Dressing, Undressing, and Early European Contact in Australia and Tahiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Union

OFFICE OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL (OTEXA) Market Reports Textiles, Apparel, Footwear and Travel Goods European Union The following information is provided only as a guide and should be confirmed with the proper authorities before embarking on any export activities. Import Tariffs The EU is a customs union that provides for free trade among its 28 member states--Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and The United Kingdom. The EU levies a common tariff on imported products entered from non-EU countries. By virtue of the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU), Belgium and Luxembourg are considered a single territory for the purposes of customs and excise. The United Kingdom (UK) withdrew from the EU effective February 1, 2020. During the transition period, which ends on December 31, 2020, EU law continues to be applicable to and in the UK. Any reference to Member States shall be understood as including the UK where EU law remains applicable to and in the UK until the end of the transition period according to the Withdrawal Agreement (OJ C 384 1, 12.11.2019, p. 1). EU members apply the common external tariff (CET) to goods imported from non-EU countries. Import duties are calculated on an ad valorem basis, i.e., expressed as a percentage of the c.i.f. (cost, insurance and freight) value of the imported goods. EU: Tariffs (percent ad valorem) on Textiles, Apparel, Footwear and Travel Goods HS Chapter/Subheading Tariff Rate Range (%) Yarn -silk 5003-5006 0 - 5 -wool 5105-5110 2 - 5 -cotton 5204-5207 4 - 5 -other vegetable fiber 5306-5308 0 - 5 -man-made fiber 5401-5406/5501-5511 3.8 - 5 ....................... -

Endeavour Anniversary

Episode 10 Teacher Resource 28th April 2020 Endeavour Anniversary Students will investigate Captain Endeavour History Cook’s voyage to Australia on 1. When did the Endeavour set sail from England? board the HMB Endeavour. Students will explore the impact 2. Who led the voyage of discovery on the Endeavour? that British colonisation had on 3. Describe James Cook’s background. the lives of Aboriginal and Torres 4. What did Cook study that would help him to become a ship’s Strait Islander Peoples. captain? 5. Fill in the missing words: By the 18th Century, _________________ had been mapping the globe for centuries, claiming HASS – Year 4 ______________ and resources as their own. (Europeans and land) The journey(s) of AT LEAST ONE 6. Who was Joseph Banks? world navigator, explorer or trader 7. Why did Banks want to travel on the Endeavour? up to the late eighteenth century, including their contacts with other 8. The main aim of the voyage was to travel to… societies and any impacts. 9. What rare event was the Endeavour crew aiming to observe? 10. What was their secret mission? The nature of contact between 11. Who was Tupaia? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and others, for 12. After leaving Tahiti, where did the Endeavour go? example, the Macassans and the 13. What happen in April 1770? Europeans, and the effects of 14. Complete the following sentence. Australia was known to Europeans these interactions on, for at the time as New___________________. (Holland) example, people and environments. 15. Describe the first contact with Indigenous people. -

Donated Goods Value Sheet

3927 1st Ave. South Billings, MT 59101 (406) 259-2269 Estimated Value of Donated Property Guidelines This is merely a guideline to assist you in determining values for your own items. You must take into consideration the quality and condition of your items when determining a value. T he IRS does not allow Family Service staff to assign a dollar valuation. We can only verify your gif t, so be sure to pick up a donation receipt when the goods are dropped off. Acc ording to IRS regulations and tax code, clothing and household goods must be in “good condition or better” for tax deductions. Women’s Clothing Men’s Clothing Item Low Range High Range Item Low Range High Range Top/Shirt/Blouse $3.00 $15.00 Jacket $8.00 $30.00 Bathrobe $5.00 $15.00 Overcoat $15.00 $60.00 Bra $1.00 $5.00 Pajamas $2.00 $8.00 Bathing Suit $4.00 $15.00 Pants, Shorts $4.00 $10.00 Coat $10.00 $70.00 Raincoat $6.00 $24.00 Dress $5.00 $20.00 Suit $15.00 $70.00 Evening Dress $10.00 $40.00 Slacks/Jeans $4.00 $25.00 Fur Coats $25.00 $300.00* Shirt $3.00 $8.00 Handbag $1.00 $50.00 Sweater $3.00 $10.00 Hat $1.00 $5.00 Swim trunks $3.00 $5.00 Jacket $4.00 $20.00 Tuxedo $15.00 $40.00 Nightwear/Pajamas $4.00 $10.00 Undershirt/T-shirt $1.00 $2.00 Sock $1.00 $1.50 Undershorts $1.00 $1.50 Skirt $3.00 $20.00 Belt $1.00 $8.00 Sweater $3.00 $25.00 Tie $1.00 $2.00 Slip $1.00 $5.00 Socks $1.00 $1.50 Slacks/Jeans $4.00 $35.00 Hat/Cap $1.00 $5.00 Suit – 2 pc. -

Parent/Camper Guide YMCA CAMP at HORSETHIEF RESERVOIR

BEST CAMP EVER Parent/Camper Guide YMCA CAMP AT HORSETHIEF RESERVOIR www.ycampidaho.org In here you will find information on: Directions to Y Camp Check In/Check Out Procedures Payment/Cancellation Information Communication with Your Camper Open House Homesickness Dress Code & Packing List Financial Assistance requirements by ensuring that all children are super- CHECK IN PROCEDURES vised and accounted for at all times and that any camp WELCOME TO Y CAMP! Bus transportation from Boise and back is $10 each visitors are immediately greeted and accompanied. Rest Thank you for choosing YMCA Camp at Horsethief Reservoir this summer! By registering your camper for a week at way, non-refundable one week prior to camp. Guardians assured that your camper is in good hands. Y Camp you have begun a journey that will change their life in more ways than you might imagine. are encouraged to pick their camper up from camp if possible so they may show you around and join them for YMCA Camp at Horsethief Reservoir engages volunteer Y Camp is a place of magic and wonder, where under the tutelage of our highly trained staff, your camper will ex- lunch. medical staff for each session of camp. These volun- perience new activities and learn new skills with an emphasis on developing the YMCA core values of Caring, Hon- teers hold a current RN certification. Our medical staff esty, Respect, and Responsibility. While experiencing fun and exciting adventures, campers will learn more about Changes to transportation requests must be made no are responsible for all aspects of health management themselves and build friendships and memories to last a lifetime. -

Kamay Botany Bay National Park Planning Considerations

NSW NATIONAL PARKS & WILDLIFE SERVICE Kamay Botany Bay National Park Planning Considerations environment.nsw.gov.au © 2020 State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. DPIE shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by DPIE and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. DPIE asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Department of Planning, Industry -

Hawkesworth's Voyages and the Literary Influence on Erasmus

Hawkesworth’s Voyages and the Literary Influence on Erasmus Darwin’s The Loves of the Plants Ayako WADA* Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), famously known as a grandfather of Charles Darwin (1809-82), was a talented man of multiple disciplines as Desmond King-Hele breaks down his achievements into four spheres ‘as a doctor, an inventor and technologist, a man of science and a writer’.1 While he was a physician by profession, he was also a founder of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, the human network of which, including such pioneering engineers as Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) and James Watt (1736-1819), accelerated the Industrial Revolution. Also, Darwin was a believer in biological evolution, the rudimentary idea of which was made explicit in Zoonomia (1794-96). 2 As for Darwin’s literary achievements, in spite of its short-lived success, The Botanic Garden (1791) made him most popular during the 1790s and saw ‘four English editions along with separate Irish and American printings by 1799 … translated into French, Portuguese, Italian, and German’ as Alan Bewell summarised.3 Although King-Hele indicates how English Romantic poets were indebted to Darwin,4 they are also known to have been both attracted and repulsed by his poetics, as revealed in their writings.5 The purpose of this article is to illuminate the still imperfectly understood aspect of Darwin’s most influential work entitled The Loves of the Plants (1789)—first published as the second part of The Botanic Garden (1791)—in terms of its link to An Account of the Voyages (1773), edited by his immediate predecessor, John Hawkesworth (1720-73). -

Captain Cook's Voyages

National Library of Ireland Prints and Drawings Collection List Captain Cook Voyages Plate Collection Collection comprised of plates showing the Voyages of Captain Cook, which form part of the Joly Collection held by the Department of Prints and Drawings. The collection also contains prints from a number of different publications relating to Cook’s voyages. Compiled by Prints and Drawings Department 2008 Joly Collection – Captain Cook’s Voyages Introduction This list details the plates showing the Voyages of Captain Cook, which form part of the Joly Collection held by the Department of Prints and Drawings. The collection contains prints from a number of different publications relating to Cook’s voyages. The plates have been divided by the volume they relate to, and then arranged, where possible, in the order they are found in the printed work. The plates in this collection cover the three voyages of Captain Cook; 1768-71, 1772-5 and 1776-9. On each voyage Cook was accompanied by a different artist, and it is on their drawings that the plates are based. On the first voyage Captain Cook was accompanied by Sydney Parkinson, who died shortly before the end of the voyage. William Hodges replaced Parkinson on the second voyage and the third voyage was covered by John Webber. Sydney Parkinson’s Illustrations, 1773 These plates come from A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in his Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour faithfully transcribed from the papers of the late Sydney Parkinson published in London in 1773. It covers the first voyage of Captain Cook, the set is complete except for Plate XXV Map of the Coast of New Zealand discovered in the Years 1769 and 1770 . -

Artistic Endeavour – Room Brochure

Contemporary botanical artists’ response to the legacy of Banks, Solander and Parkinson Front cover: Anne Hayes, Banksia serrata, old man banksia, gabiirr (Guugu Yimithirr), 2017, watercolour on paper, 63 x 45 cm Pages 2–3: Penny Watson, Goodenia rotundifolia, round leaved goodenia, 2018, watercolour on paper, 26 x 43 cm Pages 5 and 9: Ann Schinkel, Bauera capitata, dog rose, (details), 2019, watercolour on paper, 26 x 15 cm Page 7: Florence Joly, Melaleuca viminalis, weeping bottlebrush, garra (group name, Yuggara), (detail), 2019, graphite, colour pencil on paper, 33 x 66 cm Pages 10–11: Minjung Oh, Pleiogynium timorense, Burdekin plum, (detail), 2018, watercolour on paper, 59 x 46 cm © The artists and authors For information on the exhibition tour, go to the M&G QLD website http://www.magsq.com.au/cms/page.asp?ID=10568 BASQ website www.botanicalartqld.com.au Artistic Endeavour is an initiative of the Botanical Artists’ Society of Queensland in partnership with Museums & Galleries Queensland. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government’s Visions of Australia program; the Queensland Government through the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, state and territory governments; and the Regional Arts Development Fund, a partnership between the Queensland Government and Moreton Bay Regional Council to support local arts and culture in regional Queensland. Proudly supported by Moreton Bay Regional Council and sponsored by IAS Fine Art Logistics and Winsor & Newton. Artists Artistic Endeavour Gillian Alfredson Artistic Endeavour: Contemporary botanical artists’ response Catherin Bull to the legacy of Banks, Solander and Parkinson marks the 250th Edwin Butler anniversary of the HMB Endeavour voyage along the east coast of Australia. -

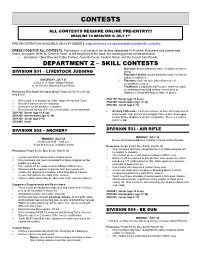

2021 Contests

CONTESTS ALL CONTESTS REQUIRE ONLINE PRE-ENTRY!!! DEADLINE TO REGISTER IS JULY 1ST PRE-REGISTRATION AVAILABLE ON OUR WEBSITE: http://extension.unl.edu/statewide/saunders/4hcountyfair/ DRESS CODE FOR ALL CONTESTS: Participants in all contests are to wear sponsored 4-H t-shirts, blue jeans and closed-toed shoes. No shorts. Refer to “General Rules” at the beginning of the book. No shooting jackets will be permitted. Exception = Best Dressed Critter Contest, Favorite Foods, Fashion Show, and the County Fair Parade DEPARTMENT Z – SKILL CONTESTS o Barebow: arrows drawn by hand, no sights on bow or DIVISION 501 – LIVESTOCK JUDGING string. o Freestyle Limited: arrows drawn by hand, no limit on sights or stabilizers. SATURDAY, JULY 31 o Freestyle: same as limited but allows use of 4:30 p.m. in Gayle Hattan Pavilion mechanical releases. or 30 minutes following Round Robin o Traditional: Long bows and Recurve bows; no sights or markings of any kind on bow, no releases or Premiums (For Youth Divisions Only): Purple $3.00; Blue $2.00; stabilizers. Shoot with fingers, tabs, or gloves. Red $1.00 Z502100 Senior (age 15 & up) Will consist of evaluation of Cattle, Hogs, Sheep and Goats. Z502200 Intermediate (age 12-14) At least 4 classes will be evaluated Z502300 Junior (age 8-11) Questions will be asked on 2 classes. Divisions will consist of Senior, Intermediate, Junior and Adult. • Archery Club note – Youth do not have to have their own bow to Z501100 Senior (age 15 & up) practice with club, but it is encouraged. Parents are encouraged Z501200 Intermediate (age 12-14) to stay for the duration of an archery practice. -

Textiles for Dress 1800-1920

Draft version only: not the publisher’s typeset P.A. Sykas: Textiles for dress 1800-1920 Textile fabrics are conceived by the manufacturer in terms of their material composition and processes of production, but perceived by the consumer firstly in terms of appearance and handle. Both are deeply involved in the economic and cultural issues behind the wearing of cloth: cost, quality, meaning. We must look from these several perspectives in order to understand the drivers behind the introduction of fabrics to the market, and the collective response to them in the form of fashion. A major preoccupation during our time frame was novelty. On the supply side, novelty gave a competitive edge, stimulated fashion change and accelerated the cycle of consumption. On the demand side, novelty provided pleasure, a way to get noticed, and new social signifiers. But novelty can act in contradictory ways: as an instrument for sustaining a fashion elite by facilitating costly style changes, and as an agent for breaking down fashion barriers by making elite modes more affordable. It can drive fashion both by promoting new looks, and later by acting to make those looks outmoded. During the long nineteenth century, the desire for novelty was supported by the widely accepted philosophical view of progress: that new also implied improved or more advanced, hence that novelty was a reflection of modernity. This chapter examines textiles for dress from 1800 to 1920, a period that completed the changeover from hand-craft to machine production, and through Europe’s imperial ambitions, saw the reversal of East/West trading patterns. -

Children's Nightwear & Fire Safety

Children's nightwear and a limited amount of daywear must now comply with Australian Standard AS/NZS 1249:1999 which reduces CHILDREN’S the fire hazard of clothing. NIGHTWEAR Fire Warning Labels Items covered in the mandatory labelling & FIRE SAFETY requirements include styled and recognised nightwear garments such as pyjamas, pyjama-style overgarments, nightdresses, nightshirts, dressing gowns, bathrobes, infant sleepbags and boxer shorts of a loose style. Garments must be flammability tested before being labelled. Garments are categorised according to fabric type and burning behaviour. Low Fire Danger Garments made with this label are made to In 1979 a staggering 300 Australian children be slow burning: were admitted to hospital after being burned when nightclothes caught fire. Flimsy, loose- fitting girls’ nighties were often involved. LOW FIRE DANGER These would swirl into contact with flames or hot surfaces and burn quickly. A number of prevention efforts, including a change to the x Made from material that is difficult to Australian Standard for warning labels, have ignite, such as wool, and some nylon and led to a major reduction in injuries. polyester. x Styled to reduce fire danger (such as close-fitting tracksuit styles). Did you know? x Pass stringent restrictions on trim sizing, It is illegal in Australia to which limits the risk of flames spreading. sell size 0-14 children's High Fire Danger nightgowns made from 100% Chenille Garments with the following label pass Or Australian Standards, but present a higher fire risk. They are not subject to restrictions 100% Cotton Flannelette on styling or trims, and are made with a combination of flammable fabrics. -

Ellen Poncho No

Ellen Poncho No. 2004-184-5320 Materials Pattern information 6 skeins of 50 g Soft Alpaca The poncho is knit from the top down. Circular needles US 2 ½ (3.0mm) 24”, 32”, 40” The increase stitches should line up on top of each other. You can use a stitch marker to help with this. Gauge Change lengths of circular needles as needed when the stitches become too crowded. 25 sts = 4” Abbreviations for Increases Size M1 (knitwise): From the front, lift loop One size between stitches with left needle, knit into back Neck opening: Approx. 21” of loop. M1 (purlwise): From the front, lift loop between stitches with left needle, purl into Buy the yarn here back of loop. P1 f&b: Purl a stitch, leaving stitch on left http://shop.hobbii.com/ellen-poncho needle; purl into the back loop of this stitch. K1 f&b: Knit a stitch, leaving stitch on left needle; knit into the back loop of this stitch. Hobbii.com - Copyright © 2018 - All rights reserved. Page 1 Pattern Neck CO 128sts on 24” circular needles US 2 ½ and knit in garter stitch in the round: Rnd 1: Knit all sts Rnd 2: Purl all sts Repeat these 2 rnds until there are 3 ridges. Continue in pattern with increases: K 32, place marker = middle front, K 63, place marker = middle back, K to the end. Rnd 1: K to marker, M1 knitwise, K1, M1 knitwise, K to next marker, M1 knitwise, K1, M1 knitwise, K to end of rnd. Rnd 2: Knit all sts. Rnd 3: K to marker, M1 knitwise, K1, M1 knitwise, K to next marker, M1 knitwise, K1, M1 knitwise, K to end of rnd.