2 A.M., with a Package

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maritime Trade of Ancient Tamils with the East and West Thespecial Reference to Arikamedu

Maritime Trade of Ancient Tamils with the East and West theSpecial reference to Arikamedu J. Sounodararajan, Dept. of AH& Archaeology, University of Madras, Chepauk, Chennai – 600 005. India. Mail. ID: [email protected] Mobile No: 09444891589 Arikamedu and Rome –Ancient Trade contact The place which is 5 kmsaway from Puduchery is known as,” Arikamedu”. It is located on the banks of the river Ariyankuppam near Kakaiyanthoppu, enrouteAriyankuppam and Virampattinam, which is 20 feet in height in the form of a mound. Today this placeexists as clam and humble garden area. The very same place was once flourished as a multi – national port city. During ancient period, this place was inhabited by the people who were hailed from different countries and they spoke many different languages. On the basis of trade and commerce they mingled with one another. In the beginning years of the 18th century very few Christian Fathers lived in Puducherry. They instituted missionaries at Arikamedu and did their religious services. They never knew about the ancient podukal’s history or specialty. Later, in 1769 A D, Le Gentil, a French astronomical expert came to Puducherry for his research. He personally visited the Veerampattinam and Arikamedu areas. In his travel accounts he mentions about an Arukansilai(Buddha Statue) which was discovered by him. By this finding the place of Arikamedu won 1st and became noticeable by the historians(researchers). Later in the early years of the 20th century 1937 AD, JoyveaeDubraille, a physics professor, Puduvai-French college visited Arikamedu many times to see the ruins of the Christian Misisionary. -

Containers January 2017 A) Origin Pre-Shipment Sampling

ECOM AGROINDUSTRIAL CORP. LTD. Best Practice Pre-shipment Instructions – Containers January 2017 A) Origin pre-shipment sampling: All testing to be carried out by appropriately qualified persons designated by ECOM at Seller’s cost. Equipment to be used for moisture testing is the ‘Aqua Boy’ for individual bags with a composite sample from each 25 MT lot to be tested using ‘Dickey John’. The moisture meters must be calibrated to “Tropical Conditions” and certified annually. 100% of bags must be tested for moisture levels by Aqua Boy probe test from every 25 MT lot immediately prior to stuffing into export container. If found to be over 7% moisture the bags are to be rejected. No bags having over 7% moisture can be loaded. (Please note that probe tests are considered to read 1% lower that cup tests so are less reliable) The party carrying out the testing will record and submit reports (format to be agreed by ECOM) of the results on a weekly basis to the Rekerdres claims manager – [email protected] B) Container inspections: External: There are to be minimum dents, no holes or splits. If present - reject. Look for International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) code labels and if present - reject the container. Look also for any indication of labels having been present / areas painted over on the sides of containers and if suspected – reject. Internal: No rust, foreign odours, foreign substances or dirty floors and if present - reject. Floor moisture levels to be checked in 9 areas throughout the container and if found to be above 12% at any testing point - reject. -

Answer Key the Safe Food Handler, Page 4-6

HACCP In Your School Answer Key The Safe Food Handler, Page 4-6 Can They Handle It? - For each situation, should the worker be working? No Sue has developed a sore throat with fever since coming to work. Sore throat with a fever is one of the five symptoms of foodborne illness and so the worker should be excluded from working in the establishment. Yes Cindy has itchy eyes and a runny nose. Itchy eyes and a runny nose are not symptoms of foodborne illness so Cindy would be able to work. However, each time Cindy wipes her eyes or her nose, she must properly wash her hands for 20 seconds using warm water, soap, and drying with a paper towel. No Tom vomited several times before coming to work. Tom cannot work because vomiting is a symptom of foodborne illness. Tom can return to work once the vomiting has stopped. If a medical professional determines that there is another reason for Tom’s vomiting that is not related to foodborne illness, Tom can work as long as he presents proper medical documentation. If the worker was a pregnant female, the vomiting would be determined to be due to morning sickness and so she could work. After each episode of vomiting, hands must be properly washed for 20 seconds using warm water, soap, and drying with a paper towel. No Juanita has had a sore throat for several days but still came to work today. Juanita cannot work because she has had a sore throat for several days and so the cause of the sore throat might be an infection. -

Wentzville R-Iv School District

WENTZVILLE R-IV SCHOOL DISTRICT 2021-2022 SCHOOL SUPPLY LIST Grades 4-6 3/31/21 GRADE 4 GRADE 5 GRADE 6 1 Box markers 4 Composition notebooks 1 Pair scissors (adult size) 1 Pkg. colored pencils* 3 Boxes facial tissue (girls only)* 48 #2 pencils 3 Pkgs. black dry erase markers 3 Pkgs. #2 yellow pencils - sharpened 1 Bottle white glue 3 Boxes facial tissue 1 Pkg. loose leaf paper (wide-rule) 1 Pkg. dry erase markers (4 pack)* 1 Pair scissors 1 Box markers 5 Glue sticks* 3 Glue sticks 1 Box colored pencils 1 Pkg. colored pencils* 3 Pkgs. #2 yellow pencils (24 ct.) sharpened 1 Box 24 ct. crayons 2 Highlighters* 1 1 ½” 3-ring binder (clear view front 1 Pair scissors (adult size) 1 Basic calculator w/pockets) 1 Pkg. of 3 glue sticks 1 Computer mouse 6 Two-pocket plastic/vinyl folders, 3-hole 6 Spiral notebooks (red, green, blue, yellow, 1 Zipper binder punched, solid colors orange and purple) 1 Roll paper towels 4 Spiral notebooks, 3-hole punched, solid 6 Two-pocket plastic/vinyl folders with prongs 2 Boxes facial tissue* colors (red, green, blue, yellow, orange and purple) 1 Pkg. 3”x5” index cards 1 Pkg. loose leaf paper, wide-rule 2 Pkgs. dry erase markers (4 or more per 1 Zipper pencil pouch for binder 3 Pkgs. sticky notes (3”x3”) pack) 1 Pkg. sticky notes (3”x3”) 1 Pink pencil eraser 1 1 ½” 3-ring binder (clear view front 1 Roll transparent tape 1 Roll paper towels w/pockets) 5 Composition notebooks 1 Box sandwich size zipper storage bags 6 Pkgs. -

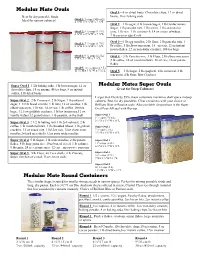

Modular Mates

Modular Mate Ovals Oval 1—8 oz dried fruits, Chocolate chips, 12 oz dried Best for dry pourable foods. beans, 16 oz baking soda Oval 1: 2-cups (500 mL) Ideal for narrow cabinets! 2 ¼"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L Oval 2—1 lb sugar, 2 lb brown Sugar, 1 lb Confectioners Sugar, 1 lb pancake mix, 1 lb raisins, 1 lb cornmeal or Oval 2: 4 ¾-cups (1.1 L) grits, 1 lb rice, 1 lb cornstarch, 18 oz cream of wheat, 4 ½"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L 1 lb cocoa or quick mix Oval 3—1 lb egg noodles, 2 lb flour, 2 lb pancake mix, 1 Oval 3: 7 ¼-cups (1.7 L) 6 ¾"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L lb coffee, 1 lb elbow macaroni, 18 oz oats, 12 oz instant potato flakes, 22 oz non-dairy creamer, 100 tea bags Oval 4: 9 ¾-cups (2.3 L) Oval 4 - 3 lb Pancake mix, 3 lb Flour, 2 lb elbow macaroni, 9"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L 2 lb coffee, 10 oz marshmallows, 60 oz rice, 16 oz potato flakes Oval 5: 12 ¼-cups (2.9 L) 11 ¼"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L Oval 5— 5 lb Sugar, 5 lb spaghetti, 4 lb cornmeal, 3 lb macaroni, 4 lb flour, Ritz Crackers Super Oval 1 1 Lb baking soda, 1 lb brown sugar, 12 oz Modular Mates Super Ovals chocolate chips, 15 oz raisins, 40 tea bags, 8 oz instant Great for Deep Cabinets! coffee, 1 lb dried beans Larger than Ovals by 55%, these containers maximize shelf space in deep Super Oval 2 2 lb Cornmeal, 2 lb Sugar, 1 lb powered cabinets. -

2021 Concessions Catalog

MORE THAN A CUP.CUP PAGE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS About Us About Us Page 2 In-Mold Labeled IML Cups Pages 3 - 4 IMLS Cups Pages 5 - 6 Double Wall Cup Pages 7 - 8 Buckets Pages 9 - 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Plastic Film Buckets Page 11 - 12 Boxes Pages 13 - 14 Lenticular 3D Lenticular 3D Cups Page 15 - 16 Heat Transferred Mason Jars Pages 17 - 18 Shakers & Carafes Pages 19 - 20 Dry Oset Printed Traditional Cups Page 21 - 22 Fluted Cups Page 23 - 24 Disposable Cups Page 25 - 26 Accessories Accessories Page 27 Sipper Lids Page 28 Added Value Specialty Options Page 29 Refill Programs Page 30 Augmented Reality Page 31 Why Reusable? Page 32 GENERAL GRAPHICS 800.999.5518 800.999.5518 [email protected] [email protected] JOE BLANDO MIKE JACOB Vice President of Sales National Sales Manager of Concessions 920.527.8326 785.749.1213 [email protected] [email protected] Download templates & upload artwork at churchillcontainer.com Call us at 800.999.5518 Connect with us ABOUT US Churchill Container designs and produces rigid plastic cups and containers for clients who value branded package design as a marketing tool. Since 1980, we’ve been helping promote brands and increase revenue with programs designed to drive repeat business. Our killer in-house art department is the best in the business and our single Midwest production facility enables us to provide consistent quality control and efficient tracking of orders. We offer an incredible array of options to raise the perceived value of any food or beverage product. -

The Dating of Arikamedu and Its Bearing on the Archaeology of Early Historical South India

The Dating of Arikamedu and its Bearing on the Archaeology of Early Historical South India †Vimala Begley* I As a result of the excavations conducted by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in 1945 (Wheeler et al. 1946), Arikamedu has come to be regarded as the most crucial site for dating of the archaeological finds at early historical sites in South India. The unique character of Arikamedu for dating is primarily due to the discovery of Mediterranean imports in systematic excavations undertaken there by several archaeologists: Wheeler in 1945 (Wheeler et al. 1946), L-M. Casal in 1947-50 (Casal 1949; Casal and Casal 1956) and more recently, in 1990-92 by myself (Begley 1993; Begley et al. 1996).1 Today, some fifty years after Wheeler's excavations, Arikamedu is still the only site in peninsular India where absolute dates, as well as a relative chronology for its ancient settlement can be attempted. Accordingly, more precise dates for some of the Brahmi and Tamil-Brahmi graffiti on pottery sherds can also be proposed. However, it is not my intention here to discuss the material from all the relevant early historical sites, for the number is large and frequently the material is not published in detail. Only two sites, Karaikadu and Alagankulam, have been chosen for comparison here, because I was able to study some of the material from there and did not have to depend upon 2 published sources alone. * [Note (by I. Mahadevan): When I was completing my book on Tamil-Brahmi cave inscriptions, I had also planned a companion volume devoted to the study of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions on pottery and other inscribed objects like coins and seals. -

Sweet Spreads–Butters, Jellies, Jams, Conserves, Marmalades and Preserves–Add Zest to Meals

Sweet spreads–butters, jellies, jams, conserves, marmalades and preserves–add zest to meals. They can be made from fruit that is not completely suitable for canning or freezing. All contain the four essential ingredients needed to make a jellied fruit product–fruit, pectin, acid and sugar. They differ, however, depending upon fruit used, proportion of different ingredients, method of preparation and density of the fruit pulp. Jelly is made from fruit juice and the end product is clear and firm enough to hold its shape when removed from the container. Jam is made from crushed or ground fruit. The end product is less firm than jelly, but still holds its shape. This circular deals with the basics of making jellies and jams, without adding pectin. Recipes for making different spreads can be found in other food preservation cookbooks. Recipes for using added pectin can be found on the pectin package insert sheets. Essential Ingredients Fruit furnishes the flavor and part of the needed pectin and acid. Some irregular and imperfect fruit can be used. Do not use spoiled, moldy or stale fruit. Pectin is the actual gelling substance. The amount of pectin found naturally in fruits depends upon the kind of fruit and degree of ripeness. Underripe fruits have more pectin; as fruit ripens, the pectin changes to a non-gelling form. Usually using 1⁄4 underripe fruit to 3⁄4 fully-ripe fruit makes the best product. Cooking brings out the pectin, but cooking too long destroys it. High pectin fruits are apples, crabapples, quinces, red currants, gooseberries, Eastern Concord grapes, plums and cranberries. -

Syrup Quality Guidelines

Syrup Quality Guidelines Rotate your syrup stock. Always use the oldest syrup first to maintain freshness. Remember FEFO... First to Enjoy By, First Out! Syrup should be used before “Enjoy-By” date. Each syrup container is stamped with a date code indicating the “Enjoy- By” date. The date code is on a label affixed to the box. USA Sample Label SAP Material Number Resource Number SAP Batch Number Enjoy-By Date (75 Days*) *Enjoy-By Dates 75, 90, or 120 days CANADA 20L or 10L BIB size (5 gal) (2.5 gal) Product (Coca-Cola®) “Enjoy-By” Date Producing Facility Day Code Time of Production (JN1311) (BN) (“E”=Friday) (05:35) 2011031802.Syrup Quality.indd 1 5/31/2011 12:57:38 PM Change the BIB’s properly. See Valves of Gold Dispenser Cleaning/Sanitizing Instructions for details. How to Change a Bag-in-Box Step 1. Wash hands with soap Step 2. Unscrew the syrup Step 3. Open the flap of the and water. line connector and remove new box by hitting it sharply the empty box. with your palm. DO NOT use a sharp instrument. Step 4. Pull the bag connec- Step 5. Soak connectors in Step 6. Reconnect to the tor through the opening and chlorine based sanitizer solu- correct Bag-in-Box. Tighten remove the plastic dust cap. tion for 1 minute. until the connectors are fully engaged. Store Syrups at the Proper Temperature. Syrups must be stored in a cool indoor location. Syrups should not be stored in refrigerated coolers. Syrup storage temperatures should be between 40˚F to 77˚F (4.4˚C to 25˚C), except for Nestea® and Gold Peak® products, which should not be stored below 50˚F (10˚C). -

0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP in MINI-BAG Plus Container VIAFLEX Plastic Container

0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP in MINI-BAG Plus Container VIAFLEX Plastic Container DESCRIPTION 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP in the MINI-BAG Plus Container is a sterile, nonpyrogenic solution for intravenous administration after admixture with a single dose powdered drug. It contains no antimicrobial agents. The nominal pH is 5.0 (4.5 to 7.0). Each 100 mL contains 900 mg of Sodium Chloride, USP (NaCl). The osmolarity is 308 mOsmol/L (calculated). It contains 154 mEq/L sodium and 154 mEq/L chloride. The MINI-BAG Plus Container is a standard diluent container with an integral drug vial adaptor. It allows for drug admixture after connection to a single dose powdered drug vial having a 20 mm closure. A breakaway seal in the tube between the vial adaptor and the container is broken to allow transfer of the diluent into the vial and reconstitution of the drug. The reconstituted drug is then transferred from the vial into the container diluent and mixed to result in an admixture for delivery to the patient. The VIAFLEX Plastic Container is fabricated from a specially formulated polyvinyl chloride (PL 146 Plastic). Exposure to temperatures above 25°C/77°F during transport and storage will lead to minor losses in moisture content. Higher temperatures lead to greater losses. It is unlikely that these minor losses will lead to clinically significant changes within the expiration period. The amount of water that can permeate from inside the container into the overwrap is insufficient to affect the solution significantly. Solutions in contact with the plastic container can leach out certain chemical components from the plastic in very small amounts. -

Kindergarten • 1 Backpack – NO WHEELS • 2 Pkg of 4 Fat Pencils • 2

Kindergarten 1 backpack – NO WHEELS 2 pkg of 4 fat pencils 2 pkg of #2 Pencils 6 pkgs 24 Crayola Crayons 12 glue sticks Plastic Pencil box (big enough for crayons to fit in) 4 PLASTIC pocket folders with 3 prongs 4 pkg of 4 (or more) Expo Dry Erase Markers (BLACK Only) 1 pair of scissors 1 pink eraser 2 box of Kleenex 1 roll of paper towels 1 baby wipes container or refill 1 pair of headphones (for use in the computer room, can be bought at Dollar Tree or Five Below) 1 clipboard labeled with child’s name 1 clear plastic show box with white lid – labeled with child’s name 4 pack of Play-Doh Boys - Avery Labels with 80 on the sheet, 1 box sandwich size Ziplocs, 1 container of hand sanitizer Girls - Avery Labels with 30 on the sheet, 1 box quart size Ziplocs, 1 container Lysol wipes $5.00 snack money each quarter First Grade (Community supplies-only label items indicated) 8 BLACK fat dry erase markers 48 #2 pencils (sharpened) 4 boxes 24-count crayons pencil top erasers 8 glue sticks 1 pair of scissors (labeled w/child's name) 8 wide ruled composition notebooks (NOT spiral) 1 set earbuds (labeled w/ child's name) 1 plastic pencil box (labeled w/ child's name) 1 clipboard (labeled w/ child's name) 1 clear plastic shoe box w/white lid (labeled w/ child's name) 2 boxes tissues 4plastic folders w/ 3 prongs (1 each - green, red, blue, yellow) Baby Wipes Ziploc bags 1 rolls paper towels Paper Plates $5 snack money each quarter Second Grade (Community supplies-do not label with names) 1 backpack (NO WHEELS) -

Packaging of Wheat Flour Packaging Introduction

PACKAGING OF WHEAT FLOUR PACKAGING INTRODUCTION Shelf Life of Product: • Flour infestation is a common problem that both traders and flour millers face. • Maintaining the consistency of the grain and its flour is a difficult task. • With due treatment & managed conditioned climate, flour can be stored without any signs of damage for up to 6 months. • In the open condition, it gets infested within 2 months, affecting flour's shelf life. 2 INTRODUCTION Milled Flour is infested for a variety of reasons- The moisture content of the Wheat flour Storage Conditions Storage –Temperature & Humidity Cross Contamination Unhygienic Conditions Cracks on the floors & walls Standing water near the stores Spillage & bird faeces in the stores/stairs & floors Presence of grains germs in the flour. 3 INTRODUCTION In order to improve the shelf life of the flour, the following additional precautions should be taken by millers • Use clean & fumigated grains for milling. • Use scouring machines in the cleaning line. • Set cleaning machines with optimum efficiency to separate out all the impurities from the millets grains. • Clean the dead pockets of the cleaning line frequently, to get rid of non-moving grains at the elevator bottom & outlets, grains conveyor troughs, and tempered grain conveyors. • Fumigate empty Grains bag. 4 INTRODUCTION In order to improve the shelf life of the flour, the following additional precautions should be taken by millers Before milling, use scourers to remove dirt in tempered grains. Regularly clean the milling Equipment's and machinery. Fumigate packing materials before every use. Frequently fumigate bins & conveyors. Always keep the parking area & the flour storage area clean.