The Scientific and Historical Value of Annotations on Astronomical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The HERACLES View of the H -To-HI Ratio in Galaxies

The HERACLES View of the H2-to-HI Ratio in Galaxies Adam Leroy (NRAO, Hubble Fellow) Fabian Walter, Frank Bigiel, the HERACLES and THINGS teams The Saturday Morning Summary • Star formation rate vs. gas relation on ~kpc scales breaks apart into: A relatively universal CO-SFR relation in nearby disks Systematic environmental scalings in the CO-to-HI ratio • The CO-to-HI ratio is a strong function of radius, total gas, and stellar surface density correlated with ISM properties: dust-to-gas ratio, pressure harder to link to dynamics: gravitational instability, arms • Interpretation: the CO-to-HI ratio traces the efficiency of GMC formation Density and dust can explain much of the observed behavior heracles Fabian Walter Erik Rosolowsky MPIA UBC Frank Bigiel Eva Schinnerer UC Berkeley THINGS plus… MPIA Elias Brinks Antonio Usero Gaelle Dumas U Hertfordshire OAN, Madrid MPIA Erwin de Blok Andreas Schruba Helmut Wiesemeyer U Cape Town IRAM … MPIA Rob Kennicutt Axel Weiss Karl Schuster Cambridge MPIfR IRAM Barry Madore Carsten Kramer Karin Sandstrom Carnegie IRAM MPIA Michele Thornley Daniela Calzetti Kelly Foyle Bucknell UMass MPIA Collaborators The HERA CO-Line Extragalactic Survey First maps Leroy et al. (2009) • IRAM 30m Large Program to map CO J = 2→1 line • Instrument: HERA receiver array operating at 230 GHz • 47 galaxies: dwarfs to starbursts and massive spirals -2 • Very wide-field (~ r25) and sensitive (σ ~ 1-2 Msun pc ) NGS The HI Nearby Galaxy Survey HI Walter et al. (2008), AJ Special Issue (2008) • VLA HI maps of 34 galaxies: -

Resource Letter OSE-1: Observing Solar Eclipses Jay M

Resource Letter OSE-1: Observing Solar Eclipses Jay M. PasachoffAndrew Fraknoi Citation: American Journal of Physics 85, 485 (2017); doi: 10.1119/1.4985062 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.4985062 View Table of Contents: http://aapt.scitation.org/toc/ajp/85/7 Published by the American Association of Physics Teachers RESOURCE LETTER Resource Letters are guides for college and university physicists, astronomers, and other scientists to literature, websites, and other teaching aids. Each Resource Letter focuses on a particular topic and is intended to help teachers improve course content in a specific field of physics or to introduce nonspecialists to this field. The Resource Letters Editorial Board meets annually to choose topics for which Resource Letters will be commissioned during the ensuing year. Items in the Resource Letter below are labeled with the letter E to indicate elementary level or material of general interest to persons seeking to become informed in the field, the letter I to indicate intermediate level or somewhat specialized material, or the letter A to indicate advanced or specialized material. No Resource Letter is meant to be exhaustive and complete; in time there may be more than one Resource Letter on a given subject. A complete list by field of all Resource Letters published to date is at the website <http://ajp.dickinson.edu/ Readers/resLetters.html>. Suggestions for future Resource Letters, including those of high pedagogical value, are welcome and should be sent to Professor Mario Belloni, Editor, AJP Resource Letters, Davidson College, Department of Physics, Box 6910, Davidson, NC 28035; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Lomonosov, the Discovery of Venus's Atmosphere, and Eighteenth Century Transits of Venus

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 15(1), 3-14 (2012). LOMONOSOV, THE DISCOVERY OF VENUS'S ATMOSPHERE, AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TRANSITS OF VENUS Jay M. Pasachoff Hopkins Observatory, Williams College, Williamstown, Mass. 01267, USA. E-mail: [email protected] and William Sheehan 2105 SE 6th Avenue, Willmar, Minnesota 56201, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The discovery of Venus's atmosphere has been widely attributed to the Russian academician M.V. Lomonosov from his observations of the 1761 transit of Venus from St. Petersburg. Other observers at the time also made observations that have been ascribed to the effects of the atmosphere of Venus. Though Venus does have an atmosphere one hundred times denser than the Earth’s and refracts sunlight so as to produce an ‘aureole’ around the planet’s disk when it is ingressing and egressing the solar limb, many eighteenth century observers also upheld the doctrine of cosmic pluralism: believing that the planets were inhabited, they had a preconceived bias for believing that the other planets must have atmospheres. A careful re-examination of several of the most important accounts of eighteenth century observers and comparisons with the observations of the nineteenth century and 2004 transits shows that Lomonosov inferred the existence of Venus’s atmosphere from observations related to the ‘black drop’, which has nothing to do with the atmosphere of Venus. Several observers of the eighteenth-century transits, includ- ing Chappe d’Auteroche, Bergman, and Wargentin in 1761 and Wales, Dymond, and Rittenhouse in 1769, may have made bona fide observations of the aureole produced by the atmosphere of Venus. -

Historical & Cultural Astronomy

Historical & Cultural Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman W. BUTLER BURTON, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA ([email protected]); University of Leiden, The Netherlands, ([email protected]) JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound, USA MILLER GOSS, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA JAMES LEQUEUX, Observatoire de Paris, France SIMON MITTON, St. Edmund’s College Cambridge University, UK WAYNE ORCHISTON, National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, Thailand MARC ROTHENBERG, AAS Historical Astronomy Division Chair, USA VIRGINIA TRIMBLE, University of California Irvine, USA XIAOCHUN SUN, Institute of History of Natural Science, China GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Institute for History of Science and Technology, Germany More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15156 Alexus McLeod Astronomy in the Ancient World Early and Modern Views on Celestial Events 123 Alexus McLeod University of Connecticut Storrs, CT USA ISSN 2509-310X ISSN 2509-3118 (electronic) Historical & Cultural Astronomy ISBN 978-3-319-23599-8 ISBN 978-3-319-23600-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-23600-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016941290 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

International Comet Quarterly

International Comet Quarterly Links International Comet Quarterly ICQ: Recommended (and condemned) sources for stellar magnitudes Cometary Science Center Comet magnitudes Below is a list that observers may use to evaluate whether the source(s) that they are Central Bureau for Astro. Tel. contemplating using for visual or V stellar magnitudes are recommended or not. Unfortunately, many errors have been found over the years in the both the individual variable-star charts of Minor Planet Center the AAVSO (ICQ code AC) and the AAVSO Variable Star Atlas (code AA); those variable-star EPS/Harvard charts were designed for the purpose of tracking the relative variation in brightness of individual variable stars, and they frequently are not adequately aligned with the proper magnitude scale. The new Hipparcos/Tycho catalogues have had new codes implemented (see below). New additions (and changes in categories) will be made to the following list as new information reaches the ICQ. MAGNITUDE-REFERENCE KEY Second-draft recommendation list, 1997 Dec. 1. Updated 2007 April 20 and 2017 Oct. 4. NOTE: For visual magnitude estimation of comets, NEVER USE SOURCES for which the available star magnitudes are only brighter than the comet! For example, the SAO Star Catalog is very poor for magnitudes fainter than 9.0, and should NEVER be used on comets fainter than mag 9.5. The Tycho catalogue should not be used for comets fainter than mag 10.5. (Even CCD photometrists should be wary of using bright stars for very faint comets; it is always best to use comparison stars within a few magnitudes of the comet when doing CCD photometry.) NOTE: It is highly recommended that users of variable-star charts also specify (in descriptive notes to accompany the tabulated data) the specific chart(s) used for each observation; this information will be published in the ICQ. -

Volume 35 E-Mail: [email protected] Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2015

The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy Volume 35 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2015 Letter from Florence It’s the end of June 2015, and Anna and I are preparing to leave Mensola, and Boccaccio and Petrarca, and Laura Battiferra I Tatti for the last time. It has been an intense and wonderful too. We are grateful to all of them for opening our eyes to five-year period at the Villa, with exceptional groups of the beauty of this valley, and enhancing the experience of our Fellows, Visiting Professors, and guests joining us from all walk with their words. corners of the world. And it has seemed a very quick period, too. The last year has gone in a flash. It seems only yesterday Our walk also offers us a chance to talk about what’s going on that we were harvesting our grapes, and already our vineyards in the day, the ups and downs, the ins and outs of la vita tattiana: are once more covered in luxuriant foliage while the olive who is leaving, and who is coming next to I Tatti, the lectures, groves are rich with the promise of new oil for the fettunta. conferences, and concerts in preparation, and the books that Anna and I love this little Mensola valley and never miss an have just appeared and those that are due out soon. But it’s opportunity to admire the beautiful, peaceful order in which also a marvelous opportunity to see how the restoration of the everything – vigne, oliveti, giardini e case – is kept by our staff. -

The Icha Newsletter Newsletter of the Inter-Union Commission For

International Astronomical Union International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science DHS/IUHPS ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE ICHA NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER OF THE INTER-UNION COMMISSION FOR HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY* ____________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ No. 11 – January 2011 SUMMARY A. Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy: Building Bridges between Cultures – IAU Symposium S278 Report by C. Ruggles ..................................................... 1 B. Historical Observatory building to be restored by A. Simpson …..…..…...… 5 C. History of Astronomy in India by B. S. Shylaja ……………………………….. 6 D. Journals and Publications: - Acta Historica Astronomiae by Hilmar W. Duerbeck ................................ 8 Books 2008/2011 ............................................................................................. 9 Some research papers by C41/ICHA members - 2009/2010 ........................... 9 E. News - Exhibitions on the Antikythera Mechanism by E. Nicolaidis ……………. 10 - XII Universeum Meeting by M. Lourenço, S. Talas, R. Wittje ………….. 10 - XXX Scientific Instrument Symposium by K.Gaulke ..………………… 12 F. ICHA Member News by B. Corbin ………………………………………… 13 * The ICHA includes IAU Commission 41 (History of Astronomy), all of whose members are, ipso facto, members of the ICHA. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Astronomy Magazine Special Issue

γ ι ζ γ δ α κ β κ ε γ β ρ ε ζ υ α φ ψ ω χ α π χ φ γ ω ο ι δ κ α ξ υ λ τ μ β α σ θ ε β σ δ γ ψ λ ω σ η ν θ Aι must-have for all stargazers η δ μ NEW EDITION! ζ λ β ε η κ NGC 6664 NGC 6539 ε τ μ NGC 6712 α υ δ ζ M26 ν NGC 6649 ψ Struve 2325 ζ ξ ATLAS χ α NGC 6604 ξ ο ν ν SCUTUM M16 of the γ SERP β NGC 6605 γ V450 ξ η υ η NGC 6645 M17 φ θ M18 ζ ρ ρ1 π Barnard 92 ο χ σ M25 M24 STARS M23 ν β κ All-in-one introduction ALL NEW MAPS WITH: to the night sky 42,000 more stars (87,000 plotted down to magnitude 8.5) AND 150+ more deep-sky objects (more than 1,200 total) The Eagle Nebula (M16) combines a dark nebula and a star cluster. In 100+ this intense region of star formation, “pillars” form at the boundaries spectacular between hot and cold gas. You’ll find this object on Map 14, a celestial portion of which lies above. photos PLUS: How to observe star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies AS2-CV0610.indd 1 6/10/10 4:17 PM NEW EDITION! AtlAs Tour the night sky of the The staff of Astronomy magazine decided to This atlas presents produce its first star atlas in 2006. -

Chapter I Review Papers Harlow Shapley

Chapter I Review Papers Harlow Shapley Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:30:59, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0074180900042340 Helen Sawyer Hogg and Willis Shapley remembering Willis Shapley fielding questions on his father Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:30:59, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0074180900042340 SHAPLEY'S DEBATE Michael Hoskin Cambridge University The attempt to make three-dimensional sense of the Milky Way goes back to a most unlikely origin: the English antiquary of the early eighteenth century, William Stukeley, remembered today for associating the Druids with Stonehenge. Stukeley came from Lincolnshire and so was a fellow-countryman of Isaac Newton, and as a result he was privileged to talk with the great man from time to time. In his Memoirs of Newton Stukeley records one conversation they had in about 1720, in which Stukeley proposed that the Sun and the brightest stars of the night sky make up what we today would term a globular cluster, and this cluster is surrounded by a gap, outside of which lie the small stars of the Milky Way in the form of a flattened ring. Stukeley's remarkable suggestion was recorded only in his manuscript memoirs, and had no effect on the subsequent history of astronomy. -

Our Milky Way.Key

Our Milky Way Learning Objectives ! What is the Milky Way? The Herschels thought we were at the center of our Galaxy...why were they wrong? ! How did Shapley prove we aren’t at the center? What are globular clusters? Cepheid Variable stars? ! How do we use Cepheid Variables to measure distance? ! What are the components of our Galaxy? What color are old stars? Young stars? Does our Galaxy get older or younger as you move out (i.e. from the disk to the halo)? ! How do we know our Galaxy is a spiral galaxy? ! Do stars in our Galaxy’s disk orbit as Kepler’s Laws would predict? What is a rotation curve? Why does our Galaxy’s rotation curve suggest dark matter exists? The Milky Way ! Our Galaxy is a collection of stars, nebulae, molecular clouds, and stellar remnants ! All bound together by gravity ! Connected by the stellar evolution cycle Determining the Shape of our Galaxy ! The number of 6400 ly stars were counted in all directions from 1300 ly the Sun by Sun Caroline Herschel and her brother William ! They assumed that all stars have the same brightness and that space contains no dust – these are incorrect assumptions ! They thus concluded that the Sun is at the center of the Universe - which is not true The Importance of Dust ! Dust dims and reddens starlight ! There is more dust toward the center of the Galaxy ! Consequence: We underestimate the number of stars in one direction ! We appear to be near the center, but we’re not Us Star Sun Can’t see stars here (if we’re looking for blue light from them) How Do We Find the Galactic Center? -

At the Harvard Observatory

Book Reviews 117 gravitational wave physicists, all of whom are members of an international group of over a thousand scientists engaged with the detection apparatus at two widely separated sites, one in Livingston, Louisiana and the other in Hanford, Washington. The emails research- ers in the collaboration exchanged and the queries Collins sent to the physicists who acted for him as “key informants” provide the bulk of the material for Collins’ “real- time” observations of this discovery in the making. At times, Collins finds the community of researchers exasperating and wrong-headed in their, in his view, overly secretive attitudes to their results. But Collins is not a detached witness of the events he describes and analyses. Instead, he is overall a highly enthusias- tic fan of the gravitational wave community. Collins has not sought out for Gravity’s Kiss the kinds of evidence one might have expected a historian to have pursued. Gravity’s Kiss, however, should be read on its terms. It is a work of reportage from an “embedded” sociologist of science with long experience of, and valuable connections in, the gravitational wave community. Along the way, he offers sharp insights into the work- ing of these scientists. Collins proves to be an excellent guide to the operations of a “Big Science” collaboration and the intense scrutiny of, and complicated negotiations around, the “[v]ery interesting event on ER8.” Robert W. Smith University of Alberta [email protected] “Girl-Hours” at the Harvard Observatory The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. -

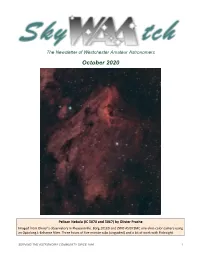

October 2020

The Newsletter of Westchester Amateur Astronomers October 2020 Pelican Nebula (IC 5070 and 5067) by Olivier Prache Imaged from Olivier’s observatory in Pleasantville. Borg 101ED and ZWO ASI071MC one-shot-color camera using an Optolong L-Enhance filter. Three hours of five-minute subs (unguided) and a bit of work with PixInsight. SERVING THE ASTRONOMY COMMUNITY SINCE 1986 1 Westchester Amateur Astronomers SkyWAAtch October 2020 WAA October Meeting WAA November Meeting Friday, October 2 at 7:30 pm Friday, November at 6 7:30 pm On-line via Zoom On-line via Zoom Intelligent Nighttime Lighting: The Many BLACK HOLES: Not so black? Benefits of Dark Skies Willie Yee Charles Fulco Recent years have seen major breakthroughs in the Science educator Charles Fulco will discuss the meth- study of black holes, including the first image of a ods and many benefits of reducing light pollution, black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope and the including energy and tax dollar savings, health bene- detection of black hole collisions with the Laser fits and of course seeing the Milky Way again. Invita- Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory. tions and log-in instructions will be sent to WAA Dr. Yee, a NASA Solar System Ambassador and Past members via email. President of the Mid-Hudson Astronomical Association, will review the basic science of black Starway to Heaven holes and the myths surrounding them, and present Ward Pound Ridge Reservation, the recent findings of these projects. Cross River, NY Call: 1-877-456-5778 (toll free) for announcements, Scheduled for Oct 10th (rain/cloud date Oct 17).