Information Processing in Groups GROUP DYNAMICS Definition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GROUP DYNAMICS 7. Group Behavior 7.1. Introduction Group

GROUP DYNAMICS 7. Group Behavior 7.1. Introduction Group behavior in sociology refers to the situations where people interact in large or small groups. The field of group dynamics deals with small groups that may reach consensus and act in a coordinated way. Groups of a large number of people in a given area may act simultaneously to achieve a goal that differs from what individuals would do acting alone, called herd behavior. A large group, crowd or mob, is likely to show examples of group behavior when people gathered in a given place and time act in a similar way for example, joining a protest or march, participating in a fight or acting patriotically. Special forms of large group behavior are: Crowd "hysteria" Spectators - When a group of people gather together on purpose to participate in an event like theatre play, cinema movie, football match, a concert, etc. Public - Exception to the rule that the group must occupy the same physical place. People watching same channel on television may react in the same way, as they are occupying the same type of place, in front of television, although they may physically be doing this all over the world. Group behavior differs from mass actions, which refers to people who behave similarly on a more global scale (for example, shoppers in different shops), while group behavior refers usually to people in one place. If the group behavior is coordinated, then it is called group action. Swarm intelligence is a special case of group behavior where group members interact to fulfill a specific task. -

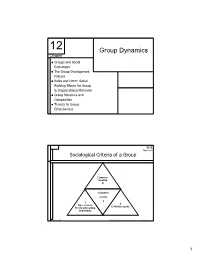

Group Dynamics Chapter

12 Group Dynamics Chapter Groups and Social Exchanges The Group Development Process Roles and Norm: Social Building Blocks for Group & Organizational Behavior Group Structure and Composition Threats to Group Effectiveness 12-3 Figure 12-1 Sociological Criteria of a Group Common identity 4 Collective norms 2 1 3 Two or more Collective goals Freely interacting individuals McGraw-Hill © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 12-4 Table 12-2 Formal Groups Fulfill Organizational Functions 1) Accomplish complex, independent tasks beyond the capabilities of individuals 2) Generate new or creative ideas or solutions 3) Coordinate interdependent efforts 4) Provide a problem-solving mechanism for complex problems 5) Implement complex decisions 6) Socialize and train newcomers McGraw-Hill © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 12-5 Table 12-2 cont. Formal Groups Fulfill Individual Functions 1) Satisfy the individual’s need for affiliation 2) Develop, enhance and confirm individual’s self- esteem and sense of identity 3) Give individuals an opportunity to test and share their perceptions of social reality 4) Reduce the individual’s anxieties and feelings of insecurity and powerlessness 5) Provide a problem-solving mechanism for social and interpersonal problems McGraw-Hill © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 2 12-7 Tuckman’s Five-Stage Theory Figure 12-3 of Group Development Performing Adjourning Norming Storming Return to Independence Forming Dependence/ interdependence Independence McGraw-Hill © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 12-8 Tuckman’s Five-Stage Theory Figure 12-3 cont. of Group Development Forming Storming Norming Performing “How can I “What do the Individual “How do I fit “What’s my best others expect Issues in?” role here?” perform my me to do?” role?” “Why are we fighting over “Can we agree “Can we do Group “Why are we who’s in on roles and the Issues here?” charge and work as a job properly?” who team?” does what?” McGraw-Hill © 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Influence of Intragroup Dynamics and Intergroup

Psychological Thought psyct.psychopen.eu | 2193-7281 Theoretical Analyses Influence of Intragroup Dynamics and Intergroup Relations on Authenticity in Organizational and Social Contexts: A Review of Conceptual Framework and Research Evidence Nadya Lyubomirova Mateeva*a, Plamen Loukov Dimitrovb [a] Department of Psychology, Institute of Population and Human Studies - Bulgarian Academy of Science, Sofia, Bulgaria. [b] Bulgarian Psychological Society, Sofia, Bulgaria. Abstract Despite their shared focus on influence of groups on individual, research bridging intragroup dynamics and intergroup relations as predictors of authentic and inauthentic (self-alienated) experience, behavior and interaction of individuals in organizational and social contexts is surprisingly rare. The goal of the present article is to highlight how understanding the reciprocal dynamic relationship between intragroup processes and intergroup relations offers valuable new insights into both topics and suggests new, productive avenues for psychological theory, research and practice development – particularly for understanding and improving the intragroup and intergroup relations in groups, organizations and society affecting authentic psychosocial functioning. The article discusses the complementary role of intergroup and intragroup dynamics, reviewing how intergroup relations can affect intragroup dynamics which, in turn, affects the authenticity of individual experiences, behaviors and relations with others. The paper considers the implications, theoretical and practical, of the proposed reciprocal relationships between intragroup and intergroup processes as factors influencing authentic psychosocial functioning of individuals in organizational and social settings. Keywords: group dynamics, intergroup relations, authenticity Psychological Thought, 2013, Vol. 6(2), 204±240, doi:10.5964/psyct.v6i2.78 Received: 2013-05-28. Accepted: 2013-07-01. Published (VoR): 2013-10-25. *Corresponding author at: Institute for Human Studies, Bl. -

Religion, Conflict, and Peacebuilding

SEPTEMBER 2009 Conflict is an inherent and legitimate part of social and political life, but in many places conflict turns violent, inflicting grave costs in terms of lost lives, degraded governance, and destroyed livelihoods. The costs and consequences of conflict, crisis, and state failure have become unacceptably high. Violent conflict dramatically disrupts traditional development and it can spill over FROM THE DIRECTOR borders and reduce growth and prosperity across entire regions. Religion is often viewed as a motive for conflict and has emerged as a key compo- nent in many current and past conflicts. However, religion does not always drive violence; it is also an integral factor in the peacebuilding and reconciliation process. Development assistance and programming does not always consider this link- age, nor does it fully address the complexity of the relationship between religion and conflict. As a main mobilizing force in many societies, proper engagement of religion and its leaders is crucial. This Toolkit is intended to help USAID staff and their implementing partners un- derstand the opportunities and challenges inherent to development programming in conflicts where religion is a key component. Like other guides in this series, this Toolkit discusses key issues that need to be considered when development as- sistance is provided in religious contexts and identifies lessons that been emerged from USAID’s experience implementing such programs. However compared to other types of programming, USAID experience engaging religion and religious actors to prevent conflict or build peace is modest. Thus, recognizing that there is still significantly more to be learned on this critical topic, this toolkit contains summaries of four actual USAID programs that have successfully engaged religious actors. -

The Effect of Group-Dynamics, Collaboration and Tutor Style on The

Hammar Chiriac et al. BMC Medical Education (2021) 21:379 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02814-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The effect of group-dynamics, collaboration and tutor style on the perception of profession-based stereotypes: a quasi- experimental pre- post-design on interdisciplinary tutorial groups Eva Hammar Chiriac1* , Endre Sjøvold2 and Alexandra Björnstjerna Hjelm1 Abstract Background: Group processes in inter-professional Problem-Based Learning (iPBL) groups have not yet been studied in the health-care educational context. In this paper we present findings on how group-dynamics, collaboration, and tutor style influence the perception of profession-based stereotypes of students collaborating in iPBL groups. Health-care students are trained in iPBL groups to increase their ability to collaborate with other healthcare professionals. Previous research focusing iPBL in healthcare implies that more systematic studies are desired, especially concerning the interaction between group processes and internalized professional stereotypes. The aim of this study is to investigate whether changes in group processes, collaboration, and tutor style, influence the perception of profession-based stereotypes of physician- and nursing-students. Methods: The study is a quasi-experimental pre- post-design. The participants included 30 students from five different healthcare professions, mainly medicine and nursing. Other professions were physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. The students were divided into four iPBL groups, each consisting of six to nine students and a tutor. Data were collected through systematic observation using four video-recorded tutorials. SPGR (Systematizing the Person Group Relation), a computer-supported method for direct and structured observation of behavior, was used to collect and analyze the data. -

Social Identification Processes, Group Dynamics and Behaviour Of

Volume 90 Number 870 June 2008 Social identification processes, group dynamics and the behaviour of combatants Emanuele Castano, Bernhard Leidner and Patrycja Slawuta* Emanuele Castano is Professor at the New School for Social Research, New York; Bernhard Leidner and Patrycja Slawuta are graduate students at the same institution. Abstract In this contribution, respect for international humanitarian law among combatants is considered from a social psychological perspective. According to this perspective, the social identities derived by individuals from their membership of social groups provide norms and values used by the individual to interpret events, form opinions and decide upon a course of action. We argue that group identities are particularly salient in combat situations, and that they have a profound influence on combatants’ decisions to respect or violate international humanitarian law. Violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) are carried out by individuals, but in order to understand such violations and hopefully prevent them from happening, we have to look at the determinants of such behaviour. We thus need to consider the group dimension, and more specifically the role played by social identities in framing the situation and guiding behaviour. By social identities we mean ‘‘that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a group together with the * The writing of this article was facilitated by an NSF grant to the first author and by a Fellowship for Young Scientists granted by the Gottlieb Daimler- and Karl Benz Foundation to the second author. We wish to thank Mary Hoeveler for her editing suggestions with regard to an earlier draft. -

Group Perception and Social Norms

Running header: GROUP PERCEPTION AND SOCIAL NORMS GROUP PERCEPTION AND SOCIAL NORMS Sarah Gavac University of Wisconsin-Madison Sohad Murrar University of Wisconsin-Madison Markus Brauer University of Wisconsin-Madison 11 July 2014 Word count: 14,061 Corresponding author: Sarah Gavac, Psychology Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1202 W. Johnson St., Madison, Wisconsin, 53706. E-mail: [email protected] GROUP PERCEPTION AND SOCIAL NORMS 2 SUMMARY Groups create the very basis of our society. We are, as humans, social animals. We are born into groups, learn in groups, live in groups, and work in groups. Groups can range anywhere from three people to a nation. Think of the groups you belong to. How similar are you to other members of your groups? In most cases, we tend to be similar to other members of our groups because there are standards within the group that define behavioral expectations. These standards are called social norms. Throughout this chapter, we hope to provide basic answers to some of the fundamental questions about social norms and group dynamics: What are social norms? How do social norms influence our behavior? How have social norms been studied? What are the classic experiments on social norms? What is conformity and how does it relate to social norms? When do individuals conform and why do they conform? What makes a group? How do social norms and group dynamics overlap? WHAT ARE SOCIAL NORMS? Imagine you get on an elevator. There’s no one on it, so you stand in the middle and listen to the soft music while the doors close. -

Group Dynamics and Behaviour

Universal Journal of Educational Research 7(1): 223-229, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2019.070128 Group Dynamics and Behaviour Hüseyin Gençer Maritime Higher Vocational School, Piri Reis University, Istanbul, Turkey Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Individuals are always in interaction with covered. other individuals outside, as well as in the group and with In the second chapter, intergroup dynamics were the group itself. This is why the social sciences emphasize mentioned very briefly and causes of intergroup conflict the importance of group dynamics. After the 1990’s, with were discussed. the globalization, digitalization, changing political systems, Third chapter of the study expresses the benefits of the goal or result-oriented approaches in many western groups to organizations that have also been supported by countries, new items such as cross cultural differences and recent studies in the literature. impacts, migration, social status and identity, Final chapter summarizes the concepts and subjects demographic diversities, leadership, job performance, explained in the previous chapters within the light of new motivation, dynamics in sport teams, organizational trends in group dynamics, and concludes the study with citizenship behavior (OCB), ethics, healthcare have been some suggestions. investigated in the studies on the groups and group dynamics. This study provides general information about the studies on the groups and group dynamics. 2 . Groups and Group Dynamics Keywords Groups, Group Dynamics, Intergroup A Group is a formation of at least two people who come Dynamics together in a given purpose, communicate with each other, affect each other and are dependent on each other. -

Group Dynamics, Fourth Edition Donelson R

Licensed to: 00-W3234-FM 2/10/05 8:19 AM Page ii Licensed to: Group Dynamics, Fourth Edition Donelson R. Forsyth Acquisitions Editor: Michele Sordi Permissions Editor: Sarah Harkrader Assistant Editor: Jennifer Wilkinson Production Service: G&S Book Services Editorial Assistant: Jessica Kim Text Designer: John Edeen Technology Project Manager: Erik Fortier Copy Editor: Jan Six Marketing Manager: Chris Caldeira Illustrator: G&S Book Services Marketing Assistant: Nicole Morinon Compositor: G&S Book Services Advertising Project Manager: Tami Strang Cover Designer: Denise Davidson Project Manager, Editorial Production: Emily Smith Cover Image: Blue and Yellow Squares © Art Director: Vernon Boes Royalty-Free/CORBIS Print/Media Buyer: Rebecca Cross/Karen Hunt Text and Cover Printer: Phoenix Color Corp © 2006 Thomson Wadsworth, a part of The Thomson Thomson Higher Education Corporation. Thomson, the Star logo, and Wadsworth are 10 Davis Drive trademarks used herein under license. Belmont, CA 94002-3098 USA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered Asia (including India) by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any Thomson Learning form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, 5 Shenton Way including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribu- #01-01 UIC Building tion, information storage and retrieval systems, or in any Singapore 068808 other manner—without the written permission of the publisher. Australia/New Zealand Thomson Learning Australia Printed in the United States of America 102 Dodds Street 12345670908070605 Southbank, Victoria 3006 Australia For more information about our products, contact us at: Thomson Learning Academic Resource Center Canada 1-800-423-0563 Thomson Nelson For permission to use material from this text or product, submit 1120 Birchmount Road a request online at http://www.thomsonrights.com. -

Interdisciplinary Analysis for Human Group Dynamics

Interdisciplinary Analysis for Human Group Dynamics Jesus Mario Serna1,*, Mark McCann2, Andrew Christian3, Danilo Liuzzi4, Gaetano Dato5, Justin Williams6, Lorraine Sugar7, Sina Tafazoli8 1 Université Paris 7, USPC, Recherches en Psychanalyse, Paris, France 2 University of Glasgow, UK 3 NASA Langley Research Center, USA 4 University of Milan, Milan, Italy 5 University of Trieste, Italy 6 University of North Texas, USA 7 University of Toronto, Department of Civil Engineering, Toronto, Canada 8 Princeton University, USA * [email protected] ABSTRACT There are still considerable breaches between purely qualitative and quantitative approaches in many working models for group dynamics in psychology and social sciences. We argue that an interdisciplinary approach may help bridge these gaps towards more integrative models. We ran a discussion group based on the Operative Group Model (OGM), using a complex systems approach to reinterpret its dynamics, and applied network theory as well as thematic discourse analysis (DA). Finally, we consider the potential advantages of performing an acoustic analysis on the audio recordings from the group sessions. To our knowledge, this integrative approach has never been applied in the context of an OGM. In this study we provide two main levels of analysis: the participant’s personal and group experience, and the experimentation and analysis methods’ aspect. For the former, we gather data from group theory in psychology, psychoanalysis, the OGM, and the participants’ feedback. We then use DA and a bipartite graph identifying weighted “thematic nodes” as a research framework. Finally we explore possible ways to incorporate an acoustic analysis, notably implementing a Hidden Markov Model (HMM). -

What Can Problem-Based Learning Do for Psychology?

Ask Not Only ‘What Can Problem-Based Learning Do For Psychology?’ But ‘What Can Psychology Do For Problem-Based Learning?’ A Review of The Relevance of Problem-Based Learning For Psychology Teaching and Research Sally Wiggins, Eva Hammar Chiriac, Gunvor Larsson Abbad, Regina Pauli and Marcia Worell Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Sally Wiggins, Eva Hammar Chiriac, Gunvor Larsson Abbad, Regina Pauli and Marcia Worell, Ask Not Only ‘What Can Problem-Based Learning Do For Psychology?’ But ‘What Can Psychology Do For Problem-Based Learning?’ A Review of The Relevance of Problem-Based Learning For Psychology Teaching and Research, 2016, Psychology Learning & Teaching, (15), 2, 136-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1475725716643270 Copyright: SAGE Publications (UK and US) http://www.uk.sagepub.com/home.nav Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-129810 Ask not only ‘what can PBL do for psychology?’ but ‘what can psychology do for PBL?’ A review of the relevance of problem-based learning for psychology teaching and research Sally Wiggins, Eva Hammar Chiriac, Gunvor Larsson Abbad, Regina Pauli, Marcia Worrell. Abstract Problem-based learning (PBL) is an internationally recognised pedagogical approach that is implemented within a number of disciplines. The relevance and uptake of PBL in psychology has to date, however, received very limited attention. The aim of this paper is therefore to review published accounts on how PBL is being used to deliver psychology curricula in higher education and to highlight psychological research that offers practical strategies for PBL theory and practice. -

The Large Group: Dynamics, Social Implications and Therapeutic Value Haim Weinberg and Daniel J

23 The Large Group: Dynamics, Social Implications and Therapeutic Value Haim Weinberg and Daniel J. N. Weishut The Large Group: Typical Dynamics For many group therapists who are used to the traditional small group, the large group format is unknown and confusing. When coming to a conference that includes a large group, some participants ignore it as if it never existed in the conference schedule or deliberately avoid it and skip its meetings. Others come once, feel over‑ whelmed, frustrated and perplexed, and vow that they will never come again. Still others come from time to time, wondering about the nature of this “strange beast,” waiting for the features of the small group to appear. Yet some group practitioners become hooked to the large group, attending year after year, feeling that something important is happening there, and even finding that the large group becomes the highlight of the conference for them. We would like to make the large group more “user‑friendly” by explaining its dynamics and pointing out its typical processes, and hope that this will assist potential participants in their learning process. In recent years the large group has regained attention as an experiential or learning group in order to understand societal processes. When referring to “the large group” (LG) in this paper, we relate to an experiential group with membership anything above 30–35, led in an unstructured way, usually from a psychodynamic perspective. This kind of LG can be found in psychological and especially group psychotherapy conferences.1 We “utilize the large group experience as a laboratory in which to study large group processes, both conscious and unconscious, as a way of understanding their impact and influence upon social, organizational and systemic thinking, feelings and actions” (Weinberg and Schneider, 2003: p.