White Mountain National F Orest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race Results for William Bruneau-Bouchard

Race Results for William Bruneau-Bouchard - ALP - GS Race Race Race USSA Code Event Date Event Name Event Location Rank Time Points Points U0816 3/10/2021 2021 NCAA National Collegiate Mittersill Cannon 19 02:05.91 36.06 257.18 Skiing Championship Mountain, NH F1235 2/26/2021 SLU FIS-U Whiteface Mountain, NY 7 01:56.23 7.53 44.41 F1236 2/26/2021 SLU FIS-U Whiteface Mountain, NY 5 02:05.93 15.89 50.46 F0976 2/23/2021 Divisional FIS Mittersill Cannon 7 02:15.61 2.99 38.34 Mountain, NH F0488 1/25/2021 Divisional FIS Waterville Valley Resort, 3 01:56.27 8.14 40.38 NH U0171 3/11/2020 2020 NCAA National Collegiate Bridger Bowl Ski Area, MT 17 01:49.10 20.50 60.50 Skiing Championship F0575 3/6/2020 Men's Eastern Cup Waterville Valley Resort, 17 01:55.83 19.74 45.65 NH F0574 3/5/2020 Men's Eastern Cup Waterville Valley Resort, 5 01:56.59 8.03 34.50 NH F0251 2/29/2020 Middlebury Carnival - EISA Middlebury College Snow 15 02:05.42 33.36 50.91 Regional Champs Bowl, VT F0564 2/14/2020 Williams Winter Carnival Jiminy Peak Mountain 11 01:43.96 10.21 33.70 Resort, MA F0143 2/8/2020 Bates Carnival - EISA Sunday River Resort, ME 14 02:17.13 21.28 43.34 F0155 1/31/2020 Colby Carnival - EISA Sugarloaf, ME 9 02:01.52 18.62 42.43 F0233 1/24/2020 UVM Carnival - EISA Stowe Mountain Resort / 6 02:14.23 12.26 35.52 Spruce Peak, VT F0223 1/18/2020 Harvard Carnival - EISA Waterville Valley Resort, 10 02:09.17 15.32 39.89 NH F0386 1/7/2020 NorAm Cup #3 Stowe Mountain Resort / 48 02:04.08 41.08 61.57 Spruce Peak, VT F0385 1/6/2020 NorAm Cup #3 Stowe Mountain Resort / 39 02:05.77 42.34 61.19 Spruce Peak, VT F0056 1/5/2020 NorAm Cup #2 Burke Mountain, VT 46 01:26.04 46.15 64.27 F0375 4/3/2019 Eastern Cup Burke Mountain, VT 7 02:13.25 11.11 21.82 U1239 3/30/2019 UNH Fundraiser Loon Mountain Ski Resort, 6 01:39.77 22.14 58.48 NH F0659 3/26/2019 U.S. -

Tripoli East Vegetation Management Project EA 2.0 Chapter 3 – Page I

United States Department of TRIPOLI EAST Agriculture Forest Service VEGETATION March 2003 MANAGEMENT PROJECT Towns of Livermore and Thornton Grafton County, New Hampshire Environmental Assessment 2.0 Prepared By Ammonoosuc/Pemigewasset Ranger District, White Mountain National Forest For Information Contact: Susan Wingate Ammonoosuc/Pemigewasset Ranger District White Mountain National Forest RFD #3, Box 15 Plymouth, NH 03264-9103 603-536-1315 www.fs.fed.us/r9/white Tripoli East Vegetation Management Project EA 2.0 Chapter 3 – page i This document is available in large print. Contact the White Mountain National Forest Supervisor’s Office 1-603-528-8721 TTY 1-603-528-8722 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political affiliation, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status (not all prohibited bases apply to all programs). Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication or program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact the USDA's TARGET Center at 202/720-2600 (voice or TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write the USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, Washington, DC, 20250-9410 or call 202/720-5964 (voice or TDD). The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on Recycled Paper Page ii Tripoli East Vegetation Management Project EA 2.0 TRIPOLI -

Bethlehem Master Plan 2016

MASTER PLAN 2016 B ETHLEHEM NH D r a f t P l a n December 18 , 2 0 1 6 Bethlehem Master Plan 2016 “If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.” -Benjamin Franklin “You can design and create, and build the most wonderful place in the world. But it takes people to make the dream a reality.” -Walt Disney Cover Photo Credit: Bethlehem Mural; located at outside at WREN in the Bethlehem Village District; all cover photos by Mike Bruno Page 2 Bethlehem Master Plan - Table of Contents Bethlehem Master Plan 2016 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 VISION STATEMENT ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GOALS & OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................................................... 10 PLANNING HISTORY ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study June 2011 USDA Forest Service White Mountain National Forest Appalachian Mountain Club Plymouth State University Center for Rural Partnerships U.S. Department of Transportation, John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 09/22/2011 Study September 2009 - December 2011 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study 09-IA-11092200-037 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Alex Linthicum, Charlotte Burger, Larry Garland, Benoni Amsden, Jacob 51VXG70000 Ormes, William Dauer, Ken Kimball, Ben Rasmussen, Thaddeus 5e. TASK NUMBER Guldbrandsen JMC39 5f. -

Race Results for Christopher Golden

Race Results for Christopher Golden - ALP - GS Race Race Race USSA Code Event Date Event Name Event Location Rank Time Points Points F0147 4/11/2021 Western Region FIS Spring Series Squaw Valley / Alpine DNF2 990.00 Meadows, CA F0145 4/10/2021 Western Region FIS Spring Series Squaw Valley / Alpine 11 01:55.59 12.65 45.62 Meadows, CA F0993 3/24/2021 Divisional FIS Sugarloaf, ME DNF1 990.00 F1428 3/22/2021 Divisional FIS Waterville Valley Resort, NH DNF1 990.00 F0989 3/18/2021 Divisional FIS Sunday River Resort, ME 6 02:17.00 17.32 53.04 F0218 3/3/2021 Divisional FIS Attitash Mountain Resort, NH 31 02:14.09 30.02 62.67 F0976 2/23/2021 Divisional FIS Mittersill Cannon Mountain, NH DNF1 990.00 F1205 2/13/2021 Stowe FISU Burke Mountain, VT DNF2 990.00 F1206 2/13/2021 Stowe FISU Burke Mountain, VT 27 02:03.16 39.90 74.28 F0495 2/1/2021 Divisional FIS Attitash Mountain Resort, NH 5 02:08.27 17.79 53.80 F0496 2/1/2021 Divisional FIS Attitash Mountain Resort, NH DNS2 990.00 F0488 1/25/2021 Divisional FIS Waterville Valley Resort, NH 17 01:57.60 19.79 52.03 F0960 1/14/2021 Men's Divisional FIS Waterville Valley Resort, NH 27 02:06.88 46.81 79.48 F0959 1/13/2021 Men's Divisional FIS Waterville Valley Resort, NH DNF1 990.00 F0520 3/15/2020 Men's Devo FIS Series Gore Mountain, NY 21 02:14.30 29.65 69.75 F0519 3/14/2020 Men's Devo FIS Series Gore Mountain, NY 23 02:16.87 27.44 67.80 F0575 3/6/2020 Men's Eastern Cup Waterville Valley Resort, NH DNF2 990.00 F0574 3/5/2020 Men's Eastern Cup Waterville Valley Resort, NH 33 01:59.80 36.06 62.53 F0365 2/27/2020 NPS Snowbasin Resort, UT 33 02:08.09 47.73 85.67 F0362 2/25/2020 U.S. -

Layout 1 (Page

www.newhampshirelakesandmountains.com SERVING THE NORTH COUNTRY SINCE 1889 [email protected] 123RD YEAR, 1ST ISSUE LITTLETON, N.H., WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 4, 2012 75¢ (USPS 315-760) North Woodstock-based family remembers brother, sister By KHELA MCGANN Route 112. [email protected] Frank-Rand family ran Govoni’s restaurant since 1914 Lou’s two daughters WOODSTOCK — Lynda Frank Sanders and Fiercely loyal to family, Terry Frank Thompson and friends and community with Rita’s two sons, Gil and Paul a feistiness that seems to be Rand, grew up working in in every Italian’s DNA, the restaurant, which has Louis “Lou” Frank and his been closed for the past two sister, Rita Rand, left a legacy years but still has a chance of of civic commitment and reopening, the cousins said entrepreneurship in the Lin- recently. Wood area when they died They agreed that at least within months of each other 75 percent to 85 percent of last year. the restaurant’s business After 94 years of dream- was made up of repeat cus- ing up and participating in tomers. Though the menu new ventures — such as the eventually expanded, the Loon Mountain Ski Resort in family always stood by the 1960s and oil exploration Clementine and Melvina’s in the 1990s and 2000s — Louis “Lou” Frank passed away a original recipes for the pasta, little more than three months Rita Rand was the matriarch of Lou died Dec. 9, a little more PHOTO COURTESY OF THE FRANK-RAND FAMILIES sauce and meatballs, which than three months after his after his older sister, Rita. -

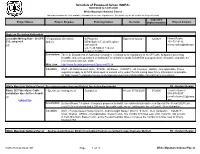

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2020 to 12/31/2020 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. White Mountain National Forest, Occurring in more than one District (excluding Forestwide) R9 - Eastern Region Route 302 Fiber Optic Cable - Special use management Completed Actual: 07/02/2020 07/2020 Jennifer Burnett Installation Special Use Permit 603-536-6237 CE jennifer.burnett2@usda. gov *UPDATED* Description: Bretton Woods Telephone Company proposes to install, use and maintain under new Special Use Permit (SUP) an aerial 0.25 inch strand and a 144-count fiber optic cable on an existing pole line in Carroll, New Hampshire. -

Lincoln History

LINCOLN HISTORY 1764 Governor Benning Wentworth, the royal Governor of the Province of New Hampshire, granted 24,000 acres of land to James Avery of Norwich, Connecticut, and 64 of his relatives and friends. The Lincoln Charter was signed on January 31, 1764. Lincoln was named after Henry Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, 9th Earl of Lincoln, a Wentworth cousin. On the same day, Governor Wentworth signed a similar charter granting the adjoining town of Landaff to Avery and others. Avery and his associates made large investments in New Hampshire lands grants. However, none of the grantees ever lived in Lincoln let alone fulfill the conditions of the Charter which required that 5 of every 50 acres be cultivated within 5 years (1769). 1772 Governor John Wentworth declared the Lincoln Charter forfeited and re-granted Lincoln, along with most of Franconia, to Sir Francis Bernard and others. The name of this new township was Morristown, in honor of one of the grantees. 1774 Nathan Kinsman of Concord, N.H., a hatter and physician, bought 400 acres of land from William Broughton of Fairlee, VT, who had acquired the rights from one of the original grantees of Morristown. The cost was 60 pounds. 1782 Nathan Kinsman and his wife Mercy (Wheeler) moved to Lincoln, then called Morristown. He was joined by Nathan and Amos Wheeler and John and Thomas Hatch. According to the Federal Census of 1790, these 5 families, 22 inhabitants total, comprised the total population of Morristown. The area in which they settled was known as Lincoln Gore under the western slopes of the mountain to which Nathan gave his name. -

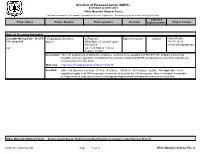

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 09/13/2018 [email protected] EIS Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) 01/01/2021 04:07 am MT Page 1 of 5 White Mountain National Forest Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Kilkenny Snowmobile Bridge - Recreation management Completed Actual: 11/02/2020 11/2020 Benjamin Farina Removal and Trail Relocation - Watershed management 603-536-6131 CE benjamin.farina@usda. -

Carroll NH Master Plan

Carroll New Hampshire Crossroads for Adventure Carroll New Hampshire Crossroads for Adventure Developed by the Carroll Master Plan Committee with assistance from the Carroll Conservation Commission and North Country Council Adopted by the Carroll Planning Board June 11, 2015 Photo credits: Tara Bamford, North Country Council Contents Page Introduction …………………………………………………… 1 The People ………………………………………………….. 3 Population Housing Income Housing Affordability Employment Property Taxes The Land ………………………………………………….. 17 The Future …………………………………………………. 37 Vision Survey Results Land Use Town Facilities APPENDIX A NRI Tables APPENDIX B NRI Maps APPENDIX C Survey Results Introduction The purpose of the Master Plan is to guide the future development of the town. More specifically, it will be used to guide the Planning Board to ensure it carries out its responsibilities in a manner that will best achieve the goals of the community. The Master Plan also represents the Planning Board’s recommendations to other town boards and committees and to the voters. The Master Plan is a policy document. It is not regulatory. The process of developing this Master Plan began with the appointment by the Planning Board, chaired by Donna Foster, of a Master Plan Committee. The Master Plan Committee was comprised of: George Brodeur, Chair Michael Hogan Evan Karpf Kenneth Mills North Country Council was hired to facilitate the public participation process and draft the plan document, with the exception of the natural resources section. A Natural Resource Inventory had recently been completed by the Carroll Conservation Commission; North Country Council Planning Coordinator Tara Bamford worked with the Commission to adapt this report to serve as the section entitled The Land. -

Visitor's Guide

NH AREA CODE IS 603 IS CODE AREA NH Resort Location Entertainment DR Destination Historic Arts & Arts Functions Rentals Onsite Breakfast Weddings / Weddings Vacation Shopping Entertainment Allowed Golf Fishing Live Pets Recreation Dining Pool Lodging Hiking Map Hiking Sports & & Sports Legend St., Route 117 - [email protected] [email protected] - 117 Route St., Main Main 823-5336 823-5336 Sugar Hill Historical Museum Historical Hill Sugar Route 117 - stmatthewsnh.org - 117 Route 823-8478 823-8478 Chapel Matthews St. sugarhillsampler.com sugarhillsampler.com 71 Sunset Hill Road Road Hill Sunset 71 - Sampler Hill Sugar 823-8478 Early Settlers & Family Museum at the the at Museum Family & Settlers Early SUGAR HILL HILL SUGAR 109 Main St. - NHMaplesyrup.com NHMaplesyrup.com - St. Main 109 - Sugarhouse 745-8371 Maple & Store General Fadden’s NORTH WOODSTOCK WOODSTOCK NORTH Ridge Road - frostplace.org frostplace.org - Road Ridge 158 823-5510 823-5510 The Frost Place Frost The Notch - oldmanofthemountainlegacyfund.org - Notch Exit 34C off I-93, Franconia Franconia I-93, off 34C Exit - Museum & Site Old Man of the Mountain Memorial Memorial Mountain the of Man Old 218-6703 Exit 34C off I-93, 9 Franconia Notch - skimuseum.org - Notch Franconia 9 I-93, off 34C Exit 823-7177 823-7177 New England Ski Museum Ski England New Jct. of Rtes. 18 & 117, Main St. - franconiaheritage.org - St. Main 117, & 18 Rtes. of Jct. Iron Furnace Interpretive Center Center Interpretive Furnace Iron 823-5000 Main Street - franconiaheritage.org franconiaheritage.org - Street Main 553 553 ea Heritage Museum Heritage ea 823-5000 823-5000 Franconia Ar Franconia FRANCONIA FRANCONIA 113 Glessner Road, Rte. -

Federal Lands Alternative: Transportation Systems Study

FINAL REPORT VOLUME III Federal Lands Alternative Transportation Systems Study Summary of Forest Service ATS Needs prepared for Federal Highway Administration Federal Transit Administration in association with U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. in association with Salish Kootenai College January 2004 Quality Assurance Statement The Federal Highway Administration provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average one hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, D.C. 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED January 2004 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Federal Lands Alternative Transportation Systems Study – Volume 3 – Summary of USDA DTFH61-98-D-00107, T045 Forest Service ATS Needs 6. AUTHOR(S) Daniel Krechmer, Lewis Grimm, Casey Frost, Iris Ortiz, Glen Weisbrod 8.