619 Sunday Services Full details of these and any other services are set out in the Church Calendar for the month, which is shown on page 5 The Church has a number of Home Groups which meet regularly during the week at various locations. Details from Catherine McBride Tel: 01483 421267 Alpha details and information from The Rev Catherine McBride Tel: 01483 421267 Baptisms, Weddings and Funerals contact Hambledon and Busbridge Church Office Tel No: 01483 421267 (Mon – Friday, 9.30am – 12.30pm) Where there is sickness or -

Section 19 of the Human Rights Act 1998 Importance, Impact and Reform

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Section 19 of the Human Rights Act 1998 importance, impact and reform Weston, Elin Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Title: Section 19 of the Human Rights Act 1998: importance, impact and reform Author: Elin Weston The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

Review of Past ACA Payments

House of Commons Members Estimate Committee Review of past ACA payments First Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 2 February 2010 HC 348 Published on 4 February 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £23.00 Members Estimate Committee The Members Estimate Committee has the same Members as the House of Commons Commission: Rt Hon John Bercow MP, Speaker Sir Stuart Bell MP Rt Hon Harriet Harman MP, Leader of the House Nick Harvey MP Rt Hon David Maclean MP Rt Hon Sir George Young MP, Shadow Leader of the House The Committee is appointed under Standing Order No 152D (House of Commons Members Estimate Committee): 152D.—(1) There shall be a committee of this House, called the House of Commons Members Estimate Committee. (2) The members of the committee shall be those Members who are at any time members of the House of Commons Commission pursuant to section 1 of the House of Commons (Administration) Act 1978; the Speaker shall be chairman of committee; and three shall be the quorum of the committee. (3) The functions of the committee shall be— (a) to codify and keep under review the provisions of the resolutions of this House and the Guide to Members’ Allowances known as the Green Book relating to expenditure charged to the Estimate for House of Commons: Members; (b) to modify those provisions from time to time as the committee may think necessary or desirable in the interests of clarity, consistency, accountability and effective administration, and conformity with current circumstances; (c) to provide advice, when requested by the Speaker, on the application of those provisions in individual cases; (d) to carry out the responsibilities conferred on the Speaker by the resolution of the House of 5th July 2001 relating to Members’ Allowances, Insurance, &c.; (e) to consider appeals against determinations made by the Committee on Members’ Allowances under paragraph (1)(d) of Standing Order No. -

Member Since 1979 191

RESEARCH PAPER 09/31 Members since 1979 20 APRIL 2009 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979, together with basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and the House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. Since this Paper is produced part way through the 2005 Parliament, a subsequent edition will be prepared after its dissolution to create a full record of its MPs. The cut off date for the material in this edition is 31 March 2009. Please note that a new edition of this Research Paper is now available entitled: Members 1979-2010 [RP10/33] Oonagh Gay PARLIAMENT AND CONSTITUTION CENTRE HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 09/16 Saving Gateway Accounts Bill: Committee Stage Report 24.02.09 09/17 Autism Bill [Bill 10 of 2008-09] 25.02.09 09/18 Northern Ireland Bill [Bill 62 of 2008-09] 02.03.09 09/19 Small Business Rate Relief (Automatic Payment) Bill [Bill 13 of 03.03.09 2008-09] 09/20 Economic Indicators, March 2009 04.03.09 09/21 Statutory Redundancy Pay (Amendment) Bill [Bill 12 of 2008-09] 11.03.09 09/22 Industry and Exports (Financial Support) Bill [Bill 70 of 2008-09] 12.03.09 09/23 Welfare Reform Bill: Committee Stage Report 13.03.09 09/24 Royal Marriages and Succession to the Crown (Prevention of 17.03.09 Discrimination) Bill [Bill 29 of 2008-09] 09/25 Fuel Poverty Bill -

NOTICE of POLL Election of a County Councillor

NOTICE OF POLL Borough of Wellingborough Election of a County Councillor for Hatton Park Electoral Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Hatton Park Electoral Division will be held on Thursday 2 May 2013, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates’ nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors HORNETT 2 Roberts Street, Green Party D Prior (+) Kevan Prior (++) Emma Jane Wellingborough, P J John C W John NN8 3HY H Orton F Orton M Kavanagh D M Mann D H Mann M L Flawn JONES 3 Glebe Farm Court, Liberal Democrat F J Ratcliffe (+) W J J Ratcliffe (++) Norman Glyn Great Doddington, Reuben Leach Joanne Pusey Wellingborough, Jason Love Mel Love NN29 7TP B Bond D Hyman V L Button A P Hyman SHIPHAM 8 Yarrow Court, UK Independence P Martin (+) B Taylor (++) Allan James Wellingborough, Party T J Crowe C Nash Northants, NN8 3DX M Whitehead M D Hayes J Wilson D Ray P G Adams A J Clarke WALKER 38 Buckwell Close, English Democrats - D Smith (+) S Smith (++) Rob Wellingborough, "Putting England First!" C A Thomas S P Darwin Northamptonshire, F G Howell J Rawlings-Smith NN8 5BP D J Atkinson T L Gannon Paul Golley D Samson WATERS 7 Torrington Green, Conservative Party B R Patel (+) P Raymond (++) Malcolm Wellingborough, John A Raymond L Wilson NN8 5BT S D Mead L G Prestage C Cadby R Cadby Simon Barnes L A Newman WATTS 86 Ridgeway, The Labour Party Paul Stinchcombe (+) Catherine Mulholland Andrea Jayne Wellingborough, Candidate Graham K Sherwood (++) Northants, NN8 4RY Neville T Marsden Geoffrey C Taylor James T Ashton G M Marsden S Watts Anne M Ashton E Howard 4. -

The Future of Social Justice in Britain: a New Mission for the Community Legal Service

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online The Future of Social Justice in Britain: A New Mission for the Community Legal Service Jonathan M. Stein Contents 1. Introduction – A Community Legal Service Bereft of a Social Justice Mission ... 1 2. A Strategy to Produce Larger Civil Justice Impacts with Limited Resources.... 11 Limits of individual casework................................................................................... 12 Impacting on poverty and exclusion........................................................................ 14 Impacting on employment, ethnic minorities, and community renewal issues ........................................................................................................................ 20 Reforming the legal aid legacy.................................................................................. 22 3. Delivering a Social Justice Mission Through Not-for-Profit Providers – Neighbourhood Law Centres and Independent Advice Agencies................. 25 4. Establishing a Broad Right to Civil Legal Aid Under the Human Rights Act ... 34 5. Summary Recommendations and Conclusion........................................................ 41 CASEpaper 48 Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion August 2001 London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE CASE enquiries – tel: 020 7955 6679 Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion The ESRC Research Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) was established in October 1997 with funding from -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT Whose party? Whose interests? Childcare policy, electoral imperative and organisational reform within the US Democrats, Australian Labor Party and Britain’s New Labour KATHLEEN A. HENEHAN A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LONDON AUGUST 2014 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 91,853 words. 2 ABSTRACT The US Democrats, Australian Labor Party and British Labour Party adopted the issue of childcare assistance for middle-income families as both a campaign and as a legislative issue decades apart from one and other, despite similar rates of female employment. The varied timing of parties’ policy adoption is also uncorrelated with labour shortages, union density and female trade union membership. However, it is correlated with two politically-charged factors: first, each party adopted childcare policy as their rate of ‘organised female labour mobilisation’ (union density interacted with female trade union membership) reached its country-level peak; second, each party adopted the issue within the broader context of post-industrial electoral change, when shifts in both class and gender-based party-voter linkages dictated that the centre-left could no longer win elections by focusing largely on a male, blue-collar base. -

Land at Dunsfold Park, Stovolds Hill, Cranleigh, Surrey, Gu6 8Tb Application Ref: W/2015/2395

Our ref: APP/R3650/V/17/3171287 Peter Seaborn Your ref: M&R-FirmDMS.FID34838921 Mills & Reeve Botanic House, 100 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1PH 29 March 2018 Dear Sir TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 77 APPLICATION MADE BY DUNSFOLD AIRPORT LIMITED AND RUTLAND LIMITED LAND AT DUNSFOLD PARK, STOVOLDS HILL, CRANLEIGH, SURREY, GU6 8TB APPLICATION REF: W/2015/2395 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of Philip Major BA(Hons) DipTP MRTPI, who held a public local inquiry between 18 July and 3 August 2017 into your client’s application for planning permission for a hybrid planning application; part Outline proposal for a new settlement with residential development comprising 1,800 units (Use Class C3), plus 7,500sqm care accommodation (Use Class C2), a local centre to comprise retail, financial and professional, cafes / restaurant / takeaway and/or public house up to a total of 2,150sqm (Use Classes A1, A2, A3, A4, A5); new business uses including offices, and research and development industry (Use Class B1a and B1b) up to a maximum of 3,700sqm; storage and distribution (Use Class B8) up to a maximum of 11,000sqm; a further 9,966sqm of flexible commercial space (B1(b), B1(c), B2 and/or B8); non-residential institutions including health centre, relocation of the existing Jigsaw School into new premises and provision of new community centre (Use Class D1) up to a maximum of 9,750sqm; a two-form entry primary school; open space including water bodies, outdoor sports, recreational -

Read Publication

prelims.qxd 10/13/2003 18:57 Page 1 About Policy Exchange Policy Exchange is an independent think tank whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas which will foster a free society based on limited government, strong communities, personal freedom and national selfconfidence. Working in partnership with independent academics and experts, we commission original research into important issues of policy and use the findings to develop practical recom mendations for government. Policy Exchange seeks to learn lessons from the approaches adopted in other countries and to assess their relevance to the UK context. We aim to engage with people and groups across the political spectrum and not be restricted by outdated notions of left and right. Policy Exchange is a registered charity (no: 1096300) and is funded by individuals, grant making trusts and companies. Trustees Chairman of the Board: Michael Gove Adam Afriyie Colin Barrow Camilla Cavendish Iain Dale Robin Edwards John Micklethwait Alice Thompson Ian Watmore Rachel Whetstone prelims.qxd 10/13/2003 18:57 Page 2 . Charles Banner is a Research Fellow at Policy Exchange. He read Classics at Lincoln College, Oxford, and Law at City University. He has worked in management consultancy and contributed to two Policy Exchange publications about the police in 2002. He teaches constitu- tional law at City University and is a part-time volunteer adviser in European Union and human rights law at the AIRE Centre in London. He is due to start work as a pupil barrister at Landmark Chambers in October 2004. Alexander Deane is a Research Fellow at Policy Exchange. -

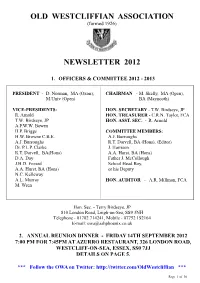

OWA Newsletter 2012 PDF File

OLD WESTCLIFFIAN ASSOCIATION (formed 1926) NEWSLETTER 2012 1. OFFICERS & COMMITTEE 2012 - 2013 PRESIDENT - D. Norman, MA (Oxon), CHAIRMAN - M. Skelly, MA (Open), M.Univ (Open) BA (Maynooth) VICE-PRESIDENTS: HON. SECRETARY - T.W. Birdseye, JP R. Arnold HON. TREASURER - C.R.N. Taylor, FCA T.W. Birdseye, JP HON. ASST. SEC. - R. Arnold A.P.W.W. Bowen H.P. Briggs COMMITTEE MEMBERS: H.W. Browne C.B.E. A.J. Burroughs A.J. Burroughs R.T. Darvell, BA (Hons), (Editor) Dr. P.L.P. Clarke J. Harrison R.T. Darvell, BA(Hons) A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) D.A. Day Father J. McCollough J.H.D. Fozard School Head Boy, A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) or his Deputy N.C. Kelleway A.L. Murray HON. AUDITOR - A.R. Millman, FCA M. Wren Hon. Sec. - Terry Birdseye, JP 810 London Road, Leigh-on-Sea, SS9 3NH Telephone - 01702 714241, Mobile - 07752 192164 E-mail: [email protected] 2. ANNUAL REUNION DINNER - FRIDAY 14TH SEPTEMBER 2012 7:00 PM FOR 7:45PM AT AZURRO RESTAURANT, 326 LONDON ROAD, WESTCLIFF-ON-SEA, ESSEX, SS0 7JJ DETAILS ON PAGE 5. *** Follow the OWA on Twitter: http://twitter.com/OldWestcliffian *** Page 1 of 36 Page 2 of 36 CONTENTS 1. Officers & Committee 2012 - 2013. 2. O.W.A Annual Reunion Dinner, Friday 14th September 2012 - 7:00 pm for 7:45 pm at Azurro Restaurant, 326 London Road, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, SS0 7JJ. Details and reply slips on page 5. 3. (i) Honorary Secretary - Careers Guidance Support Form (ii) New Members (iii) Donations 4.