Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Joan Plowright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuart Golland Papers (MS 459) - Book Collection

Stuart Golland Papers (MS 459) - Book Collection Title Author/Publisher/Year Shelf Number Medea and other plays / Euripides ; translated and with an Euripides. (Harmondsworth : Penguin 1963.) Stuart Golland Collection/1 introduction by Philip Vellacott. The stirrings in Sheffield on Saturday night / Alan Cullen ; Cullen, Alan. (London : Eyre Methuen 1974.) Stuart Golland Collection/2 introductions by Alan Cullen and Colin George ; foreword by John Hodgson. The Shrewsbury three : strikes, pickets and 'conspiracy' / by Jim Arnison, Jim. (London : Lawrence and Wishart Stuart Golland Collection/3 Arnison ; foreword by Bert Ramelson. 1974.) Being an actor / Simon Callow. Callow, Simon, (Harmondsworth : Penguin Stuart Golland Collection/4 1995.) The Caucasian chalk circle / Bertolt Brecht ; translated by James and Brecht, Bertolt, (London : Methuen 1963, Stuart Golland Collection/5 Tania Stern, with W.H. Auden. c1960.) Saint Joan of the stockyards / Bertolt Brecht ; translated by Frank Brecht, Bertolt, (London : Eyre Methuen 1976.) Stuart Golland Collection/6 Jones. An actor prepares / Constantin Stanislavsky ; translated by Elizabeth Stanislavsky, Konstantin, (London : Geoffrey Stuart Golland Collection/7 Reynolds Hapgood. Bles 1937.) The miners' strike in South Yorkshire, 1926 / by J.A. Peck ; map by Peck, John Antony. (Sheffield : University of Stuart Golland Collection/8 H. Walkland ; illustrations by G.N.J. Wheeler. Sheffield Institute of Education 1970.) Touched / Stephen Lowe. Lowe, Stephen, (Todmorden : Woodhouse Stuart Golland Collection/9 Books 1979, c1977.) Le Tartuffe : comédie / Molière ; avec une notice biographique, une Molière, (Paris : Larousse 1971.) Stuart Golland Collection/10 notice historique er littéraire, un lexique, des notes explicatives, une documentation thématique, des jugements, un questionnaire et des sujets de devoirs par J.P. -

The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama in John Osborne's

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (September. 2018) 77-80 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama In John Osborne’s “ Look Back In Anger” Sadaf Zaman Lecturer University of Bisha Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Sadaf Zaman ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission:16-09-2018 Date of acceptance: 01-10-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- John Osborne was born in London, England in 1929 to Thomas Osborne, an advertisement writer, and Nellie Beatrice, a working class barmaid. His father died in 1941. Osborne used the proceeds from a life insurance settlement to send himself to Belmont College, a private boarding school. Osborne was expelled after only a few years for attacking the headmaster. He received a certificate of completion for his upper school work, but never attended a college or university. After returning home, Osborne worked several odd jobs before he found a niche in the theater. He began working with Anthony Creighton's provincial touring company where he was a stage hand, actor, and writer. Osborne co-wrote two plays -- The Devil Inside Him and Personal Enemy -- before writing and submittingLook Back in Anger for production. The play, written in a short period of only a few weeks, was summarily rejected by the agents and production companies to whom Osborne first submitted the play. It was eventually picked up by George Devine for production with his failing Royal Court Theater. Both Osborne and the Royal Court Theater were struggling to survive financially and both saw the production of Look Back in Anger as a risk. -

ED024693.Pdf

DO CUMEN T R UM? ED 024 693 24 TE 001 061 By-Bogard. Travis. Ed. International Conference on Theatre Education and Development: A Report on the Conference Sponsored by AETA (State Department. Washington. D.C.. June 14-18. 1967). Spons Agency- American Educational Theatre Association. Washington. D.C.;Office of Education (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 7-0783 Pub Date Aug 68 Grant- OEG- 1- 7-070783-1713 Note- I28p. Available from- AETA Executive Office. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. 726 Jackson Place. N.V. Washington. D.C. (HC-$2.00). Journal Cit- Educational Theatre Journal; v20 n2A Aug 1968 Special Issue EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-Acoustical Environment. Acting. Audiences. Auditoriums. Creative Dramatics. Drama. Dramatic Play. Dramatics. Education. Facilities. Fine Arts. Playwriting, Production Techniques. Speech. Speech Education. Theater Arts. Theaters The conference reported here was attended by educators and theater professionals from 24 countries, grouped into five discussion sections. Summaries of the proceedings of the discussion groups. each followed by postscripts by individual participants who wished to amplify portions of the summary. are presented. The discussion groups and the editors of their discussions are:"Training Theatre Personnel,Ralph Allen;"Theatre and Its Developing Audience," Francis Hodge; "Developing and Improving Artistic Leadership." Brooks McNamara; "Theatre in the Education Process." 0. G. Brockett; and "Improving Design for the Technical Function. Scenography. Structure and Function," Richard Schechner. A final section, "Soliloquies and Passages-at-Arms." containsselectedtranscriptions from audio tapes of portions of the conference. (JS) Educational Theatrejourna 1. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

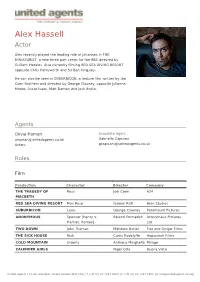

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

A Lively Theatre There's a Revolution Afoot in Theatre Design, Believes

A LIVELY THEatRE There’s a revolution afoot in theatre design, believes architectural consultant RICHARD PILBROW, that takes its cue from the three-dimensional spaces of centuries past The 20th century has not been a good time for theatre architecture. In the years from the 1920s to the 1970s, the world became littered with overlarge, often fan-shaped auditoriums that are barren in feeling and lacking in intimacy--places that are seldom conducive to that interplay between actor and audience that lies at the heart of the theatre experience. Why do theatres of the 19th century feel so much more “theatrical”? And why do so many actors and audiences prefer the old to the new? More generally, does theatre architecture really matter? There are some that believe that as soon as the house lights dim, the audience only needs to see and hear what happens on the stage. Perhaps audiences don’t hiss, boo and shout during a performance any more, but most actors and directors know that an audience’s reaction critically affects the performance. The nature of the theatre space, the configuration of the audience and the intimacy engendered by the form of the auditorium can powerfully assist in the formation of that reaction. A theatre auditorium may be a dead space or a lively one. Theatres designed like cinemas or lecture halls can lay a dead hand on the theatre experience. Happily, the past 20 years have seen a revolution in attitude to theatre design. No longer is a theatre only a place for listening or viewing. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Angry Young Men

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Angry Young Men in British Drama: Analysis and Comparison of The Entertainer and The Kitchen Bachelor Thesis 2020 Karolína Jeníčková Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Beru na vědomí, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách a o změně a doplnění dalších zákonů (zákon o vysokých školách), ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a směrnicí Univerzity Pardubice č. 7/2019, bude práce zveřejněna v Univerzitní knihovně a prostřednictvím Digitální knihovny Univerzity Pardubice. V Pardubicích dne 14. 4. 2020 Karolína Jeníčková ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Mgr. Petra Kalavská, Ph.D., for her kindness and valuable advice during writing of this thesis. I would also like to thank my family for their support throughout my studies. ANNOTATION This bachelor thesis focuses on The Entertainer (1957) by John Osborne and on The Kitchen (1959) by Arnold Wesker, the plays written by playwrights referred to as the Angry Young Men. -

Equity Magazine Autumn 2020 in This Issue

www.equity.org.uk AUTUMN 2020 Filming resumes HE’S in Albert Square Union leads the BEHIND fight for the circus ...THE Goodbye, MASK! Christine Payne Staying safe at the panto parade FIRST SET VISITS SINCE THE LIVE PERFORMANCE TASK FORCE FOR COVID PANDEMIC BEGAN IN THE ZOOM AGE FREELANCERS LAUNCHED INSURANCE? EQUITY MAGAZINE AUTUMN 2020 IN THIS ISSUE 4 UPFRONT Exclusive Professional Property Cover for New General Secretary Paul Fleming talks Panto Equity members Parade, equality and his vision for the union 6 CIRCUS RETURNS Equity’s campaign for clarity and parity for the UK/Europe or Worldwide circus cameras and ancillary equipment, PA, sound ,lighting, and mechanical effects equipment, portable computer 6 equipment, rigging equipment, tools, props, sets and costumes, musical instruments, make up and prosthetics. 9 FILMING RETURNS Tanya Franks on the socially distanced EastEnders set 24 GET AN INSURANCE QUOTE AT FIRSTACTINSURANCE.CO.UK 11 MEETING THE MEMBERS Tel 020 8686 5050 Equity’s Marlene Curran goes on the union’s first cast visits since March First Act Insurance* is the preferred insurance intermediary to *First Act Insurance is a trading name of Hencilla Canworth Ltd Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under reference number 226263 12 SAFETY ON STAGE New musical Sleepless adapts to the demands of live performance during the pandemic First Act Insurance presents... 14 ONLINE PERFORMANCE Lessons learned from a theatre company’s experiments working over Zoom 17 CONTRACTS Equity reaches new temporary variation for directors, designers and choreographers 18 MOVEMENT DIRECTORS Association launches to secure movement directors recognition within the industry 20 FREELANCERS Participants in the Freelance Task Force share their experiences Key features include 24 CHRISTINE RETIRES • Competitive online quote and buy cover provided by HISCOX. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible.