Pakistan Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sb List for 19.11.2018(Monday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 19 NOVEMBER, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. RFA Wazir Ahmad Khan Khurshid Ahmed Khattak, 196/2005(With V/s (Date By Court) Muhammad Amin Khattak Lachi CMs Reayat Khan Khattak 100,228/09,C.ms.4 Abdul Samad Khan, Syed Mir 75,409/12) Muhammad, Khalid Khan, M.Amin Khattak, Arshad Jamal Qureshi i RFA 181/2005 Cheif Editor Daily Statesman Ijaz Anwar V/s Damages, Rs.20 million Senior Part Reayat Khan Khattak Abdul Samad Khan, Adeel Anwar Jehangir, , M.Amin Khattak, Adnan Khattak, Ibrahim Shah ii RFA 249/2005 With Attiqur Rehman M.Amin Khattak V/s CMs 101-P/2009 Reayat Khan Khattak Ijaz Anwar, Abdul Samad Khan, Khurshid Ahmed Khattak, Arshad Jamal Qureshi iii RFA 84/2011 with Muhamamd Zareen Arshad Jamal Qureshi V/s C.M.406/11 Wazir Ahmad Khan and others Muhammad Amin Khattak, Ijaz Anwar, Abdul Samad Khan Zaida, Muhammad Amin Khattak Lachi, Adnan Khattak, Arshad Jamal MOTION CASES 1. Cr.M(TA) Farhad Fazal Shah Mohmand 87/2018() V/s (Date By Court) The State AG KPK 2. CM(TA) 85/2018() Sharif Khan Muhammad Hasnain V/s Late Sher Dil Khan 3. CM(TA) 86/2018() Abbottabad International Sardar Saadat Ali Medical College V/s Federation of Pakistan MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 95 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 19 NOVEMBER, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 4. -

INDUS DELTA, PAKISTAN: Economic Costs of Reduction in Freshwater Flows

water allocationdecisions. factored intoriverbasinplanning,or benefits of water-basedecosystemsarerarely economic users ofwater.Yettheeconomic schemes, Pakistan’secosystems,too,are hydropower dams, reservoirs,irrigationand as water tolarge-scale,commercialusessuch imperative that favours theallocationof Contrary tothedominantdevelopment economically norecologicallyoptimal. decisions beingmadethatareneither needs has oftenledtowaterallocation Failure torecognisedownstreamecosystem heavily byupstreamwaterabstraction. end of rivers,havebeenimpactedmost the at lie and marineregions,becausethey Coastal ecosystems. needs ofdownstream many cases, left insufficientflowtomeetthe of large volumesofwaterfromrivershas,in particular there isconcernthattheabstraction exacting a heavytollontheenvironment.In This impressive irrigationsystemis,however, world. the irrigated torain-fedlandratioin highest the farmland, affordingPakistan system feedsmorethan15millionhectaresof than 1.65 million km(IRIN2001).The more watercourses witharunninglengthof 89,000 conveyance lengthof57,000km,and head works, 43maincanalswitha or barrages 19 three majorstoragereservoirs, comprises Pakistan’s vastirrigationnetwork Pakistan Water-based developmentsin flows reduction infreshwater economic costsof INDUS DELTA,PAKISTAN: VALUATION #5:May2003 CASE STUDIESINWETLAND Integrating Wetland Economic Values into River Basin Management Managing freshwater flows in the The economic costs and losses arising from Indus River such omissions can be immense, and often The Indus River has -

Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season

Journal of Asian Civilizations -1- Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season Paolo Biagi ABSTRACT In January-February 2009 archaeological surveys were conducted in three different regions of Lower Sindh, from Ranikot, in the north, to the Makli Hills, in the south. They resulted in the discovery of many sites and flint spots within a territory the archaeology of which was previously poorly known. This paper is aimed at the description of these finds, their cultural attribution and, whenever possible, absolute chronology. Particular attention has been paid to the radiocarbon chronology of the sites located on the rocky outcrops that rise from the alluvial plain of the Indus delta, a few of which indicate that seafaring along the northern shores of the Arabian Sea was already active at least since the very beginning of the seventh millennium uncal BP. 1. PREFACE This paper is a preliminary report of the surveys carried out in January and February 2009 in Lower Sindh, between Ranikot, in the north, and the Makli Hills, in the south. The scope of the surveys, which were part of a joint venture by Ca’ Foscari University, Venice (I) and Sindh University, Jamshoro (PK), was to discover new archaeological sites in a territory insufficiently explored, and define their cultural attribution and absolute chronology by radiocarbon dating. Although some parts of the above region had already been surveyed by other authors (see, for instance, MAJUMDAR, 1934; COUSENS, 1998; FRANKE-VOGT, 1999; FLAM, 2006), our attention focused mainly on territories never accurately investigated before. The surveys were conducted by systematic walking in the three main, well- defined areas described in the following chapters (fig. -

The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River

16 The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River Asif Inam1, Peter D. Clift2, Liviu Giosan3, Ali Rashid Tabrez1, Muhammad Tahir4, Muhammad Moazam Rabbani1 and Muhammad Danish1 1National Institute of Oceanography, ST. 47 Clifton Block 1, Karachi, Pakistan 2School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 4Fugro Geodetic Limited, 28-B, KDA Scheme #1, Karachi 75350, Pakistan 16.1 INTRODUCTION glaciers (Tarar, 1982). The Indus, Jhelum and Chenab Rivers are the major sources of water for the Indus Basin The 3000 km long Indus is one of the world’s larger rivers Irrigation System (IBIS). that has exerted a long lasting fascination on scholars Seasonal and annual river fl ows both are highly variable since Alexander the Great’s expedition in the region in (Ahmad, 1993; Asianics, 2000). Annual peak fl ow occurs 325 BC. The discovery of an early advanced civilization between June and late September, during the southwest in the Indus Valley (Meadows and Meadows, 1999 and monsoon. The high fl ows of the summer monsoon are references therein) further increased this interest in the augmented by snowmelt in the north that also conveys a history of the river. Its source lies in Tibet, close to sacred large volume of sediment from the mountains. Mount Kailas and part of its upper course runs through The 970 000 km2 drainage basin of the Indus ranks the India, but its channel and drainage basin are mostly in twelfth largest in the world. Its 30 000 km2 delta ranks Pakiistan. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Single Bench List for 02.03.2018

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 02 MARCH, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH Court No: 2 MOTION CASES 1. CM Corr Waseem Akram Ishtiaq Ahmad 54/2018(in BA V/s 19/2018) The State and Others 2. W.P 655/2018() Zafar Ali Sabitullah Khan Khalil V/s Lal Khan and Others 3. Cr.A 889/2017() Fawad Ali Anwar Hussain V/s (Date By Court) The State etc 4. Cr.M(BCA) Malang LRS of Deceased Qazi Intikhab Ahmad 2766/2017() Sakheem Gul V/s Sajjad and Others 5. C.R 525/2016 Pir Hashmat Ali & Others Raja Muhammad Ijaz (Others) with V/s o/n(Declaration) Muhammad Hussain & Others Mukamil Shah Taskeen 6. C.R 597/2017 with Ali Abbas Zafar Ahmad Awan cm. 961/2017() V/s Mst. Naeema Kausar & Others MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 52 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR FRIDAY, 02 MARCH, 2018 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH Court No: 2 MOTION CASES 7. C.R 78/2018 with Majid and Others Ayaz Khan Khalil cm. 181/2018 (m)() V/s Muhammad Yousaf etc 8. C.R 100/2018 with Govt of KPK and Others Advocate General c.m 145-P/2018() V/s Saleem Numan and Others 9. Cr.R Naqeeb Ullah Mudassir Ali Bangash 149/2016(Enhance V/s the sentence) Hafeez Ullah and another Abid Ali, A.A.G 10. C.R 700/2014 Mst. Kiran Zia Ur Rehman (Others)(Against V/s decree(Stay Mohib Ullah Khan and another Mukamil Khan, Naveed ur confirmed on Rehman, Farmanullah Sailab, 27/10/14)) Farooq Malik 11. -

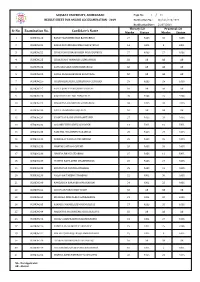

Gujarat University, Ahmedabad Result Sheet for Online Ccc Examination

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY, AHMEDABAD Page No.: 1 / 44 RESULT SHEET FOR ONLINE CCC EXAMINATION - 2019 Notification No. : GU/CCC/123/2019 Notification Date : 21/07/2019 Theory-50 Practical-50 Sr No. Examination No. Candidate's Name Marks Status Marks Status 1 GUB039220 BAROT MANISHKUMAR BACHUBHAI 27 PASS 36 PASS 2 GUB039221 BARIA DEVENDRAKUMAR PARVATBHAI 14 FAIL 5 FAIL 3 GUB039222 CHAUDHARI JIGNASHABEN MAHADEVBHAI 27 PASS 27 PASS 4 GUB039223 CHAUDHARY MINABEN LAXMANBHAI AB AB AB AB 5 GUB039224 SANGADA GEETABEN BHANABHAI AB AB AB AB 6 GUB039225 PATEL PRAKASHKUMAR SHANTILAL AB AB AB AB 7 GUB039226 CHANDRESHBHAI LAXMANSINH CHAUHAN 29 PASS 29 PASS 8 GUB039227 PATEL SHREYANKKUMAR VADILAL AB AB AB AB 9 GUB039228 SAGATHIYA HITESH PUNJABHAI 28 PASS 26 PASS 10 GUB039229 MAKWANA KIRANBHAI GOBARBHAI 33 PASS 33 PASS 11 GUB039230 PATEL USHABEN KANJIBHAI AB AB AB AB 12 GUB039231 VAGHELA PRADIPSINH ROHITSINH 27 PASS 31 PASS 13 GUB039232 SOLANKI VIPULSINH JAVANSINH 13 FAIL 10 FAIL 14 GUB039233 PANCHAL NILAMBEN NARANDAS 25 PASS 27 PASS 15 GUB039234 SONAGRA PRAHLAD VELSHIBHAI 25 PASS 32 PASS 16 GUB039235 MANVAR JAYRAM GOVIND 28 PASS 36 PASS 17 GUB039236 CHAVDA BHALU SEJABHAI 27 PASS 12 FAIL 18 GUB039237 TRIVEDI KAPILABEN DHANESHWAR 26 PASS 27 PASS 19 GUB039238 KODIYATAR PANCHA KISABHAI 25 PASS 26 PASS 20 GUB039239 VALA PARITABEN PITHABHAI 22 FAIL 30 PASS 21 GUB039240 KANGASIYA KARANBHAI MANABHAI 24 FAIL 25 PASS 22 GUB039241 CHHIPA IRFANAHMED YUSUF AB AB AB AB 23 GUB039242 BHAGORA DIMPALBEN SANKARBHAI 21 FAIL 32 PASS 24 GUB039243 PARMAR NIRMALABEN MANGALDAS 27 PASS -

List of Stations

Sr # Code Division Name of Retail Outlet Site Category City / District / Area Address 1 101535 Karachi AHMED SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI EAST DADABHOY NOROJI ROAD AKASHMIR ROAD 2 101536 Karachi CHAND SUPER SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI WEST PSO RETAIL DEALERSST/1-A BLOCK 17F 3 101537 Karachi GLOBAL PETROLEUM SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI EAST PLOT NO. 234SECTOR NO.3, 4 101538 Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST 1-A BLOCK 6FEDERAL B AREADISTT K 5 101540 Karachi RAANA GASOLINE N/V CF KARACHI WEST SERVICE STATIONPSO RETAIL DEALERAPWA SCHOOL LIAQA 6 101543 Karachi SHAHGHAZI P/S N/V DFA MALIR SURVEY#81,45/ 46 KM SUPER HIGHWAY 7 101544 Karachi GARDEN PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH OPP FATIMA JINNAHGIRLS HIGH SCHOOLN 8 101545 Karachi RAZA PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH 282/2 LAWRENCE ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI-SOUTH 9 101548 Karachi FANCY SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST-1A BLOCK 10FEDERAL B AREADISTT KARACHI WEST 10 101550 Karachi SIDDIQI SERVIC STATION S/S DFB KARACHI EAST RASHID MINHAS ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI EAST 11 101555 Karachi EASTERN SERIVCE STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST D-201 SITEDIST KARACHI-WEST 12 101562 Karachi AL-YASIN FILL STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST ST-1/2 15-A/1 NORTHKAR TOWNSHIP KAR WEST 13 101563 Karachi DUREJI FILLING STATION S/S DFA LASBELA KM-4/5 HUB-DUREJI RDPATHRO HUBLASBE 14 101566 Karachi R C D FILLING STATION N/V DFA LASBELA HUB CHOWKI LASBELADISTT LASBELA 15 101573 Karachi FAROOQ SERVICE CENTRE N/V CF KARACHI WEST N SIDDIQ ALI KHAN ROADCHOWRANGI NO-3NAZIMABADDISTT 16 101577 Karachi METRO SERVICE STATION -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Muslims in India

Studies on Muslims in India An Annotated Bibliography With Focus on Muslims in Andhra Pradesh (Volume: ) EMPLOYMENT AND RESERVATIONS FOR MUSLIMS By Dr.P.H.MOHAMMAD AND Dr. S. LAXMAN RAO Supervised by Dr.Masood Ali Khan and Dr.Mazher Hussain CONFEDERATION OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS (COVA) Hyderabad (A. P.), India 2003 Index Foreword Preface Introduction Employment Status of Muslims: All India Level 1. Mushirul Hasan (2003) In Search of Integration and Identity – Indian Muslims Since Independence. Economic and Political Weekly (Special Number) Volume XXXVIII, Nos. 45, 46 and 47, November, 1988. 2. Saxena, N.C., “Public Employment and Educational Backwardness Among Muslims in India”, Man and Development, December 1983 (Vol. V, No 4). 3. “Employment: Statistics of Muslims under Central Government, 1981,” Muslim India, January, 1986 (Source: Gopal Singh Panel Report on Minorities, Vol. II). 4. “Government of India: Statistics Relating to Senior Officers up to Joint-Secretary Level,” Muslim India, November, 1992. 5. “Muslim Judges of High Courts (As on 01.01.1992),” Muslim India, July 1992. 6. “Government Scheme of Pre-Examination Coaching for Candidates for Various Examination/Courses,” Muslim India, February 1992. 7. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Department of Statistics, Government of India, Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Religious Groups in India: 1993-94 (Fifth Quinquennial Survey, NSS 50th Round, July 1993-June 1994), Report No: 438, June 1998. 8. Employment and Unemployment Situation among Religious Groups in India 1999-2000. NSS 55th Round (July 1999-June 2000) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, September 2001. Employment Status of Muslims in Andhra Pradesh 9. -

1 Gggg Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge

gg1 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University 2019-2020 gg 12 Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge Azim Premji University Modern India has a history of a vibrant and active social sector. Many local development organisations, community organizations, social movements and non-governmental organisations populate the space of social action. Such organisations imagine a different future and plan and implement social interventions at different scales, many of which have lasting impact on the lives of people and society. However, their efforts and, more importantly, the learning from these initiatives remains largely unknown not only in the public sphere but also in the worlds of ‘development practice’ and ‘development education’. This shortfall impedes the process of learning and growth across interventions, organizations and time. While most social sector organizations acknowledge this deficiency in documentation and knowledge creation, they find themselves strapped for time and motivation to embark on such efforts. Writing with a sense of reflection and self-analysis which goes beyond mere documentation and creates a platform for learning requires time and space. As a result, their writing is usually limited to documentation captured in grant proposals or project updates or ‘good practices’ literature with inadequate focus on capturing the nuances, boundaries and limitations of action. Recognizing this need, the Azim Premji University launched ‘Stories of Change: Case Study Challenge’ with the objective of encouraging social sector organisations to invest in developing a grounded knowledge base for the sector. We are delighted to report that in the inaugural year of this challenge (2018 – 19) we received 95 cases, covering interventions from education, sustainability, livelihoods, preservation of culture and community health. -

Ca' Foscari and Pakistan Thirty Years of Archaeological Surveys And

150 Years of Oriental Studies at Ca’ Foscari edited by Laura De Giorgi and Federico Greselin Ca’ Foscari and Pakistan Thirty Years of Archaeological Surveys and Excavations in Sindh and Las Bela (Balochistan) Paolo Biagi (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Abstract This paper regards the research carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Sindh and Las Bela province of Balochistan (Pakistan). Until the mid ’80s the prehistory of the two regions was known mainly from the impressive urban remains of the Bronze Age Indus Civilisation and the Pal- aeolithic assemblages discovered at the top of the limestone terraces that estend south of Rohri in Up- per Sindh. Very little was known of other periods, their radiocarbon chronology, and the Arabian Sea coastal zone. Our knowledge radically changed thanks to the discoveries made during the last three decades by the Italian Archaeological Mission. Thanks to the results achieved in these years, the key role played by the north-western regions of the Indian Subcontinent in prehistory greatly improved. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Archaeological Results. – 3 Discussion. – 3.1 The Chert Outcrops. – 3.2 The Late (Upper) Palaeolithic and Mesolithic sites. – 3.3 The Shell Middens of Las Bela Coast. – 3.4 The Indus Delta Country. – 4 Conclusion. Keywords Sindh. Las Bela. Indus delta. Prehistoric sites. Radiocarbon chronology. 1 Introduction Due to its location midway between the Iranian uplands, in the west, and the Thar or Great Indian Desert, in the east, the Indus Valley and Sindh have always played a unique role in the prehistory of south Asia, and the Indian Subcontinent in particular.