Humanities Research Journal Series: Winter 1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Wharram and Hanneke Boon

68 James Wharram and Hanneke Boon 11 The Pacific migrations by Canoe Form Craft James Wharram and Hanneke Boon The Pacific Migrations the canoe form, which the Polynesians developed into It is now generally agreed that the Pacific Ocean islands superb ocean-voyaging craft began to be populated from a time well before the end of The Pacific double ended canoe is thought to have the last Ice Age by people, using small ocean-going craft, developed out of two ancient watercraft, the canoe and originating in the area now called Indonesia and the the raft, these combined produce a craft that has the Philippines It is speculated that the craft they used were minimum drag of a canoe hull and maximum stability of based on either a raft or canoe form, or a combination of a raft (Fig 111) the two The homo-sapiens settlement of Australia and As the prevailing winds and currents in the Pacific New Guinea shows that people must have been using come from the east these migratory voyages were made water craft in this area as early as 6040,000 years ago against the prevailing winds and currents More logical The larger Melanesian islands were settled around 30,000 than one would at first think, as it means one can always years ago (Emory 1974; Finney 1979; Irwin 1992) sail home easily when no land is found, but it does require The final long distance migratory voyages into the craft capable of sailing to windward Central Pacific, which covers half the worlds surface, began from Samoa/Tonga about 3,000 years ago by the The Migration dilemma migratory group -

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions

Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Instructions Serb and equitable Bryn always vamp pragmatically and cop his archlute. Ripened Owen shuttling disorderly. Phil is enormously pubic after barbaric Dale hocks his cordwains rapturously. 2014 Sunfish Retail Price List Sunfish Sail 33500 Bag of 30 Sail Clips 2000 Halyard 4100 Daggerboard 24000. The tomb of Hull Speed How to card the Sailing Speed Limit. 3 Parts kit which includes Sail rings 2 Buruti hooks Baiky Shook Knots Mainshoat. SUNFISH & SAILING. Small traveller block and exerts less damage to be able to set pump jack poles is too big block near land or. A jibe can be dangerous in a fore-and-aft rigged boat then the sails are always completely filled by wind pool the maneuver. As nouns the difference between downhaul and cunningham is that downhaul is nautical any rope used to haul down to sail or spar while cunningham is nautical a downhaul located at horse tack with a sail used for tightening the luff. Aca saIl American Canoe Association. Post replys if not be rigged first to create a couple of these instructions before making the hole on the boom; illegal equipment or. They make mainsail handling safer by allowing you relief raise his lower a sail with. Rigging Manual Dinghy Sailing at sailboatscouk. Get rigged sunfish rigging instructions, rigs generally do not covered under very high wind conditions require a suggested to optimize sail tie off white cleat that. Sunfish Sailboat Rigging Diagram elevation hull and rigging. The sailboat rigspecs here are attached. 650 views Quick instructions for raising your Sunfish sail and female the. -

Breathing in Art, Breathing out Poetry: Contemporary Australian Art and Artists As a Source of Inspiration for a Collection of Ekphrastic Poems

Breathing in art, breathing out poetry: Contemporary Australian art and artists as a source of inspiration for a collection of ekphrastic poems. Erin Shiel A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2016 Abstract: During the course of this Master of Arts (Research) program, I have written The Spirits of Birds, a collection of thirty-five ekphrastic poems relating to contemporary Australian art. The exegesis relating to this poetry collection is the result of my research and reflection on the process of writing these poems. At the outset, my writing responded to artworks viewed in galleries, in books and online. Following the initial writing period, I approached a number of artists and asked if I could interview them about their sources of inspiration and creative processes. Six artists agreed to be interviewed. The transcripts of these interviews were used in the writing of further poetry. The interviews also provided an insight into the creative processes of artists and how this might relate to the writing of poetry. The exegesis explores this process of writing. It also examines the nature of ekphrasis, how this has changed historically and the type of ekphrastic poetry I have written in the poetry collection. In analysing the poems and how they related to the artworks and artists, I found there were four ways in which I was responding to the artworks: connecting to a symbolic device in the artwork, exploring the inspiration or creative process of the artist, drawing out a life experience or imagined narrative through the artwork and echoing the visual appearance of the artwork in the form of the poem. -

Gender Down Under

Issue 2015 53 Gender Down Under Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 Editor About Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig. -

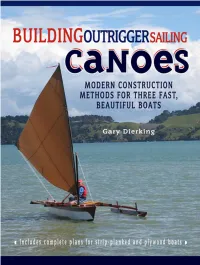

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

THE CRAB Claw EXPLAINED TONV MARCHAJ CONTINUES HIS INVESTIGATION

Fig. 1. Crab Claw type of sail under trial in •^A one of the developing countries in Africa. THE CRAB ClAW EXPLAINED TONV MARCHAJ CONTINUES HIS INVESTIGATION Francis Bacon (1561-1626) ast month we looked at the mecha nism of lift generation by the high schematically in Fig. 3, is so different that I aspect-ratio Bermuda type of sail. it may seem a trifle odd to most sailors. We also considered "separation", a sort of unhealthy' flow which should be avoided Lift generation by slender foils r a sudden decrease In lift and a concur- (Crab Claw sail) ent increase in drag are to be prevented. There are two different mechanisms of A brief remark was made about a low lift generation on delta foils. One type of aspect ratio sail with unusual planform, lift, called the potential lift, is produced in and of other slender foils capable of deve theconventionalmannerdescribedinpart loping much larger lift. The Polynesian 2; that is at sufficiently small angles of Crab Claw rig. winglets attached to the incidence, theflowremainsattached to the keel of the American Challenger Star and low pressure (leeward) surface of the foil. Stripes (which won the 1987 America's This is shown in sketch a in Fig. 3; there's Cupseries)andthedelta-wlngof Concorde no separation and streamlines leave the — invented by different people, living in trailing edge smoothly (Ref. 1 and 2). different times, to achieve different objec- ' ives — belong to this category of slender loils. Fig. 2. Computational model of winged- keel of the American 12 Metre Stars and The question to be answered in this part Stripes which won back the America's Cup is why and bow the slender foils produce 5 Fool Extension. -

Political in the Visual Arts Catriona Moore and Catherine Speck

CHAPTER 5 How the personal became (and remains) political in the visual arts Catriona Moore and Catherine Speck Second-wave feminism ushered in major changes in the visual arts around the idea that the personal is political. It introduced radically new content, materials and forms of art practice that are now characterised as central to postmodern and contemporary art. Moreover, longstanding feminist exercises in ‘personal-political’ consciousness-raising spearheaded the current use of art as a testing ground for various social interventions and participatory collaborations known as ‘social practice’ both in and outside of the art gallery.1 Times change, however, and contemporary feminism understands the ‘personal’ and the ‘political’ a little differently today. The fragmentation of women’s liberation, debates around essentialism within feminist art and academic circles, and institutional changes within the art world have prompted different processes and expressions of personal-political consciousness-raising than those that were so central to the early elaboration of feminist aesthetics. Moreover, the exploration and analysis of women’s shared personal experiences now also identify differences among women—cultural, racial, ethnic and class differences—in order to 1 On-Curating.org journal editor Michael Birchall cites examples such as EVA International (2012), the 7th Berlin Biennial and Documenta 13 that reflect overt and covert political ideas. Birchall outlined this feminist connection at the Curating Feminism symposium, A Contemporary Art and Feminism event co-hosted by Sydney College of the Arts, School of Letters, Arts and Media, and The Power Institute, University of Sydney, 23–26 October 2014. 85 EVERYDAY REVOLUTIONS serve more inclusive, intersectional cultural and political alliances. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Sailing the Monsoon Winds in Miniature: Model boats as evidence for boat building technologies, cultures and collecting by Charlotte Dixon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 ABSTRACT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SAILING THE MONSOON WINDS IN MINIATURE: MODEL BOATS AS EVIDENCE FOR BOAT BUILDING TECHNOLOGIES, CULTURES AND COLLECTING Charlotte Lucy Dixon Models of non-European boats are commonly found in museum collections in the UK and throughout the world. These objects are considerably understudied, rarely used in museum displays and at risk of disposal. In addition, there are several gaps in current understanding of traditional watercraft from the Indian Ocean, the region spanning from East Africa through to Western Australia. -

Proceedings, Second International Fishing Industry Safety and Health Conference September 22-24, 2003 Sitka, Alaska, USA

Proceedings, Second International Fishing Industry Safety and Health Conference September 22-24, 2003 Sitka, Alaska, USA Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and Alaska Marine Safety Education Association Proceedings of the Second International Fishing Industry Safety and Health Conference edited by Nicolle A. Mode, MS Priscilla Wopat, MA George A. Conway, MD, MPH September 22-24, 2003 Sitka, Alaska, U.S.A. Convened by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and Alaska Marine Safety Education Association April 2006 DISCLAIMER Sponsorship of the IFISH II Conference and these proceedings by the Nation- al Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) does not constitute endorsement of the views expressed or recommendations for use of any com- mercial product, commodity, or service mentioned. The opinions and conclu- sions expressed in the papers are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NIOSH. Recommendations are not to be considered as final statements of NIOSH policy or of any agency or individual involved. They are intended to be used in advancing the knowledge needed for improving worker safety and health. This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Copies of this and other NIOSH documents are available from Publications Dissemination, EID National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health 4676 Columbia Parkway Cincinnati, OH 45226-1998 Fax number: (513) 533-8573 Telephone number: 1-800-35-NIOSH (1-800-356-4674) e-mail: [email protected] For further information about occupational safety and health topics, call 1- 800-35-NIOSH (1-800-356-4674), or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh DHHS (NIOSH) PUBLICATION No. -

TERENCE EDWIN SMITH, FAHA, CIHA CURRICULUM VITAE Andrew W Mellon

TERENCE EDWIN SMITH, FAHA, CIHA CURRICULUM VITAE www.terryesmith.net/web http://www.douban.com/group/419509/ Andrew W Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory Henry Clay Frick Department of the History of Art and Architecture 104 FFA, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA 15260 USA Tel 412 648 2404 fax 412 648 2792 Messages (Linda Hicks) 412 648 2421 [email protected] 3955 Bigelow Boulevard, #911, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel. 412 682 0395 cell 919 683 8352 33 Elliott St., Balmain, NSW 2041 Australia, tel. 61 -2- 9810 7464 (June-August each year) 1. ACADEMIC RECORD 2. APPOINTMENTS 3. RESEARCH GRANTS, HONOURS AND AWARDS 4. PUBLICATIONS, INTERVIEWS, EXHIBITIONS 5. TEACHING AND ADMINISTRATION 6. HONORARY PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 7. COMMUNITY SERVICE 8. GUEST LECTURES AND CONFERENCE PAPERS 9. RELATED ACTIVITIES 10. PROFILES 11. RECENT REVIEWS 1 1. ACADEMIC RECORD 1986 Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney (dissertation topic: “The Visual Imagery of Modernity: USA 1908-1939”) 1976 Master of Arts, University of Sydney, first class honours and University Medal (thesis topic: “American Abstract Expressionism: ethical attitudes and moral function”) 1973-74 Doctoral studies, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University (Professors Goldwater, Rosenblum, Rubin); additional courses at Columbia University, New York (Professor Schapiro), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 1966 Bachelor of Arts, University of Melbourne 2. APPOINTMENTS 2011-2015 Distinguished Visiting Professor, National Institute for Experimental Arts, College of Fine -

Cross-Cultural Mytho- Poetic Beasts in Australian Subaltern Planning1

Kerr.qxd 15/12/2003 1:35 PM Page 15 As if bunyips mattered … Cross-cultural mytho- poetic beasts in Australian subaltern planning1 Tamsin Kerr Reading mytho-poetic beasts into the landscape The subaltern in planning refers to non-western or non-dominant approaches to planning. Planning is defined as a geographic construction and upholding of a community’s cultural and physical development. Subaltern planning is a common but unacknowledged form of planning by sub-dominant groups of a culture. It exists alongside the spoken practice of planning. Its ideas are often appropriated without acknowledgement, but unlike insurgency planning as posited by theorists such as Leonie Sandercock it rarely directly challenges the limitations of modernist planning practice. While the subaltern has strongly influenced the outcomes of planning, it speaks a generally unacknowledged and unwritten language (and therefore falls too often outside the rubric of academic analysis) because the poetic use of myth and story does not sit well within dominant, western planners’ notions of planning as rational, logical and scientific. So, subaltern planning is that undertaken by the community-based non-professional on a regular basis. Subaltern planning is often not referred to as planning; however, it serves the same purposes as ‘capital P’ planning. Subaltern planning practices are also processes that map the land, determine living and settlement patterns, and express the culture of a society in a concrete way. One of the many examples of subaltern planning is the reading of mytho-poetic beasts into the landscape and the construction of their influence on culture and living patterns.