Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N

MS-372 The Museum of Northern Arizona Easton Collection Center 3101 N. Fort Valley Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001 (928)774-5211 ext. 256 Title Harold Widdison Rock Art collection Dates 1946-2012, predominant 1983-2012 Extent 23,390 35mm color slides, 6,085 color prints, 24 35mm color negatives, 1.6 linear feet textual, 1 DVD, 4 digital files Name of Creator(s) Widdison, Harold A. Biographical History Harold Atwood Widdison was born in Salt Lake City, Utah on September 10, 1935 to Harold Edward and Margaret Lavona (née Atwood) Widdison. His only sibling, sister Joan Lavona, was born in 1940. The family moved to Helena, Montana when Widdison was 12, where he graduated from high school in 1953. He then served a two year mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1956 Widdison entered Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, graduating with a BS in sociology in 1959 and an MS in business in 1961. He was employed by the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington DC before returning to graduate school, earning his PhD in medical sociology and statistics from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio in 1970. Dr. Widdison was a faculty member in the Sociology Department at Northern Arizona University from 1972 until his retirement in 2003. His research foci included research methods, medical sociology, complex organization, and death and dying. His interest in the latter led him to develop one of the first courses on death, grief, and bereavement, and helped establish such courses in the field on a national scale. -

The Native Fish Fauna of Major Drainages East of The

THE NATIVE FISH FAUNA OF MAJOR DRAINAGES EAST OF THE CONTINENTAL DIVIDE IN NEW MEXICO A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Biology Eastern New Mexico University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements fdr -the7Degree: Master of Science in Biology by Michael D. Hatch December 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction Study Area Procedures Results and Discussion Summary Acknowledgements Literature Cited Appendices Abstract INTRODUCTION r (t. The earliest impression of New Mexico's native fish fauna =Ems during the 1850's from naturalists attached to various government survey parties. Without the collections from these and other early surveys, the record of the native fish fauna would be severely deficient because, since that time, some 1 4 native species - or subspecies of fish have become extirpated and the ranges of an additionial 22 native species or subspecies have become severly re- stricted. Since the late Miocene, physiographical changes of drainages have linked New Mexico, to varying degrees, with contemporary ichthyofaunal elements or their progenitors from the Rocky Mountains, the Great Plains, the Chihuahuan Desert, the Mexican Plateau, the Sonoran Desert and the Great Basin. Immigra- tion from these areas contributed to the diversity of the state's native ichthyofauna. Over the millinea, the fate of these fishes waxed and waned in ell 4, response to the changing physical and _chenaca-l-conditions of the surrounding environment. Ultimately, one of the most diverse fish faunas of any of the interior southwestern states developed. Fourteen families comprising 67 species of fish are believed to have occupied New Mexico's waters historically, with strikingly different faunas evolving east and west of the Continental Divide. -

The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa

Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Introduction 20 The African archeological record of 43-28 ka as a comparison 21 A - The Aurignacian has no direct equivalent in Africa 21 B - Archaic hominins persist in Africa through much of the Late Pleistocene 24 C - High modification symbolic artifacts in Africa and Eurasia 24 Conclusions 26 Acknowledgements 26 References cited 27 To cite this article Tryon C. A. , 2015 - The Aurignacian Viewed from Africa, in White R., Bourrillon R. (eds.) with the collaboration of Bon F., Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe, Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University, P@lethnology, 7, 19-33. http://www.palethnologie.org 19 P@lethnology | 2015 | 19-33 Aurignacian Genius: Art, Technology and Society of the First Modern Humans in Europe Proceedings of the International Symposium, April 08-10 2013, New York University THE AURIGNACIAN VIEWED FROM AFRICA Christian A. TRYON Abstract The Aurignacian technocomplex in Eurasia, dated to ~43-28 ka, has no direct archeological taxonomic equivalent in Africa during the same time interval, which may reflect differences in inter-group communication or differences in archeological definitions currently in use. Extinct hominin taxa are present in both Eurasia and Africa during this interval, but the African archeological record has played little role in discussions of the demographic expansion of Homo sapiens, unlike the Aurignacian. Sites in Eurasia and Africa by 42 ka show the earliest examples of personal ornaments that result from extensive modification of raw materials, a greater investment of time that may reflect increased their use in increasingly diverse and complex social networks. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, Memphis, Tn, 17-18 April 2012

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, MEMPHIS, TN, 17-18 APRIL 2012 Paleolithic Foragers of the Hrazdan Gorge, Armenia Daniel Adler, Anthropology, University of Connecticut, USA B. Yeritsyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA K. Wilkinson, Archaeology, Winchester University, UNITED KINGDOM R. Pinhasi, Archaeology, UC Cork, IRELAND B. Gasparyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA For more than a century numerous archaeological sites attributed to the Middle Paleolithic have been investigated in the Southern Caucasus, but to date few have been excavated, analyzed, or dated using modern techniques. Thus only a handful of sites provide the contextual data necessary to address evolutionary questions regarding regional hominin adaptations and life-ways. This talk will consider current archaeological research in the Southern Caucasus, specifically that being conducted in the Republic of Armenia. While the relative frequency of well-studied Middle Paleolithic sites in the Southern Caucasus is low, those considered in this talk, Nor Geghi 1 (late Middle Pleistocene) and Lusakert Cave 1 (Upper Pleistocene), span a variety of environmental, temporal, and cultural contexts that provide fragmentary glimpses into what were complex and evolving patterns of subsistence, settlement, and mobility over the last ~200,000 years. While a sample of two sites is too small to attempt a serious reconstruction of Middle Paleolithic life-ways across such a vast and environmentally diverse region, the sites -

File1\Home\Cwells\Personal\Service

SAS Bulletin Newsletter of the Society for Archaeological Sciences Volume 28 number 4 Winter 2005 Archaeological Science The process involves rehydrating the eyes and optical on ‘All Hallows Eve’ nerves, preparing the tissues for chemical processing, embedding the tissues in paraffin, slicing the specimens for By the time you receive this issue of the SAS Bulletin, microscopic viewing, applying stains to highlight selected Celtic Samhain, as well as the pumpkin-studded American cellular characteristics, and finally examining the tissues under version called Halloween, will have passed. Still, in this season a microscope. of “days of the dead,” I’m inspired to share with you an interesting bit of archaeological science being conducted on— Tests were conducted for eye diseases, such as glaucoma you guessed it—mummies. and macular degeneration, but Lloyd says there are many more systemic ailments that can be found by examining the eyes. In late October, ophthalmologist William Lloyd of the “During modern-day eye exams we can see signs of diabetes, University of California-Davis School of Medicine dissected high blood pressure, various cancers, nutritional deficiencies, and examined the eyes of two north Chilean mummies for fetal alcohol syndrome and even early signs of HIV infection,” evidence of various diseases and medical conditions. One of said Lloyd. “These same changes are visible under the the eyes belonged to a Tiwanaku male who was 2 years old microscope.” when he died 1,000 years ago, and the other is from a Tiwanaku female, who was approximately 23 years old when she died This edition of the SAS Bulletin contains news about other 750 years ago. -

The Role of North Africa in the Emergence and Development of Modern Behaviors: an Integrated Approach

Afr Archaeol Rev (2017) 34:447–449 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-017-9276-9 INTRODUCTION The Role of North Africa in the Emergence and Development of Modern Behaviors: An Integrated Approach Emilie Campmas & Emmanuelle Stoetzel & Aicha Oujaa & Eleanor Scerri Published online: 12 December 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2017 This special issue of African Archaeological Review, Modern Human Behavior: A View from North Africa^ entitled BThe Role of North Africa in the Emergence organized by Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, Nick Barton, and and Development of Modern Behaviors: an Integrated Nabiha Aouadi during the UISPP conference at Burgos Approach,^ is the outcome of a session held at the 23rd in 2014 (Mutri 2016). Society of Africanist Archaeologists (SAfA) meeting TheuseofthetermBmodern behaviors^ is to- held in Toulouse, France, from June 26 to July 2, day considered to be contentious, because it is 2016. The session was organized by Emilie Campmas, based on a number of assumptions, including that Emmanuelle Stoetzel, Aicha Oujaa, and Eleanor Scerri. (1) modern behaviors are associated with modern The special issue builds on a series of recent meetings humans, (2) behavioral complexity evolves linearly and publications focusing on the same topic and region, with archaic to modern human forms, (3) features such as the meeting BModern Origins: A North African considered to be hallmarks of modern behavior Perspective,^ organized by Jean-Jacques Hublin and derive from specific European archaeological re- Shannon McPherron at the Max Planck Institute in cords, and (4) the determination of features consid- 2007 (Hublin and McPherron 2012), the session ered as either Bmodern^ or Bnon-modern^ can only BNorthwest African Prehistory: Recent Work, New be a matter of qualitative opinion. -

New Insights on Final Epigravettian Funerary Behavior at Arene Candide Cave (Western Liguria, Italy)

doie-pub 10.4436/jass.96003 ahead of print JASs Reports doi: 10.4436/jass.89003 Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 96 (2018), pp. 161-184 New insights on Final Epigravettian funerary behavior at Arene Candide Cave (Western Liguria, Italy) Vitale Stefano Sparacello1, 2, Stefano Rossi3, 4, Paul Pettitt2, Charlotte Roberts2, Julien Riel-Salvatore5 & Vincenzo Formicola6 1) Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, PACEA, UMR 5199, Batiment B8, Allée Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, CS 50023, 33615 Pessac cedex e-mail: [email protected] 2) Department of Archaeology, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, United Kingdom 3) Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio per la città metropolitana di Genova e le province di Imperia, La Spezia e Savona, Via Balbi, 10, 16126 Genova, Italy 4) DISTAV, Università di Genova, Corso Europa, 26, 16132 Genova, Italy 5) Département d’Anthropologie, Université de Montréal, Pavillon Lionel-Groulx, 3150 rue Jean-Brillant, H3T 1N8 Montréal (QC), Canada 6) Department of Biology, Università di Pisa, Via Derna 1, 56126 Pisa, Italy Summary - We gained new insights on Epigravettian funerary behavior at the Arene Candide cave through the osteological and spatial analysis of the burials and human bone accumulations found in the cave during past excavations. Archaeothanathological information on the human skeletal remains was recovered from diaries, field pictures and notes, and data from recent excavations was integrated. The secondary deposits have traditionally been interpreted as older burials that were disturbed to make space for new inhumations. Our results suggest that those disturbances were not casual: older burials were intentionally displaced to bury younger inhumations. Subsequently, some skeletal elements, especially crania, were arranged around the new burial; these were often placed within stone niches. -

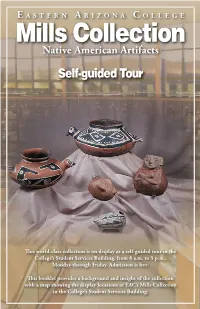

Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-Guided Tour

E ASTE RN A RIZONA C OLLEGE Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-guided Tour This world-class collection is on display as a self-guided tour in the College’s Student Services Building, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Admission is free. This booklet provides a background and insight of the collection with a map showing the display locations of EAC’s Mills Collection in the College’s Student Services Building. MillsHistory Collection of the rdent avocational archaeologists Jack Aand Vera Mills conducted extensive excavations on archaeological sites in Southeastern Arizona and Western New Mexico from the 1940s through the 1970s. They restored numerous pottery vessels and amassed more than 600 whole and restored pots, as well as over 5,000 other artifacts. Most of their work was carried out on private land in southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico. Towards the end of their archaeological careers, Jack and Vera Mills wished to have their collection kept intact and exhibited in a local facility. After extensive negotiations, the Eastern Arizona College Foundation acquired the collection, agreeing to place it on public display. Showcasing the Mills Collection was a weighty consideration when the new Student Services building at Eastern Arizona College was being planned. In fact, the building, and particularly the atrium area of the lobby, was designed with the Collection in mind. The public is invited to view the display. Admission is free and is open for self-guided tours during regular business hours, Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. -

TJ Ruin: Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico

GILA CLIFF DWELLINGS NATIONAL MONUMENT NEW MEXICO PETER J. MCKENNA JAMES E. BRADFORD SOUTHWEST CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER PROFESSIONAL PAPERS NUMBER 21 PUBLISHED REPORTS OF THE SOUTHWEST CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER 1. Larry Murphy, James Baker, David Buller, James Delgado, Rodger Kelly, Daniel Lenihan, David McCulloch, David Pugh; Diana Skiles; Brigid Sullivan. Submerged Cultural Resources Survey: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reves-Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1984. 2. Toni Carrell. Submerged Cultural Resources Inventory: Portions of Point Reyes National Seashore and Point Reves-Farallon Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1984. 3. Edwin C. Bearss. Resources Study: Lyndon B. Johnson and the Hill Country. 1937-1963. Division of Conservation, 1984. 4. Edwin C. Bearss. Historic Structures Report: Texas White House. Division of Conservation, 1986. 5. Barbara Holmes. Historic Resource Study of the Barataria Unit of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. Division of History, 1986. " 6. Steven M. Burke and Marlys Bush-Thurber. Southwest Region Headquarters Building. Santa Fe. New Mexico: A Historic Structure Report. Division of Conservation, 1985. 7. Toni Carrell. Submerged Cultural Resources Site Report: Noquebav. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1985. 8. Daniel J. Lenihan, Tony Carrell, Thom Holden, C. Patrick Labadie, Larry Murphy, Ken Vrana. Submerged Cultural Resources Study: Isle Royale National Park. Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, 1987. 9. J. Richard Ambler. Archeological Assessment: Navajo National Monument. Division of Anthropology, 1985. 10. John S. Speaker, Joanna Chase, Carol Poplin, Herschel Franks, R. Christopher Goodwin. Archeological Assessment: Barataria Unit. Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. Division of Anthropology, 1986. -

PSW-31-1-2.Pdf

POTTERY SOUTHWEST Volume 31, No. 2 APRIL 2015 SPRING-SUMMER 2015 (Part II) ISSN 0738-8020 MISSION STATEMENT Pottery Southwest, a scholarly journal devoted to the prehistoric and historic pottery of the Greater Southwest (http://www.unm.edu/~psw/), provides a venue for students, professional, and avocational archaeologists in which to publish scholarly articles as well as providing an opportunity to share questions and answers. Published by the Albuquerque Archaeological Society since 1974, Pottery Southwest is available free of charge on its website which is hosted by the Maxwell Museum of the University of New Mexico. CONTENTS Page Class Size Matters: An Examination of Size Classes in Ceramic Bowls from Classic Era Sites in New Mexico, P. F. Przystupa ........................................... 2-22 What Mean These Mimbres Bird Motifs? Marc Thompson, Patricia A. Gilman and Kristina C. Wyckoff ............................................................. 23-29 Comments on Anasazi Organic Black-on-white Pottery: A New Paradigm, Pottery Southwest, Vol. 30, Nos. 3-4 Owen Severence......................................................................................................... 30-31 Joe Lally ..................................................................................................................... 32-35 Response Rod Swenson ........................................................................................................ 36-38 CDs Available from the Albuquerque Archaeological Society ....................................... -

Mexican Macaws: Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains from the Southwest

Mexican Macaws: Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains from the Southwest Item Type Book; text Authors Hargrave, Lyndon L. Publisher University of Arizona Press (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents Download date 30/09/2021 22:04:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/595459 MEXICAN MACAWS Scarlet Macaw. Painting by Barton Wright. ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA NUMBER 20 MEXICAN MACAWS LYNDON L. HARGRAVE Comparative Osteology and Survey of Remains From the Southwest THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS TUCSON, ARIZONA 1970 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS Copyright © 1970 The Arizona Board of Regents All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the U.S.A. I. S. B. N.-0-8165-0212-9 L. C. No. 72-125168 PREFACE Any contribution to ornithology and its application to prehistoric problems of avifauna as complex as the present study of macaws, presents many interrelated problems of analysis, visual and graphic presentation, and text form. A great many people have contributed generously of their time, knowledge, and skills toward completion of the present study. I wish here to express my gratitude for this invaluable aid and interest. I am grateful to the National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, and its officials for providing the funds and facilities at the Southwest Archeological Center which have enabled me to carryon this project. In particular I wish to thank Chester A. Thomas, Director of the Center. I am further grateful to the Museum of Northern Arizona and Edward B. Danson, Director, for providing institutional sponsorship for the study as well as making available specimen material and information from their collections and records. -

The Genomic History of the Iberian Peninsula Over the Past 8000 Years

1 The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years 2 3 Iñigo Olalde1*, Swapan Mallick1,2,3, Nick Patterson2, Nadin Rohland1, Vanessa Villalba- 4 Mouco4,5, Marina Silva6, Katharina Dulias6, Ceiridwen J. Edwards6, Francesca Gandini6, Maria 5 Pala6, Pedro Soares7, Manuel Ferrando-Bernal8, Nicole Adamski1,3, Nasreen 6 Broomandkhoshbacht1,3, Olivia Cheronet9, Brendan J. Culleton10, Daniel Fernandes9,11, Ann 7 Marie Lawson1,3, Matthew Mah1,2,3, Jonas Oppenheimer1,3, Kristin Stewardson1,3, Zhao Zhang1, 8 Juan Manuel Jiménez Arenas12,13,14, Isidro Jorge Toro Moyano15, Domingo C. Salazar-García16, 9 Pere Castanyer17, Marta Santos17, Joaquim Tremoleda17, Marina Lozano18,19, Pablo García 10 Borja20, Javier Fernández-Eraso21, José Antonio Mujika-Alustiza21, Cecilio Barroso22, Francisco 11 J. Bermúdez22, Enrique Viguera Mínguez23, Josep Burch24, Neus Coromina24, David Vivó24, 12 Artur Cebrià25, Josep Maria Fullola25, Oreto García-Puchol26, Juan Ignacio Morales25, F. Xavier 13 Oms25, Tona Majó27, Josep Maria Vergès18,19, Antònia Díaz-Carvajal28, Imma Ollich- 14 Castanyer28, F. Javier López-Cachero25, Ana Maria Silva29,30,31, Carmen Alonso-Fernández32, 15 Germán Delibes de Castro33, Javier Jiménez Echevarría32, Adolfo Moreno-Márquez34, 16 Guillermo Pascual Berlanga35, Pablo Ramos-García36, José Ramos Muñoz34, Eduardo Vijande 17 Vila34, Gustau Aguilella Arzo37, Ángel Esparza Arroyo38, Katina T. Lillios39, Jennifer Mack40, 18 Javier Velasco-Vázquez41, Anna Waterman42, Luis Benítez de Lugo Enrich43,44, María Benito 19 Sánchez45, Bibiana Agustí46,47, Ferran Codina47, Gabriel de Prado47, Almudena Estalrrich48, 20 Álvaro Fernández Flores49, Clive Finlayson50,51,52,53, Geraldine Finlayson50,52,53, Stewart 21 Finlayson50,54, Francisco Giles-Guzmán50, Antonio Rosas55, Virginia Barciela González56,57, 22 Gabriel García Atiénzar56,57, Mauro S.