Bob Rintoul INTERVIEWER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1965-66 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1965-66 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Toe Blake 2 Gump Worsley 3 Jacques Laperriere 4 Jean Guy Talbot 5 Ted Harris 6 Jean Beliveau 7 Dick Duff 8 Claude Provost 9 Red Berenson 10 John Ferguson 11 Punch Imlach 12 Terry Sawchuk 13 Bob Baun 14 Kent Douglas 15 Red Kelly 16 Jim Pappin 17 Dave Keon 18 Bob Pulford 19 George Armstrong 20 Orland Kurtenbach 21 Ed Giacomin 22 Harry Howell 23 Rod Seiling 24 Mike McMahon 25 Jean Ratelle 26 Doug Robinson 27 Vic Hadfield 28 Garry Peters 29 Don Marshall 30 Bill Hicke 31 Gerry Cheevers 32 Leo Boivin 33 Albert Langlois 34 Murray Oliver 35 Tom Williams 36 Ron Schock 37 Ed Westfall 38 Gary Dornhoefer 39 Bob Dillabough 40 Paul Popeil 41 Sid Abel 42 Roger Crozier Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Doug Barkley 44 Bill Gadsby 45 Bryan Watson 46 Bob McCord 47 Alex Delvecchio 48 Andy Bathgate 49 Norm Ullman 50 Ab McDonald 51 Paul Henderson 52 Pit Martin 53 Billy Harris 54 Billy Reay 55 Glenn Hall 56 Pierre Pilote 57 Al MacNeil 58 Camille Henry 59 Bobby Hull 60 Stan Mikita 61 Ken Wharram 62 Bill Hay 63 Fred Stanfield 64 Dennis Hull 65 Ken Hodge 66 Checklist 1-66 67 Charlie Hodge 68 Terry Harper 69 J.C Tremblay 70 Bobby Rousseau 71 Henri Richard 72 Dave Balon 73 Ralph Backstrom 74 Jim Roberts 75 Claude LaRose 76 Yvan Cournoyer (misspelled as Yvon on card) 77 Johnny Bower 78 Carl Brewer 79 Tim Horton 80 Marcel Pronovost 81 Frank Mahovlich 82 Ron Ellis 83 Larry Jeffrey 84 Pete Stemkowski 85 Eddie Joyal 86 Mike Walton 87 George Sullivan 88 Don Simmons 89 Jim Neilson (misspelled as Nielson on card) -

1965-66 Toronto Maple Leafs 1965-66 Detroit Red Wings 1965

1965-66 Montreal Canadiens 1965-66 Chicago Blackhawks W L T W L T 41 21 8 OFF 3.41 37 25 8 OFF 3.43 DEF 2.47 DEF 2.67 PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM Bobby Rousseau RW 70 30 48 78 20 13 12 2 C Bobby Hull LW 65 54 43 97 70 23 11 9 A Jean Beliveau C 67 29 48 77 50 25 24 8 B Stan Mikita F 68 30 48 78 58 35 23 16 B Henri Richard F 62 22 39 61 47 34 34 13 B Phil Esposito C 69 27 26 53 49 46 30 22 B Claude Provost RW 70 19 36 55 38 42 44 18 B Bill Hay C 68 20 31 51 20 55 38 24 C Gilles Tremblay LW 70 27 21 48 24 53 49 20 B Doug Mohns F 70 22 27 49 63 64 45 32 B Dick Duff LW 63 21 24 45 78 62 55 29 A Chico Maki RW 68 17 31 48 41 71 53 37 B Ralph Backstrom C 67 22 20 42 10 71 60 30 C Ken Wharram C 69 26 17 43 28 82 57 41 B J.C. Tremblay D 59 6 29 35 8 74 67 31 C Eric Nesterenko C 67 15 25 40 58 88 63 48 B Claude Larose RW 64 15 18 33 67 80 72 39 A Pierre Pilote D 51 2 34 36 60 89 72 55 B Jacques Laperriere D 57 6 25 31 85 82 78 49 A Pat Stapleton D 55 4 30 34 52 91 80 62 B Yvan Cournoyer F 65 18 11 29 8 90 81 49 C Ken Hodge RW 63 6 17 23 47 93 84 67 B John Ferguson RW 65 11 14 25 153 95 85 67 A Doug Jarrett D 66 4 12 16 71 95 87 76 A Jean-Guy Talbot D 59 1 14 15 50 - 88 73 B Matt Ravlich D 62 0 16 16 78 - 91 86 A Ted Harris D 53 0 13 13 87 - 92 82 A Lou Angotti (fr NYR) RW 30 4 10 14 12 97 94 87 C Terry Harper D 69 1 11 12 91 - 94 93 A Len Lunde LW 24 4 7 11 4 99 96 88 C Jim Roberts D 70 5 5 10 20 97 96 95 C Elmer Vasko D 56 1 7 8 44 - 97 93 B Dave Balon LW 45 3 7 10 24 98 97 98 B Dennis Hull LW 25 1 5 6 6 -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

PLAYOFF HISTORY and RECORDS RANGERS PLAYOFF Results YEAR-BY-YEAR RANGERS PLAYOFF Results YEAR-BY-YEAR

PLAYOFF HISTORY AnD RECORDS RANGERS PLAYOFF RESuLTS YEAR-BY-YEAR RANGERS PLAYOFF RESuLTS YEAR-BY-YEAR SERIES RECORDS VERSUS OTHER CLUBS Year Series Opponent W-L-T GF/GA Year Series Opponent W-L-T GF/GA YEAR SERIES WINNER W L T GF GA YEAR SERIES WINNER W L T GF GA 1926-27 SF Boston 0-1-1 1/3 1974-75 PRE Islanders 1-2 13/10 1927-28 QF Pittsburgh 1-1-0 6/4 1977-78 PRE Buffalo 1-2 6/11 VS. ATLANTA THRASHERS VS. NEW YORK ISLANDERS 2007 Conf. Qtrfinals RANGERS 4 0 0 17 6 1975 Preliminaries Islanders 1 2 0 13 10 SF Boston 1-0-1 5/2 1978-79 PRE Los Angeles 2-0 9/2 Series Record: 1-0 Total 4 0 0 17 6 1979 Semifinals RANGERS 4 2 0 18 13 1981 Semifinals Islanders 0 4 0 8 22 F Maroons 3-2-0 5/6 QF Philadelphia 4-1 28/8 VS. Boston BRUINS 1982 Division Finals Islanders 2 4 0 20 27 1928-29 QF Americans 1-0-1 1/0 SF Islanders 4-2 18/13 1927 Semifinals Bruins 0 1 1 1 3 1983 Division Finals Islanders 2 4 0 15 28 SF Toronto 2-0-0 3/1 F Montreal 1-4 11/19 1928 Semifinals RANGERS 1 0 1 5 2 1984 Div. Semifinals Islanders 2 3 0 14 13 1929 Finals Bruins 0 2 0 1 4 1990 Div. Semifinals RANGERS 4 1 0 22 13 F Boston 0-2-0 1/4 1979-80 PRE Atlanta 3-1 14/8 1939 Semifinals Bruins 3 4 0 12 14 1994 Conf. -

Summer Highlights 3D in the Making Recent Acquisitions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL > SUMMER HIGHLIGHTS 3D IN THE MAKING RECENT ACQUISITIONS FALL 2012 Letter from the Chairman & CEO On June 26, 2012 our esteemed Selection Committee met and Friday, November 9, 2012 deliberated on candidates for The public launch of the Hockey Hall of Fame’s newest feature film, Stanley’s Game Seven (3D). Ben Welland/HHOF-IIHF Images Ben Welland/HHOF-IIHF the 2012 Induction. We are very pleased to congratulate hockey’s newest leg- 7:00pm ends, Pavel Bure, Adam Oates, Joe Sakic and Mats Hockey Hall of Fame Game Sundin, on their upcoming Induction set for Monday, Air Canada Centre New Jersey Devils vs. Toronto Maple Leafs November 12th. This year’s Inductee announcement was broadcast live for the second year on TSN, and for the first time ever, the Official Hockey Hall of Fame Saturday, November 10, 2012 Game (Devils vs. Leafs) is scheduled for TSN broadcast A special 2012 Limited Edition Inductee Poster will be distributed to guests upon entry to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The first 500 patrons will receive a poster autographed by on Friday, November 9th. the 2012 Inductees. We also congratulate the Los Angeles Kings on 1:30 – 4:00pm 1972 Summit Series Fan Forums becoming the Stanley Cup Champions for the 2011-2012 A series of Q & A sessions, hosted by Ron Ellis, celebrating the 40th anniversary of season. It seems fitting that since the Cup has “gone the historic tournament. Hollywood” so has its home - the Hockey Hall of Fame. We have teamed up with Network Entertainment Inc. -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

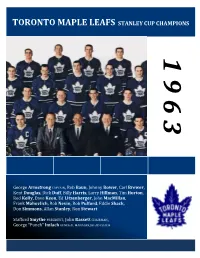

TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 3 George Armstrong CAPTAIN, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Carl Brewer, Kent Douglas, Dick Duff, Billy Harris, Larry Hillman, Tim Horton, Red Kelly, Dave Keon, Ed Litzenberger, John MacMillan, Frank Mahovlich, Bob Nevin, Bob Pulford, Eddie Shack, Don Simmons, Allan Stanley, Ron Stewart Stafford Smythe PRESIDENT, John Bassett CHAIRMAN, George “Punch” Imlach GENERAL MANAGER/HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1963 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS 82 v. MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 79 GM PUNCH IMLACH, HC PUNCH IMLACH v. GM FRANK J. SELKE, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE MAPLE LEAFS WIN SERIES IN 5 Tuesday, March 26 Thursday, March 28 MONTREAL 1 @ TORONTO 3 MONTREAL 2 @ TORONTO 3 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. TORONTO, Bob Pulford 1 (Allan Stanley, Johnny Bower) 3:30 1. MONTREAL, Jean Béliveau 2 (unassisted) 6:07 2. TORONTO, George Armstrong 2 (unassisted) 6:54 Penalties – Stanley T 8:42, Horton T 9:17, Laperrière M 10:05, Harper M Pulford T 11:05, Harper M 18:16 Penalties – Mahovlich T 2:45, Gauthier M 14:54 SECOND PERIOD 2. -

42!$)4)/. Tradition Trad T Tra Rad R a Ad D Itio Iti I Ti Tio O N

42!$)4)/. TRADITION TRAD T TRA RAD R A AD D ITIO ITI I TI TIO O N CHICAGOBLACKHAWKS.COMCCHICHCHICHICHHIICICAGOBAGAGOAGGOGOBOOBBLLACLACKLAACACKACCKKHAWKHAHAWHAWKAWAWKWKSCOSSCS.COS.S.C.CCOCOM 23723737 2%4)2%$37%!4%23 TRADITION 3%!3/.37)4(",!#+(!7+3: 22 (1958-1980)9880)0 37%!4%22%4)2%$ October 19, 1980 at Chicagoaggo Stadium.StS adadiuum.m. ",!#+(!7+3#!2%%2()'(,)'(43 Playedyede hishiss entireenttirre 22-year222 -yyeae r careercacareeere withwitith thethhe Blackhawks ... Led the Blackhawks to the 1961 Stanleyey CupCuC p andana d pacedpacec d thetht e teamtet amm inin scoringscs oro inng throughout the playoffs ... Four-time Art Ross Trophy winner (1964, 1965, 1967 & 1968) ... Two-time Hart Trophy Winner (1967 & 1968) ... Two-time Lady Bing Trophy winner (1967 & 1968) ... Lester Patrick Trophy winner (1976) ... Six-time First Team All-Star (1962, 1963, 1964, 1966, 1967 & 1968) ... Only player in NHL history to win the Art Ross, Hart, and Lady Bing Trophies in the same season (1966-67 & 1967-68) ... Two-Time Second Team All-Star (1965 & 1970 ... Hawks all-time assists leader (926) ... Hawks all-time points leader (1,467) ... Second to Bobby Hull in goals (541) ... Blackhawks’ leader in games played (1,394) ... Hockey Hall of Fame inductee (1983) ... Blackhawks’ captain in 1975-76 & 1976-77 ... First Czechoslovakian-born player in the NHL ... Member of the famous “Scooter Line” with Ken Wharram and Ab McDonald, and later Doug Mohns ... Named a Blackhawks Ambassador in a ceremony with Bobby Hull at the United Center on March 7, 2008. 34/3( 238 2009-10 CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS MEDIA GUIDE 2%4)2%$37%!4%23 TRADITION TRAD ITIO N 3%!3/.37)4(",!#+(!7+33%!3/3 ..33 7)7)4(( ",!#+#+(!7! +3 155 (1957-1972)(1919577-1-1979722)) 37%!4%22%4)2%$37%!4%22%4)2%$ DecemberDecec mbm ere 18,18,8 1983198983 atat ChicagoChih cacagoo Stadium.Staadid umm. -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

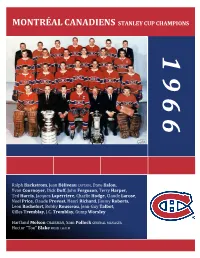

MONTRÉAL CANADIENS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 6 Ralph Backstrom, Jean Béliveau CAPTAIN, Dave Balon, Yvan Cournoyer, Dick Duff, John Ferguson, Terry Harper, Ted Harris, Jacques Laperriere, Charlie Hodge, Claude Larose, Noel Price, Claude Provost, Henri Richard, Jimmy Roberts, Leon Rochefort, Bobby Rousseau, Jean-Guy Talbot, Gilles Tremblay, J.C. Tremblay, Gump Worsley Hartland Molson CHAIRMAN, Sam Pollock GENERAL MANAGER Hector “Toe” Blake HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1966 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 90 v. 3 TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS 79 GM SAM POLLOCK, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE v. GM PUNCH IMLACH, HC PUNCH IMLACH CANADIENS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 7 Saturday, April 9 TORONTO 3 @ MONTREAL 4 TORONTO 0 @ MONTREAL 2 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. TORONTO, Eddie Shack 1 (Bob Pulford, Red Kelly) 2:12 NO SCORING 2. MONTREAL, J.C. Tremblay 1 (unassisted) 12:06 PPG 3. TORONTO, Frank Mahovlich 1 (George Armstrong, Larry Hillman) 18:06 PPG Penalties – Horton T 0:34, Larose M 3:55, Baun T Pulford T (10-minute misconduct) 7:33, Stemkowski T 10:11, Horton T Hillman T Harris M J.C. -

Maple Leafs Centennial Exhibit Oilers Ice District Recent Acquistions

HOCKEY HALL of FAME NEWS and EVENTS JOURNAL MAPLE LEAFS CENTENNIAL EXHIBIT OILERS ICE DISTRICT RECENT ACQUISTIONS FALL 2016 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD Dear Teammates: Kudos to the NHL, the NHLPA and especially the world’s best players for Friday, November 11, 2016 Hockey Hall of Fame a highly entertaining and successful 2:00pm World Cup of Hockey! Kudos to the 2016 World Cup of Hockey Induction Media Conference This event will include the ring presentations to the 2016 Inductees. champions Team Canada! Kudos to the Edmonton Oilers on the opening of their spectacular new arena and surrounding 7:00pm “Ice District” development! And kudos to Toronto Blue Jays fans Hockey Hall of Fame Game across Canada for making their pilgrimage to the Hall this Philadelphia Flyers vs. Toronto Maple Leafs summer! Air Canada Centre While special events and other external forces are among the key factors that contribute to the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Saturday, November 12, 2016 continued success, the prospects for future growth and 1:30pm – 2:30pm development through strategic partnerships remains a high Scotiabank Inductee Fan Forum Q & A session with the 2016 Inductees. priority. Best ever consolidated operating results in each of the past two fiscal years has enabled the Hall to fully retire its long term debt obligations to the NHL dating back to the 1993 SuNday, November 13, 2016 relocation and expansion from the CNE Grounds to Brookfield Place. Forging a renewed cooperation with the NHL, the Hall’s 12:00pm – 1:00pm Legends Autograph Signing cornerstone founding benefactor, is in the works as the NHL Honoured Members Eric Lindros and Borje Salming will be signing a limited-edition Centennial Celebrations are on the horizon. -

PLASTIC Forth in A, Eutement Laaued at Hie Members of Manchester Em Lez Issue, Mage Sale at the Oommunity Y Them

■r'<. MONDAY, APRIL 22, 1987 Average JDaily. Net Press Run PAGE B OURTEEiJ Fer the Week Ended iiarirhfBtrr liJPttittg April to, 1857 ly..^ w all who are spiritually dead The'Miegulgrly scheduled meet Christ. Jia» la to Interpret ;4raglc here grave. The risen Christ affirms the or I dijnBg the risen Christ gives 12,579 ing of Stmiet Circle, Past Noble PapUst Minister experience. As the-saddened pair r a ^ . ' . About w-alked the Ehtamaus road thelf answer that the Ultimate reality popver todiay. T am Ui,e reauTreC' Member of the Audit Grands, slaieo^for tonight has Bureau of OIroalation been pbatponed Hn order that a Gives Sermoii on stranger-compantoh pointed out. of thls\Mlverse is the power of (t^and the life, all wrhb believe in degree rehearsal may be held. ‘Was It • not. necessary that the God. Said, the Lord, Thave. conme mei and truly follow me>shalVlive,'''1 ! ■ Yt'PR ROUND illR CONDIIIONING T ea^l* Chapter,' No. 53, Order they may nave it more abundant- quilted the Revj Mr. Neubert in of the BMtem Star, will meet ‘Power of Christ’ Christ should suffer these things The Immaculate \ Conception 'and enter Into Hla glory?' In hu they may htave it more abundant- coa elusion. 'WMneMtey evening'et, 8 o'clock Jn >VOL\LXXVI, NO. 178 (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, fcONN., TUESDAY, AP;BIL 23, 1957 the Itoeonlc ‘I'emple. The Imelnwe Mothers Circle will m e^ Wednes man affairs no great gain has ever LONG EXPERIENCE day night at 8 o’clock at the home "Thou'^h. -

2016-17 Media Guide

2016-17 MEDIA GUIDE 1 Media Guide Cover 8 Final Cover to print.indd 1 9/2/16 1:45 PM 2 3 ONCE A RANGER Remembering Andy Bathgate Andy Bathgate, one of the greatest players to ever wear a Rangers uniform, passed away on February 26, 2016. He was 83 years old. Bathgate, whose legendary accomplishments with the Rangers on the ice were only rivaled by his class and dignity off the ice, was the face of the Blueshirts during his 12 seasons in New York. At the time of his departure from the Rangers, Bathgate was the franchise’s all-time leader in goals, assists, and points. An eight-time NHL All-Star, Bathgate won the Hart Trophy as the NHL’s Most Valuable Player in 1958-59 and he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1978. On February 22, 2009, Bathgate was bestowed with the highest honor a Rangers player can receive, as his No. 9 jersey was retired and raised to the rafters at Madison Square Garden. “The New York Rangers and the “Andy set the bar for what hockey world lost a beloved it means to be a Ranger. He and cherished member of its was a true innovator of the community with the passing of game and my idol. As a young our Legendary Blueshirt, Andy Bathgate. Andy’s Hall of Fame player, I was fortunate to have career and many tremendous the opportunity to play with accomplishments place him him and learn from him. He among the greatest players who was class personified, on and have ever worn a Rangers jersey. -

Weekend Magazine Collection Finding Aid

Weekend Magazine Collection Finding Aid Explanation of the series: The groups identified in the trakker circulation system were created to imitate the manner the Weekend Magazine stored its photo library. The collection is essentially chronological, following the numbering system of the dockets. To find the most material from a particular date, it would be advisable to look into multiple series, as the same story is sometimes repeated in different series. Each original docket is stamped with the format (IE “colour” and/or “safety”) indicating whether material can be found elsewhere. However, as the note for Group 2 indicates, much of the safety material is simply a copy of the original colour item. Group 1 consists of small original dockets that originally held one black and white negative that was used in publication (and on occasion a few “outs”). Group 1 material was photographs that were originally taken on black and white film, in various formats and sizes. It includes nitrate, safety and a very small quantity of diacetate. The first 10 pages of this finding aid are also located, with more contextual information, in the other Weekend Magazine finding aid, which concentrates on The Standard. Group 2 consists of photographs that were originally taken on colour transparency film. The series also includes black and white material as well: these images are all copies of what was originally a colour transparency. The magazine’s policy was to make b&w reproductions of photographs taken by freelancers and it appears that many original colour items taken by staff were also copied onto black and white (mainly safety) stock.